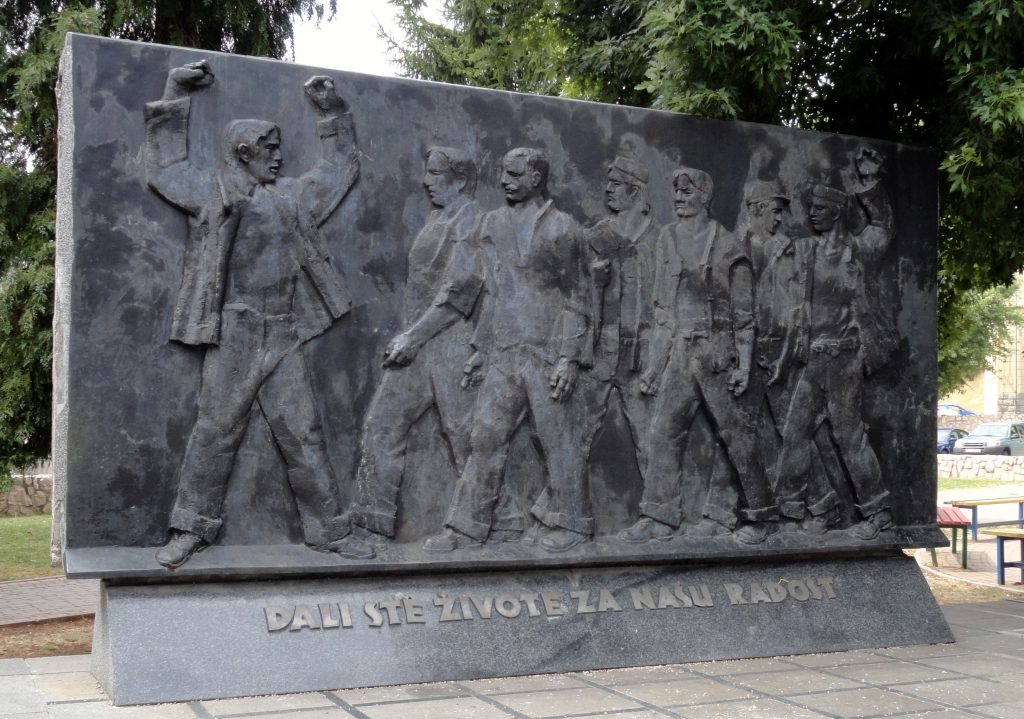

Picture: Unveiling the monument to Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish Civil War in the Rijeka barracks in 1977 | Archive of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Čedo Kapor collection.

Vjeran Pavlaković

Associate Professor, Department of Cultural Studies, University of Rijeka

In June 2019, I was in the state archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo, digging through a totally disorganized box of photographs, when I found the image that had been eluding me for years. It was in the collection of Čedo Kapor, a Spanish Civil War veteran from Trebinje who later rose to prominence in the Partisan movement during the Second World War and held numerous political positions in Tito’s Yugoslavia. The photos were piled up inside a box, with pictures from the Gurs internment camp in southern France mixed in with photographs of Partisans marching through the harsh Herzegovinian landscape and ribbon-cutting events with communist party dignitaries in the 1970s. A number of images in the collection included the unveiling of various monuments, but one caught my eye. The monument featured a shirtless Partisan defiantly striding forward with a raised fist, an archetypal figurative depiction of the Yugoslav resistance movement that can be found on monuments throughout the former Yugoslavia. But what was different was the inscription on the base, written in Spanish: No pasarán. Behind the dignitaries and soldiers in the photograph I noticed a striking building, currently the Academy of Applied Arts at the University of Rijeka campus, but once the command centre of the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) barracks located on Trsat hill in Rijeka, Croatia. Until 1991, the barracks were named after the nearly 2,000 volunteers from Yugoslavia who had fought to defend the Republic in the Spanish Civil War. [2]

During the Croatian War of Independence, the Croatian Army and military police had occupied the barracks, which were then handed over to the city of Rijeka and finally transformed into the university campus that opened in 2011. Since then I have heard rumours that a monument to the Spanish Civil War had once been located on the site of the former barracks, but the building of the campus had completely changed the landscape and all my efforts to track down information on the possible existence of a monument were fruitless. For some years I had been discussing putting together an exhibition on Yugoslav monuments to the Spanish Civil War with Oriol López Badell, from the European Observatory on Memories, and the inability to find reliable information on the Rijeka monument had frustrated me even as the preparations for the exhibition moved forward for 2020 when Rijeka was to be the European Capital of Culture. But spotting that single image in a box of photographs brought my search of nearly a decade to an end and gave the final impetus for completing the exhibition.

The story of this one monument is an apt anecdote for describing the relationship of contemporary Croatia and the memory of volunteers who fought in the Spanish Civil War: we can say that there is more collective amnesia than collective remembrance. The exhibition “Cultural Memory and the Spanish Civil War” (Kultura sjećanja i Španjolski građanski rat), [3] organized as part of the Rijeka 2020: European Capital of Culture programme, sought to break through the fog of forgetfulness and engage the public in a dialogue about this important part of not only the history of Rijeka, but the history of Croatia, the former Yugoslavia, and above all, Europe. According to the meticulous research by French historian Hervé Lemesle, 1,910 volunteers from the former Yugoslavia had fought on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War, with approximately half coming from Croatia. While many were communists or were recruited by communist parties in Europe and North America, around half had no political affiliation and fought in Spain because they saw defending the democratically elected government against fascism as an opportunity to fight against injustice and express international solidarity with the Spanish people.

This exhibition did not seek to glorify war or offer an ideological interpretation of the past, but rather to acknowledge the sacrifice of individuals who travelled to an unknown country to defend democratic and humanist values in a turbulent age characterized by the rise of fascism. The values of peace, dialogue, tolerance, and international solidarity are those that need to be reflected upon, 80 years after the Nationalists proclaimed victory and implemented a brutal dictatorship that lasted over 35 years. Rijeka2020 is an opportunity to place Rijeka within the broader context of European events in the twentieth century, and the Spanish Civil War was that moment when one country inspired artists, writers, activists, workers, and antifascists from around the world to rally around the cause of democracy. Although the cultural memory of the Spanish Civil War in Croatia has faded over the past 30 years, the exhibition sought to spark a new understanding of this conflict and the lessons we can draw from it in order to not repeat the mistakes of the past. Moreover, the exhibition’s reflection on memory politics more broadly was intended to draw attention to the fact that other aspects of Croatia’s antifascist past have been deliberately erased from public space and collective memory since the disintegration of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. While it is not surprising that new historical narratives would merge in the wake of Croatia’s War of Independence (Domovinski rat, 1991-1995), it is problematic that Croatia’s antifascist heritage of the twentieth century was subject to nationalist revisionism that sought to rehabilitate Nazi-fascist collaborators, the Ustaša regime, as a counterweight to the Partisan movement of the Second World War. Reactions to this exhibition, along with the work of many civic organizations in Croatia over the past decade, indicate that despite the rise of populism, extreme nationalism, xenophobia, and radical-right groups across Europe, many segments of Croatian society continue to nurture the antifascist values necessary to foster an open and tolerant society in the twenty-first century.

This is particularly relevant for Rijeka and the Croatian Littoral (Primorje), since one of the mottos of Rijeka2020 is the “Port of Diversity”. The exhibition listed over one hundred names of volunteers from Rijeka and the surrounding region, a testament to the antifascist sentiment of this part of Croatia that arose due to the experience with Italian fascism in the 1920s and the even greater deprivations of the Second World War. Most of the volunteers fought in the International Brigades, and nearly half lost their lives in distant Spain. Those that survived had to endure internment camps in France and Germany as well as difficult journeys back home, where several hundred of them joined the Partisan movement. The Spanish volunteers from Yugoslavia, known as naši Španci (Our Spaniards), were particularly valued because of their military experience and ideological discipline, which was invaluable during the first year of the antifascist

uprising. The exhibition was the result of new research conducted in archives in Croatia, BosniaHerzegovina, and Serbia, contributions from scholars participating in a conference held at the University of Rijeka in June 2019 (including participants from EUROM, the University of Barcelona, and the Pavelló de la República Library), and local history students. [4 ] Two panels focused on the contribution of women in the Spanish Civil War, including short biographies of the sixteen women from Yugoslavia who primarily served in the medical corps. A panel on anarchists from Yugoslavia who fought outside the International Brigades highlighted the fact that their participation remains largely under-researched, since many of them were Italian-speakers from the region of Istria and were generally ignored by communist historiography. Another topic which unfortunately was not covered in this exhibition but awaits the efforts of new scholars is the participation of Istrians in Franco’s forces, either as Italian volunteers [5] or Slavs who were mobilized to fight in Spain against their will. [6]

The exhibition included the personal biographies of two volunteers from the Croatian Littoral – Edo Jardas, who served as Rijeka’s mayor in the 1950s, and Vladimir Ćopić, the highestranking Yugoslav commander in the International Brigades. Eduard “Edo” Jardas (1901-1980) was born in Zamet, now a neighbourhood of Rijeka, and became a communist a few years after he emigrated to Canada in 1926. He was initially involved in organizing forestry and mine workers into communist-run unions and became the editor of Borba, a Croatian-language Party newspaper. He arrived in Spain in late March 1937, where he commanded a machine-gun unit for the Dimitrov Battalion and the Third Company of the LincolnWashington Battalion. He was wounded twice, the second time so severely that he needed to be evacuated to France. In 1938 Jardas returned to Canada, where he became a member of the Central Committee of the Canadian Communist Party and continued his publishing activities. After the Tito-Stalin split in 1948, Jardas returned to Rijeka on the ship Radnik (“Worker”), which had been commissioned to ferry returnees to Yugoslavia after the Second World War. After serving in the Yugoslav embassy in India, he was Rijeka’s mayor (president of the City People’s Council) from 1951 until 1959, as well as a member of the Central Committee of both League of Communists of Croatia (SKH) and Yugoslavia (SKJ). His personal collection in the Croatian State Archive in Rijeka contains not only considerable information on Yugoslav volunteers who had come from North America, but a great deal of material on the activities of the Spanish Civil War veterans’ organization which was very active in promoting the memory of the struggle against Franco.

Vladimir “Senjko” Ćopić (1891-1939) was the most famous revolutionary from the Croatian Littoral in the interwar period. He was born in Senj and studied law in Zagreb, but his studies were cut short by the outbreak of the First World War. As an Austro-Hungarian soldier, he was captured and sent to a Russian POW camp. Ćopić was not allowed to join the Yugoslav Volunteer Corps because he refused to swear an oath to the Serbian King Petar Karađorđević. As a result, he was not allowed out of the camp until the October Revolution, and soon after his release, he joined the Bolsheviks. In 1919, he returned to Yugoslavia to spread communist propaganda, and participated in the Party’s founding congress in Belgrade in April. He was immediately elected to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ), and after it was banned he was sentenced to two years in prison.

In 1925, he was forced to flee to the USSR, where he attended the International Lenin School for four years. Ćopić worked in Prague as a Comintern instructor to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and from 1932, together with Milan Gorkić and Blagoje Parović, de facto led the KPJ. After a conflict with Gorkić, Ćopić volunteered to go to Spain, where he arrived in January 1937. He became a political commissar and then the commander of the Fifteenth International Brigade, also known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. He led the brigade in the battles of Jarama and Brunete.

In the spring of 1938, he was singled out by Josip Broz Tito as one of only two intellectuals who should be considered for working in the party leadership (the other being Božidar Maslarić, another Spanish Civil War volunteer). Ćopić arrived in Moscow in late August 1938, roughly at the same time as Tito. The two comrades wrote reports for the Comintern on the condition of the party and plans for re-establishing its activity among the masses in Yugoslavia. However, the NKVD arrested Ćopić on 3 November 1938, and he was shot five months later. The Soviet Union rehabilitated him in 1958. In 1976, his hometown of Senj unveiled a bust of Ćopić, which is presumably stored in the Senj city museum after being removed from the square that bore his name until the 1990s.

The example of the missing monument from the Rijeka barracks and Ćopić’s removed bust are two examples of the broader issue of monuments in Croatia – not only their construction but also their destruction. In Croatia alone, around 3,000 out of 6,000 Partisan monuments and plaques were removed, destroyed, damaged, defaced, or transformed in the 1990s, only a few of which have been restored. The situation with monuments in other Yugoslav successor states varies, often depending on the intensity of the wars in the 1990s. Slovenia managed to preserve almost its entire mnemonic landscape of the Second World War, while Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina witnessed considerable destruction coupled with the erection of hundreds of new memorials to the more recent wars. [7]

The exhibition in Rijeka presented information on monuments to the Spanish Civil War that have been built around the world, particularly in Europe and North America, but also in the former Yugoslavia. While certain monuments were built to individual volunteers in the Spanish Civil War (such as Ćopić in Senj, Nikola Car “Crni” in Crikvenica, or Anton Rašpor in Klana, all towns on the Croatian Littoral), other monuments dedicated to the Second World War integrated Spanish fighters into the broader antifascist narrative, especially since many of the Španci who managed to return to Yugoslavia fought as Partisans. This means that many monuments referencing the Spanish Civil War have suffered the same fate as other Partisan monuments since the 1990s; they were destroyed, damaged, or removed.

Croatian Serb rebels in Korenica destroyed the monument to one of the most famous Spanish volunteers, Marko Orešković “Krntija”, because he symbolized cooperation between Croats and Serbs. The local government in Nevesinje (BosniaHerzegovina) moved the massive monument to Blagoje Parović to the outskirts of his hometown, even though the central square where he used to sit still bears his name. In the Croatian town of Plaški the bust of Robert Domany, a Jewish volunteer killed while leading a Partisan unit in 1942, was stolen along with several others in the 1990s and finally restored in 2016.

Although the majority of the monument destructions took place in the 1990s, the struggle to preserve the antifascist cultural heritage continues to this day. This is another reason why it was important that this exhibition should emphasize the value of transnational remembrance. When the local government attempted to remove the centrally located Partisan memorial and ossuary in the town of Perušić, activists and the Croatian antifascist association reacted to prevent the ongoing removal from the public space of those who fought against fascism. The monument is not just dedicated to fallen Partisans and civilian victims of fascist terror from Perušić, but includes names of twelve volunteers who died in Spain. Interestingly, two of the most vocal advocates for preserving the monument are veterans of the Croatian War of Independence, as noted in a recent article with the headline “They won’t give up their Spaniards” (Ne daju svoje Špance). [8] Although monuments of the 1990s war compete with antifascist memorials in public space and veterans’ organizations have been among the sharpest critics of memorializing the Partisans, this is an example of cooperation and evidence that the memory of all tragic conflicts of the twentieth century can be commemorated within the proper historical context.

The exhibition of cultural memory and the Spanish Civil War not only sought to provide information on the forgotten history of Yugoslav volunteers who fought for the Republic, but on many ongoing issues related to memory politics in both Croatia and Spain, as well as throughout Europe. After struggling with the legacy of Francoist memorials for decades, Spain is still building memorials to Republican forces or victims of Francoist terror that were denied under the dictatorship and the subsequent years of silence, in places such as Málaga or Fuentes de Andalucia. Last year’s decision to remove Franco’s body from the Valley of the Fallen was another reminder of how Spanish society is still coming to terms with the legacy of the Civil War, not to mention the still unresolved issue of thousands of victims who remain in unmarked mass graves. Croatia continues to seek a balance of investigating communist crimes and its own exhumations without completely succumbing to revisionist narratives that seek to erase all of the contributions of the Partisan movement, while simultaneously trying to create an inclusive commemorative culture for the Independence War in the 1990s. Rijeka2020, although greatly reduced

due to the global Covid-19 pandemic, nevertheless provides an opportunity to engage in a European dialogue about difficult pasts, and this exhibition is an example of a comparative approach in dealing with the legacies of war and dictatorships but also international solidarity and cooperation.

Footnotes

[1] This research was supported in part by the University of Rijeka under the project „Riječki krajobrazi sjećanja“ (unirihuman-18-273).

[2] Kasarna španskih dobrovoljaca (Barracks of the Spanish Volunteers).

[3] The exhibition was held on the University of Rijeka campus in January 2020 and in the pedestrian street Korzo in the centre of Rijeka in March 2020. It was displayed in Pula and is scheduled to be in Sarajevo (Bosnia – Herzegovina) later in 2021.

[4] Students created a website about the project as part of their research on the Spanish Civil War.

[5] A recently discovered document from the fascist administration in Pula (Pola) lists the names of five volunteers who died in Spain, indicating that there were many more volunteers who fought there and that there were many others from other parts of Italian-occupied Croatia and Slovenia.

[6] Since Istria and Rijeka were part of the Kingdom of Italy during the interwar period, Croats or Slovenes found guilty of various offences ranging from smuggling to nationalist activities were often sent to fight in Spain as an alternative to prison in the 1930s.

[7] For a sense of the amount of money spent on the building of new monuments in Bosnia-Herzegovina, see https://balkaninsight. com/2020/01/03/bosnia-spends-e2-million-on-divisive-warmemorials/.

[8] Novosti, 3 July 2020, https://www.portalnovosti.com/ne-dajusvoje-spance.