By Yayo Aznar, National University of Distance Education (UNED)

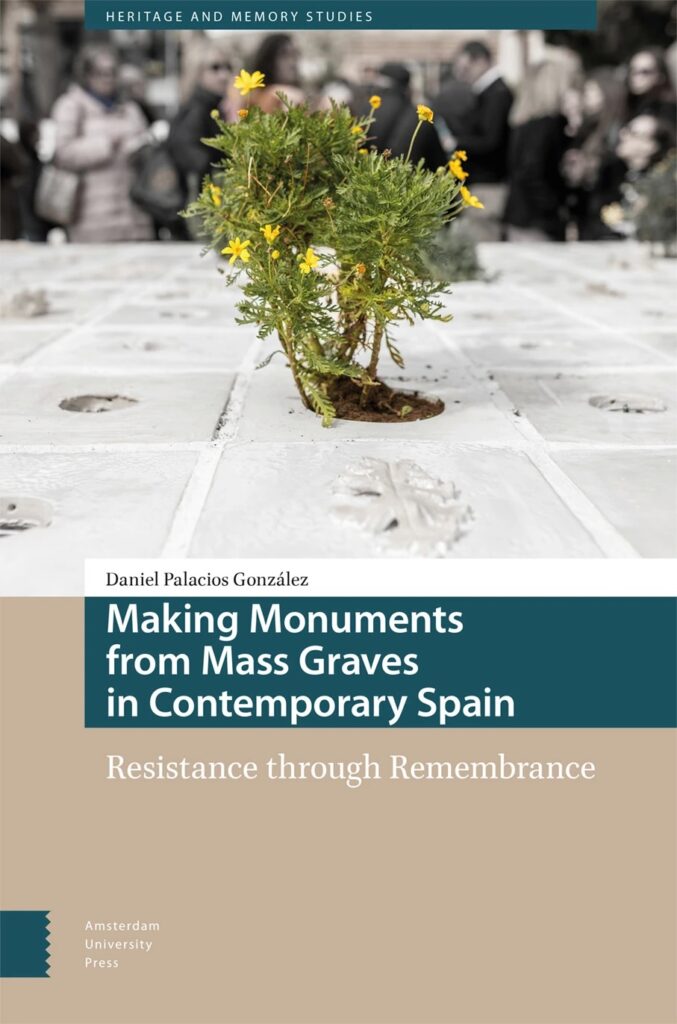

Book: Making Monuments from Mass Graves in Contemporary Spain. Resistance through Remembrance. Daniel Palacios González, 2024 (AHM). International First Book Award of the Memory Studies Association (MSA) in 2023.

We never quite know what to do with memorials. Sometimes we debate whether to tear them down or not, or even consider turning them into outdated memory centres which have proven useless time and time again, beyond allowing the government of the day to draw a line under the matter. Other times, we debate – laden with guilt – whether to build them at all, even launching open competitions for artist proposals, which we usually close with no real conclusion, again to move on from the issue without causing too much pain. Art always has something to say about these matters. In any case, it is clear that all the politics surrounding memorials is a sanctified form of exaltation carried out by current leaders or community figures, as part of a narrative that is useful for power structures or their immediate political interests (Álvarez Junco). So, any debate in this context may seem entirely pointless.

But the fact is, Nietzsche was right: monuments must be of use to humankind, though perhaps not only in the way he explained, and which the 20th-century dictators understood so well. Daniel Palacios’ book focuses on “other memorials” that we do not debate, at least not officially, but that enter the academic world with full merit thanks to this book. These are memorials built through civic initiative, though not always entirely separate from political groups, ones that are created because those involved feel the urge, “as their bodies demand it”. From the first visits by families of those executed to the mass graves during Francoism, to the more “ambitious” memorials after the Transition, the author highlights the creation of small, humble, everyday constructions, often with no aesthetic pretensions whatsoever.

The author believes that memory resides more in the actions of the living than in the bodies of the victims, though that memory would not exist without the presence of the murdered bodies. We must, with Daniel Palacios, understand the monumental practices around mass graves as a gesture, rather than simply an artefact. A gesture that does not end in itself, but in the relationship established between the dead and the living, who read the history in the graves and monumentalism it as a form of experience and resistance, rather than as an institutional decision that can always be debated. In fact, these memorials, which not only include a small stone construction, but also an entire ritual that typically begins when the grave is opened, hark back to the pre-memorials during Francoism (those forbidden visits to the graves, all the strategies to be able to leave even a simple flower at the mass grave, which the book also covers).

By involving bodies in this way, they avoid the risk of becoming monuments to oblivion, because in the bodies of the living, an experience is created. This is similar to what Michelet described after the French Revolution, when he gathered testimonies of people recounting how they saw their region, their fields, their country “for the first time”, no longer deformed by the theological-political institution of royalty, no longer someone else’s property. In other words, an experience tied to the skin and to memory, also tied to our beliefs. The experience is imprinted on the bodies, of both the living and the dead, and that is where memory resides, indisputably, beyond and far above the political management of the moment. Perhaps that is why, because this experience is possible, some families question the emptying of mass graves, and consequently the disappearance of the graves themselves, along with the possibility of a memory filled with fighters, not just victims, filled ultimately with resistance.