At the last stage of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), General Franco’s coup army concluded the occupation of Catalonia on February 10th, 1939. Seeing the Francoist advance, over 450,000 Spanish republicans fled during the winter across the border into French territory. That massive exile was known as la Retirada (the Retreat). A few months before in France, precisely on November the 12th 1938, the government of Édouard Daladier approved a Decree-Law allowing the internment of “undesirable foreigners” under permanent surveillance. This law became the legal framework in which the French government later on imprisoned some 350,000 exiled Spanish Republicans in different rashly built concentration camps, many of them in the Roussillon area.

[Click on the image to see the complete album on Flickr]

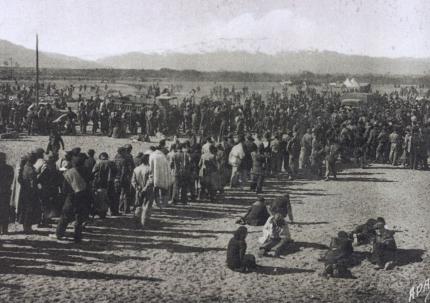

The refugee camp of Argelès was the first one to be set up for civilians in France. The chosen location was a piece of land of 100 ha along the coastline, and its building started only a few days before the French authorities opened the borders. On March the 1st 1939, 74,000 people including civilians and soldiers found themselves locked up in a huge, deserted beach area encircled by a barbed-wire fence and supervised by colonial troops of the French navy. The lack of lodging structures, as well as unsafe water supply and food scarcity, added to the exiled people’s poor health conditions caused the spreading of several diseases that, in turn, led to a dramatic increase in mortality among refugees.

When the Second World War broke out, “enemy residents”, foreign Jews, and political refugees (especially German and Austrian) were also brought to the camp. Later on, already under the collaborationist Vichy regime, a specific sector for Jews was set up, even though –until then– the only distinction was made between civilians and soldiers. The number of Spanish republicans dropped progressively due to the pressures exerted in order to force their repatriation or enrolment in the Foreign Workers Companies, or in the Regiments in Motion of Voluntary Foreigners. In March 1941 there were around 14,000 prisoners in Argelès. They were progressively transferred to more recent camps, such as Rivesaltes or Barcarès. At the end of July the camp started being dismantled, and in December 1941 it was closed down.

A long way has been travelled in the memorial field in Argelès from the first steps taken in the camp’s old cemetery –known as “the Spaniards’ cemetery”– until the recent opening of the Exile and Retreat Interpretation and Documentation Centre (CIDER) promoted by the town council. Relatives of the exiled people have played a key role in this progress. They are deeply aware that the memories they had received constitute a legacy which is loaded with values that go far beyond their collective. Thanks to their effort, the memory of the Spanish Republican exile will be saved and projected to the future as an instrument supporting the critical spirit without which a genuine exercise of democracy is not possible.