MEMORIAL PARK

By Luis Gasca, Undergraduate Student, Institute for the Study of Human Rights, Columbia University Fellowship student at EUROM (2020)

Despite the closures of memorial sites during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 was characterized by its active historical discourse with the spread of the Black Lives Matter protests worldwide. Rather than depend on novel exhibitions for memorialization initiatives, anti-racist activists arduously reflected on controversial monuments of the past. Across the country, centennial monuments honoring slavery and oppression have been defaced and toppled. These events are now immortalized on social media for the removal of traumatic and divisive landmarks across the country.

The controversies surrounding the toppling of monuments on media platforms can only captivate the public for so long. The temporary nature of media attention thus warrants an enduring discussion of what remains of these monuments and also what other existing monuments deserve more visibility. Los Angeles, located in a region founded on the exploitation of Native Californians by Spanish missionaries and a destination for the Black community during the Second Great Migration, is home to two memorials depicting this great disparity in visibility and historical dialogue — the controversial defaced statue of Spanish missionary Junipero Serra and the memorial park of formerly enslaved and philanthropist Biddy Mason.

According to the Los Angeles Times, the outrage behind the toppling of Father Serra’s monument in the city’s historic district began with the indignation of Native Californians over the Vatican’s decision to elevate Serra to sainthood status in 2015. The momentum of the Black Lives Matter protests against Confederate monuments empowered these activists to generate greater historical accountability for Serra’s exploitation of their ancestors.

Visiting Father Serra Park after seeing images of the toppled statue, I was disappointed to find the defaced statue completely removed and the area cleaned up of any evidence. The remaining pedestal, where Serra once proudly held a model mission and cross in his hands, showed no visible signs of protest or alteration. Instead the fenced enclosure and the pedestal’s prominent location continues as a gateway to the historic district of Downtown. It survives with an intact commemorative plaque recognizing Serra’s service to the Church, while being dismissive of the exploitation his mission perpetuated. As it stands today, juxtaposed against the skyline and beautiful landscaped lawns, the monument’s original bias is preserved by far more than its fenced enclosure.

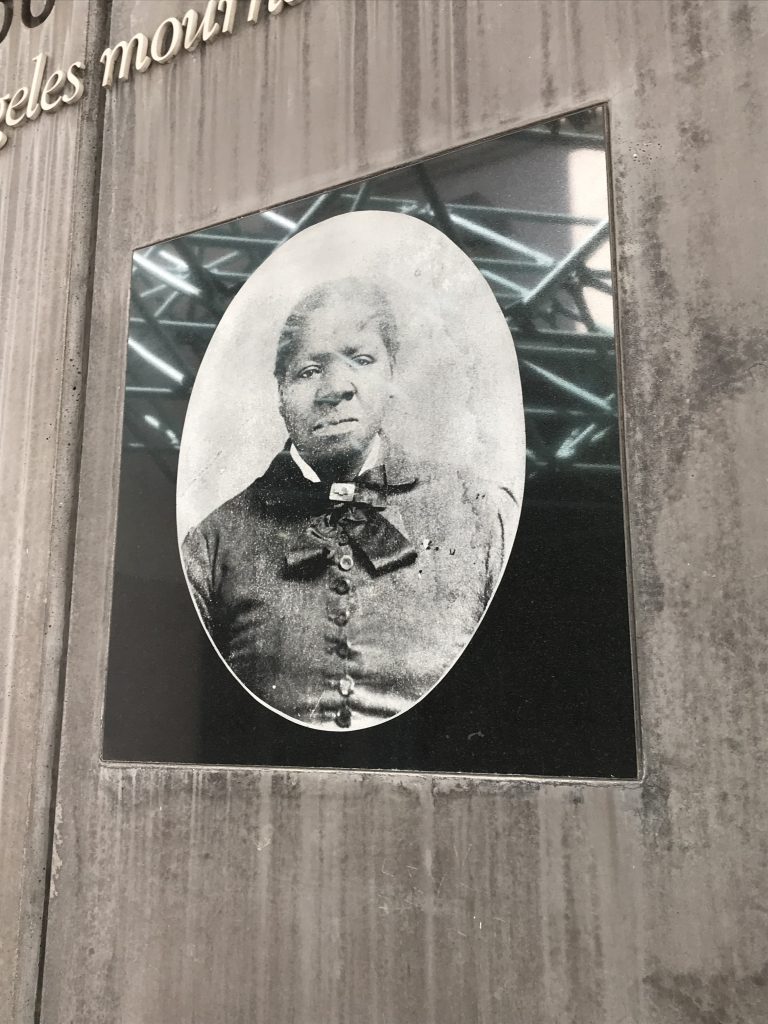

Five minutes away in the heart of Downtown, lies a seemingly inconsequential, 24-meter long, poured concrete wall. Etched with faded portraits, inscriptions, and external molds of miscellaneous biographical

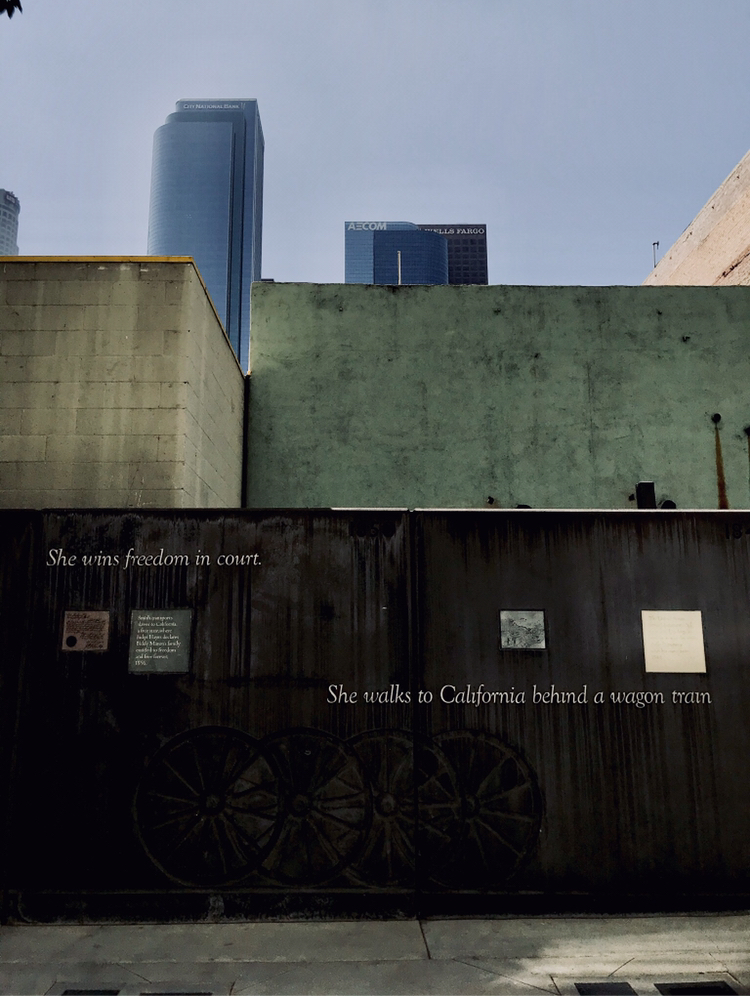

objects, the wall carries a timeline of Biddy Mason’s life as an enslaved person in Mississippi to her life as a successful real estate entrepreneur in Los Angeles towards the end of the 19th century. Regardless of her contributions, the wall’s beautiful simplicity is overshadowed by its placement in a narrow corridor between commercial buildings and a parking structure — a stark contrast to the prominent vantage point Serra still holds even after his statue was publicly defaced and reviled.

Though the wall is placed in a geographically relevant location on the original site of the Mason homestead, the surrounding area holds few visible signs leading to the memorial as opposed to the ones leading to Father Serra Park and other colonial monuments. Lessened accessibility is what makes the difference between visiting one of the memorials on a school trip, stopping by on your commute, or being included in a tour itinerary of Downtown. The surrounding area, thus, gives visitors the first impression of who the historical figures were and how relevant they continue to be. Walking towards the grandiose Serra mount versus the unforgiving shadow and smog from the neighboring parking structure above Mason’s portrait, visitors get a clear indication of what historical narrative receives heightened institutional support.

Inspecting the segments of the wall, I discovered the gradual transformation of the city through much of the 19th century within the context of Mason’s life starting from 1810 on the north side. The timeline begins with demographic information about the history of Mexicans and Americans of African descent within the city rather than with Mason’s own birth. Mason first appears 26 years into her own timeline with the following plaque.

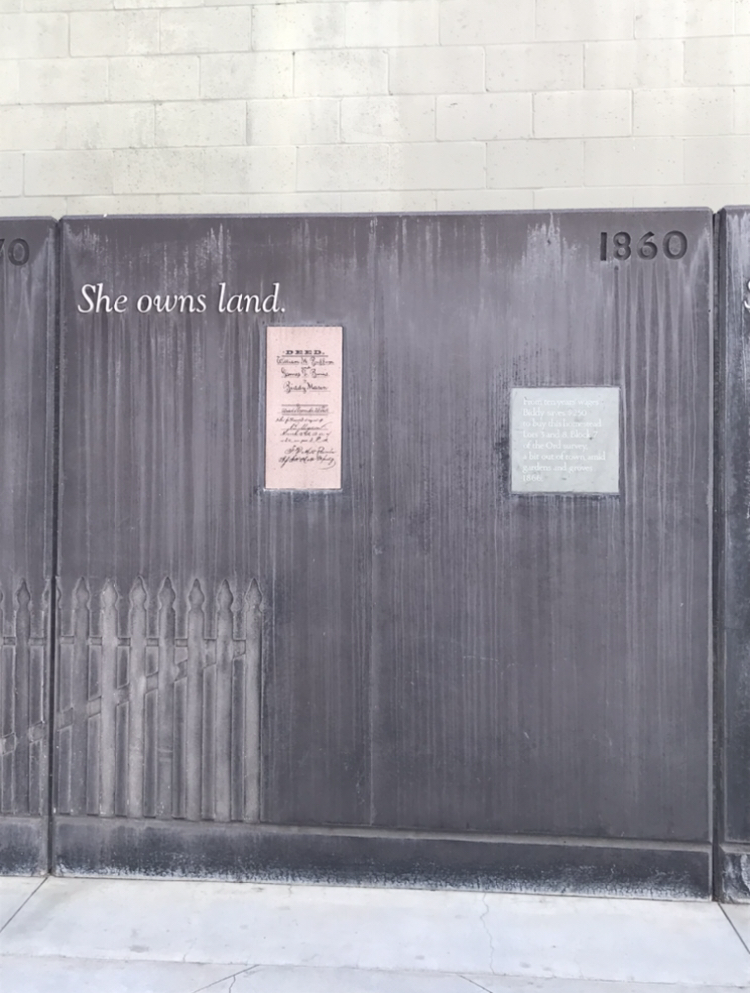

Engraved on a gold plaque, Mason is placed in the greater context of slavery as an 18 year-old who became the property of the plantation-owning Smith family from Mississippi that year. This plaque is found under “She learns midwifery” and next to the external molds of medical instruments used by midwives. This panel of the timeline serves as a powerful transition from Mason’s early life as property to an independent and influential figure in her new community. After 10 years of wages she is able to buy the former homestead I found myself standing in, with a copy of the property deed engraved to the side. The plaques become their most legible and defined when we get closer to her legacy in the city: her grandsons’ commercial ventures, her activism, her philanthropy towards Angelenos made homeless by seasonal floods, and finally for her role in organizing the First African Methodist Episcopal (F.A.M.E.) Church in 1872. The end of the memorial on the south side ends in 1900 before it opens up to the rest of the park leading to the main streets of the 21st century.

Serra’s legacy lives through the trauma of Native survivors while Mason’s activism and entrepreneurship continue to contribute to the welfare of thousands of Angelenos through F.A.M.E. Church. Serra’s memory as a founder seems institutionalized, protected, immortalized through authority and tradition. Mason’s memorial, on the other hand, due to its unconventional placement seems to be preserved by the resistance of a community living with the legacy of her contributions. Installed in 1989, almost a century after her death, the memorial reclaims a sliver of lost land in the middle of the historic site.

As access to new museum exhibitions normalizes towards the end of the pandemic, it is our responsibility to remember the unprecedented historical dialogue that took place in 2020. Historical dialogue fueled by grass-roots organizations confronting institutions and uprooting systems and icons entrenched by landmarks over many generations. We have the responsibility to engage with existing memorials from the perspectives and grievances of today, educating ourselves on the societal forces that tear us down and also those that have built us up.

References

Black Lives Matter protests: Why are statues so powerful?

Perseverance and Place: A Review of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Edward Colston statue replaced by sculpture of Black Lives Matter protester Jen Reid

Activists target removal of statues including Columbus and King Leopold II