Memory conflicts on social media: Twitter data analysis

Fifth report – First semester, 2021

Texts by Celeste Muñoz Martínez | Graphs by Mariluz Congosto

The relevance of the ‘online memories’ project and some theoretical considerations

In 2018, the European Observatory on Memories (EUROM) decided to launch a new line of research in order to fill a real and worrying gap in the study of memory practices in our society. This barely explored space is the world of ‘social networks’. Rather than being classified as an emerging phenomenon, these should be considered a consolidated reality. A high percentage of the world’s population has digital identities[1] through which they socialise, access information, mobilise and interact with an endless number of realities (and unrealities). Since the rise of social networks in the early 21st century, there has been a proliferation of web spaces, applications and platforms (from Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn to other more current ones such as Tik-Tok, Tumblr and Snapchat, among others), whose capacity to generate information and create links between people and groups exceeds the parameters known prior to their appearance. For this reason, it is unsurprising that the large agencies dedicated to digital marketing (for commercial and political purposes, among others) have focused a large part of their penetration strategies on these spaces. Equally foreseeable is the multiplication of social studies that analyse both the Internet’s information circuits and the consolidation of digital communities – which express existing social diversity by adding new complexities. A quick GoogleScholar search shows that at least 16,000 items of content have been created since 2017 that deal exclusively with the role of Twitter in political, sporting, educational, economic and current affairs processes. Among the most analysed topics are the digital strategies of the ‘new right’ (Trumpism, Bolsonaro, Euroscepticism, etc.);[2] more general political analyses (electoral behaviour, Brexit, etc.);[3] the rise of digital activism (Black Lives Matter, feminist wave, etc.);[4] digital narratives on the COVID19 pandemic and emergencies;[5] and the impact of hate speech.[6]

The centrality of these platforms in contemporary life is total and should be dealt with exhaustively because of their enormous capacity to generate political polarisation, flows of opinion and events as catalysts of the tensions in their context. However, disciplines such as history or memory studies have not sufficiently addressed their potential as sources of the present and the past. The Internet should not be treated solely as a journalistic or sociological source. Networks participate in the creation of events; they are not merely a medium through which such events crystallise. So they should be treated as sources for historical analysis and as spaces of collective memory. The absence of studies that take this position on networks is not total, but it is noticeable, with the exception of certain recent research which enables us to construct a theoretical yet still insufficient framework. In this regard, it is worth mentioning the text by Adriana Araceli Figueroa Muñoz Ledo entitled Pensar los lugares de memoria: el uso del hashtag en Twitter (Thinking places of memory: the use of the hashtag on Twitter, 2020), in which she argues that hashtags themselves currently represent spaces of memory that in the past had a greater materiality, generating living narratives around this common element. She sees the hashtag as an archive for memory that does not just host it but also participates in its creation:

To think of the hashtag on Twitter as a possible space for and location of the construction of memory, where ‘ordinary’ people keep an event alive that was ‘officially’ constructed in another way. This is likewise an exercise in considering the opportunities provided by socio-digital networks to collectively elaborate a discourse on memory and to observe how it is interwoven with other events.

Her study analyses how these more or less static tags have been filled with content by sampling various hashtags relating to the anniversaries of the fateful earthquake in Ayotzinapa (Mexico). In part, our study shares Figueroa’s theoretical premise since, unlike other studies on digital memory that focus on specific accounts, the online memories project takes tags as the analytical reference framework to detect the diversity of memory discourses that are produced around an event or commemoration. As the author rightly points out (drawing on the studies of Maurice Halbwachs and Pierre Nora):

Social groups create ‘places of memory’, i.e. spaces where they deposit their accepted accounts of how some event occurred and which elements concerning it are to be emphasised. (…) These places of memory are those where ‘memory operates’. That is to say, they are not the physical spaces where past events occurred, but the spaces that trigger/stimulate thinking about the past or spaces that are not necessarily physical (…).[7]

Based on this reflection, the Internet could and should also be redefined as a place of memory because, like public space, networks are not a neutral place either. They escape the control of hegemonic or official discourses, while also acting as a vehicle for them.[8] In short, they are a space of conflict with enormous potential. We have seen how after the death of George Floyd the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter identified the rage, creating a community that redefined discourses on colonial and slave memory, finally turning monuments to Columbus (among others) into the focus of protests. Networks have also been key to memories of the pandemic that swept the world in the year 2020. Likewise, after terrorist attacks, they become a space for tributes. The examples are numerous.

The difficulty for the emergence of these studies is undoubtedly the low penetration of digital methodologies applied to memory and history studies. Undoubtedly, the archives of the future for the study of the contemporary period will not only consist of institutional records, interviews and press. Current history is also created on the Internet and networks. To be clear, it will be difficult to explain Brexit, the rise of new populisms, new ideological currents or other social conflicts without processing the information generated by the participating actors and observers in their profiles. The web is an autonomous medium that generates its own narratives, acting as an engine for change, not merely a space that reproduces what occurs outside itself. The future of the discipline must take the teaching of these methodologies in faculties seriously. They must champion multidisciplinarity, not just with the other social sciences but also with computer studies and digital communication. The online memories project was a joint project with Dr Mariluz Congosto,[9] who has processed the Internet data into graphs and content analysis tables. Without such collaboration, scientific and methodological innovation projects such as this would not be possible. The extensive work of the History, Memory and Digital Society Group (HISMEDI) led by Dr Matilde Eiroa (Universidad Carlos III) should also be recognised. Its members have published pioneering studies for the establishment of digital history methodologies.[10] HISMEDI has likewise run two R&D projects on digital memories on the web, having undertaken the most comprehensive work on the subject.[11]

Lastly, these analyses would lack sufficient rigour without close collaboration with the field of sociology. Networks, apparently, are a chaotic space of relationships, connections and communities that generate millions of data per second, but which can be ordered on the basis of patterns and population strata. It is relevant to have in-depth knowledge of the gender or social class gap in these media, as well as to understand users’ digital behaviour. For example, sociology provides us with valuable data for understanding so-called ‘filter bubbles’ – the network algorithm that directs our content towards our interests and allows users to be cut off from information that does not agree with their points of view so as to keep them isolated in ideological and cultural bubbles.[12] As it does for the ‘echo chamber’, an expression explaining how through the previous phenomenon we perceive amplified confirmations or facts occurring on the web. The information is repeated by people in the affinity group until it acquires an extreme variety that makes it difficult to critically discuss or truly situate the phenomenon. These two sociological variables are key to understanding what we will call in this text the ‘Twitter bubble’. In other words, what happens on the web is a real construction or, rather, a real memory; but if this is not situated in sociological and digital behavioural terms, it can facilitate distorted readings of its true reach. With these theoretical premises in mind, in the following section we will try and update the sociological data we have collected in previous reports.

Data on the sociological profile

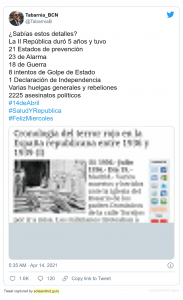

Social networks with greatest number of active users worldwide in January 2021 (in millions)

In usage terms, Twitter is not and has never been the most popular social network among Internet users. In fact, it has 353M active users, seven times fewer users than Facebook – the network with the highest participation.[13] However, if we look at its usage, Twitter, unlike other networks, is the microblogging platform par excellence in political, journalistic and/or activist fields. In fact, 64% of people use Twitter at least once a week to stay informed on political issues. Studies such as the one carried out by Pablo Barberá and Gonzalo Rivero (2012) show how political debate is strongly polarised on Twitter, as users with a greater political identification are those who participate most in these networks.[14] As a result, in network awareness surveys, Twitter ranks third behind Facebook and WhatsApp – out of the 16 shown on the graph. Furthermore, in January 2021, Twitter was the 11th most visited network worldwide and its mobile app the sixth most downloaded.[15] This means, despite having fewer users, it is a network that is well known by the general population due to its influence and relevance in the news and current affairs scene, which is why we could classify its consumption as social as well as individual. Hence the strategic importance we attach to it for the analysis of memory practices.

Twitter’s popularity must also be situated in geographical terms. The top 20 countries with the most users, in descending order, would be: USA, Japan, India, UK, Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, France, Philippines, Spain, Thailand, Canada, Germany, South Korea, Argentina, Egypt, the Netherlands and Colombia. However, the gap between numbers 1 and 20 is highly significant. The USA has over 70M users; Colombia has 3.8M.[16] In addition, five European countries can be found among the top 20 (25%). The Americas and Europe lead the territories with the highest number of users.[17] In contrast, developing countries suffer from a digital divide that hinders their access to networks, undoubtedly explaining in part their low presence on Twitter – regardless of the popularity of the social network in each region. Internet access remains undemocratic: 41.5% of the population does not have it, despite the fact that it is considered vital for accessing education, information and employment. In fact, the EU signed an agreement last year to reduce the digital divide that also exists within Western societies among the most vulnerable population strata.[18]

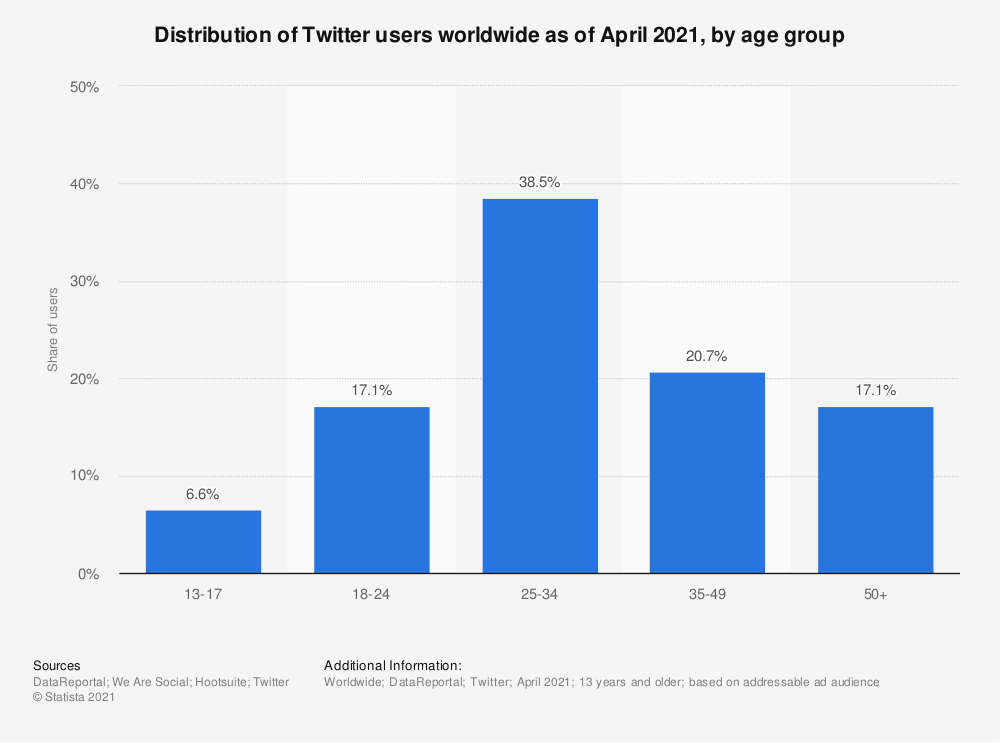

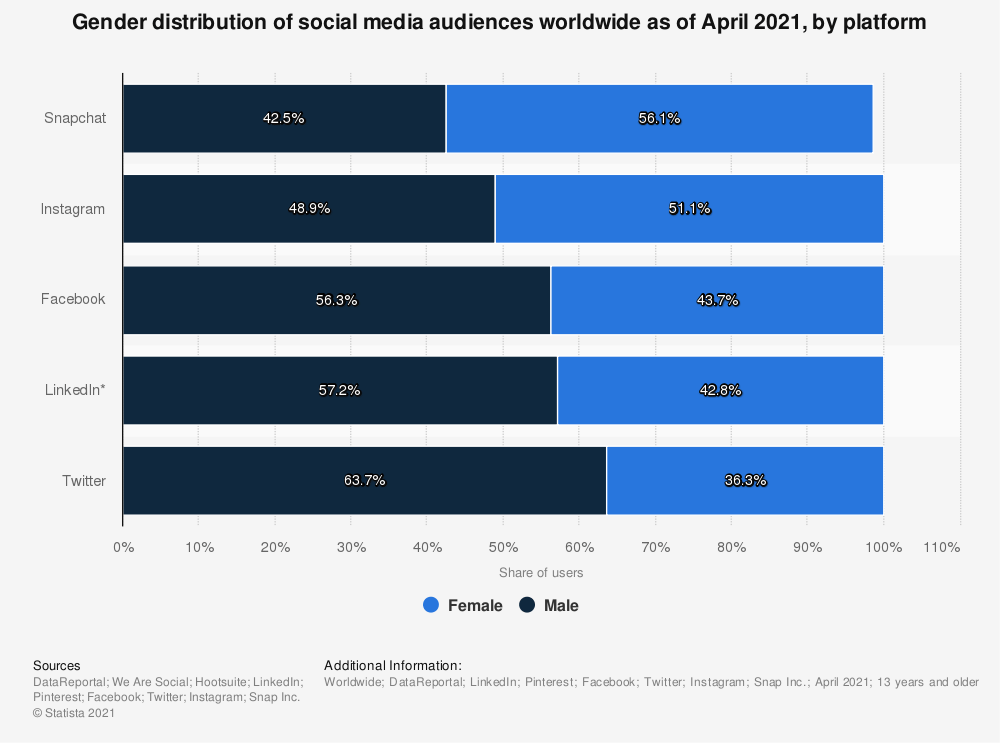

This quantitative, geographical reality should be complemented by more specific profile data. On one hand, age. Twitter is particularly popular in the 25–34 age group (38.5%), with a moderate presence among minors and also, especially, among adults over 50. The gender gap amongst Twitter users also deserves special attention, as it is the widest of all the social networks. In 2021, 63.7% of Twitter users were male and only 36.3% defined themselves as female. On other networks, the presence of both genders is somewhat more balanced, although in general terms it is also detailed (with the exception of Snapchat and Instagram). It should be noted that these gender and age figures translate almost in the same percentages to European Twitter use. The gender gap is undoubtedly an element of which we are acutely aware in presenting and analysing the data from the situated analyses, as it implies less female participation in the construction of these digital memory spaces. Moreover, the generational question may also provide added value, as it may allow comparison of memory practices and narratives of younger generations with those of their parents or grandparents. Internet and Twitter are not democratic in their access according to income, but elements such as socialisation with digitalisation are also a limit for people over 65. Likewise, elements such as the double working day and women’s reproductive work overload have historically also meant less time for political and digital participation.

Other important sociological data should be taken into account. For example, Twitter users have an above-average level of education, with a medium-high income. According to these data, the average Twitter user would be a young man of European or American nationality, with higher education and above-average income, who accesses Twitter via a smartphone. In this particular snapshot, which is neither generalised nor generalisable, there are structural conditioning factors (digital divide, double working day, etc.), but also a predilection of such profiles towards this space.

Twitter’s content policy considerations (fake news, hate speech and censorship)

A project on digital content analysis should include assessments of users’ online freedom and the potential that this space can have for the creation of hate speech. This reality is not alien to our project. As has been noted, digital memory spaces, like any other memory space, are a battleground for discourses where, not infrequently, the xenophobic extreme right participates with its own reinterpretation. We do not intend to initiate a debate or position on the limits of freedom of expression, nor do we intend to offer a code of good practice on content censorship. However, to procure some data on public and private policies against so-called fake news or hate speech is useful for understanding the functioning of social networks, especially Twitter. As we pointed out on prior occasions, the Internet allows the population to access a greater volume of information. However, it is not clear that this reality has improved critical analysis for the selection of rigorous accurate information – partially due to phenomena such as over-information. The Internet has two faces. On one hand, it allows us to diversify information, agents, agencies, interlocutors and messages; it also allows us to become content creators. It helps us gain quicker access to any reality in the world and even to escape the orthodoxy and direction of opinion exercised by the large media monopolies. We should not forget that the Internet and networks are particularly useful tools in contexts of dictatorships or journalistic hermeticism, where they have become a true countervailing power. Nevertheless, this dimension has its risks. In the same way as we see the informative capacity amplified, the misinformative or manipulative capacity increases proportionally. Fake news and hate speech discourses were not invented by the Internet, but in this medium they find a greater multiplicity of circuits through which to penetrate among users.[19]

We should also bear in mind that social networks are not in any case a regulated public service but private companies, which have their own privacy and content policies.[20] In this manner, these companies have become true arbiters of information, able to make independent decisions about what content to remove and what not to remove, what is dangerous and what is not, to identify what is false and what is real. We do not know the number of content pieces removed at Twitter’s decision, nor the number of accounts blocked. Neither do we have the reasons – but the debate on social networks’ power to decide what content is published is undoubtedly growing. The recent suspension of the account of the then US president Donald Trump drew widespread criticism in this regard, as a precedent and a demonstration of the power of these agencies in political intervention and control of speech.[21] Undoubtedly, this enormous power can serve both to censor legitimate criticism or opinions as well as hate speech against discriminated groups.

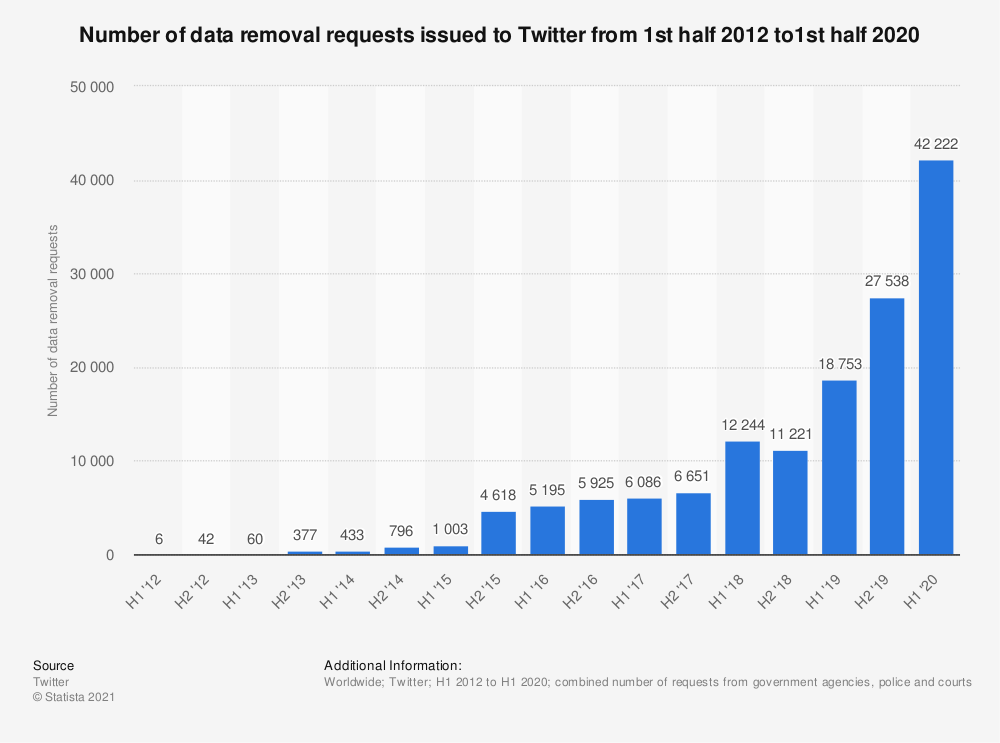

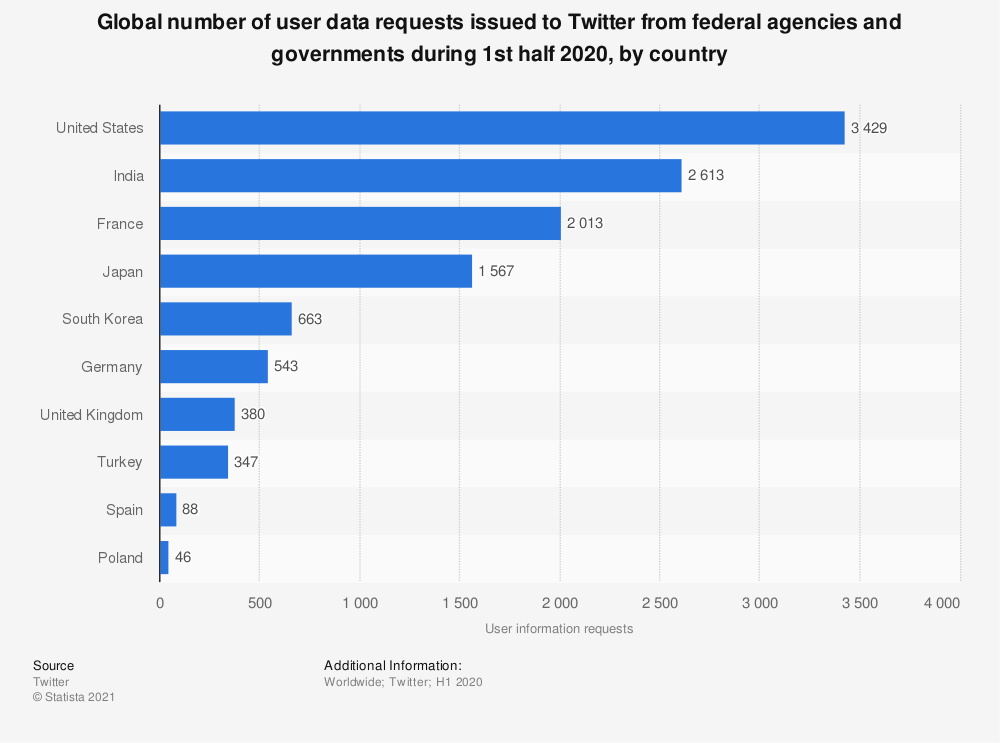

Another element to consider at this point is the actions of these networks in response to government requests or court orders. This is of particular concern in States with low levels of democracy or freedom of expression. For example, between January and June 2020, government agencies, police and courts in a multitude of countries submitted a total of 42,222 takedown requests to the microblogging platform Twitter. The latest Twitter Transparency Report shows that Twitter received approximately 53% more legal complaints globally compared to the previous reporting period. This was also the highest number of requests reported since the platform’s first Transparency Report was published in 2012. In other words, there is increasing state and legal control over the content of this platform – which may be seen in both positive and negative terms. The countries heading such requests were Japan, Russia, Turkey, South Korea and India, which accounted for more than 70 per cent of the total number of applications received per platform. Another important figure is the overall number of user data requests issued to Twitter by federal agencies and governments in the first half of 2020. This ranking, topped by the US, shows public-private collaboration in the field of cybersecurity, but has also ignited debates on user data protection.

The content of this report[22]

In this fifth report, corresponding to the first half of 2021, we have continued with the analysis of Twitter content that relates the past and the present in digital memory spaces through the study of various commemorations. Some of these events are sampled for the third consecutive year, enabling us to gain a good comparative basis on their evolution. We refer to Holocaust Remembrance Day (27 January), Europe Day (9 May) – within Europe – and the Day of Proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic (14 April) – within Spain. We have also decided to include a new event on this occasion, May Day (International Workers’ Day) – a global celebration that we wish to include on a continuous basis so as to have comparative elements of the phenomena that we normally detect in Europe (and to a lesser extent in the US) with more global narratives. This world celebration serves as the initial test of this pilot exercise.

Table I. Summary of sampling in this report

| Commemorations | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Date |

| International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Memory of the Holocaust Victims |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

27 January |

| Commemoration of the Second Spanish Republic

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

14 April |

| International Workers’ Day | ✔ | 1 May | ||

| Europe Day | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 9 May |

The COVID19 factor

These analyses’ context should be taken into account. Europe and the world have been plunged into a pandemic with serious health consequences for more than a year. The Covid19 crisis has submerged Europe and the world in a wave of lockdowns, breakdown in social relations and trauma. This event has profoundly affected our relationships with social networks, which have become much narrower, sometimes even the sole channel for socialising. An increase in users is noticeable on all networks, meaning that many more agents have become involved in creating content. COVID19 and the current situation arise repeatedly in content. According to the global report Digital 2021 by the advertising agency We are social,[23] social media grew by 13.2% in the previous year. 490 million new users joined social networks, reaching a total of 4.2 billion in the early months of 2021.[24] The time users spend on social networks also increased by 0.4% to an average of 2 hours and 25 minutes.

Case studies

International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Memory of the Holocaust Victims

The date 27 January commemorates the liberation in 1945 by Soviet troops of the Nazi concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau. The United Nations General Assembly officially proclaimed this date as International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust.[25] However, although it has a global dimension, this celebration has a particular impact in Europe, Israel and the US. The Shoah is undoubtedly one of the processes that has most marked contemporary collective memory, not only in Jewish society, but also in many European countries which were connected to this reality in one way or another during the Second World War. The horror of the camps, the mass deportation of Jews and the accounts of testimonies were a real trauma for post-war societies as they discovered the horror of the murder of 6M Jews, pondered the responsibilities and, above all, tried to explain – with more questions than answers – how this was possible. The memory of these events remains alive and in constant construction, reaching out forcefully to Twitter and networks as a whole. At least 267,836 tweets were created in 2021 (rising to 1,487,221 through RTs).

Data file

| Collection method | Streaming API |

| Collection period | 25/01/2021 to 30/01/2021 |

| Words searched | Holocaust

#holocaust, Holocausto #holocausto Holocauste #holocauste Holokaustoaren #holokaustoaren Shoah #Shoah Holokaust #holokaust Holocaust-Tag HolocaustTag יום השואה #holocaustday #WeRemember #memorialhistoricalday #HolocaustMemorialDay #holocaustremembrance #holocaustremembranceday #diaholocausto #díadelholocausto #Auschwitzherdenking #Auschwitz #Auschwitz75 Auschwitz #AuschwitzLiberation |

| Number of original tweets obtained | 267,836 |

| Number of tweets + RTs | 1,487,221 |

Evolution of participation

The evolution of activity on Twitter on Holocaust day peaked on the 75th anniversary celebration of the liberation of Auschwitz (2020). In 2019 it was significantly lower because the list of words searched was smaller: these parameters have been expanded each year by introducing more linguistic diversity. So comparison of 2020 with 2021 is more accurate. (The same words have been monitored on both dates, as can be seen in Table 2.) However, both in 2019 and 2021, we can say that there is less participation as there was no special anniversary celebration and no associated mass ceremonies.

The percentage of RTs compared to original tweets increased in 2000, falling slightly in 2021. The number of unique users participating also declined from 2020 to 2021.

Table 2: Evolution of participation

| Year | Original tweets | Tweets + RTs | % of RTs | Unique users |

| 2019 | 26,954 | 123,776 | 78.22% | 69,574 |

| 2020 | 453,154 | 2,615,474 | 82.67% | 1,111,775 |

| 2021 | 267,836 | 1,487,221 | 81.99% | 738,877 |

The following table shows the words selected for each of the years. In 2020 it was extended to other languages and included references to Auschwitz. In 2021 the same words have been kept, but 43% fewer tweets were collected.

Table 3: Words monitored

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Holocaust day

#holocaustday #WeRemember #memorialhistoricalday #holocaustremembrance #holocaustremembranceday Día del holocausto #diaholocausto #díadelholocausto Holocauste #Holocauste |

Holocaust

#holocaust, Holocausto #holocausto Holocauste #holocauste Holokaustoaren #holokaustoaren Shoah #Shoah Holokaust #holokaust Holocaust-Tag HolocaustTag יום השואה #holocaustday #WeRemember #memorialhistoricalday #HolocaustMemorialDay #holocaustremembrance #holocaustremembranceday #diaholocausto #díadelholocausto #Auschwitzherdenking #Auschwitz #Auschwitz75 Auschwitz #AuschwitzLiberation |

Holocaust

#holocaust, Holocausto #holocausto Holocauste #holocauste Holokaustoaren #holokaustoaren Shoah #Shoah Holokaust #holokaust Holocaust-Tag HolocaustTag יום השואה #holocaustday #WeRemember #memorialhistoricalday #HolocaustMemorialDay #holocaustremembrance #holocaustremembranceday #diaholocausto #díadelholocausto #Auschwitzherdenking #Auschwitz #Auschwitz75 Auschwitz #AuschwitzLiberation |

Analysis of the graphs[26]

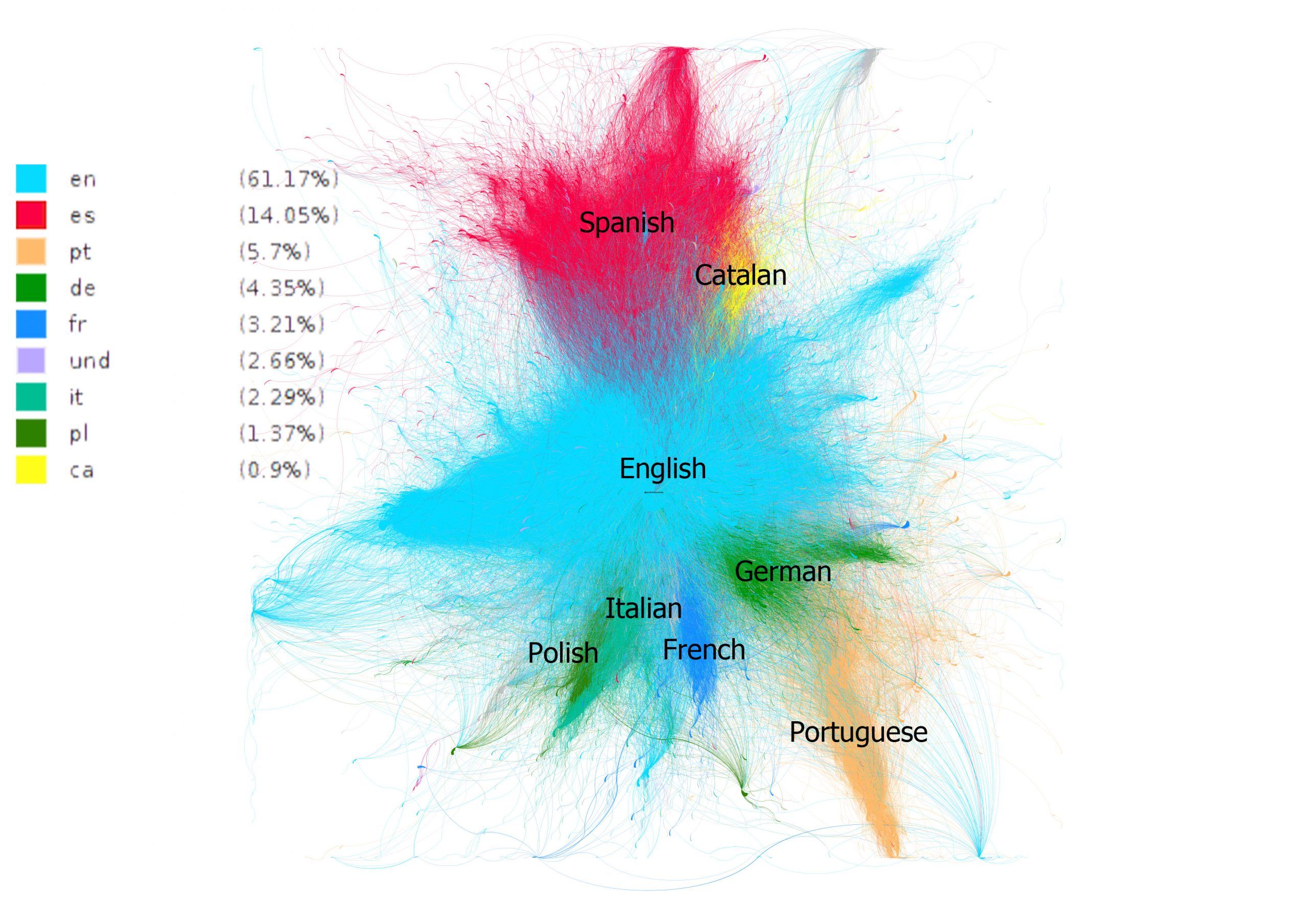

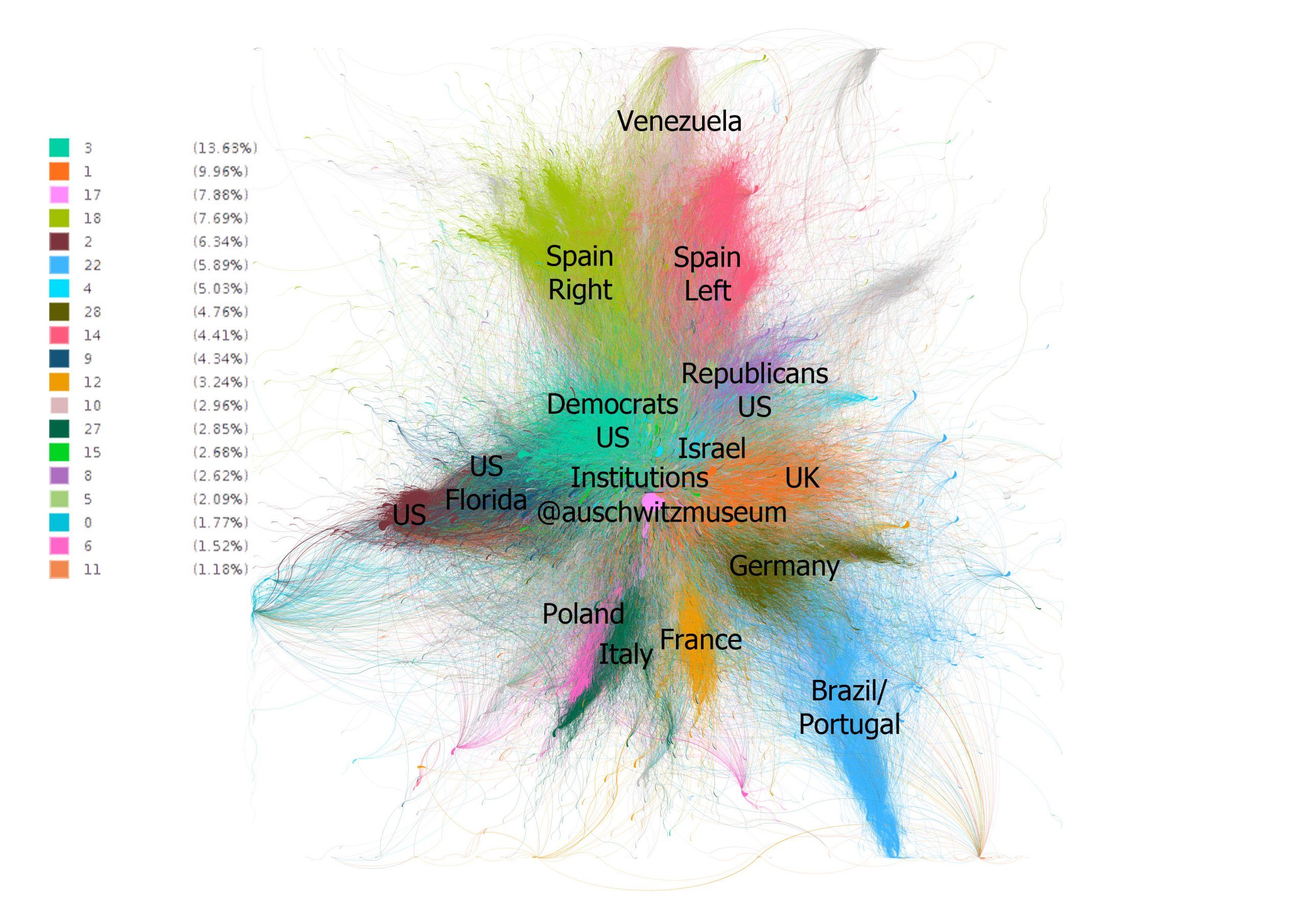

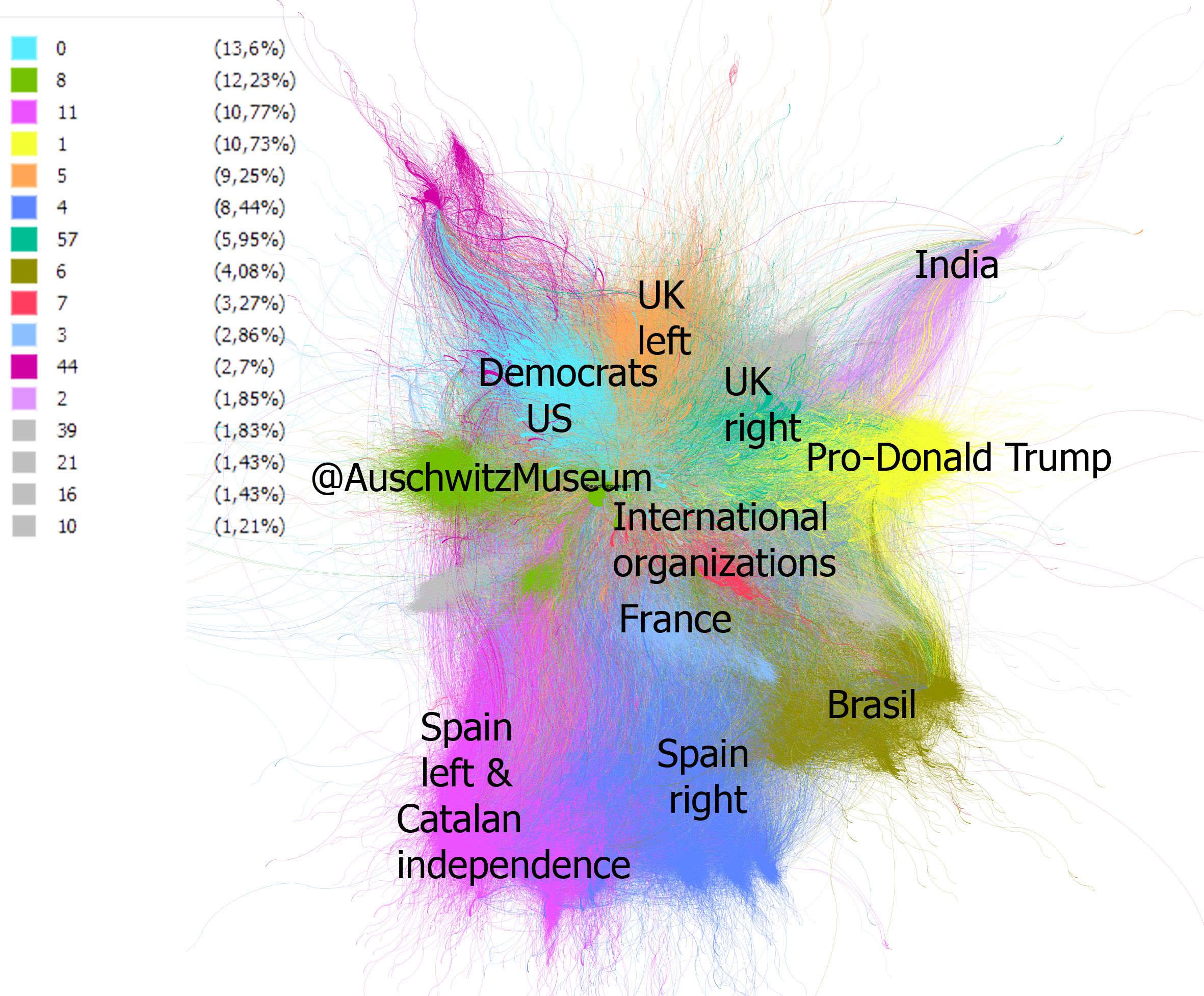

Normally, as we saw in previous reports, the criteria used to identify communities and define the graphs are linguistic, geographical (Graph 1)[27] and ideological. Although Twitter is a global tool, dissemination occurs locally and language is a barrier. These three factors are interrelated in the formation of communities in this case. For example, language generates communities that are meaningless without the ideological factor, since within the same linguistic interaction, discourses and messages may be diametrically opposed. Once these variables have been identified, the final structure of Graph 2 shows three blocks: at the top, tweets originating from Spain and Venezuela (a single linguistic community) are grouped together; in the centre are global institutions and NGOs, Israel, the US and the UK; At the bottom, tweets posted from Germany, France, Italy, Poland, Brazil and Portugal are grouped together. Ideological separation within linguistic and territorial communities is particularly evident in the US and Spain. In 2020, the UK was also divided along political lines, but in 2021 there is no such polarisation.

GRAPH 1. LINGUISTIC COMMUNITIES

GRAPH 2. FINAL COMMUNITIES.

In this second graph, five main communities stand out in particular according to the percentage of their members: the US Democrats (13.63%), the UK (9.96%), the @auschwitzmuseum (7.88%), the Spanish right-wing (7.69%), and a strange group in the United States (6.34%) where some accounts are now closed. These communities generated most of the content. With respect to 2020 (see Graph 3), following this structure, we observe less prominence of @auschwitzmuseum, less polarisation in the UK, more presence of the Spanish right than of the left, less activity of the US Republicans – probably due to the lack of momentum of Donald Trump’s followers. This shows the importance of the political context in the field of memory construction. The memory of the past is not alien to its present and presentism uses.

GRAPH 3. 2020 COMMUNITIES

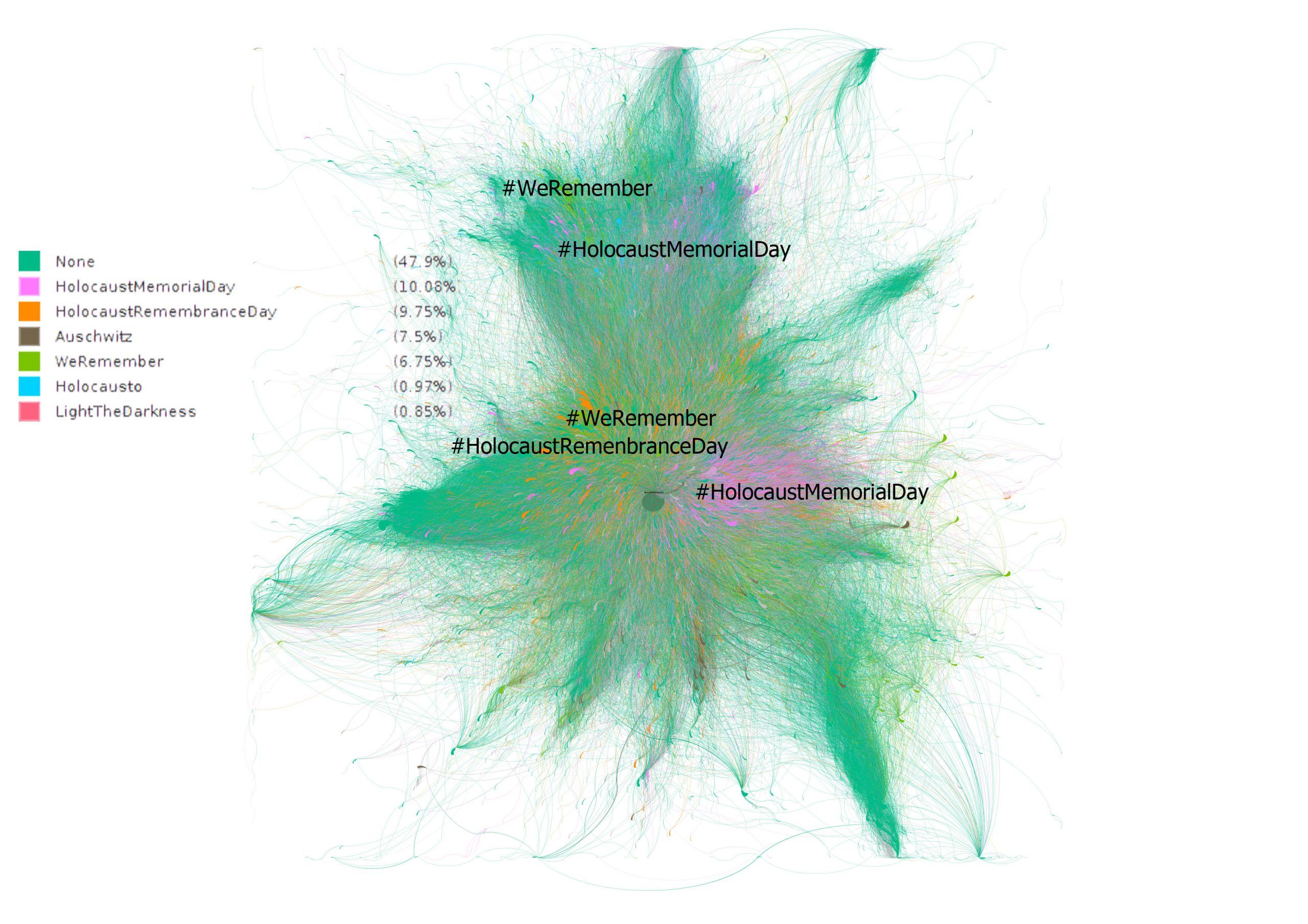

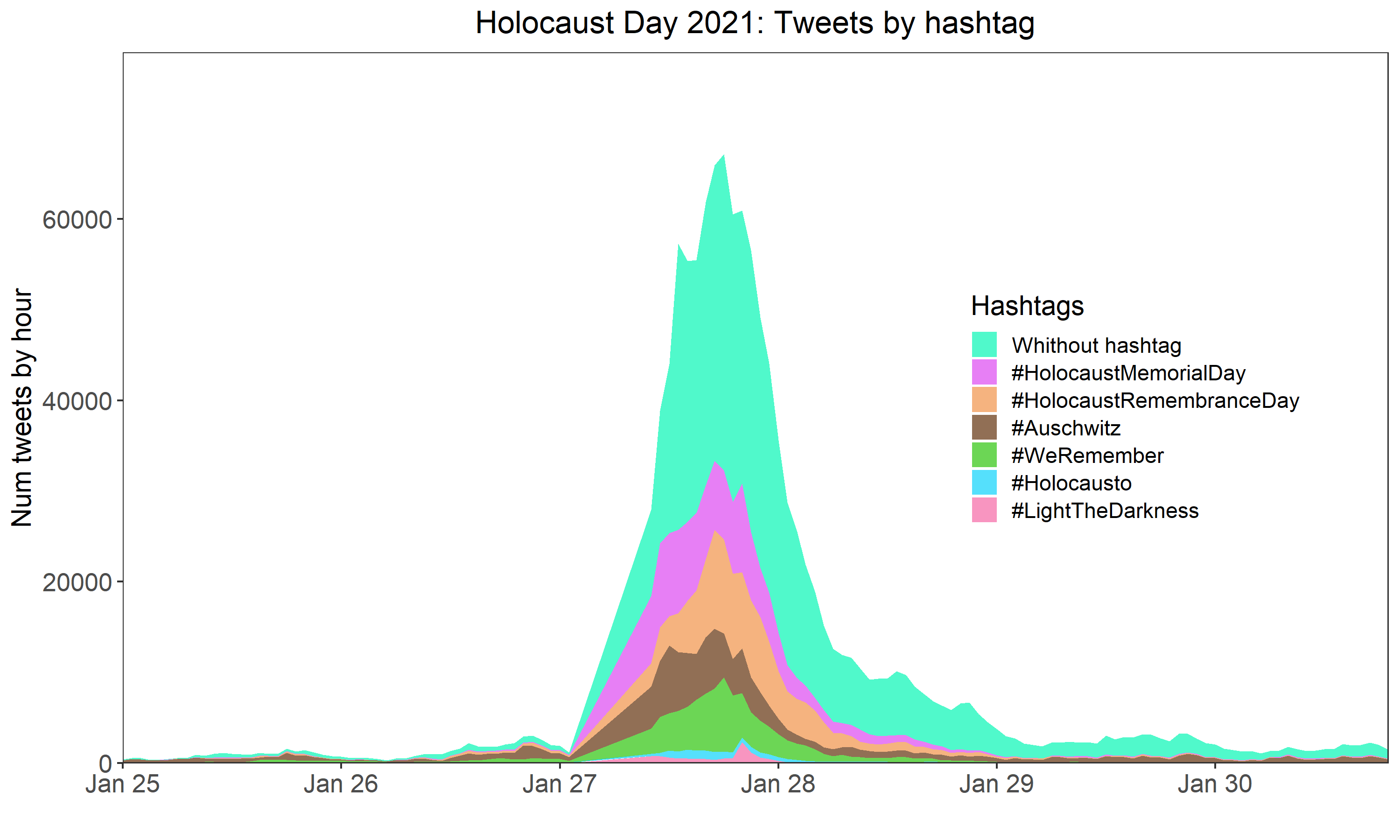

Generally tags are used in organised campaigns that seek to give visibility to a topic or to users who want their message to be read when it is searched for. In this case, only 52.1% of the messages disseminated included hashtags. This indicates that almost half of those who posted messages discussing the Holocaust did so without tagging it and that the search for this content was done more by keyword than by tag. In this way the messages were able to reach those who retweeted them via their timeline initially via both searches and trends. This reality is important for our theoretical positioning. The tag brings together discourses and memorial narratives in a more organised way, but the practice of digital memory is not restricted to it. However, we are particularly interested in this phenomenon, as we find two important elements in them: on the one hand, they are a more organised and traceable expression over time and, on the other hand, hashtags are also created/used by specific politicised communities. In the same way as collective memory, we could say that the hashtag, due to its collective use and limited to a group, can be better positioned as a catalyst and generator of memories. In this way, messages within hashtags tend to have a qualitative value in our analysis, without this signifying that we likewise fail to present and value the creation of more spontaneous, less organised content. In this regard, despite representing little more than half the content, it should be noted that compared to 2020, the number of messages with hashtags has increased by 13.27%. These tags were agreed upon in some areas, particularly in the Auschwitz Museum community and in the US Democratic and Republican groups. As can be seen in Graph 4, the most widespread were: #HolocaustMemorialDay(10.08%), #HolocaustRemembranceDay (9.75%), #Auschwitz (7.5%), #WeRemember (6.75%), #Holocausto (0.97%), #LightTheDarkness(0.85%).

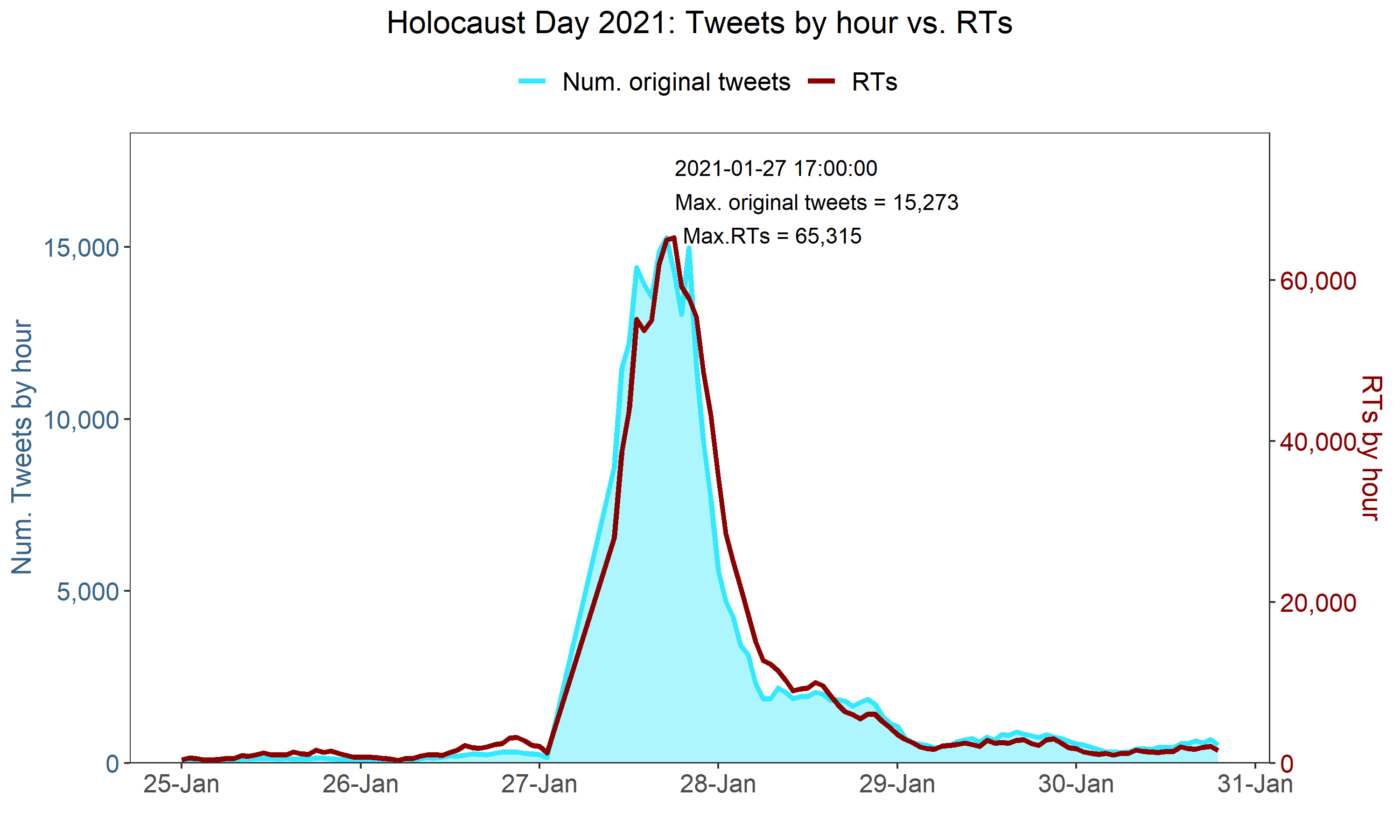

Temporal dissemination

An alternative view of the dissemination represented by graphs is the temporal evolution of the original tweets’ publication. This study considered original messages to be those that imply that the author has created his or her own message either by publishing a text, by replying to another user’s tweet or by quoting a tweet to which a comment is added. (This option is also called retweet with comment.) In all three cases it implies that the author has typed a text that involves more effort than pressing a key to disseminate it. On Twitter, there is a lot of amplification, with the percentage of retweeted messages being above 80% for most of the topics analysed. In this case, the percentage of original messages (tweets, quotes and replies) is 18.01%, so the percentage of amplification is 81.99%. Our position on this issue is that the agents generating memory are those who create the content; also that the social acceptance of this memory can be assessed through the level of amplification via RT – always taking into account the sociological profiles exposed, the Twitter bubble, gender factor and ascription to communities. The memories identified on the web, like all memories, must always be situated within their real context and reach.

The following graphs analyse the evolution over time of the publication of messages, both original and retweets. In previous reports the graphs were created only around original tweets due to limitations of the viewing tool. From this report onwards, in which the tool has been updated, the graphs will be based on the total number of tweets. Furthermore, a new graph on the reach and engagement of influential profiles has been added.

FIG. 1: ORIGINAL TWEETS VS RETWEETS

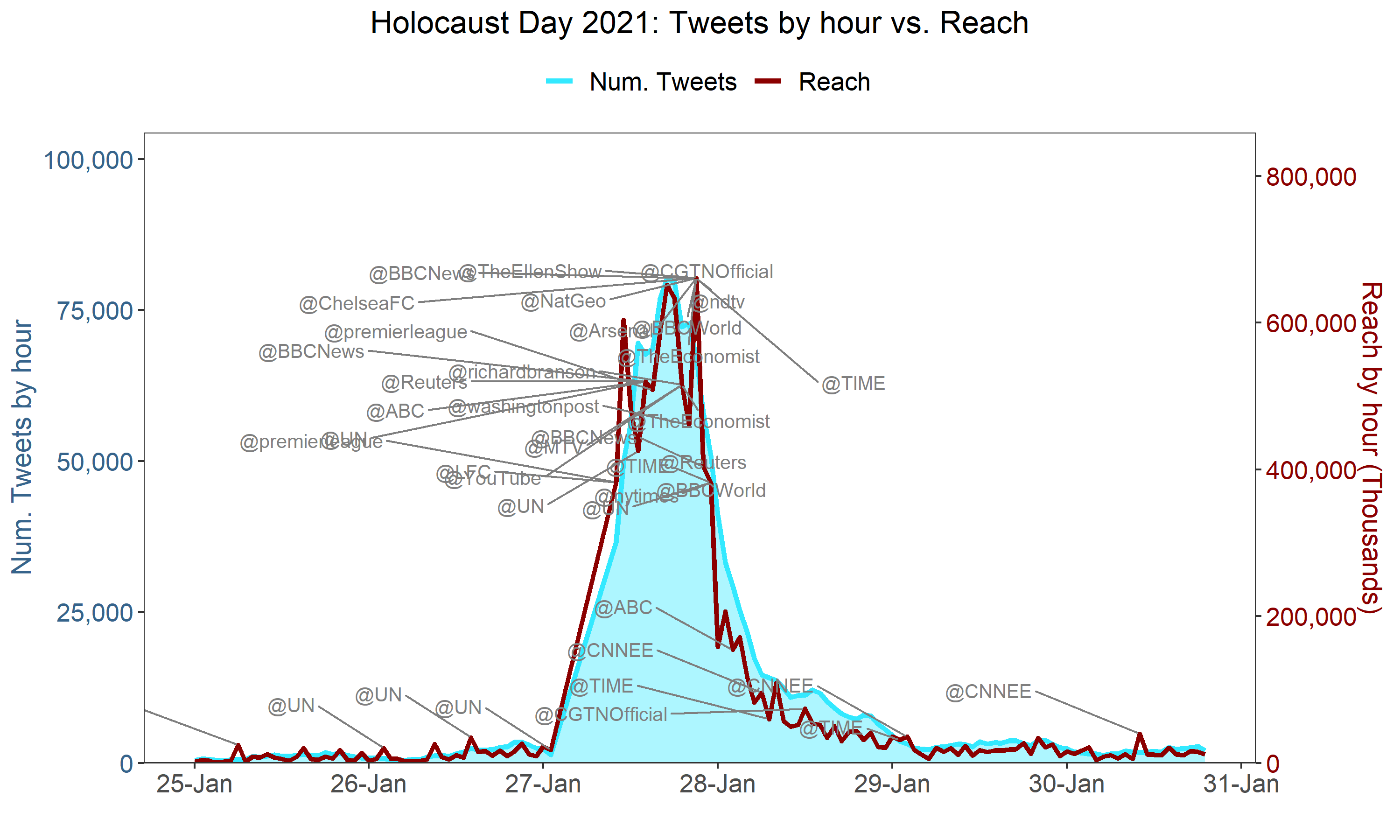

Activity was concentrated on 27 January, slowly declining over the following days. Figure 1 represents the temporal evolution of the original tweets posted and the RTs they received, both counted in one-hour intervals. The two variables represented have different scales, but are represented proportionally. The peak was at 17:00 (GMT), one hour later than in 2020. During that hour, 15,273 tweets were posted (16,439 in 2020) which received 65,315 retweets (113,832 in 2020). This time coincides with the working hours in Europe and America (the territories where this commemoration has the greatest impact).

The participation of relevant profiles is reflected in graph Fig. 2 which records profiles with more than ten million followers who participated. Most of them were Anglo-Saxon media and international organisations. The double-scale graph shows the relationship between the number of tweets posted in an hour, original tweets or RTs, and the possible reach.

Most of the original messages did not carry hashtags, as we have already noted. Their presence represented in Fig. 3 was concentrated on 27 January, with #HolocaustMemorialDay being the most frequent hashtag, followed by #HolocaustRemembranceDay, #Auschwitz, #WeRemember, #Holocausto and #LightTheDarkness.

The content

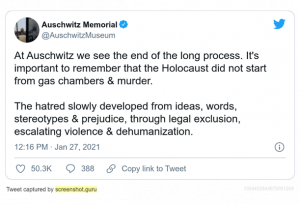

Having presented the general trends of this commemoration, it is necessary to situate the most relevant content. The top ten most popular messages are from politicians and institutions: Auschwitz memorial, Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, etc. With the exception of the second and third most circulated tweets, which were posted by profiles whose accounts are currently closed. They are not profiles related to politics, communication, NGOs or social activism. However, we are referring to ‘influencer’ profiles on the networks – with many followers and wide dissemination. They are a phenomenon that we should be aware of due to their enormous capacity for dissemination (second and third most disseminated messages, both without an associated hashtag).

Above: TWEETS 1 AND 6 OF THE TOP 10

Text of the tweet from the closed account: ‘i just logged off everything but i want to say please … please dont trend a # ~ im just a fan account and this could get me as well as other streamers in trouble. there are more important things to trend today such as holocaust memorial day. please be careful everyone’

Among the issues to be highlighted, the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict also formed part of the discourse on the commemoration of Holocaust Remembrance Day. In fact, at least 2,864 tweets made reference to this conflict, mostly taking sides and positioning themselves in favour of one of the parties. This is a trend that has already been noted and described in previous reports. It is clear that this date is also being used to construct the memory of the conflict in the region – through parallels between the Shoah and the situation of the Palestinians or by legitimising the state of Israel and its borders by highlighting anti-Semitic or terrorist practices on the part of the Palestinians. Regardless of the value judgement, it is inevitable that such a date will not be used in this presentist logic.

As a memorial phenomenon, we can especially highlight the #LightTheDarkness initiative, one of the most used hashtags on the day, helping to making a more or less unified memorial practice visible among the users who used it. The first tweet to use the hashtag was from actor David Schneider, who shared a tweet with a video telling the story of Holocaust survivor Nicholas Winton. This was the 23rd most circulated tweet of the day and through it the hashtag was popularised. It was subsequently used by numerous users to share photographs showing candles, menorahs or other types of light in memory of the victims. To follow the content trail, it seems we are dealing with a spontaneous, popularised expression that went viral for the first time in 2021. In 2022, we will be monitoring to see if it displays continuity, possibly becoming a more or less fixed memorial formula on the network, as we consider that these phenomena may be of particular interest in the establishment of new practices.

Lastly, we did not detect Holocaust denialist discourses using the commemoration to be significant on the network. In fact, most of the content that used this word in the various languages criticised such positions or mentioned COVID19 pandemic denialism.

Commemoration of the Second Spanish Republic

The 14 April is a very important date in Spain’s commemorative calendar. On 14 April 1931, the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed, inaugurating a brief democratic period between two dictatorships – Primo de Rivera’s (1923–1930) and General Francisco Franco’s (1939–1975), following the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). The Republic barely lasted six years, but it is remembered by a segment of the population as a time of great democratic advances, including recognition of women’s suffrage, as well as educational and agrarian reforms. This progress was abruptly and traumatically halted. In July 1936, part of the Spanish army, together with conservative and fascist sectors of society, took up arms in an unsuccessful coup d’état that triggered the Civil War. After the defeat of the Republic, the enduring Franco regime erased and censored the public memory of that brief democratic period, persecuting and repressing its defenders. For its part, the Republican government in exile maintained a certain memorial practice, which did not return to Spain with significant weight until the arrival of democracy. However, after the transition to democracy, there was no public or official recognition by the Spanish state either – with certain municipal and regional exceptions. For this reason, 14 April has never been an officially recognised commemoration, although it is de facto celebrated by a part of society who feel a strong link to this past. Another sector of society, however, continues to reject it, making 14 April a date on which certain tensions from the past still overflow. Herein lies our interest in smapling this commemoration: its consolidated practice has taken place on a less institutional, more informal level, led mainly by associations and entities working for the Republican memory of the Civil War and anti-Francoism. This has facilitated the proliferation of popular, activist discourses and practices, which in turn clash with discourses nostalgic for the dictatorship, especially with the rise of the new Spanish extreme right.

Data file

| Collection method | Streaming API |

| Collection period | 12–18 April 2021 |

| Words searched | #14abril

#14deabril #14AbrilRepublicaYa 14 abril república 14 abril republica subcampeones 1939 |

| Number of tweets obtained | 30,728 |

| Number of tweets + RTs | 197,442 |

Evolution of participation

The evolution of Twitter activity on 14 April reached its highest point in 2020. In 2021 there was less participation than in 2020, despite the fact that it was the Second Republic’s 90th anniversary. In 2021 the percentage of RTs to original tweets increased by just over one point compared to 2020. However, the number of unique users who participated decreased by 23.31%. One reason for this decline may have been the lower turnout of the radical right, which was considerably more significant the previous year. Another explanation is that 14 April 2020 coincided with the total confinement of the Spanish population, a fact that explains a higher participation of users in the network.

Table 1: Evolution of participation

| Year | Original tweets | Tweets + RTs | % of RTs | Unique users |

| 2019 | 11,180 | 86,714 | 87.10% | 36,705 |

| 2020 | 36,296 | 216,404 | 83.22% | 104,932 |

| 2021 | 30,728 | 197,442 | 84.43% | 80,471 |

The following table shows the words selected for each of the years. In 2020 it was expanded to variations of the #14April hashtag and direct references to the republic were removed to avoid false positives. In 2021, the same search has been maintained as in 2020 but 8.76% fewer tweets have been collected.

Table 2: Words monitored

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| #14deAbril

#VivaLaRepública #IIRrepública Segunda república |

#14abril

#14deabril #14AbrilRepublicaYa 14 abril república 14 abril republica subcampeones 1939 |

#14abril

#14deabril #14AbrilRepublicaYa 14 abril república 14 abril republica subcampeones 1939 |

Analysis of the graphs

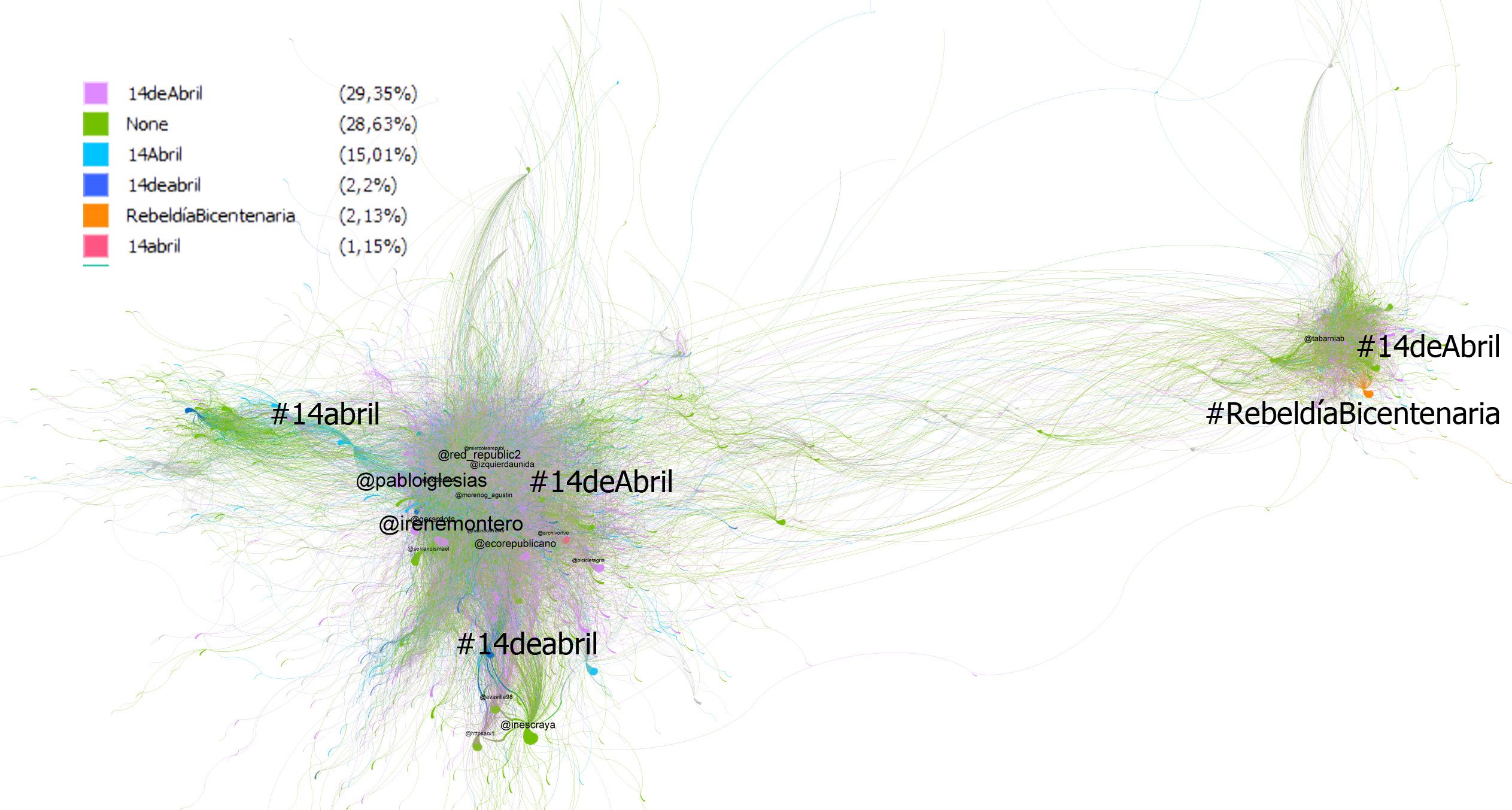

At the technical level, the profiles belonging to the giant component (largest subgraph whose nodes are all connected) were analysed. A second filter was applied to remove very small clusters, whose size is less than 2% of the profiles. These groups are often very disconnected, appearing distanced from each other in the graph display, causing it to be less than optimal. With this criterion, the percentage of profiles included is 80.53%. On the other hand, linguistic or territoriality criteria, intersecting with the ideological profile, generally serve – as we mentioned above – to identify communities. However, in this commemoration, the linguistic or territorial axis loses weight due to its specific circumscription to the Spanish context. Thus, the ideological criterion gains weight in the graph’s configuration. However, the linguistic reality is by no means homogenised, as in Spain the weight of Catalan on Twitter is particularly relevant and makes up a community of its own.[28]

Graph 1 shows four areas associated with ideology and geography. The date 14 April is also the Day of the Americas, which is why two Venezuelan groups, separated by ideology, use the HT #14April. The other two groups correspond to profiles that posted messages related to commemorating the Second Spanish Republic. Since the Venezuelan groups have a size greater than 2% of the profiles and are connected to the Second Republic groups, they appear in the graph. As can be seen in the graph, these groups are distantly connected to each other and to their ideological affinities, but there is hardly any connection between opposing ideologies and different countries (Spanish left versus Venezuelan right and Spanish right versus Venezuelan left). These connections between like-minded country/ideology signify that a small group may be talking about both celebrations. The structure is similar to that of 2020, forming a square in which each of the blocks is placed at a vertex.

In order to limit the context to the dissemination of tweets related to the Second Republic, the Venezuela groups have been eliminated (Graph 2). The final structure is separated into two blocks: for and against the commemoration. We therefore perceive that the commemoration is particularly polarised. On the one hand, in a single group, there is the radical right (in green), which accounts for 15.59% of participants. Its participation is down almost four points from the previous year (19.25%). The opposing block is a mix of republican groups, closely related to political groups such as Podemos, PSOE, Catalan users and user profiles that support the commemoration. Within this block, the largest group is of Podemos sympathisers, representing 23.77% of profiles. The previous year it was 7.27%, so the 2021 increase of 16.5 percent is significant. PSOE supporters also increased their participation (6.59% in 2021 compared to 2.35% in 2020), as did the Catalan community (7.97% in 2021 versus 3.52% in 2020). The structure of connections is similar to that of 2020 except for the Catalan group which seems less connected and more peripheral.

Through this final graph we can see that in the 14 April 2021 celebration we observe a stronger presence of left-wing parties facing the radical right, which is decreasing in participation (see Graph 3). Catalan accounted for 5.9%, almost two points higher than in 2020. Portuguese outperformed English, which is barely present. However, as mentioned, we are missing Galician and Basque.

Most tweets had an associated hashtag (Graph 4). Only 28.63% contained no tags, with the majority corresponding to an independent search for ‘14 de abril’. The most popular hashtags were #14deAbril (29.35%), used by both the pro- and anti-Republic blocs, and #14Abril (15.01%). In this sense, the hashtag itself was both a multiple memorial space and a space of conflict, as communities were not significantly segregated around different expressions. However, the radical right-wing group does include the hashtag #RebeldíaBicentenaria which corresponds to a tweet with more than 1000 RTs from the currently suspended @edelyisa profile. The tweet read:

‘Feeding the Soul “Do not let your heart be filled with anguish. Trust in God” – John, 14:11 Happy and Blessed Monday @edelyisa #RebeldíaBicentenaria.’

Although @edelyisa is a profile in a Venezuelan group, profiles from the radical right-wing bloc retweeted it in the context of the Spanish commemoration. For this reason the hashtag appears in that group.

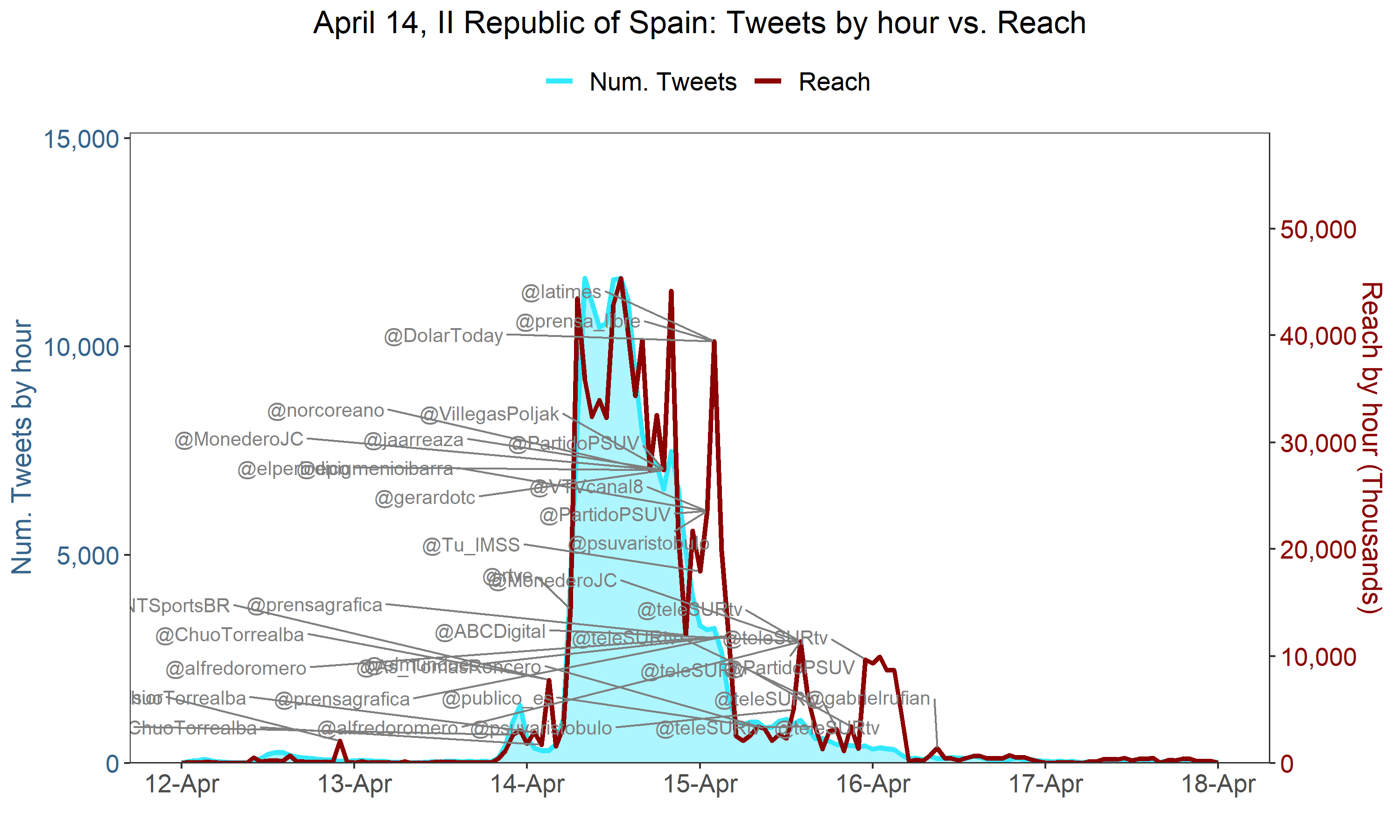

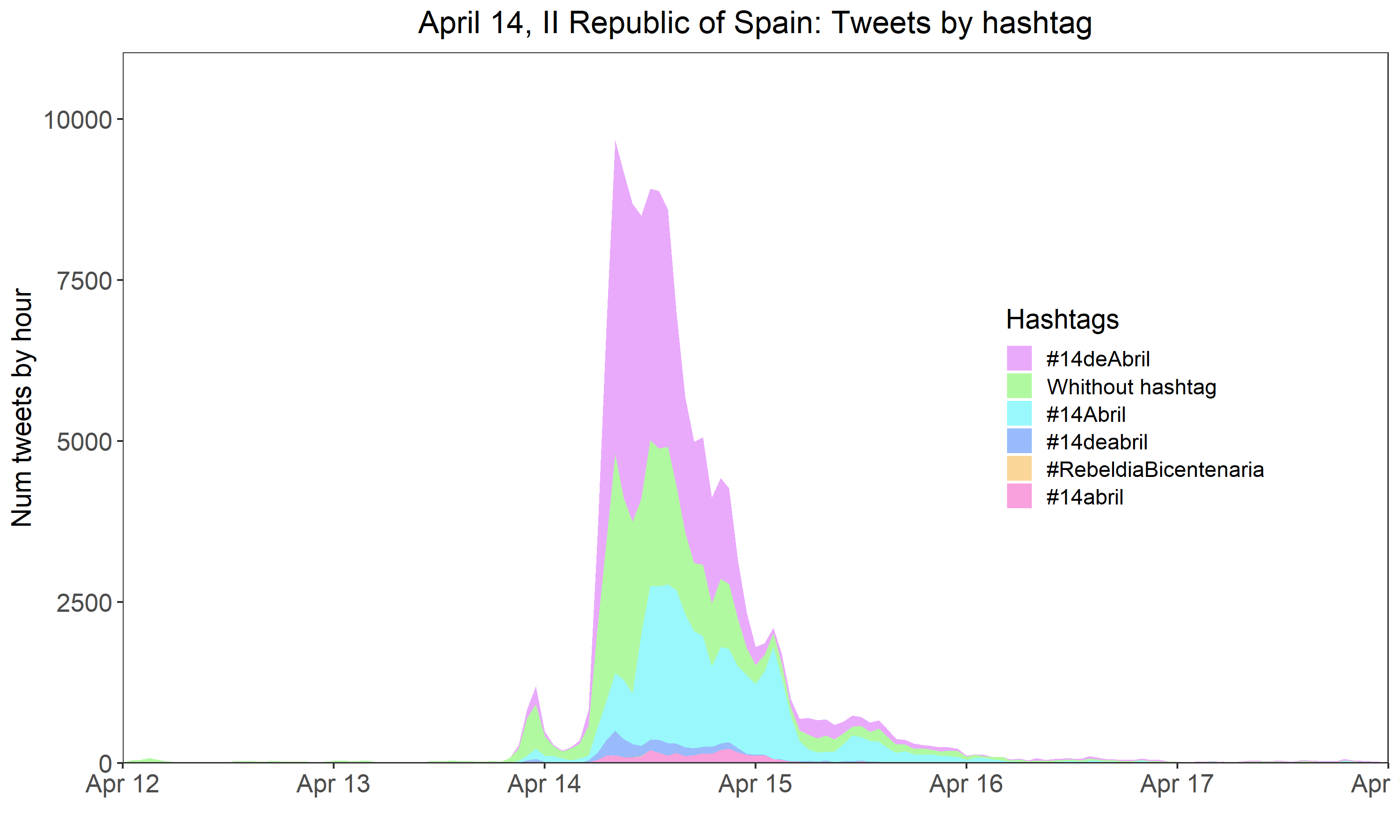

Temporal dissemination[29]

As is usual, intensity on the days before and after the celebration day was lower. The bulk of the tweets were concentrated on 14 April. The participation of relevant profiles – an innovation in 2021 – is reflected in Fig. 1, which records profiles with more than 500,000 followers who participated each hour. Most of them were media, leaders, political parties and activists. The double-scale graph shows the relationship between the number of tweets posted in an hour, original tweets or RTs, and the possible reach.

Likewise, the presence of hashtags in the tweets (Fig. 2) was also concentrated on 14 April, with the most frequent hashtag #14DeAbril, followed by #14Abril. On this point, we consider it very relevant that the 14 April celebration has a predominance of hashtags over ‘free’ content, especially compared to the other commemorations in this report. This makes it easier to situate the hashtag itself as the space of memory, showing a certain cohesion of the phenomenon. In this way, memory is generated in a specific space rather than in scattered locations, and can be more easily sampled over time.

Analysis of the content

It is worth mentioning that, among the ten most disseminated messages during the day, nine belong to the left-wing ‘Podemos’ community. This means that, on the one hand, during the day there was a predominance in the dissemination of the left-wing message, favourable to the commemoration, over that of the right-wing and opposing agents. As we mentioned above, on Twitter there is a greater number of users who identify with the ideological left, a fact that may explain this phenomenon – which should not be considered representative of the social reality outside the networks. On the other hand, within the digital left, there is a certain hegemony of sectors related to Podemos over other parties such as the PSOE – the winner of the latest elections and with a larger social base. In this regard, we should remember that Podemos is a young party, created in the aftermath of the 15M movement. It arose partially on the networks. It is therefore normal for its followers to be over-dimensioned in these spaces: a clear example of what we previously dubbed ‘Twitter bubbles’. Most of the Podemos network’s messages served to augur a third Republic, at a time when the Spanish monarchy is in more doubt than ever.

Above: TWEETs #1 and #2. Bellow, TWEET#6

In this top ten we found only one message against the commemoration, belonging to the account @Tabarnia_BNC (tweet#7, below). It intended to disqualify the Second Spanish Republic, detailing its repressive history. This tweet had quite an impact among the right-wing sectors that participated in the hashtags on 14 April.

Other striking messages were from VOX supporters, using the hashtag to offer the far-right leader Santiago Abascal congratulations on his birthday, 14 April. This coincidence was used by both communities (for and against).

Lastly, as an element of rupture with the previous commemoration, we note that this year we did not detect as many parodies or irony, as occurred in 2020. No doubt a climate of greater confrontation favoured this satirical phenomenon in the last edition.

International Workers’ Day

May Day, International Workers’ Day or Labour Day has been included in this report for the first time. Undoubtedly, this is a key celebration in the labour movement’s memory, evoking the history of the Chicago martyrs and past and present trade union struggles – especially within the socialist, communist and anarchist movements. In fact, it was first established as a commemoration of the Second International in 1889, although today it is a bank holiday in many parts of the world. However, there are significant exceptions. For example, in the USA, Canada and the UK – and by extension in many of their former colonies – Labour Day is celebrated on the first Monday in September. Therefore, the May Day date has less impact.

The decision to include this date in the report is based on the idea of expanding the samples with commemorations of a different nature, but also with the aim to go beyond a European framework and include global commemorations so as to situate these narratives’ reach in other geographical contexts.

Data file

| Collection method | Search API |

| Collection period | 30 April – 3 May 2021 |

| Words searched | #1deMayo

#DiaDelTrabajador #fetedutravail #1erMai #1Mai #TagderArbeit #MayDay #LaborDay #InternationalWorkersDay #1stofMay #1maggio #1deMaio |

| Number of tweets obtained | 94,146 |

| Number of tweets + RTs | 616,667 |

Evolution of participation

As this is the first time that Labour Day has been analysed, we cannot compare it with previous dates. The collection was undertaken using Twitter’s SEARCH API by looking at terms related to the celebration of Labour Day that were trending on 1 May in Spain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, UK and EU. In this regard, this year we have not yet been able to include trends in parts of the world where Twitter has considerable impact, such as China, India, Russia or Turkey – but which we intend to include in the future report so as to compare Twitter’s reach and ability to generate memorial narratives in these contexts.

The first data collection furthermore included tags such as ‘1st of May’ or ‘1 de maio’ in addition to the tags given in the file. More than one million tweets were obtained, but the network analysis found many false positives; i.e. tweets that included these expressions but did not correspond to the Labour Day celebration. These out-of-context tweets were grouped into communities separate from the core groups, but not entirely isolated. Most of the tweets from these outlying groups did not contain hashtags related to the celebration, so the selection criterion was to choose tweets containing hashtags that had been trending on 1 May.

After the selection process, 616,667 tweets remained, 94,146 of which were original, meaning 84.73% were RTs. Most of the discarded tweets were from profiles tweeting in English with the phrase ‘1st of May’ for various reasons (commercial, entertainment and greetings). A large number of profiles from Brazil also used the expression ‘1 de maio’ for topics such as sports or protests against President Jair Bolsonaro.

Analysis of the graphs

To generate the graphs, the profiles belonging to the giant component (largest subgraph whose nodes are all connected) were analysed. With this criterion, the percentage of profiles included is 91.67%. However, it should be noted that the groups detected were highly dispersed – none of them exceeded 10% of users. This is because the commemoration of Labour Day is celebrated differently in each country and there are no global slogans – each trade union or party creates its own tag. This makes it difficult to sample, with the most impactful tags containing institutional messages.

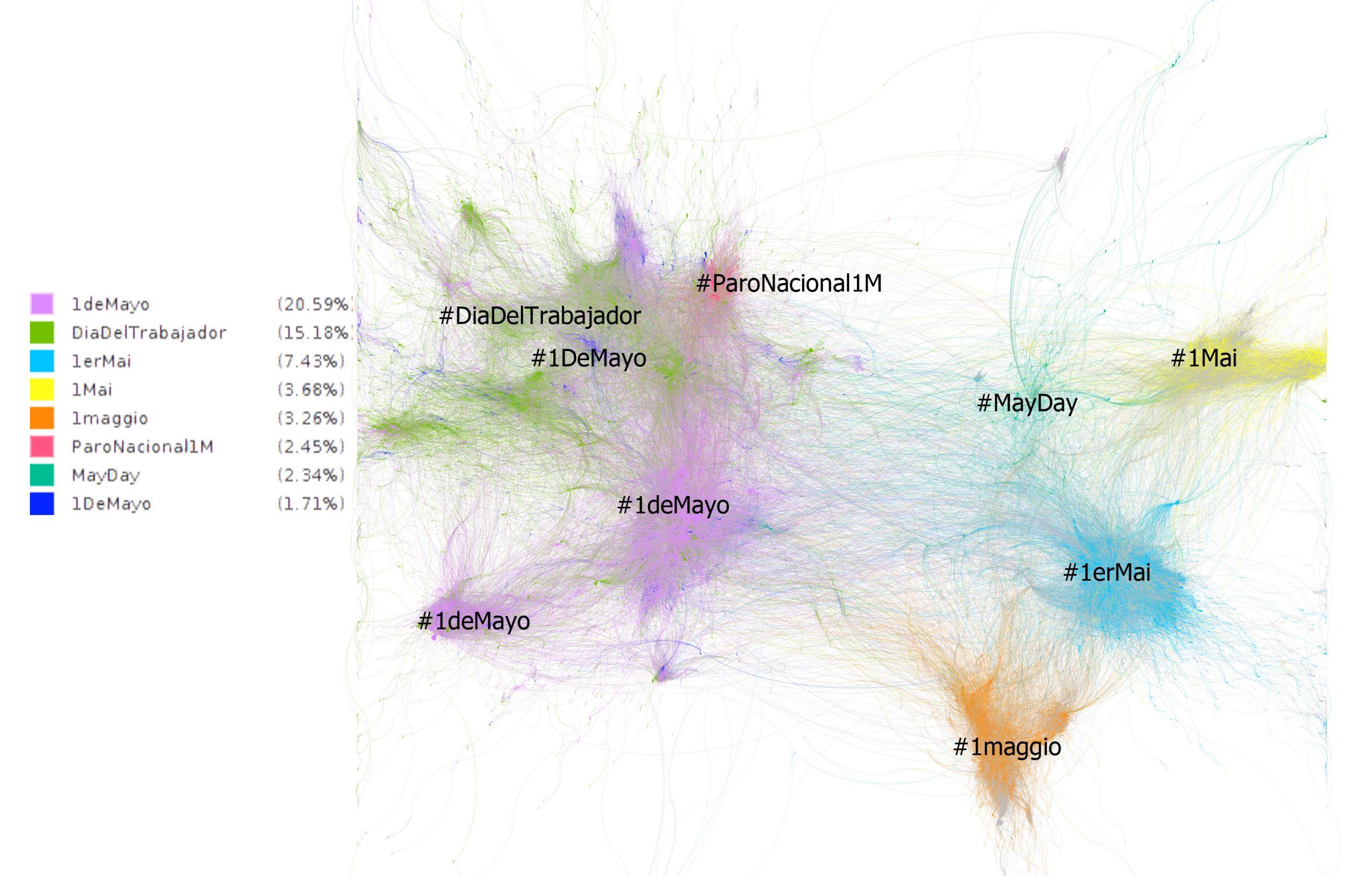

Graph 1 shows a structure based on geography, language and ideology, in that order – again linking the three elements that shape communities. On the left is a block of communities from different countries that are closer to each other because they are all Spanish-speaking. On the right are Italy, France, Germany and, weakly connected, English-speaking profiles – probably because in these territories, as mentioned above, Labour Day is celebrated in September.

GRAPH. 1 TWEET DISSEMINATION BY COMMUNITY

Some countries are further divided along ideological lines: Spain, Argentina, Venezuela, Germany and France. Spanish-speaking countries show a more marked polarisation as the ideological poles are further apart, with Spain being the most polarised country. There are also connections via ideological currents between countries and through different language groups. However, we know these data should be analysed with caution as they represent a European–Latin American snapshot, without its global magnitude. Neither can it detect each trade union’s or political party’s tags or slogans. It moreover ignores European linguistic plurality, limiting the search to hegemonic languages. We should furthermore recall that May Day is a hugely significant holiday for the left and the workers’ movement, but that it is not united into a single ideological, geographical or linguistic structure. For next year, therefore, we will need to improve our search criteria earlier.

Language distribution (Graph 2) highlights the language blocks more clearly. Spanish was the predominant language with 57.42%. It was followed by French with 15.06%, German with 8% and Italian with 7.19%. The percentage of tweets in English was a testimonial 5.57%, being as it is the predominant language in international events. Whether this was due to a lack of interest in the 1 May celebration – as it was not the date for Workers’ Day – or because the right words were not picked up, could not be determined. It should also be noted that the hashtag #LaborDay in American English was sampled, but not #LabourDay, in British English, used in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. This could have produced a bias in the results.

GRAPH 2. BY LANGUAGE

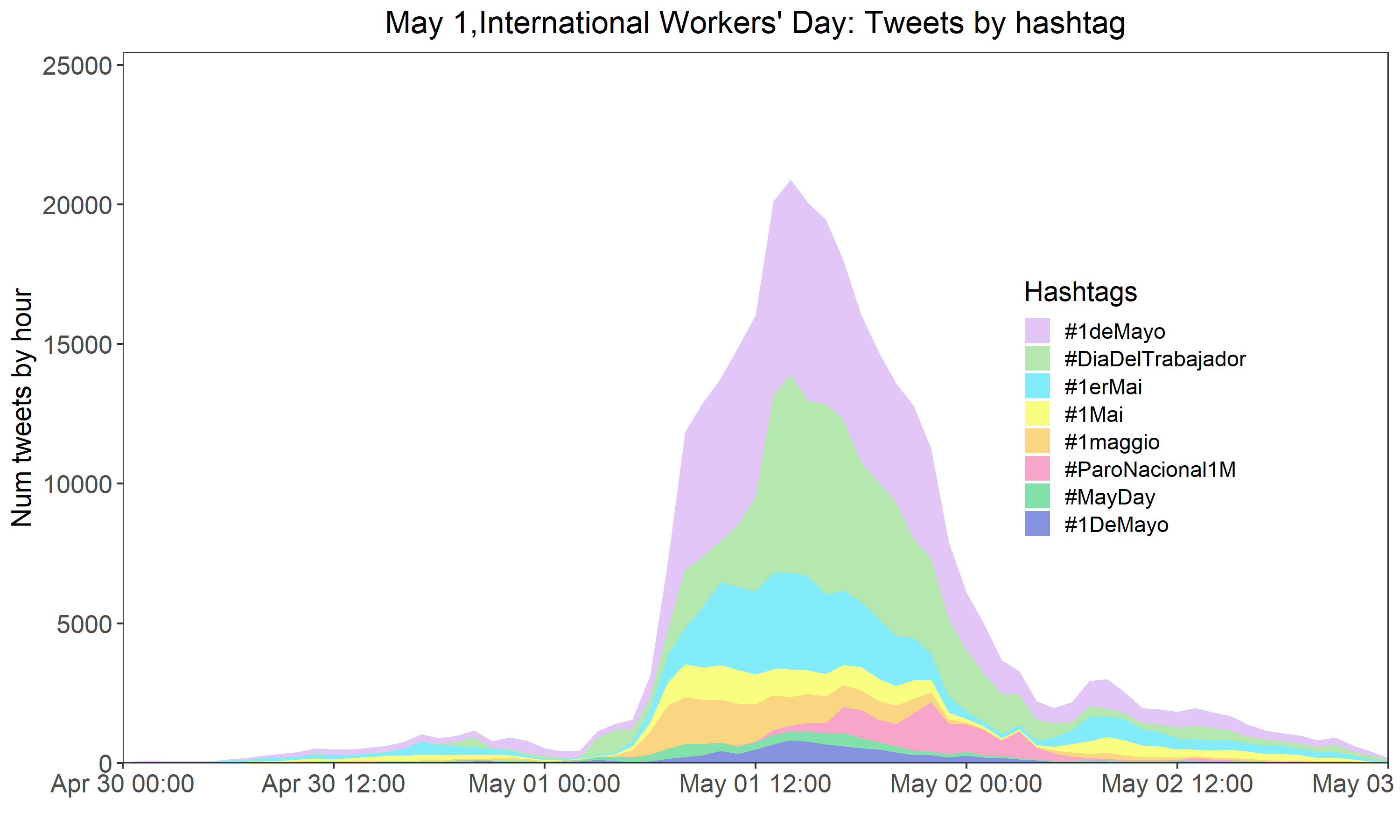

In this case, all tweets were tagged to ensure that they belonged in the context of the 1 May celebration. The tags were used differently in diverse countries. In Spain, #1deMayo was used, while in Latin America #DiaDelTrabajador was predominant. In Colombia, as well as #1deMayo, the hashtag #ParoNacional1M, related to the events they are experiencing, was very frequent. In Italy #1maggio prevailed, in France #1erMai, in Germany #1Mai and in the English-speaking zone #MayDay. It should be noted that in this celebration we do not have an amount of content generated without tags. Including keywords such as worker or work would have meant collecting millions of tweets that, for the most part, probably did not refer to the celebration. But it also means not being able to show the true reach, as it is likely that there was more content without tags than with tags.

GRAPH 3. ON RTS BY HASHTAGS

Temporal dissemination

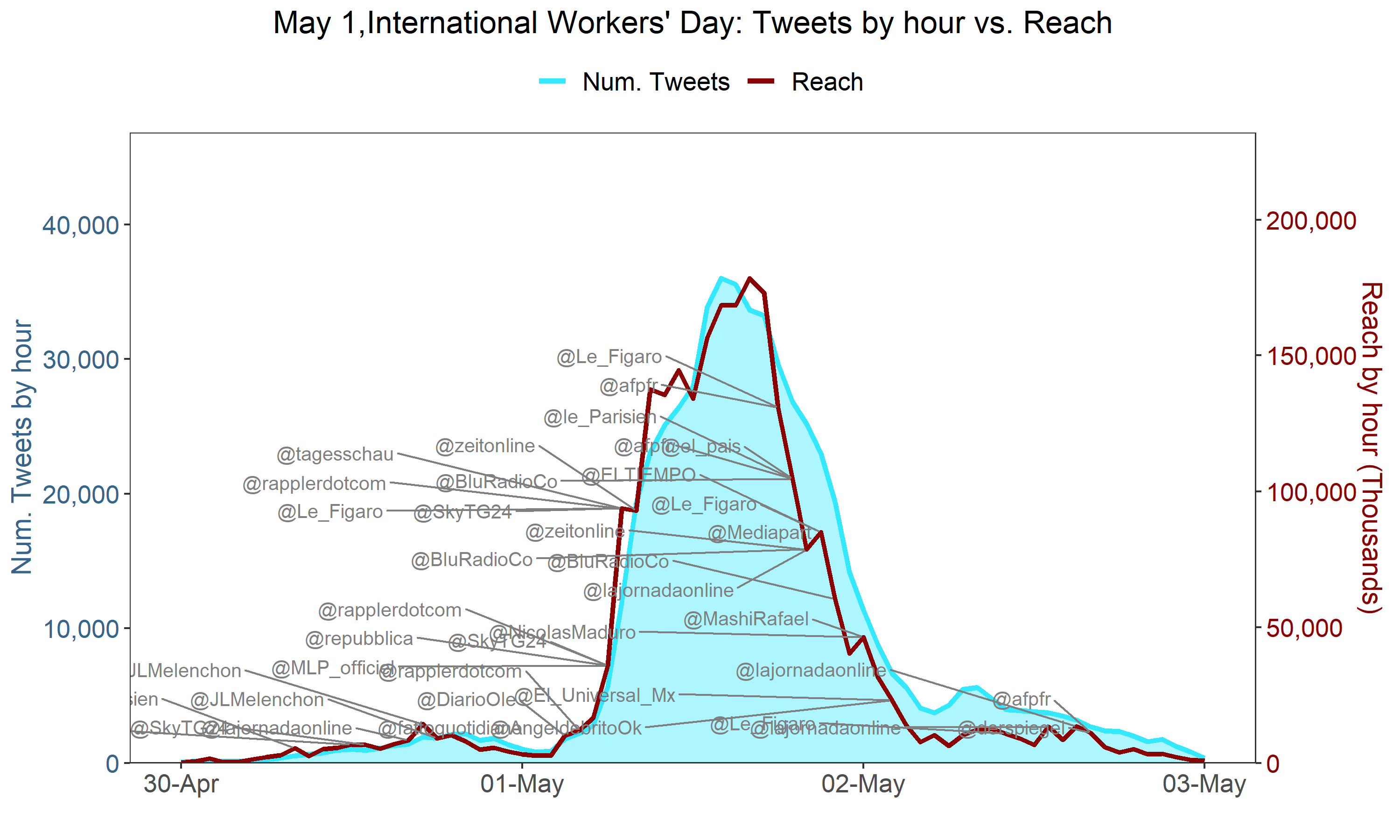

As is usual, intensity on the days before and after the celebration day was lower. The bulk of the tweets were concentrated on 1 May. The peak was at 15:00 (GMT) when the American and European working day converged. Furthermore, the participation of relevant profiles is reflected in Figure 1, which records profiles with more than two million followers who participated each hour. Most of them were media or political party leaders.

FIGURE 1. TWEETS VS REACH

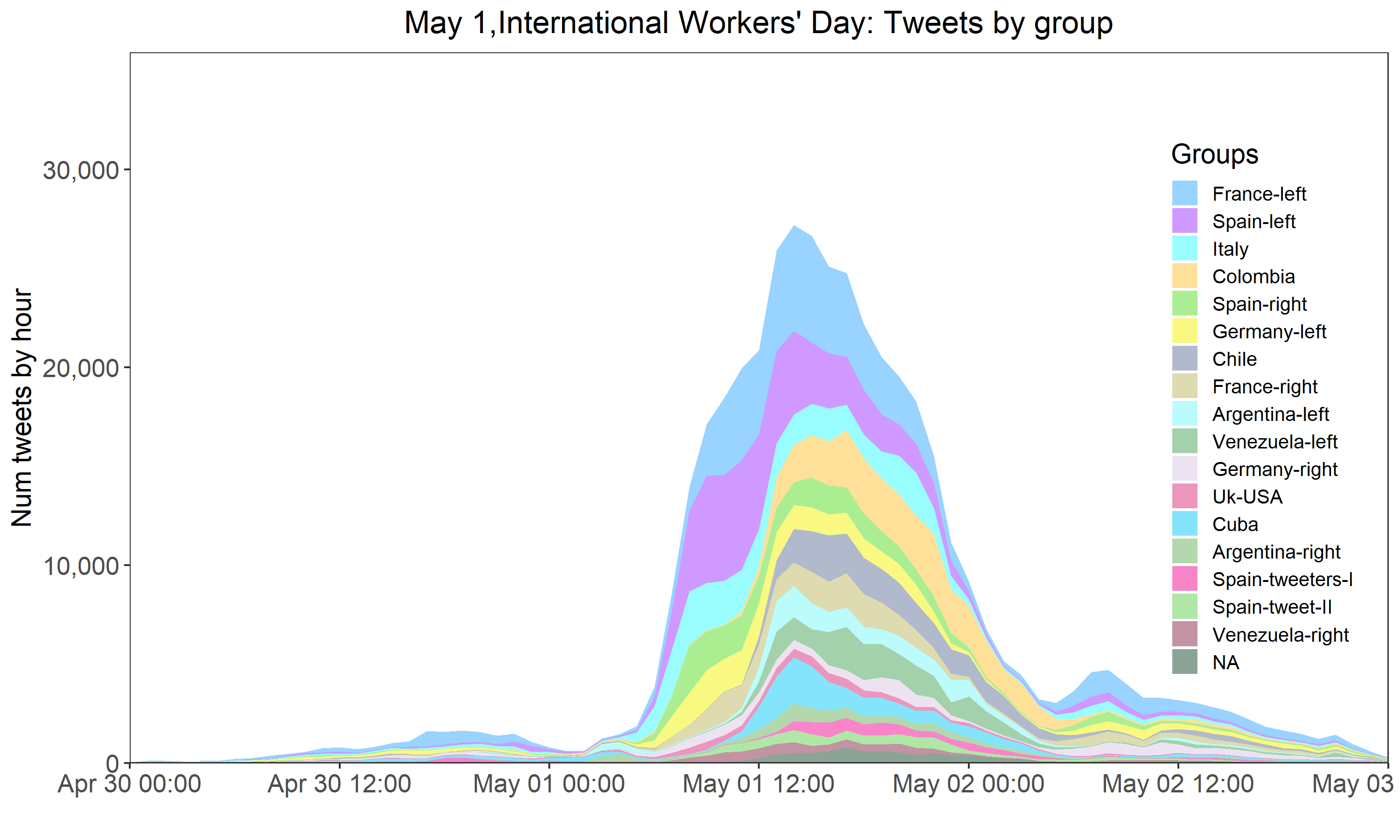

The participation of the different groups can also be seen in Figure 2, which shows the time differences between countries. The American countries began their activity at 13:00 (GMT).

FIGURE 2. TWEETS BY GROUP

The presence of hashtags in tweets (Fig. 8) was concentrated on 1 May, with #1May being the most frequent hashtag, followed by #DiaDelTrabajador. As the tags are associated with countries, time zones are also visible. As noted above, the volume of untagged content is not counted because of sampling difficulties.

FIG. 8 PRESENCE OF HASHTAGS IN TWEETS

Content analysis

Among the ten most prominent content items delimited by these tags, we identify a predominance of Spanish (nine of the ten). There is once again a considerable presence of political leaders from the Spanish left, represented by Podemos, including the Minister for Labour Yolanda Díaz and the former vice-president of the government and still leader of the party, Pablo Iglesias – who took advantage of the occasion in electoral terms due to the proximity of the electoral contest in the community of Madrid.

However, they likewise included those who took the chance to criticise the minister’s handling of the labour crisis resulting from the pandemic through a right-wing parody account that achieved considerable dissemination (6th most disseminated tweet).

We can also highlight the widespread protests in France against the Macron government’s reforms. The trade union response on May Day was visible and far-reaching. In Italy, meanwhile, news of the death of a female employee was disseminated on numerous occasions to denounce current working conditions.

Among English-language trends, the most popular tweet was one detailing labour improvements achieved through the trade union struggle. In fact, among all the content throughout the communities, we notice a generalised impact from commemorating the labour movement in all languages. This is probably the most interesting phenomenon in terms of memory: the ongoing impact of historical references to the labour movement that likewise occur in the networks. The Chicago martyrs feature prominently, although each country has also taken references from its own history. For example: in Argentina, Peronism; in Cuba, the memory of the revolution; and in Venezuela, Chavezism. This celebration is undoubtedly the one that most evokes its past to interpret its present.

Meanwhile, the strike in Colombia had a notable national and international impact on the day. Police repression of students and workers by the government prompted a protest movement that culminated in a national strike on May Day. Known as ‘Primero de Mayo’, it had symbolic significance. These protests also had a strong memorial nature on the web, looking at the relationship between the labour movement, protests and international solidarity.

Europe Day

Europe Day is one of the most relevant days in this study. Its results are providing us with highly relevant data on memory conflicts in the network and on the uses of the past in the present. As an example, in the latest issue of the European Observatory on Memories magazine, Observing Memories, we dedicated an article to this so as to explain the project through this specific case. Europe Day is a celebration that in practice increases both long- and short-term political tensions on the continent.[30] The creation of a European national identity has its point of conflict precisely in this commemoration, in which Eurosceptics and pro-Europeans fight over the political space and the narrative concerning the construction of Europe, its function, its limits and its implications. The celebration takes place every 9 May, in memory of the Schuman Declaration. Robert Schuman, the French foreign minister in 1950, took the first step towards integrating European states by proposing that the coal and steel of Germany and France (as well as any other countries that joined) should be subject to joint administration. This led to the creation of the first European community – the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) – forerunner of today’s European Union.[31] This is the third year it has been sampled, so we now have a broad comparative base.

Data file

| Collection method | Search API | |

| Collection period | 7–10 May 2021 | |

| Words searched | #DiaDeEuropa,

#DíaDeEuropa, #DiadEuropa2020, #9deMayoDíaDeEuropa, #FelizDíaDeEuropa, #EuropeDay2020, #EuropeDay, #Europatag, #diadaeuropa, #fetedeleurope, #JourneeDelEurope,

|

|

| Number of tweets obtained | 21,085 | |

| Number of tweets + RTs | 114,531 |

Evolution of participation

The evolution of activity around Europe Day on Twitter peaked on the 70th anniversary of the Schuman Declaration in 2020. The number of tweets in 2019 and 2021 was similar, with a lower impact.

The percentage of RTs to original tweets has been increasing year upon year. Likewise, the number of unique participating users also declined from 2020 to 2021.

Table 1:Evolution of participation

| Year | Original tweets | Tweets + RTs | % of RTs | Unique users |

| 2019 | 24,222 | 114,447 | 78.83% | 42,784 |

| 2020 | 44,929 | 218,149 | 79.40% | 100,163 |

| 2021 | 21,085 | 114,531 | 81.59% | 54,479 |

Analysis of the graphs

The profiles belonging to the giant component (the largest sub-graph whose nodes are all connected) were analysed to produce the final graph. (Graph 1). With this criterion, the percentage of profiles included is 91.55%. Among them, dissemination was widely dispersed, with almost 36.89% of profiles belonging to isolated groups or containing less than 2% of participants. Within the graph, the communities are also highly fragmented, the largest being the European Commission, containing 13.56% of profiles. The other groups contain less than 10% of users.

GRAPH 1. TWEET DISSEMINATION BY COMMUNITY

Graph 1 shows that as in 2019 and 2020,[32] there is a central area having the European Commission as its radiating centre and several branches corresponding to EU countries. Among these, institutional and pro-European messages predominate. The largest group, in fact, is made up of British pro-Europeans (9.93%) – who once again took the opportunity to show their rejection of Brexit. It is worth highlighting Spain’s participation in the celebration and the structuring of its dissemination clearly segmented by political parties: Partido Popular (4.59%), PSOE (4.47%), Podemos (4.31%), Ciudadanos (2.23%) and Catalan parties (2.17%). On this occasion, Italy and Germany did not form a group of more than 2% of users, as was the case last year. The main surprises to appear were a pro-refugee group (2.15%) and a community of Spanish interim civil servants protesting about their working conditions (2.1%). The breach between ideological extremes is, once again, clear. This is especially notable in France, where there is a high polarisation between pro-Europeans (6.1%) and Eurosceptics (2.8%). In 2019 and 2020, this divide already existed in France, which grew from 2019 to 2020 and decreased slightly in 2021 – probably due to increased activity on the Schuman Declaration’s 70th anniversary in 2020 (see Graph 2 for 2020). It is worth noting that this ideological separation is not so pronounced along the traditional left/right divide. While there is certainly greater capitalisation of Euroscepticism on the right, there is also a critical left – for example, the pro-refugee group – situated on the critical axis.

GRAPH 2. TWEET DISSEMINATION BY COMMUNITY IN 2020

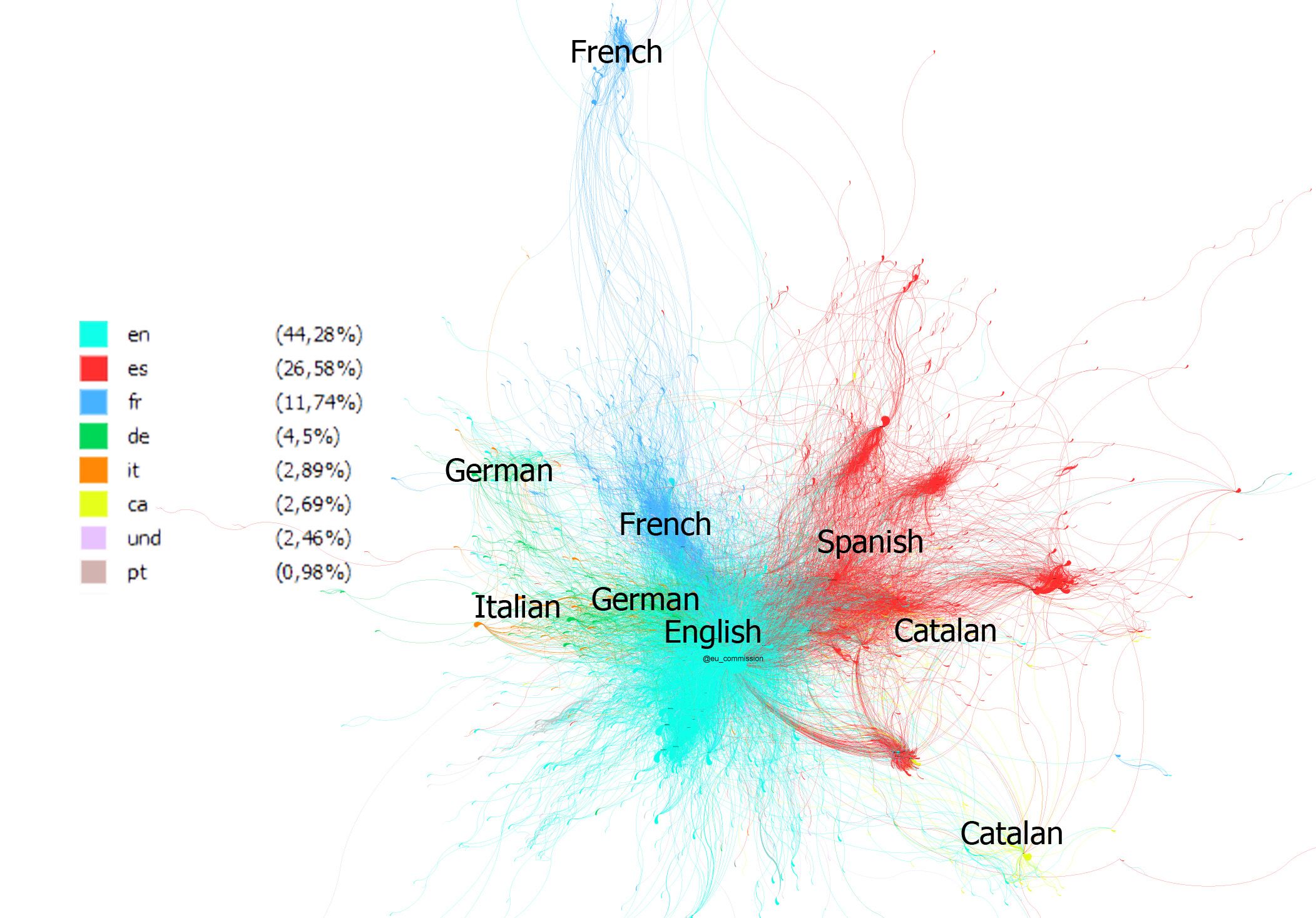

This polarisation is much more evident in language distribution. In this commemoration – as was the case in 2019 and 2020 – the graph is not so determined by users’ geographical or linguistic affiliations, while fragmentation for ideological reasons predominates, especially among French speakers (see Graph 3). In the final composition of the language analysis, English predominated at 44.28% (as opposed to 41.88% in 2020), used by British pro-Europeans and groups closer to the European Commission. The second language used was Spanish at 26.58% (compared to 25.37% in 2020), used by all Spanish political parties except the Catalan parties. The third language was French at 11.74% (10.43% in 2020); German was fourth at 4.5% (5.8% in 2020) and fifth was Italian at 2.89% (5.03% in 2020).[33] Catalan was present in 2.69% of messages (1.92% in 2020).

FIG. 3 GRAPH OF RTS BY LANGUAGE

In terms of the content creation medium, most tweets included hashtags (Graph 4). This was a consequence of the search undertaken where untagged keywords were not included due to the high possibility of false positives. However, despite the fact that the search terms were hashtags only, Twitter provided 30.76% of messages without hashtags. Therefore, taking into account that the impact was probably higher, we can conclude that there were narratives both associated with hashtags and ‘free’ in similar proportions. However, for our study we are much more interested in the phenomenon of hashtags, as they constitute a tangible, continuous space for the construction of memorial narratives. The most frequent hashtag was #EuropeDay, present in 25.59% of tweets (32.33% in 2020). In Spain, the most commonly used tags were divided by whether or not the word ‘Día’ was marked with a diacritic. The option with no diacritic #DiaDeEuropa prevailed (4.8%) compared to the option including the diacritic #DíaDeEuropa (4.67%). In France #Journedelaeurope with 2.01% (2.79% in 2020) and in Germany #Europatag 2% (2.78% in 2020).

GRAPH. 4 GRAPH OF RTS BY HASHTAGS

Temporary dissemination

An alternative view of the dissemination represented by graphs is the temporal evolution of the original tweets’ publication. The following graphs analyse the evolution over time of the publication of messages, both original and retweets.[34] In previous reports the graphs were created only around original tweets due to limitations of the viewing tool. In the 2021 reports, the tool was changed and the graphs will be constructed on the total number of tweets, as noted.

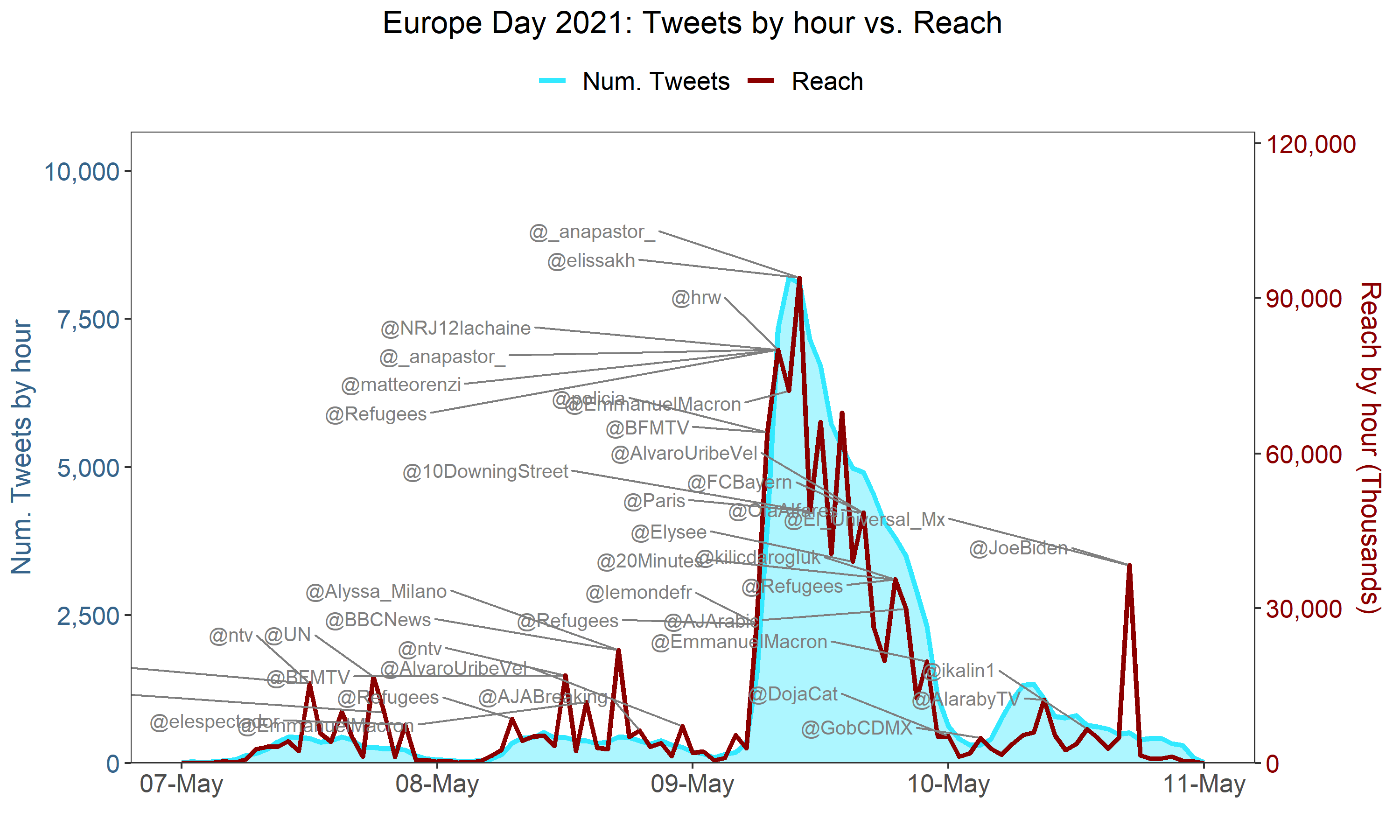

As is usual, intensity on the days before and after the celebration day was lower. The bulk of the tweets were concentrated on 9 May. The graph Fig. 1 shows the ratio of tweets posted to RTs received in one-hour intervals. It is a graph with two scales: tweets from 0 to 1,887 (in 2020, from 0 to 4,269) and retweets from 0 to 6,390 (in 2020, from 0 to 20,968).

FIG. 1 TWEETS VS RETWEETS

The participation of relevant profiles is reflected in graph Fig. 2 which records profiles with more than two million followers who participated. Most of them were institutions and media. The double-scale graph shows the relationship between the number of tweets posted in an hour, original tweets or RTs, and the possible reach. Reach is calculated as the sum of the followers of those who posted in each hour.

FIG. 2 PARTICIPATION VS REACH

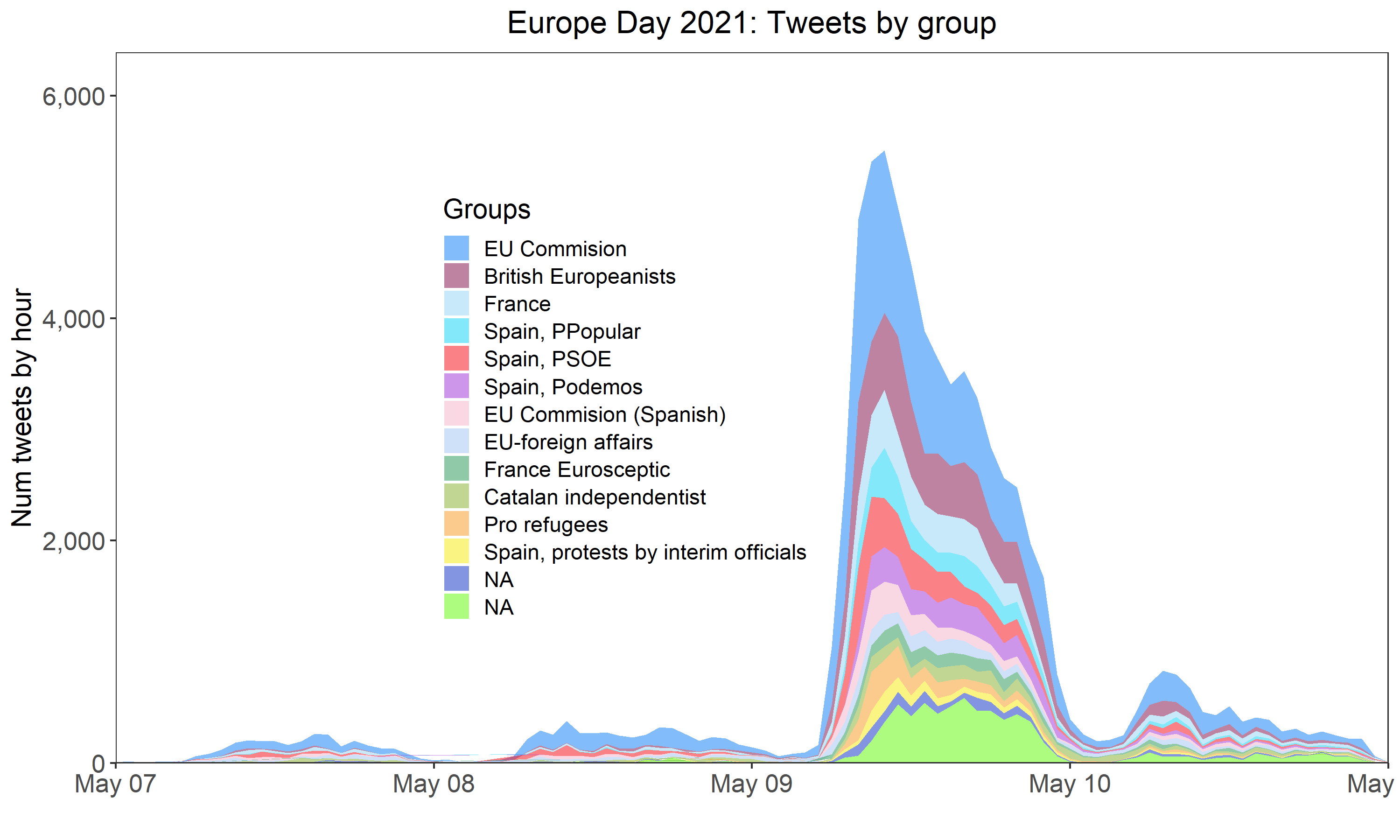

The participation of the different communities or groups is shown in Figure 3, which is fairly symmetrically placed in terms of time distribution. This is because most of the content was generated during European hours (peak time at 9:00 GMT), with little from the Americas. It is clear that Europe Day is very much a continent-wide celebration, with little impact abroad.

FIG. 3 TWEETS BY GROUP

Lastly, Fig. 4 shows the presence of hashtags in tweets . That is, the time distribution associated with each hashtag and its volume. In this regard, the most frequent hashtag was #EuropeDay, followed by #DiaDeEuropa. In this graph, furthermore, we can place the volume of tweets without an associated hashtag – which we suspect was even higher – comparatively. Untagged content, however, does not form a homogeneous community and was not included in the analysis.

FIG. 4 PRESENCE OF HASHTAGS IN TWEETS

Content analysis

The most widely disseminated message is from the European Commission, referring to the Schuman Declaration. In fact, the ten most popular messages of the day have a strong institutional content, all of them sent by prominent members of the political arena: number 2, from the President of the Autonomous Government of Madrid, Isabel Díaz Ayuso; number 3, from Seb Dance, a British Labour politician; number 4, from Yolanda Díaz, Spain’s Minister for Labour; number 5 from Angus Robertson, Member of the Scottish Parliament; number 6 from Terry Reintke, Member of the European Parliament; number 7 from Ian Blackford, also a Member of the Scottish Parliament; number 8 from Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission; number 9 from Carles Puigdemont, former President of the Autonomous Government of Catalonia; and number 10 from Irene Montero, Spain’s Minister for Equality. All these messages could be categorised as pro-European, albeit with some critical political messages – in a reformist vein – especially from the Podemos camp. The occasion was also used to launch political messages from the party agenda, for example; the Scottish camp calling for a new independence referendum, anti-Brexit campaigners showing their pro-European stance, or the Commission President announcing the EU’s NextGeneration programme, as part of the COVID recovery programme.

Among the Eurosceptic messages, we highlight those of the French community, with slogans that are clearly in favour of a French exit from the Union, the so-called Frexit movement. In fact, in this environment, very much occupied by the right, platforms such as those of ‘Generation Frexit’ have been set up, making their content more dynamic by the use of audiovisual materials and arguments throughout the day.

Meanwhile, we should position the so-called Euro-critics. Normally, unlike the Eurosceptics, this current is more hegemonic among the left, with a critical stance towards Europe, but aiming for reform rather than to challenge it. Interestingly, this year the most common theme used to represent these positions was the EU’s refugee reception policy.

As on previous occasions, we see that Europe Day draws together a number of diverse phenomena. The first is that it is a celebration without a tradition and of an institutional nature, while there is little social interest and it is heavily promoted in the networks by political representatives aspiring to strengthen the European identity. Secondly, it is a date when the EU’s current political conflicts collide – the COVID crisis, refugee policy and Euroscepticism, among others – making it a potential social thermometer. Lastly, at the memorial level, there is little evocation of the celebration’s origin (just over 800 tweets and RTs mentioned the Schuman Declaration). It is used with more presentist than memorial aims. Nevertheless, the interest in following the evolution of the consolidation (or failure) of a celebration is of enormous interest. It is similar to 23 August (a day to commemorate the victims of totalitarian regimes), in the work on commemorations and their uses. The past is a battlefield of the present – and no less so on the Internet.