Luís Farinha

Director of the Aljube Museum Resistance and Freedom

The Aljube Museum appeared four decades after the fall of the New State, as a result of an awakening from an apparent amnesia of an authoritarian regime that imposed censorship on the thought and creativity of millions of Portuguese people, that deported them and arrested them en masse and that sentenced them in apparently legal courts, founded on the most unacceptable precepts of a State, based on thousands of laws and diplomas, but which was never a Rule of Law. And which especially imposed on them, through the fear that stems from oppression, a silence and political indifference that tended to persist over time.

Without the combative attitude of groups of «memory-joggers», perhaps we would not have the Aljube Museum, as we can well understand today from the circumstances accompanying the possible conversion of the Peniche Fort Museum (to the north of Lisbon), into the National Museum of Resistance.

Why then this «silencing» of the memory of the resistance and, perhaps, of the Aljube Museum itself? Because this is a «Historic Museum» with strong political implications. The memories it awakens are a difficult and traumatic heritage that, even today, cause social, cultural and ideological tensions. In a certain sense, the object of the Museum is also the portrayal/reconstitution of an unfinished historical process. But also memories that generate silence because they prolong the «silence» imposed (and complied with) during the previous regime: the «New State», long and drab, had created an enormous national «political consensus», along with some international support, especially after World War II. Except for more unstable and dynamic historic contexts (during Mudismo – 1945, Delgadismo -1958, or with the ascent of thought and growing anticolonial struggle and the trade union movement, towards the end of the regime – 1970/1974), antifascism is a phenomenon of active minorities in the urban world and of some industrial and peasant sectors, which was manifested intensely in particular (short-lived) historic periods.

There is, therefore, an historic, cultural and political context that favours (has favoured) this silencing – or the «erasure of memory», as the groups of «memory-joggers» and many of the antifascists who are still alive say.

A context that is very particularly justified by:

- A very generalised historic lack of culture (in spite of the scientific advances made in universities, civic debates and disclosure in the media); this lack of culture is reflected in a still reduced «historic intelligence» concerning what «Portuguese fascism» signified in historic and experiential terms, with the habitual assimilation of the «quietism» of the regime into a situation of security;

- An exonerating interpretation of «Portuguese fascism», measured by the comparative gauge of the brutal violence of totalitarianisms: in this perspective the political prisons, mass deportations and censorship would be nothing compared with the totalitarian barbarism that the 20th century witnessed in different historic contexts;

- The relativism installed after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the interpretative reading of «post-Sovietism»: the Aljube Museum or Peniche Fort would have been places for «dangerous revolutionaries», assimilated to communists and extremists, with the deliberate obscuration of all other antifascists (from different political fields) who were held in the political prisons of Salazarism;

- A pragmatic political interpretation and attitude regarding post-colonialism, with the silencing of the crimes of colonialism: the Portuguese people would have been a «good coloniser» and the colonial war a reasonable response to the competing interests that were expressed within the context of the «Cold War», intended to defend the interests of the indigenous populations and of the settlers living there. This attitude has justified an acknowledged desire not to admit historic mistakes, like the one that led to a devastating colonial war that was incomprehensible in the eyes of the civilised world and which was intensely expressed, for example, within the UN;

- A rudimentary and biased historic interpretation of the I Republic (which preceded the military dictatorship), as an ungovernable State to which the «New Order» would have provided a solution (in a clear interpretation justifying post-First War World events): presented with an ungovernable country under a democracy (or in a liberal regime), the only solution would have been the implantation of a military/national dictatorship;

- An overwhelming mass culture, which reduces time (all times) to the (apparently happy) present time, commanded by formal democracy and by control of the market and of consumption: in these circumstances «why awaken forgotten hells»?

- An inability to recognise the suffering of the victims, to rescue them from oblivion and work towards true reconciliation that is not only expressed by the weak rhetoric of the expression of «brotherly nations», (in the case of the former colonies; by forgetting the suffering of those who were tortured (their struggle is, commonly, seen as an individual act for which the community is not responsible, when one’s patriotism is not denied and one’s commitment is confused with foreign interests); by the exoneration of the torturers, as a kind of person who fulfils his functional State duties, without even taking into account the fundamental rights set out in the very Constitution of 1933.

This premature amnesia of the fascist dictatorship is a complex political, cultural and historic phenomenon that has to do, on the one hand, with the failure to assume the uncomfortable legacy of the Dictatorship by the new democratic regime and, on the other, with the silencing that resulted from the «consensus» that the regime managed to impose for long periods of relative political stability. An imposed «silence», that still today constitutes a kind of sanitary line of defence from the discomfort of the individual and collective historic conscience.

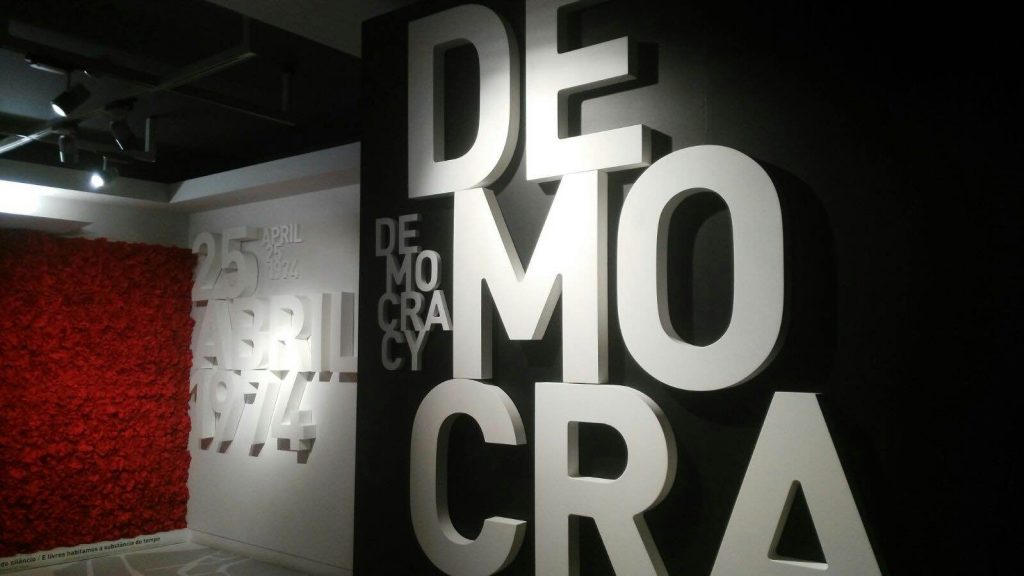

The founders of the Democratic and Social State believed that the improvement in the quality of life of the majority of the Portuguese would always drive away the «demons» of the past. However, the relative failure of this Social State showed how fallible and ephemeral the foundations of life are, which we naively believe last forever – and also the history that we (re)construct on top of them. «The only duty we owe to history – said Oscar Wilde one day – is to rewrite it» – in the dual meaning of rewriting what is reconstructed. It will have been for this reason that dozens of «memory-joggers», citizens and organizations alike, strove to reconstruct the Aljube Museum and today continue to fight for a National Museum of Resistance in Peniche Fort. In fact, Resolution no. 24/2008 (passed unanimously in the Assembly of the Republic) recommended the «creation of a museum of freedom and resistance in the historic centre of Lisbon», as a uniting factor of a network of museums established to evoke and value the struggle and resistance of thousands of men and women who, since the implantation of the military dictatorship, in 1926, fought for freedom and democracy – revolutionaries, reformists or simply advocates of the Rule of Law, violently dismantled as from 1926.

Two years after the opening of the Aljube Museum (in 2015), it is worthwhile taking a look at the reactions of some of the Museum’s 40 thousand visitors in this period: «When I was 18 years old I used to work down from here, in Pathé Films. I’d walk along the side of the prison. I knew that «bad things» went on here, but I tried to ignore it and walk on the other side of the street. We all did the same, you understand? Today I think that I wasn’t very brave at that time. You know… we tried not to know – and to forget». Today, this man is over 70 years old and is a student in a Third Age University in Peniche – a city to the North of Lisbon.

It is, therefore, an uncomfortable, silenced and often traumatic heritage that we speak about in the Aljube Museum. The Museum does not have a collection – and not even a prisoner entry register, because it is still missing. As this place has been turned into a museum, it lives especially from the immaterial heritage that has been reconstructed using police records, the court records and especially those of some of the around 30 thousand political prisoners, (many of whom are still alive), who were held there. In fact, as the prison was closed in 1965, a large part of its «prison records and repressive contents» disappeared, as a result of abandonment or the banalization that resulted from the daily activities inherent to its subsequent use as a building of the Ministry of Justice, with multiple administrative functions.

It is, therefore, a Museum that resorts to the first-hand memory of those who passed through it and which uses History as a resource of validation and of reflection on what it meant to be a political prisoner during the dictatorship: on the reasons why someone was imprisoned, on the methods of the police and political courts, using long preventive custodies and torture to extract the «truth», on the (lack) of reaction by society, in general, on the mishaps committed by justice and, especially, on the negative outcomes of these prisons on the private, professional and family life of those who dared to fight the lack of political and social rights. The latter is, without doubt, one of the museum’s main missions: to rescue the wounded memory of the combatants, all of whom were marked as «dangerous» for a regime and for a society where there tended to be an oppressive and tendentially consensual silence, especially during some of the more stable periods of the dictatorial regime. For many opponents it was a fight on two fronts: against the dictatorial State on the one hand and, on the other, against the indifference of a significant part of people who, only very late on became aware of the harm of isolationism, conservatism, the lack of liberties and the impossibility of assuming public positions in cases as calamitous as those that occurred in the course of the long colonial war.

We are therefore speaking of controversial memories – almost as contentious as the facts and reasons that gave rise to them at the time because, in a way, the transition to democracy is still (and perhaps is always) an unfinished process. As a Museum that focusses on historic content – showing the absence of rights and the struggle to obtain them in specific and concrete situations of contemporary Portuguese history, it is also a Museum with a strong political component, where the approach to the topics and their interpretation requires a multifaceted intervention/mediation. Not only to see history in a plural way, but to foster a critical view of the world today. Today we know that our grandparents – many of whom lived through the hell of the years that followed the end of War World I, and who participated in the implantation of a «good dictatorship against bad politicians» in 1926, did not imagine that the 48 following years would be under a dictatorship. We also know that many of the Germans who elected Hitler could never have imagined what would later be the Holocaust.

We are, therefore, better informed. But are we really, or is the mass culture that is imposed on us and distracts us preparing to betray us? There are many signs of backtracking from the «enlightened heritage», both in the world and in «civilised» Europe: yesterday and today, egoistic forms of nationalism are always ready to appear to exclude the «other»: it is no longer the communist, the freemason or the Semite. Other «names» will appear, because we are good at nominating the enemy.

Looking at the present day in Portugal and in the world – this is the Aljube Museum’s other fundamental mission. The History of the Dictatorship and of the New State can never be a chest of curiosities from which we nostalgically pluck out «stories of life», like a voyeur or with literary and artistic intent. The heroism (and also the weakness, of certain moments) of those who fought for Freedom helps us to understand how one fights, how one gives up and how the struggle for Democracy and for equality for the many requires us to keep a watchful eye on these major moments of History’s «return» to times that we thought impossible, after achieving heights of civilization of which we can be proud.

In the Aljube we favour mediation with the groups that visit us – fostering dialogue (and even reconciliation with the more traumatic memories of many of those who visit us). We encourage the public hearing of testimonies of combatants, we choose special moments of struggle (individual and collective) as spaces to commemorate freedom, we gather objects and memories to make them known in our Documentation Centre – to students, to scholars -, and we invite specialists (national and foreign) to debate lesser known or controversial aspects of the history of the Portuguese authoritarian state and its transition to democracy.

The future of the Aljube Museum will be, most certainly, what its visitors – represented by an Advisory Board – define as what is most important and valuable. While we are able, the Museum will always be a place of dialogue that helps to prepare «future presents» of freedom and democracy.