Download the Policy Brief (PDF)

INTRODUCTION

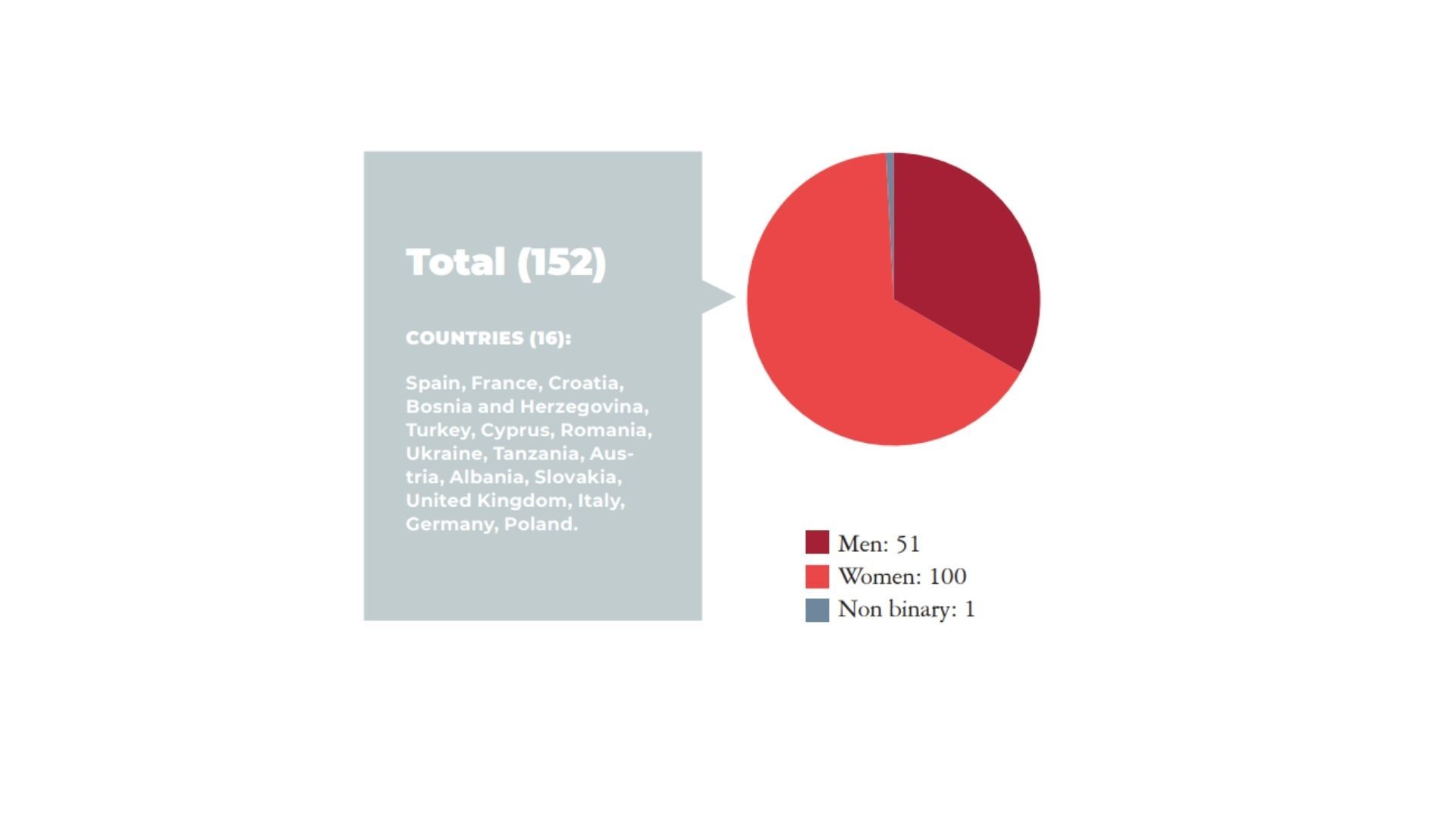

This document presents the outcomes of the most relevant discussions that took place within the framework of the project Youth and Memory Activism (You&Me) developed throughout 2021 and 2022, including the results of an online survey promoted by all partner organisations. It also proposes some recommendations in a bid to involve young people in the field of remembrance from a transnational perspective, aiming to develop a tool that could be applied internationally.

The project aimed to boost the relevance of youth in collective remembrance and memory politics, by stimulating exchanges of know-how and best practices in three European countries: Spain, which had not properly addressed its turbulent past until recently, when the “grandchildren generation” finally started dealing with the consequences of the Spanish Civil War and the Francoist dictatorship; Cyprus, which remains divided since Turkey occupied 35% of the island in 1974, and today young people either don’t care about or have populist beliefs related to local history; and Bosnia-Herzegovina, which is still struggling with its transitional justice and reconciliation processes following the events of the 1990s, where the youth population is immersed in conflicting and contradicting narratives of the past.

You&Me raised shared questions about the troubled pasts in the three countries, which launched interesting debates during the international workshops that took place in Barcelona, Nicosia and Sarajevo. The goal of the youth exchanges was, on the one hand, to learn from other countries’ difficult pasts and explore how these are addressed today, and on the other, to question the tools that would encourage young people to become players in public memory.

Barcelona Workshop, April 2022 | EUROM

HOW TO ENGAGE YOUNG PEOPLE IN MEMORIAL PROCESSES

The young participants of the project activities had in common that they had not experienced any of the traumatic events that shaped the recent history of their respective countries (neither the Spanish Civil War nor the Franco dictatorship; the 1990s Bosnian War, or the occupation in Cyprus). However, at the same time, they felt constantly exposed to the memories of these events, whether through conversations with family or friends, in the media or at school, through movies, novels, songs, pictures, monuments, memorial parks or museums.

These memories to which we are exposed on a daily basis not only affect our perception of past events but also change our relationship with the community to which we belong and our way of constructing an identity, that is, our way of perceiving ourselves.

Remembering is a collective process in which individuals, civil society organisations and institutions interact by building common meanings and symbols. Every act of memory is a process of interpreting the past that inevitably builds relationships and social identities. Yet memory policies can often be deliberately non-existent in order to silence an uncomfortable past or to omit some parts of history. In some cases, they also promote certain narratives by trying to manipulate the visions of the past with a clear political purpose.

As young people who have experienced the consequences of this treatment of the past, we are convinced that until these narratives are problematised, it will not be possible to move towards a fairer and more democratic society.

We believe that taking into account youth’s perspective in memory processes is essential to cast doubt on the hegemonic versions prevailing in our social order. The outlook of people who have not experienced problematic events can help to call into question the versions of the past presented by certain narratives, and can inspire new understandings and meanings, offering a more open and mobile view of memory

Most of the project participants aimed to contest their governments’ narratives or to shift the perspective presented by the authorities. Consequently, they think that it is when memorial initiatives come from civil society that youth groups or individuals can be further motivated and their actions can have a bigger impact.

RECOMMENDATIONS

With this in mind, the project participants developed a list of recommendations and pointers to serve as guidance for institutions, civil society organisations or grassroots movements that would be interested in carrying out a memorialisation process.

1. Actively include younger generations in post-conflict processes

After a conflict, the mindset of the population is resentful, and it is very difficult to find the will for conciliation. Young people, as people who often have not experienced conflicts first-hand, hold a position that can be highly beneficial in resolving past or latent conflicts. Not surprisingly, several theorists have focused on the importance of the third generation of a conflict-ridden society in order to complete peace processes.

Thus, past events can be approached without forgetting them and without seeking revenge and, ultimately, this coming together can create a new common narrative. Since political power tends to use conflictual portrayals of the past to their own advantage, it is more likely that major social changes will come from the population than from government. Here, youth groups can play an important role in creating spaces that allow people from different backgrounds, ideologies and origins to meet and talk, addressing conflict resolution through respect and dialogue. That is why it

is so important to consider them as equal partners.

Sarajevo (left) and Nicosia workshops.

2. Promote participatory, pluralistic and inclusive projects

The consequences of a conflict often leave one or more groups of people voiceless in the public sphere. It is important to be aware of the barriers that prevent some people from taking part in reconstruction and memory processes, and to do as much as possible to engage them. In order to reverse privileges inherited in the past, remembrance policies should consider and give way to “other” memories that have been silenced (minorities, race, gender, functional diversity, sexual diversity, etc.). Societies are not homogeneous. It is essential to take into account their diversity

during memory processes in order to build a pluralistic discourse. Peace and, later, memory processes must be comprehensive and multidimensional; meaning that action must be taken from the local, regional and global spheres, as well as through public and private initiatives.

3. Expand historical memory perspectives beyond the victims

In order to avoid dualistic versions of history, it can be helpful to set aside actions of remembrance that focus exclusively on the figure of the victim. The suffering of the victims is a key element of this kind of rhetoric and it plays a central role in the places of remembrance, although the definition of who the victim is may be different depending on the social, ideological, and even ethnic position of the person expressing their opinion. Widening the focus of memory from the victims to the recovery of historical experiences and transformative projects can prevent the most

belligerent versions of history and contribute to the present with a broad mindset.

4. Develop memory policies to support prevention and peace-building

Conflicts that have not been well resolved — and where belligerent narratives persist — are dormant conflicts, which can be relaunched at any time. For this reason, the best long-term memory policy is one of prevention, that guarantees strong social cohesion and peaceful coexistence among members of the same community. This will prevent biased versions of memory from occurring in the future, or reversing historical discourses for political purposes. We must provide citizens with tools for healing — and this means psychological assistance after a war — but also and

especially, we must create spaces for coexistence, tools for mediation, and a political willingness for dialogue, which means investing less in the military and more in education and peace-building policies.

5. Review formal education to include debates on memory

It is crucial to review educational policies and to encourage critical thinking in the teaching of history. Students and society as a whole must know how to distinguish history (a set of events) from memory (interpretations of these events), so they will be able to question hegemonic narratives: Why do we remember in this way? Are there other possible versions of the past? What interests run through every historical discourse?

6. Promote scientific research to avoid denialism

Just as it is important to question the learning of history, we must also provide ourselves with the scientific tools to conduct careful, non-biased research into history. For example, creating or supporting research centres that provide accurate and verified information about past events, to avoid versions of denialism.

Visiting the Exile Memorial Museum at La Jonquera (left) and Sarajevo workshop (right).

CONCLUSIONS

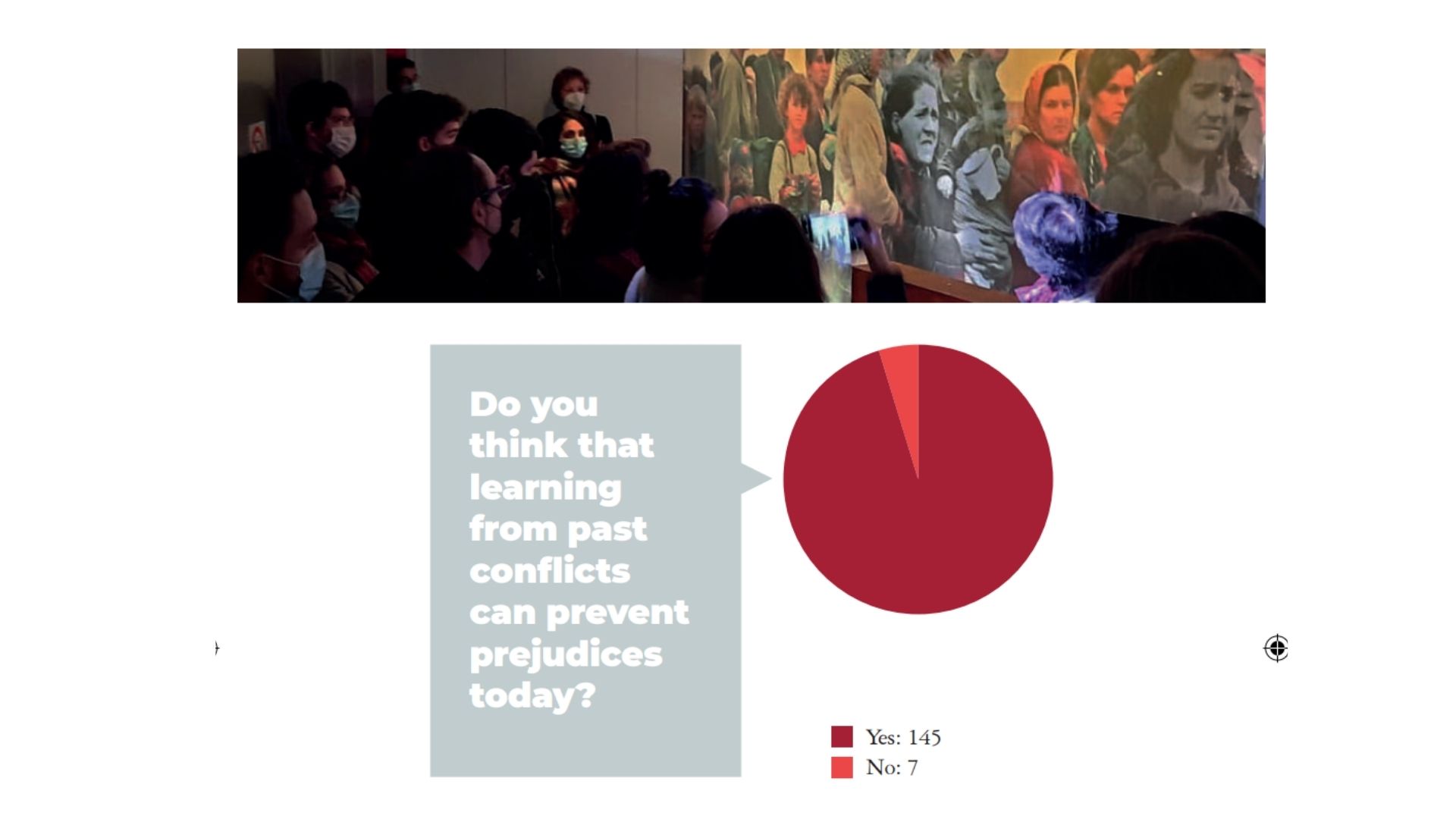

These conclusions are based on the discussions developed during the project exchanges and on the answers and comments made by the respondents to the online survey (aged 16-30). The most consensual answer — more than 90% — was that addressing the past is relevant for the future, in the sense that taking into account past conflicts can prevent prejudices and foster tolerance. As one of the reasons why it is important to address the past, it was argued that “by dealing with a past conflict and actively discussing it, we can see both sides of the story and understand the absurdity of violence and the damage it is doing in our current society, so we can then move forward.” Some other answers underlined the fact that “we are still acting with the reflexes from the past,” so having open discussions on history and memory would contribute to more tolerant behaviours.

On the other hand, when it comes to the narratives that currently prevail, the opinions were much more controversial, and a lot of young people — more than 80% — do not, or sometimes do not, feel comfortable with them. They pointed out the inability to listen to the other side of the story and the use of those narratives for propagandistic purposes by some politicians: “I am not comfortable with the dominant narrative in my country on historical debates. Most of ‘our’ history is being taught by creating ‘others’ and adopting a heroic and innocent representation of the majority identities,” answered one youngster. And another one expressed: “I am not comfortable because some debates and opinions just keep getting on my nerves, people generalise and don’t want to listen.”

The awareness of the current historical debates in the respondents’ countries was perceived as quite high, as was the knowledge about remembrance concepts such as historical memory or collective memory. Most of the respondents identify collective memory as the way a community remembers its own past, and some of them also linked it to concepts such as justice, understanding of history, and the responsibility to remember.

Sarajevo workshop (upper and bottom left), and visit to the Exile Memorial Museum at La Jonquera (bottom right).

When asked about what local, national or European institutions should do in this regard, participants highlighted the need for more public funds; more initiatives to promote remembrance; the relevance of having educational programmes to promote a reflection of the past; and to involve young people in remembrance politics, considering them as valid interlocutors in the development of historical narratives and the generation of memorial processes. Some answers also called attention to states’ responsibility when it comes to preventing conflicts, that is, avoiding the use of

history to serve ideologies of hate.

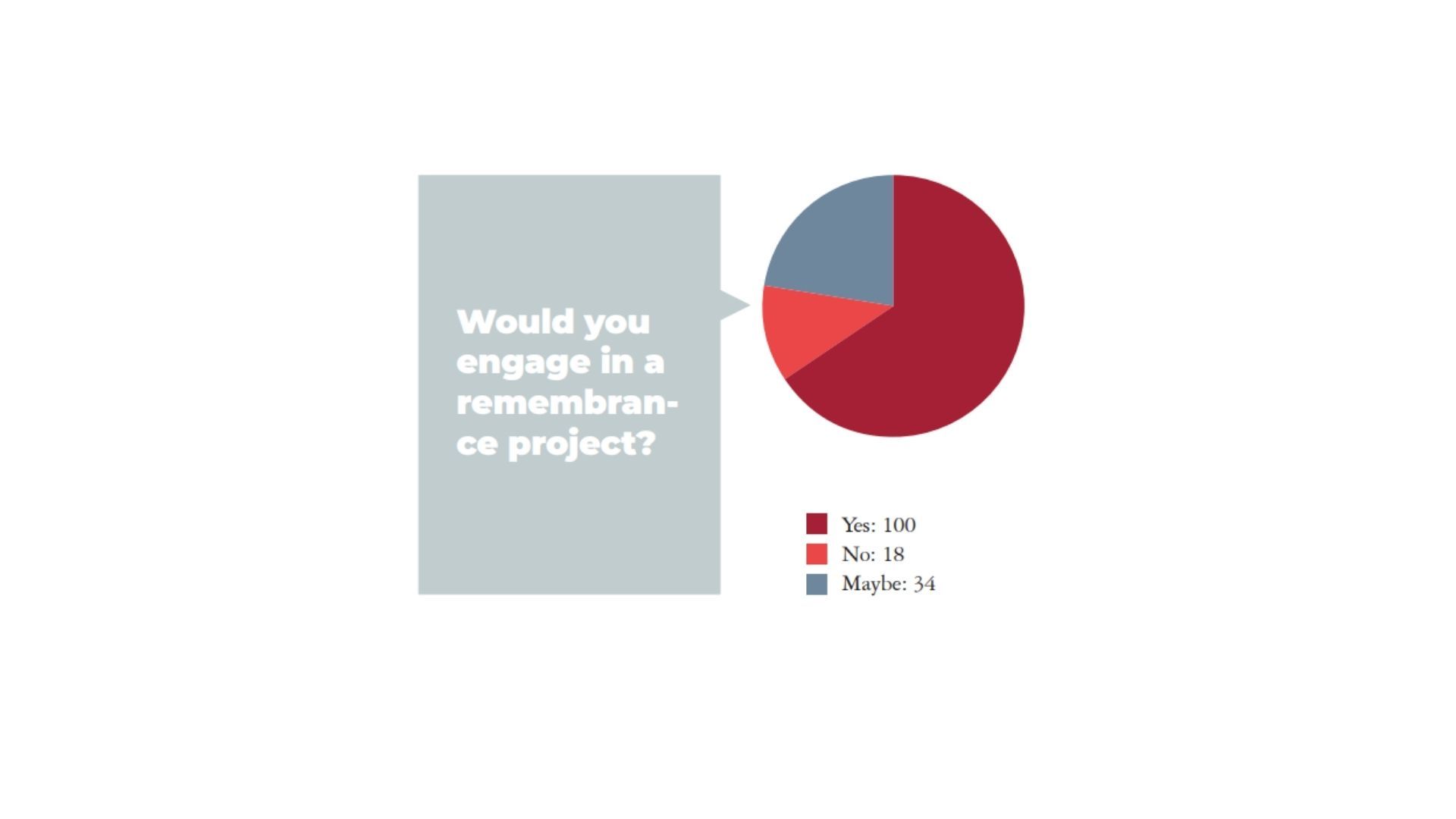

Finally, the most hopeful data obtained in the survey is probably that two out of three youngsters would engage in a remembrance project. According to the majority of survey respondents, they would want their remembrance project to fulfil the following purposes.

• Allow different narratives, historical events, and points of view to be represented.

• Promote dialogue between different memorial narratives.

• Treat the past with empathy, commitment and awareness in order to build projects for the present and the future.

• Create inclusion and increase the quality of communication among conflicting groups.

• Allow space for critical thinking.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Contents based on the contributions made by all participants in the project You&Me

Text written and edited by: Àngel Reguera, Fernanda Zanuzzi, Laura Molinos Solà, Núria Sala Ventura and Oriol López Badell

Proofreading: Subtil. Comunicació i Accessibilitat SCP.

Cover illustration: Nadira Ćurulija

Graphic design: Carles Mestre