The Gonars concentration camp was located in the town of Gonars, in the province of Udine in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, in the northeast of Italy, near the border with modern-day Slovenia. The region has been a hub for much interaction and exchange between the two cultures for centuries. Although technically on Italian soil, the area was and is a blend of both ethnic Italians and ethnic Slavs as a result of its vicinity to a historically contested border.

As the largest Fascist internment camp on the peninsula, its construction was ordered by the Ministry of the Interior in 1941 and operated from October 1941 to 19 October 1943. Between 1941 and 1942, the camp held 600 Russian soldiers, several Russian commanders, and later, about a thousand Yugoslavian army officers and petty officers. The camp commandants were Lieutenant Colonel Eugenio Vicedomini, Cesare Marioni, Ignazio Fragapane, Gustavo De Dominicis, and Arturo Macchi.

Italian Concentration Camp for Yugoslavian Civilians Gonars http://gonarsmemorial.eu. Attribution: worraworra.

From 1 December 1942 – 14 September 1943, under the command of Gustavo De Dominicis, Gonars received the expressed purpose to gather together and intern Yugoslavian civilians. It housed anywhere from 5,100 to 6,500 individuals in wooden barracks, although the total number of internees to pass through the camp is estimated to be higher. It was divided in two sectors. Sector “A” was ‘repressive’ and Sector “B” was ‘protective’ for women and children.[1] There was no reported communication between the two sectors and they were distant from each other. Although some internees were given work responsibilities in the kitchen and medical barrack, only voluntarily and with their explicit consent, Gonars was not a work camp but a camp for internment.

A letter from the camp’s doctor, Mario Cordaro, divides the conditions at Gonars into two distinct categories: before and after the arrival of interned civilians. He describes the conditions as decent and in accordance with the Geneva Conventions. Once interned civilians begin arriving, however, Cordaro describes that the scene quickly becomes a “sad spectacle of misery and human degradation”.

Inmates, wooden barracks, guard towers in the background. Copyright: Muzej novejše zgodovine Slovenije. Museo nazionale di storia contemporanea, Slovenia

With the dissolution of the Gonars camp after the 8th of September 1943, internees were evacuated in groups of one hundred at a time with the intention of keeping them from falling into the hands of the Nazi Germany, now the enemy of Italy. In this manner, the camp was emptied in six days apart from a few ill individuals who were being cared for by a chaplain, Father Bianco, and taken to a local kindergarten of the comune to recover. The Commander then left, because of his decision to liberate the internees and not collaborate in nazi-fascist crimes.[2]

In the coming months, the inhabitants of the town of Gonars dismantled the camp, using the materials for other constructions, such as a kindergarten. All that remains of Gonars camp today is a grassy field along a state highway without any marking or monument (“A lato della strada statale che dal Palmanova porta a Codroipo, dove esse sorgevano un tempo, rimase soltanto un prato erboso privo di qualisasi segno toponomatico o monumentale…”) (Un Campo Di Concentramento Fascista: Gonars 9).

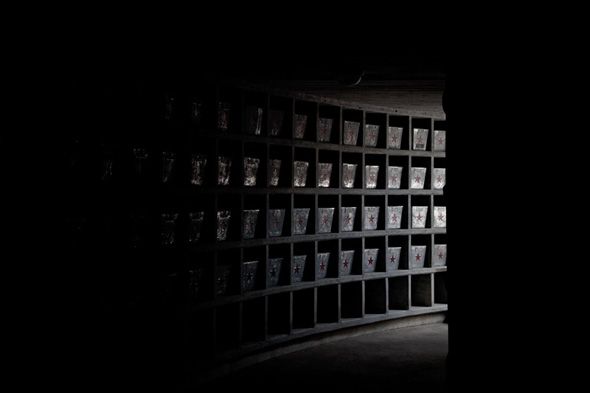

Through an initiative of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1973, Yugoslav sculptor Miodrag Živković created a flower-shaped monument with a red mosaic center at the local cemetery (15 miles northwest of the camp site), which holds two crypts with the remains of 453 Slovenian and Croatian citizens who where interned and died in the concentration camp.

Background information

Before Italian Fascism became a reality in 1922, anti-Slavic propaganda in Italy had already entered the public sphere. In a campaign seeped in irredentism, Italy attempted to reclaim areas of Yugoslavia as part of its lost homeland and to ‘rehabilitate’ the significant Italian populations living, for example, in Austrian Dalmatia. In accordance with the 1918 Armistice of Villa Giusti with Austria-Hungary after the end of World War I, the Kingdom of Italy annexed South Tyrol, Trieste, Gorizia, Istria and Udine. Race laws that demonized ethnic Slavs were enacted in an attempt to snazionalizzare (denationalize) the population and force cultural and ethnic assimilation. Civil liberties were restricted, surnames were Italianized, public demonstrations were made illegal, and the speaking of Slavic languages along the Julian March was banned.

With the rise of Fascism in Italy came the increased use of exile and internment to immobilize opposition and remove undesirables from society. This increased use of repression and the conditioning of Italians to become complacent towards the policies of the regime were only enabled because of the widespread use of violence at this time; violence became legitimized and accepted in the social sphere. Davide Rodogno, author of Fascism’s European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War, argues that to achieve this ethnic cleansing, anywhere from 100,000 to 150,000 ex-Yugoslavian civilians and prisoners of war alone were interned from 1941-1943. From Italy’s entry into World War II in June 1940 to the signing of the unconditional armistice in September 1943, there existed two types of civilian internment camps: those run by the Ministry of the Interior, and those established after early 1942 by the Regio Esercito.

The ethnic cleansing of ethnic Slavs and the Italianization of the area meant that the eventual internment of thousands of ex-Yugoslavian civilians was unsurprising, tracing its beginnings to at least two decades earlier. Mussolini was particularly hostile to the ‘Slavic race’ and he argued in a September 1920 speech that, “500,000 barbarian Slavs could be sacrificed for 50,000 Italians.”