- This multimedia campaign is part of our efforts to make the facts of the Holocaust respected and to avoid Holocaust distortion.

Together with many other stories of Jews settled in Spain in the begining of the 20th century, the memories of Werner Barasch and Jacob Neeman reveal the darks and lights of Francoism and its relation to Nazism during the years of the Second World War

Werner Barasch (Breslau, Poland, 1919 – Santa Cruz, USA, 2008) and Jacob Neeman (Sieradz, Poland, 1884 – Hadera, Israel, 1982) survived the Holocaust crossing the Pyrenees. Before gaining freedom they were imprisoned by Spanish authorities at La Model prison in Barcelona and sent to the Francoist concentration camp of Miranda de Ebro. Barasch was detained by the Spanish police at the Catalan-French border and accused of clandestine border crossing and smuggling money. Neeman would be arrested by the secret police in his hotel room in Barcelona.

In the book “Fugitives”, Werner Barasch reminds the prison La Model as a hot and crowded place, with over 10,000 inmates at that time. Jacob Neeman arrived in Barcelona in August 1942 after escaping the Nazi assault against foreign Jews living in the south of France. His wife was arrested and deported to the Auschwitz extermination camp. Neeman left Aulus-les-Bains (Ariège) and went to Andorra from where he managed to reach Barcelona. From La Model prison he was transferred to the Miranda de Ebro (Burgos) concentration camp. His story is now being recovered by the historian Josep Calvet.

Not all Jews who crossed the Pyrenees by that time had the same fate. Some were returned to France by the Francoist authorities and later deported to Nazi camps. Others were detained at the border and handed over directly to Nazi authorities. Together with other stories of many Jews settled in Spain, these memories reveal the darks and lights of Francoism and its relation to Nazism during the years of the Second World War.

Related content: Online exhibition “Barcelona, a shelter for the Jews“

Marianne Hirsch and Géraldine Schwarz represent two generations of Holocaust-related families. Both are among the main voices on memory (and post-memory) studies. They recently collaborated with the EUROM, both in the Observing Memories magazine and in the annual meeting Taking Stock of European policies on memory.

Later on, she realized that her parents’ memory of the Second World War was more powerful than her own childhood memories, so she began to write and investigate the concept of post-memory. “In fact, what they handed out for me was a memory of Europe, a Europe that was their horizon of culture, of cosmopolitanism, of cohabitation, of freedom”, she says.

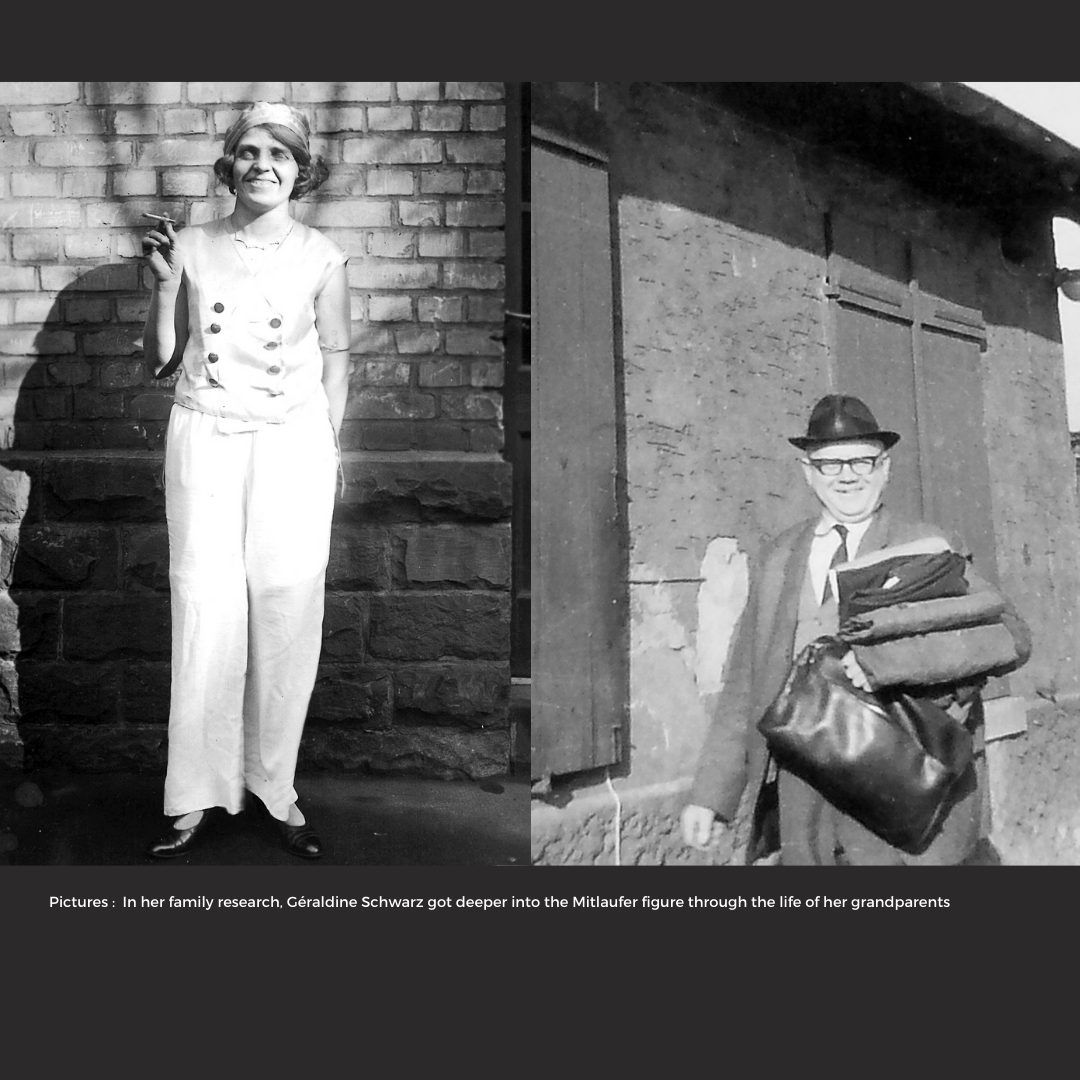

Géraldine Schwarz’s grandfather Carl Schwarz was a member of the Nazi Party in the 1930s. Not really an active member, she explains in her book, but a “mitläufer” – a bystander or an implicated – one following the current. She never met him but found his story in letters, pictures and documentation.