Montse Morcate , PhD, artist, researcher and lecturer of photography at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Barcelona

Cover picture: Christian Boltanski. Réserve des Suisses Morts, 1991

The contemporary photographic art project has incontrovertible value as a tool for transmitting and reflecting on historical memory and genocide. In this respect, teaching in the field of arts and art practices can create contexts for discussing and reflecting on a diverse range of aspects from various perspectives. These include the mechanisms that allow the complexity of individual, collective and historical memory to be transmitted, as well as the role of image as a mediator, as both a work of artistic expression and the document of a historical event. With this in mind, the paper aims to provide a brief overview of different art projects that not only review and reflect on the historical event they portray or allude to, but also question the role of documentary photography as a hegemonic resource for bearing witness to, recovering or reconstructing historical memory itself. Moreover, the paper examines other aspects of image as a medium that challenge the capacity of photojournalism to generate a reaction and raise awareness of tragic events in the present. In this respect, photographic art projects offer an infinite spectrum of visual content in which the image used is created, appropriated or transformed within its numerous contexts, including family or home photography, staging or simply the evocation of the image itself. The objective of these practices is not simply to be creative and experiment with the visual; rather, they aim to offer cross-disciplinary perspectives that make extremely complex and sensitive issues approachable in such a way that they expand and question the limitations of photography within the framework of documentary, photojournalistic or archival practice.

Many contemporary artists have directly addressed or alluded to the Holocaust, the diaspora and the survival of the Jews. Key examples include the work of Christian Boltanski and his archival perspective with installations such as La Réserve des Suisses morts (1990) (The Reserve of Dead Swiss), in which photographs appropriated from obituaries in a Swiss newspaper are enlarged until the faces shown are obscured, altering their context and meaning, thereby managing to evoke the Holocaust without referring to it directly. As Van Alphen states, there is a clear Holocaust effect in the work, as evidenced in “the sheer number of similar portraits, which transforms the sense of individuality typically evoked by that genre into one of anonymity”. Indeed, he continues, “the work can thus be seen as a re-enactment of one of the defining principles of the Holocaust: the transformation of subjects into objects”. (Van Alphen, 1997, p. 106).

Other particularly relevant examples include the works of Art Spiegelman and his graphic novel Maus (1991), which recounts the experiences of his father, a Holocaust survivor, as well as his own story as a son; David Levinthal’s Mein Kampf (1993–1994), which recreates scenes from the atrocity using toy figures; and Shimon Attie’s project The Writing on the Wall (1991–1992) in which the artist retrieves archive images of the everyday lives of the residents of Berlin’s Jewish quarter and projects them onto their location sixty years later, superimposing them in both time and space. Moreover, all these works share the same distance in time from the events and, as such, the artists do not portray their own experiences in their work, but rather approach the subject indirectly. As James E. Young explains, for these artists, “their subject is not the Holocaust so much as how they came to know it and how it has shaped their inner lives”. (Young, 2000, p. 3). It follows, then, that the work of these artists was inspired by a range of direct and indirect sources, including media publications and images, testimonies, documents, and family accounts, and that it deals not only with the Holocaust but, more specifically, with the transmission of historical memory. Many artists’ work also addresses their own identity as descendants of survivors, and the responsibility to keep their memory and history alive. In this sense, the main theme of many of these projects is ‘postmemory’(Hirsch, 1997), referring to memory transmitted by the preceding generation that has had such an importance, presence and influence in a person’s life that they embrace the memory as their own.

Rafael Goldchain’s photographic project I Am My Family (2008) is an excellent example of an art project that brings together issues of family, identity and history in a deceptively simple way.

I Am My Family features a series of portraits in which Goldchain transforms himself into his own relatives through the elaborate use of makeup and clothing to recreate old photographs from the family archive. While it may first appear to be a simple and playful exercise in emulating and recreating the traditional family album, there are other far more complex interpretations hidden underneath the surface. Firstly, the artist experiments with recreating his direct family members and ancestors through the medium of the portrait, blurring the limits of the concept of self-portrait and, as a result, the brutal connection established with family identity in this way and the genetic inheritance that they have passed down to the artist himself. In this respect, it makes perfect sense for Goldchain to try and explain his origins and family lineage through his own person, challenging the observer to imagine the likely similarities and differences between the relatives represented, just as we do when browsing through traditional photograph albums.

However, I Am My Family also goes far beyond depicting an average family. Each portrait is accompanied by the relative’s name and their date and place of birth and death. It is this aspect that takes the family portrait to a new level, representing the origin of a Polish Jewish family, the terrible fate many of them suffered and the subsequent diaspora of the survivors, who would end their lives in places as far-flung from one another as Argentina, Chile and Israel, their surname undergoing various transformations, but they themselves never losing sight of their common origin. And at the same time this sensational project tackles a topic as huge as the Holocaust in an apparently playful way, using the family album and its representation as a vehicle for observers to connect with the subjects in the portraits in the same way as they do with their own family images. Meanwhile, the photographs serve as a tribute to each relative, portraying them as individualised and irreplaceable people, while also transforming them into just one of the millions of families who suffered a similar fate and whose legacy endures today through their descendants. Moreover, the work directly portrays survival against all odds, symbolised through the artist’s face and the play on words in the title of the project.

© Alfredo Jaar, courtesy of Thord Thordeman, Malmö, and Galerie Lelong, New York.

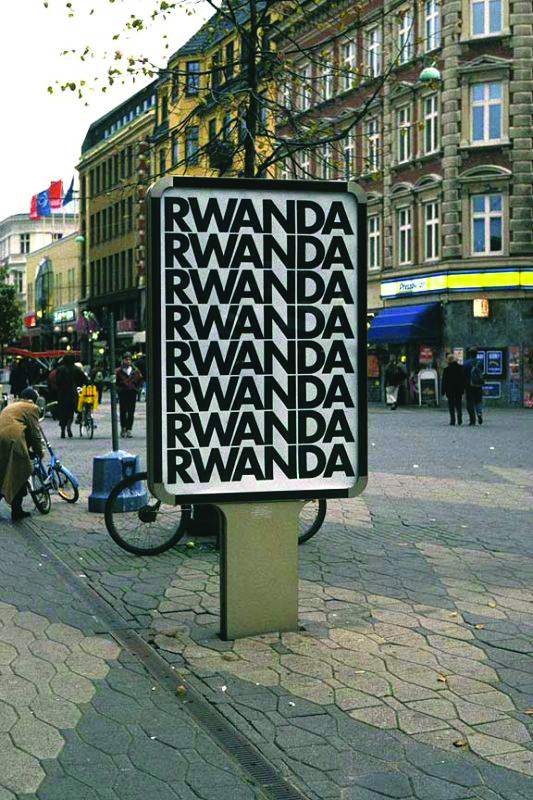

As a counterpoint to the above mentioned works, it is worth highlighting, albeit briefly, The Rwanda Project (1994–2000) by the artist Alfredo Jaar, about the genocide in the country. In contrast to the other artworks, Jaar’s work presents the genocide as a fact produced in the present, as is its representation. This large-scale project comprising more than twenty artworks is remarkable for offering different standpoints on what happened during the Rwandan genocide, while also questioning the capacity of photojournalism and its distribution and exhibition mechanisms as an effective tool for mobilising the population in the face of an atrocity of this magnitude. In this respect, not only does Jaar expose the weaknesses of the medium but, through his artworks, he proposes other potential strategies for generating visibility, reflection, reaction and emotional response through art. He manages to represent the genocide and its aftermath without directly showing the literal nature of the brutality, violence or death, without exploiting the victims, yet reflecting the complexity of an event of this scale. As the artist himself states, “If the media and their images fill us with an illusion of presence, which later leaves us with a sense of absence, why not try the opposite? […] People were already shown a great quantity of images, but they did not see anything. No one saw anything because no one did anything. Then I thought, this time I won’t show the images so that people can ‘see’ them better.” (Jaar, Gallo, 1997, p. 59). This approach is particularly clear in of the project’s installations, Real Pictures (1995), in which a number of black filing cabinets containing images of the genocide are placed around the exhibition space. The observer can see the description of the images on the outside of the cabinets but the photographs are kept hidden. One of the descriptions reads:

Benjamin looks directly into the camera, as if recording what the camera saw. He asked to be photographed amongst the dead. He wanted to prove to his friends in Kampala, Uganda that the atrocities were real and that he had seen the aftermath.

In this way, the installation becomes a space that evokes what is invisible to the eyes, while the very structure envelops the observer in a kind of memorial. “The theatrical staging here with its resplendent light functions both as a memorial to the victims of the Rwandan genocide as well as a conduit or means to persuade and sustain consideration of this brutal event.” (Bricker, 1999, p. 25)

Another large-scale installation that forms part of Rwanda is The Eyes of Gutete Emerita (1996), consisting of a long passage of text introducing the observer to the context of the genocide, before continuing with the following testimony:

On Sunday morning at a church in Ntarama, 400 Tutsi men, women and children were slaughtered by a Hutu death squad. Gutete Emerita, 30 years old, was attending mass with her family when the massacre began. Killed with machetes in front of her eyes were her husband Tito Kahinamura, 40, and her two sons, Muhoza, 10, and Matirigari, 7. Somehow, Gutete managed to escape with her daughter Marie-Louise Unumararunga, 12. They hid in a nearby swamp for three weeks, coming out only at night in search of food. Gutete has returned to the church in the woods because she has nowhere else to go. When she speaks about her lost family, she gestures to corpses on the ground, rotting in the African sun. I remember her eyes. The eyes of Gutete Emerita.

In an adjacent space, a large heap of thousands and thousands of slides all contain the same image: a close-up of Gutete Emerita’s staring eyes. The work is moving not only because of its physicality, which alludes to the million victims of the genocide but also because it evokes all the survivors of the tragedy, giving value to their history rather than merely representing it (limited here to recording her stare but preserving her anonymity). At the same, the observer connects with the image in a brutal way.

The above works are just a few examples of projects that, through art, manage to ask questions about such issues as the transmission of history and the testimony of its survivors. At the same time, their photographic discourse proposes alternative forms of representation that break away from the traditional conventions associated with memory, history and documents.

References

Bricker Balken, D (1999) Alfredo Jaar: Lament of the Images. List Visual Art Center, MIT: Boston.

Jaar, A. & Gallo, Ruben (1997) “The limits of representation” in Trans vol. 1/2, Issue 3/4.

Hirsch, M (1997) Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory, Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Van Alphen, E. (1997) Caught by History. Holocaust Effects in Contemporary Art, Literature, and Theory. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Young, J. E. (2000) At Memory’s Edge: After Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.