Hisayo Katsui, University of Helsinki

Cover picture: Teaching and articulation lesson of sound at the School for the Deaf in Turku (Archive of the Finnish Deaf History Society)

Background of the truth and reconciliation process

In June 2025, the Finnish government initiated a truth and reconciliation process with the deaf and sign language community and the Finnish Sign Language community. This type of process typically involves official apologies for past injustices committed by powerful institutions, such as the state, the church, or influential social and economic actors. One of the most well-known examples is the Truth and Reconciliation process addressing Apartheid in South Africa

This initiative is the first of its kind globally, in which a government officially acknowledges and addresses historical injustices experienced by a disability community. This article explores this groundbreaking effort by first outlining the preparation phase of the process, followed by a review of the identified historical injustices, and concludes with reflections on possible future directions.

It is widely recognized that the disability community has faced—and continues to face—injustices both in Finland and around the world. For decades, disability communities locally and globally have responded by empowering their members, raising public

awareness, and advocating for change among decision-makers. However, progress has been slow, and this lack of meaningful societal transformation has led many within the disability community to rethink their strategies for social change.

This truth and reconciliation process represents one such response—an effort by the deaf and sign language community in Finland to address these long-standing issues and seek a path toward justice and inclusion.

Two earlier truth and reconciliation processes in Finland helped pave the way for this development. One involved individuals who had been placed in foster care as children and suffered mistreatment. In 2016, the then Minister of Social Affairs and Health issued an official apology. The second process began in 2021 and involved the Sámi people—the only officially recognized Indigenous people in Europe—who launched their own truth and reconciliation process with the Finnish government.

Discussions about a similar process for the deaf and sign language community began in 2016, particularly within the board meetings of the Finnish Association of the Deaf (FAD). In 2018, a seminar brought together several minority groups, including Roma people, individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, Finnish Sign Language users, and Sámi representatives. Following this event, a deaf panelist was invited by Member of Parliament Timo Harakka—who is himself the child of deaf parents—to attend a meeting of the parliamentary sign language network. Representatives from FAD also participated.

After that meeting, the parliamentary sign language network began working on an initiative for a truth and reconciliation process. Around the same time, in 2019, FAD published a press release calling for an investigation and an official apology for the injustices experienced by deaf people. The Finnish Deaf History Society also voiced similar demands that year. In response, Timo Harakka publicly stated on social media that this issue must be addressed at the governmental level.

In 1905, deaf people decided to establish the Finnish Association of the Deaf (Archive of the Finnish Deaf History Society)

Later in 2019, the Finnish government under Prime Minister Antti Rinne announced in its program a commitment to launch a national reconciliation process addressing the human rights violations historically experienced by the deaf in Finland.

In 2020–2021, the Finnish government commissioned our research team to carry out a study titled Signed Memories. The aim was to investigate the historical injustices faced by the deaf and sign language community in Finland from 1900 to the present day.

The following sections are based on the findings of that study.

Historical and present injustices

The Finnish sign language community emerged in the mid-1800s, when Carl Oscar Malm established the first school for deaf people in Finland in 1846. Malm had studied in Sweden, where he received an education in sign language, and brought those methods back to Finland. For a time, sign language education flourished. However, by the late 1800s, it began to decline due to the rise of eugenic ideology, which heavily influenced education and social policy.

This ideology promoted oralism—the belief that deaf people should only use spoken language—while sign language was actively suppressed. As a result, sign language was banned in schools for deaf students from the late nineteenth century until the 1970s. This prolonged period of prohibition left deep and lasting harm—not only to deaf individuals and the sign language community, but also to Finnish society as a whole. It reinforced the idea that sign language and deaf culture were inferior to spoken language and mainstream culture. These stigmas, rooted in eugenics, continue to shape societal attitudes and contribute to intergenerational pain within the community.

The harm extended beyond language suppression. The deaf were also subjected to state policies that restricted their reproductive rights. Between the 1920s and the 1970s, eugenics-based legislation was enacted and enforced, including the Marriage Act (1929– 1969) and the Sterilization Act (1935–1970). These laws targeted people deemed “unfit for society,” such as persons with disabilities and the deaf, based on the belief that they would pass on undesirable traits to their children.

For example, deaf women were sometimes required to consent to sterilization in order to receive permission to marry. In addition, many deaf children and adults were subjected to forced rehabilitation programs and experimental medical procedures, sometimes without their informed consent. These policies caused not only psychological trauma, but also physical harm, leaving behind lasting, embodied scars. The legacy of these national laws and policies continues to affect the deaf and sign language community, shaping collective memory, identity, and trust in public institutions.

Today, it is estimated that there are between 4,000 and 5,000 users of Finnish Sign Language, and around 90 users of Finnish-Swedish Sign Language. The number of users of both sign languages is steadily declining. In addition to the long history of injustice, recent technological and educational developments have also contributed to this trend.

One major factor is the widespread adoption of cochlear implants. These implants have become a standard medical procedure for children born deaf. However, parents often are not informed about the option of a bilingual approach that includes sign language alongside spoken language. Many children with cochlear implants are therefore not introduced to sign language and grow up without access to the sign language community.

Another significant change has been the closure or merging of schools for the deaf. Instead of attending specialized schools, most deaf children now go to local mainstream schools. Only a few schools still offer Finnish Sign Language classes or bilingual education, and even these programs are limited.

The remaining sign language classes typically have very few deaf pupils and often include students with multiple disabilities and varied backgrounds. These schools generally do not actively recruit or encourage deaf pupils to enroll in their sign language programs.

In some municipalities, transportation services for deaf pupils have been cut. This has forced families to send their children to nearby schools that do not offer a sign language environment. Without accessible education in sign language, both the language and culture associated with it are further marginalized.

This situation poses a serious threat to the vitality of the sign language community. The lack of institutional support, combined with inadequate parental guidance and policy gaps, continues to weaken the linguistic and cultural foundation of the community.

Girls’ dormitory at the Porvoo school for the deaf around the 1900s (Archive of the Finnish Deaf History Society)

Current status of the truth and reconciliation process

Our study, Signed Memories, confirmed the serious historical injustices experienced by the deaf and sign language community in Finland. These injustices primarily concerned violations of linguistic and cultural rights, as well as reproductive health rights. These violations, in turn, had widespread impacts on other fundamental rights, including the rights to education, employment, and participation in cultural and social life.

In 2015, Finland took an important step by enacting the Sign Language Act, which aimed to protect the linguistic and cultural rights of the sign language community. The country’s sign language interpretation service is now considered one of the best in the world. However, despite these advancements, the legacy of eugenic ideology remains present in institutional structures and societal attitudes.

Following the publication of Signed Memories, the Finnish government commissioned a second study to assess the need for psychosocial support for the deaf and sign language community. This study aimed to help the community process past harms and move toward healing and justice. A working group was established to explore next steps. It included representatives from both community and government institutions.

As a result of this process and ongoing advocacy, the Finnish government officially acknowledged the injustices faced by the deaf and sign language community. In early June 2025, the government formally launched a truth and reconciliation process. This included the release of a mandate document and the appointment of a secretariat and steering group to oversee the process.

The secretariat, while housed under the Ministry of Justice, operates as an independent body. It has been tasked with establishing working groups, conducting further studies, and preparing a final report by the end of 2027. The steering group consists of representatives from five community organizations as well as a representative from the government.

To support the process, the government has allocated €1.8 million, with the process scheduled to run for two years. This marks a historic moment—not only for Finland but globally—as it is the first truth and reconciliation process in which a government officially addresses historical injustices against a disability community.

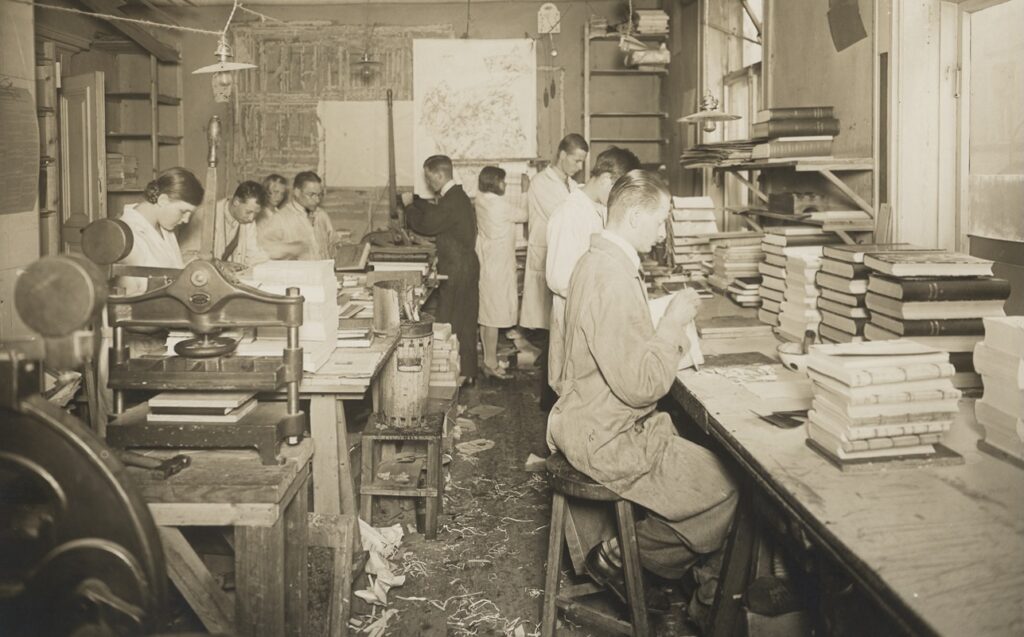

Oskar Wetzelliä’s printing house in the 1920s. Vocational training was provided in the house. (Source: Finnish Museum of the Deaf)

Discussion and concluding remarks

The success of the truth and reconciliation process requires more than just cooperation between the deaf and sign language community and the government—it also demands active engagement and genuine ownership of Finnish society as a whole. The ultimate goal is social transformation, ensuring that the injustices of the past are not repeated.

Globally, many governments have engaged in truth and reconciliation processes to address historical wrongs and rebuild trust with marginalized communities. When examining these international efforts, we can identify three general patterns or focuses: 1) past-oriented, 2) presentoriented, and 3) future-oriented processes.

In past-focused processes, the emphasis is on establishing a shared understanding of historical injustices. These processes often begin with thecollection of reliable evidence and testimonies, leading to official apologies grounded in truth agreed upon by both the affected community and the state.

The experiences of individuals who directly suffered the injustices are placed at the center.

Present-focused processes build on the recognition that historical injustices are not isolated in the past, but continue to shape current conditions.

These processes emphasize the connection between past and present, incorporating a multi-voiced narrative that spans generations. In this model, apologies often come later in the process, after thorough discussions of ongoing inequalities and structural barriers.

Future-focused processes aim to promote long-term societal transformation by addressing the continuing legacy of past injustices and working collaboratively toward systemic change. Rather than placing primary emphasis on apologies, these efforts prioritize joint initiatives, policy development, and shared visions for an inclusive future. This model extends ownership of the process beyond the directly affected community and government to the wider public, recognizing that social justice requires broad-based commitment.

It is important to note that these three models are not mutually exclusive. In practice, many truth and reconciliation processes combine elements of all three. The boundaries between them are fluid, and there is room for innovation and new approaches that do not fit neatly into any single model.

The key takeaway is that there is no one-sizefits- all formula. Each process must be carefully tailored to its unique context, with clear goals and a thoughtful balance between addressing the past, confronting present realities, and building a shared future. For Finland’s process with the deaf and sign language community, this means identifying the most meaningful and transformative approach—one that acknowledges past harm, addresses current challenges, and paves the way for a more just and inclusive society.

A truth and reconciliation process is an official and weighty undertaking—one that typically occurs only once for each marginalized community within a country. Because of its unique and farreaching nature, careful consideration must be given to every aspect of the process: the name, the terminology used, the definition and boundaries of the community involved, the scope of investigation, and the selection of participants and stakeholders, among others.

Transparency and accountability are essential. These principles are not only critical for building trust between the parties involved, but also for achieving the broader societal impact that such a process aims to generate. For the process to lead to real change, it must be seen as legitimate, inclusive, and just—not only by the community directly affected but also by the wider public.

If Finland and the deaf and sign language community succeed in building a meaningful and transformative truth and reconciliation process, it could serve as an inspiring example for other countries around the world. It would demonstrate that reconciliation with disability communities is both necessary and possible, and that historical injustices can be addressed with dignity, collaboration, and care.

As this process unfolds, we will be watching its development with great interest. It holds the potential to reshape how societies reckon with past harms and envision a more inclusive and equitable future.

Reference

Katsui, H., Koivisto, M. K., Rautiainen, P., Meriläinen, N., Tepora-Niemi, S-M., Tarvainen, M., Rainò, P. & Hiilamo, H. (2024) Deaf People, Injustice and Reconciliation: Signed Memories. Routledge. London.