Cinema

David González, Historian, project manager at the EUROM

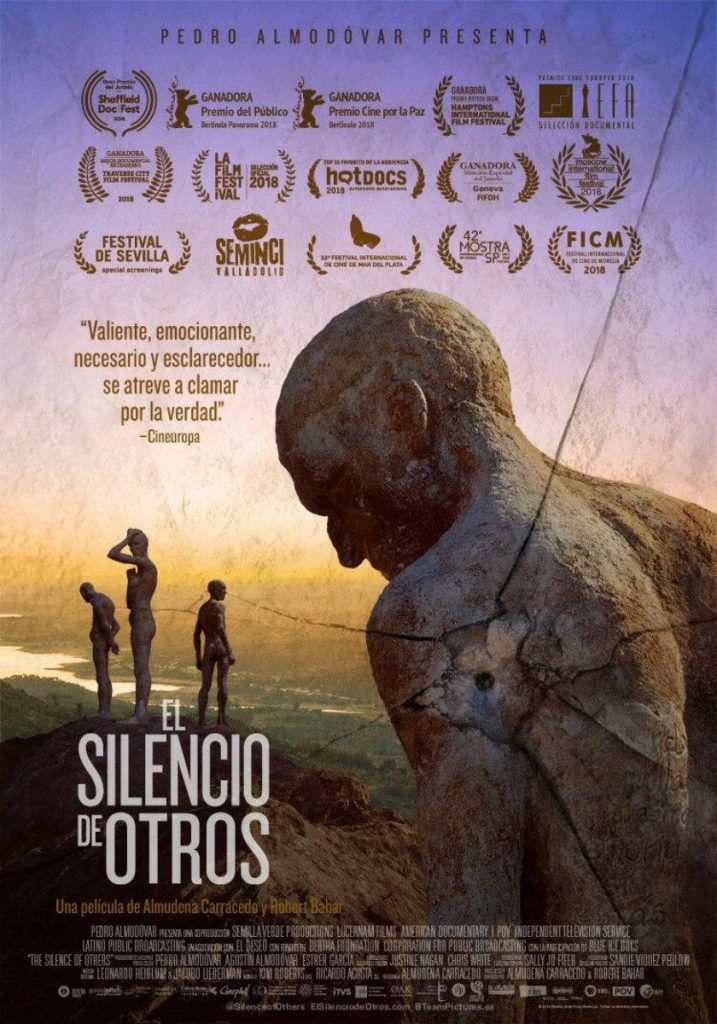

Cover picture: El silencio de otros (2018). Directed by Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar. Produced by El Deseo. 95’ | ©El Deseo

The documentary The Silence of Others (2018) describes the personal and collective struggle in Spanish society to denounce and prosecute the crimes of the Franco dictatorship. Directed by Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar, and produced by, among others, the Almodóvar brothers, El Silencio de Otro has been presented at numerous international film festivals and has won several prizes, among them the Spanish Academy’s Goya award for best documentary in 2019.

The film tells the story of the querella argentina, a lawsuit brought in the courts of Argentina against the crimes of the Franco regime. The film overlays the two processes: the recording and structuring of the documentary, and the legal process itself. In both cases, the protagonists give real-life testimony of the events. The suit was presented in an Argentine criminal court in April 2010, by Judge María Servini, based on the principles of universal justice and the imprescriptible nature of crimes against humanity. In Spain, Judge Baltasar Garzón had earlier opened an inquiry into the crimes of the dictatorship, but was forced to abandon the investigation after being denounced by several ultra-right organizations for breach of trust. Although he was later acquitted, his removal signalled the end of the case in Spain and the termination of any attempt by the Spanish courts to judge the crimes of the Franco dictatorship. So the decision was taken to appeal to international justice: initially, the querella argentina had only two plaintiffs, but they were soon joined by several hundred more thanks to the social mobilization and media campaigns launched in Spain. This mobilization led to the creation in 2013 of CEAQUA, a nationwide group coordinating support for the querella argentina.

El Silencio de Otros shows the complexities of an even broader process in which both the film and thelawsuitare inscribed: the process known in Spain as the recovery of historical memory. The starting point of this process was the first scientific exhumation of a mass grave from the Franco period, carried out in 2000 in Priaranza del Bierzo in León. Over the years, the historical memory movement gradually acquired the scope and the size necessary for the pursuit of its objective: to seek out the truth and to bring justice and redress for the victims of Francoism.

This background is important in order to understand why a trial became the subject of a documentary. The first archive images that appear at the beginning of the film evoke the events that make up the “historical memory” in Spain and highlight the existence of a pacto de olvido (literally, a “pact of forgetting”) of everything that happened before the legislation passed in 1977. Popularly known as the Amnesty Act, it was well received by the political prisoners of the dictatorship, although it also provided protection for the people responsible for state crimes under Francoism. This became known as the Spanish model of impunity: the documentary shows the Basque politician Xabier Arzalluz using this term in the Spanish parliament to describe the legislation.

Although the story is told by several people, the film’s real protagonists are all of Franco’s victims: relatives of people murdered by the regime, who are now fighting to give them a proper burial; the women whose babies were stolen at birth; and the people who were tortured at police headquarters. It was the victims’ families who planted the seed of the movement for reparation, in which the symbolism of a dignified burial would bring the peace that many relatives sought through this process. María Martín and Ascensión Mendieta, two old women, represent the tireless struggle of all those who work to honour the memory of their relatives killed by Franco. María has fought all her life for the right to move her mother’s remains from a roadside ditch to the town cemetery, a dream that sadly she had not seen fulfilled by the time of her death in 2014. She gives chilling testimony of the response of the local Francoist authorities to her request to be allowed to bury her mother in the cemetery: “you’ll take her to the cemetery when the frogs grow hair so stop bothering us – you don’t want us to do to you what we did to her”. Ascensión, who died in September 2019, was able to give her father Timoteo a decent burial in 2017.

The number of babies stolen by the dictatorship is estimated at about 30,000. Justified in the early years of the regime on pseudo-scientific grounds, newborns of women considered unfit to raise them were given to families with links to the regime, a practice that persisted until well into the post-dictatorship period. María Mercedes Bueno gave birth to her baby on 24 December, 1981 at the Municipal Hospital of La Linea, province of Cádiz. Sedated and unconscious during the delivery, she was told upon waking that the baby had died and that the hospital would take care of everything. Twenty-eight years later, reading about several cases of stolen babies in the press, it dawned on her that her baby might be among them. The practice of stealing the babies of left-wing mothers had been instigated at the beginning of the dictatorship by Doctor Vallejo Nájera, a follower of Nazi eugenic theory, intent on eliminating an alleged “red gene” from Spanish society. Over the decades, the stealing of babies became an issue of “morals” more than an ideological one. It lasted well into the 1980s, a symptom of a corrupt plot whose eradication would have required a high-level purge – something that never happened during the transition.

The people tortured by the regime’s security forces have been able to provide firsthand accounts of their experiences. Some of their tormentors are still alive, and the testimony of the victims means that the names of torturers such as Jesús Muñecas Aguilar and Antonio González Pacheco, alias “Billy the kid“, have come to light. Among the torture victims who feature in the documentary is José María “Chato” Galante, whose narrative brings home the reality of state violence and abuse of power so typical of the Franco dictatorship. Galante is also one of the main instigators of the lawsuit.

Whatever the verdicts passed on the defendants in the lawsuit, The silence of others draws attention, on a social level, to an impunity that is still enjoyed by many people close to the Franco regime. Memory, so often projected in a kaleidoscopic way, serves in this film as a bearer of justice. Its infinite nuances are manifested in several moments: for example, the discussion between Luis and Mª Ángeles, the children of María Martín, about the point of delving into the past, or the interaction between the campaigns in Spain and Argentina for the recovery of stolen babies, highlight the complexity of the processes of historical memory and their importance as an instrument for redress. The story of the film is accompanied by impressive photography, as well as several archive images that complement the narrative. Particularly powerful are the images in the trailer, where we see María Martín sitting at the foot of a ditch where the bodies of the unknown victims were deposited, or the panoramic view of the Mirador de la Memoria in the town of El Torno in Cáceres. In this beautiful enclave in the Jerte Valley, since 2008 a sculptural ensemble has paid homage to the victims of Francoism. The monument was made by Francisco Cedenilla, an artist whose grandfather was shot in October 1936.

The silence of others is, in the strict sense of the word, an extraordinary documentary. The quality of the production, the participation of many historical memory associations, and the single-minded dedication of a process that matured over the six years of recording mark the film as a unique achievement. Perhaps most significantly, it is able to reach new audiences which had never seen a depiction of historical memory in Spain. Its airing on state public television in prime time and the high audience figures bear witness to the interest it aroused.

In the face of this media impact, it is not surprising that some critical voices have been raised. It has been said that certain specific data are not presented accurately in the documentary, that the cases of the different victims are not sufficiently differentiated, or that the narrative is excessively fictionalized. Perhaps the term “documentary” is not the most appropriate to name a film whose protagonists, despite being real people experiencing real situations, appear in a story where it seems that the temporary persona prevails over the person. Obviously, The silence of others is a subjective reading of the events. Perhaps the important thing here is to distinguish between a possible caricaturization and a legitimate use of fiction in the interests of creating a more attractive audiovisual language able to achieve the desired aim: that is, to give a voice to Franco’s victims in the laborious and sometimes thankless task of fighting for truth, justice and reparation in a country whose transition to democracy was not accompanied by a clear break with the dictatorial regime that preceded it. Perhaps it is a case of the classic dichotomy between the scientific and the non-specialist, and in this situation the only assessment available to us is a subjective one in which each individual can decide what is more important – whether to be radically faithful to the truth or, whether, without distorting it, to customize it in order to increase its impact. Undoubtedly, there will always be detractors of one or the other option.

The fact that the film prioritizes the sentimental over the documentary is corroborated by the directors themselves. In the many interviews granted by Almudena Carracedo and Robert Bahar, they talk of their main objective: to place the focus on the human element, on small personal stories rather than on large-scale quantitative data. This vision is potentially accurate as long as it manages to reach the public, arousing a personal empathy that transcends abstract discourses and, thus, perhaps, penetrates the collective account.

Can an individual reaction of empathy and solidarity with the victims of the documentary arouse interest in a specific social movement such as the campaign for historical memory? Is the “sentimental” vision the directors bestow on the documentary justifiable? The answers to these questions depend on how we respond to their strategy. We return once more to the field of subjectivity. In my humble and subjective opinion, it is impossible not to empathize with María Martín and her reflections on human injustice, just as it is impossible not to be moved by the sincerity of Ascensión Mendieta. The connection that we feel with these old women in their struggle should encourage us to watch the film without wondering about other issues of a more technical or narrative nature. Through the perseverance and dignity of María Martín and Ascensión Mendieta, the historical memory movement can only be reinforced. And this is memory in its purest form – not data, not clinically exact accounts, but the transmission of a past history for which closure will only be found when amends are effectively made. And as part of a collective process, the attainment of this goal inevitably enhances the value of memory as a means for ensuring that justice is done. All this, always, from the present and into the future.