Reed Brody. Human rights lawyer and author of To Catch a Dictator: The Pursuit and Trial of Hissène Habré.

He has worked alongside the victims of the former dictator of Chad, Hissène Habré –who was convicted of crimes against humanity in Senegal– and in the cases of Augusto Pinochet and Jean- Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, and currently works with victims of Gambia’s Yahya Jammeh and of Saudi Arabia’s Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Cover image: The “Piscine” was a colonial-era swimming pool, which Habré converted into a secret underground prison. Photo by Reed Brody

As we descended the staircase into the most notorious underground prison of Chad’s former dictator Hissène Habré, I could tell from the pervasive cobwebs that no one had been down there in years. The “Piscine” had once been a colonial swimming pool, reserved for the families of French soldiers. Habré perversely had the pool covered with a concrete roof and divided it into ten cells where the “DDS”, his political police, crammed together hundreds of desperate prisoners of the Zaghawa ethnic group, men like Ismael Hachim, who was now leading me down the stairs.

Habré had taken power in Chad in 1982 with American support as bulwark against Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, and was finally overthrown in 1990 and fled across the continent to Senegal. Hachim had survived the Piscine and was now the president of the victims’ association, and I was representing the victims on behalf of Human Rights Watch. In 2000, inspired by the London arrest of the former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, on whose case I had also worked, we filed a criminal case against Habré in Senegal. And now in 2001, we were looking to build that case and discover the truth about Habré’s crimes.

In a few cells, tally marks on the walls recorded the prisoners’ days in detention. In other places, detainees had written heartbreaking messages in Arabic or French, Chad’s two national languages. “Man is made for death and suffering”, one of the etchings said. The cells were twelve feet high, with a small opening at the top for air and light. In theory, the macabre Piscine dungeon was now off limits because it was part of an army base adjoining the presidential compound of Idriss Déby, who had overthrown Habré. But Hachim used his connections to Déby, a Zaghawa like him, to get me in, along with my colleague Olivier Bercault, Pierre Hazan, a Swiss journalist making a documentary, and Pierre’s cameraman. Officials from Déby’s office accompanied us on the visit. When we climbed back out of the Piscine into the daylight, I took the opportunity to ask them if we could also take a look at the abandoned headquarters of the DDS, whose distinctive circular fronting we could see just on the other side of a wall. Providentially, they agreed.

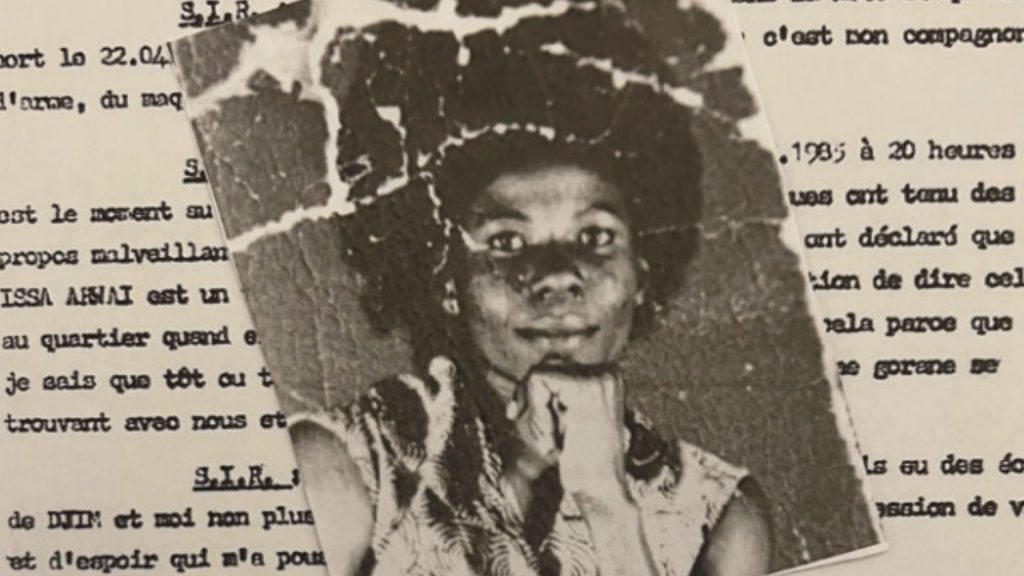

We walked through the dusty rooms of the DDS headquarters until we came to one strewn with documents shin-deep on the floor. Nobody had been here for a long time, and as I bent down, I had to wipe away the cobwebs. The first thing I scooped up was a file on a DDS detainee, the next a report on rebel activity. Olivier and I kept digging. We found lists of DDS prisoners, death certificates, interrogation and spying reports, identity cards. Once we’d waded through the first room, we found two more filled with the same discarded papers. By all appearances, these DDS files had been languishing here, unnoticed, for the past eleven years.

This was, as we recognized immediately, the mother lode. El Dorado. Nothing could be more valuable in the case we were mounting against Habré than the cold, bureaucratic records of his own underlings. Pierre’s camera captured the moments of our discovery on film. Our escort from Déby’s office said–also on camera–that the documents were ours if we wanted them. I could hardly believe what he was saying. But after saying it once, he said it again. In my mind, I had been plotting how to stuff some of the juicier documents into my pockets, but now, apparently, I didn’t have to.

Taking official possession of the documents was still not easy. Nothing in Chad ever was. It took months of negotiations before Hachim and his victims’ association were allowed to come on site and copy–not take–the documents. And it took months more for a team of volunteer victims to go through the offices room by room, sort the documents, and put through them through a manual copier that they brought on site each day. The leader of this recovery team was Sabadet Totodet, a former DDS detainee whose prison tasks included dumping the bodies of fellow inmates in a mass grave on the outskirts of N’Djamena. In an important sense, he was resurrecting the people he had previously been assigned to bury.

Sabadet and his fellow volunteers began work at dawn each day and worked until the heat became unbearable in the early afternoon. Once they had amassed their copies, the victims’ association made another copy and sent it all along to my office at Human Rights Watch in New York.

The picture that the documents painted of the DDS and its inner workings was chilling. But it was also exactly what we’d been looking for. Among prosecutors, documents are known as the king of evidence. The truths they reveal can’t be cross-examined; their memories do not fade.

According to the wording of a 1983 decree establishing its existence, the DDS was directly responsible to Habré in person. Whatever the agency did, Habré knew about it, as we could tell from the hundreds of documents keeping him informed on a daily basis of even the smallest details of its activities. And the DDS was never less than proud of doing Habré’s bidding. «Thanks to the spider’s web [we] have spun over the whole length of the national territory,» the director boasted in one memorandum, «[we] keep exceptional watch over the security of the state.»

Arrest records documented the sorts of infractions that could land a citizen in serious trouble: making insulting remarks about the president, accusing the president of stashing money abroad, sorcery (maraboutage) on behalf of the enemy, possession of a photo of Qaddafi, possession of a letter describing the repression in the south of Chad, even being a member of a Rastafarian club.

Few documents explicitly mentioned torture, but the language did little to disguise what went on. «It was in compelling [the prisoner] to reveal certain truths that he died on October 14 at 8 o’clock», said one report. Another detainee «only admitted certain facts … after physical discipline was inflicted upon him». In many places, the documents talked of “muscular” interrogations.

We found hundreds of death certificates. The causes listed included severe amoebic dysentery, severe dehydration, arterial hypertension, severe edemas of the upper and lower limbs and what was often described as, «general deterioration of health». The vaguer descriptions could sometimes be just as sinister as the more specific ones. One document listed fourteen Zaghawa prisoners, arrested in April 1989, who «died due to illness» later that month. Another named 32 prisoners of war who all died «from their wounds» on the same day.

The bureaucratic language attested clearly to the waves of repression in the south of Chad and ethnic cleansing against groups like the Hadjerai and the Zaghawa. One report from 1989 was titled «Situation of the traitorous Zakawa agents arrested for complicity» and it listed 98 people –shepherds, drivers, students and businessmen– who had been arrested as «suspected accomplices of the traitors».

One of the first documents that Olivier and I found on the floor was a report by twelve Chadian security officials, including several later accused of torture, which described a “very special” training they attended near Washington in March 1985. Another document spoke of a Chadian request to the United States for truth serum and a generator, to be used in “interrogations”. The United States had known about Habré’s atrocities, of course, but to what degree did it actively participate? I would spend years trying to find out and never got as close to the truth as these documents were taking me. My dozens of Freedom of Information Act requests in the US only got back a lot of descriptions of military assistance and embassy meetings, but nothing regarding the training.

Habré’s first and longest-serving DDS Director, Saleh Younous, had told Chad’s Truth Commission in the early 1990s that «a certain John, an American, was acting as my advisor». Bandjim Bandoum, a former sub-director of the DDS, would also later tell me about “John”. The veteran French war correspondent Pierre Darcourt told me he’d heard of an American advisor to the DDS director called “Mr. Swicker”, an account supported by DDS logbooks that recorded visits by “Mr. George Swicken” and “Mr. Swica.” One such visit to DDS headquarters, on April 7, 1989, took place as the repression of the Zaghawas was at its height and the Piscine, only a few yards away (and across the street from the USAID office) was filling up with Zaghawa prisoners.

I checked the State Department’s staff listings and found a George S. Swicker, who served as the political and military counselor at the U.S. Embassy in Chad in the late 1980s. His predecessor was James L. Morris, a possible match for a person described in a DDS document as the «American Advisor to the DDS, Monsieur Maurice».

I never found Morris, but I traced Swicker to an address in Virginia. He never returned my calls.

The documents also talked about a secret U.S.-backed network called “Mosaic”, which linked the security services of the Côte d’Ivoire, Israel, Chad, Togo, the Central African Republic, Zaire and Cameroon. Mosaic’s apparent purpose was to make sure political opponents of one regime could find no haven in any of the other participating countries. One former DDS deputy director who was spilling secrets to Amnesty International, for example, was kidnapped in Togo in 1988, and delivered back to Habré, who threw him in jail where he starved to death. The model was strikingly similar to Operation Condor, the Pinochet-era alliance of Latin American intelligence services whose victims included Orlando Letelier, the former Chilean ambassador to Washington, killed in a car bombing in the U.S. capital in 1976.

The documents also revealed startling cases of heroism, like that of Rose Lokissim, who had been jailed in the mid-1980s for assisting southern rebels. Rose was legendary among survivors of the “Locaux” prison where she spent six months as the only woman with 60 men in Cell C, the “cell of death”, before being transferred back to the regular cells. She helped two detainees deliver babies in custody and was known for her ability to boost people’s morale. Clément Abaifouta, who would become the president of the victims’ association after Ismael Hachim’s death, remembered that in jail Rose would tell people, «Stay strong until we can get out of this prison. Then we’ll change the direction of things in this country. She was a revolutionary, because she had ideas that fired us up to revolt, to dream of a change. At that time, we were all afraid.» When prisoners died or were executed, Rose noted the abuses on scraps of paper and smuggled the information out to relatives. Ultimately, she was denounced by a fellow prisoner and killed.

What nobody knew until we found the documents was how bravely Rose had gone to her death. After she was betrayed, the DDS interrogated her on May 15, 1986 and recorded her telling them: «If I die here, it will be for my country and my family. History will talk of me. I’ll be thanked for my service to the Chadian nation.»

The DDS interrogators concluded that Rose was «irredeemable and continues to undermine state security, even in prison», and recommended that «the authorities punish her severely».

She was executed that same day.

This story haunted me like no other, and I marvelled at the fact that her words, spoken only to her tormentors, had found their way to me after fifteen years, like a note in a bottle washing ashore. Rose wanted history to talk about her, and now I had the material in my hands to make sure it would do just that.

At Human Rights Watch, a team of seven interns spent six months organizing the DDS files into a searchable database. Patrick Ball, the “statistician of the human rights movement”, who had assembled data for truth commissions and courts in Guatemala, Haiti, South Africa and Kosovo, gave us our first analysis of the extent of the Habré regime’s crimes. The documents mentioned 12,321 different victims and 1,208 deaths in detention. Habré received 1,265 direct communications about the status of 898 detainees.

We had a few documents bearing what appeared to be Habré’s handwriting, including one in which he refused a Red Cross request to hospitalize prisoners taken on the battlefield. But what was the most incriminating thing was the sheer number of crimes committed around Habré, their systematic nature, and the fact that so much information about them was being sent to him directly. Here, in black and white, was overwhelming proof that he knew what was going on and, at the very least, did not put a halt to the crimes. We could, in legal parlance, ascribe “command responsibility” to him and use it as a basis for charging and convicting him.

Despite this evidence, and Habré’s first indictment in 2000 by a Senegalese judge, however, the Government of Senegal refused for more than a decade to allow the case to advance. For that, it would take one of the world’s most patient and tenacious campaigns for justice by a group of survivors, a 2012 ruling obtained by Belgium from the International Court of Justice ordering Senegal to prosecute Habré “without further delay”, and the election the same year of a new president, Macky Sall. Under Sall’s leadership, Senegal and the African Union created special chambers within the Senegalese court system, which in July 2013 again indicted Habré and finally paved the way for his trial. It was the first time in history that the courts of one country, Senegal, prosecuted the former leader of another, Chad, for human rights crimes.

The victims’ mobilization also led to a trial in Chad that, on March 25, 2015, convicted 20 Habréera security agents on charges of murder, torture, kidnapping and arbitrary detention. The court sentenced seven men to life in prison, including Saleh Younous, the former director of the DDS, and Mahamat Djibrine, described as one of the “most feared torturers in Chad” by the Truth Commission. In addition to reparations, the court ordered the government to erect a monument to those who were killed under Habré and to turn the former DDS headquarters into a museum. These were both among the long-standing demands of the victims’ associations. Seven years after the court decision, however, the Chadian government has not implemented any of these compensatory measures.

In the run-up to Habré’s trial in Senegal, Spanish filmmaker Isabel Coixet produced the documentary Talking about Rose, narrated by the French actress Juliette Binoche, which told the story of the courageous Rose Lokissim. The film was first shown to a packed audience in Chad during the trial there and introduced Rose’s story to a Chadian public that had not heard of her before.

After the film, the Humanity United Foundation in California created “Rose Lokissim Grants” for reporters to travel to Chad and Senegal and cover the Habré case. Their stories about the trial wound up in the New York Times, The Guardian, and El País, among other publications, bringing Rose’s story and the victims’ struggle to an even larger audience.

Habré’s trial finally began in July 2015 in Dakar, and was streamed on the internet, televised in Chad and uploaded and stored on YouTube.

The DDS documents we had discovered took center stage at the trial, buttressing the testimony of 98 witnesses. A court-appointed handwriting expert confirmed that it was Habré who responded to a request by the International Committee of the Red Cross for the hospitalization of certain prisoners of war by writing «From now on, no prisoner of war can leave the Detention Center except in case of death». The statistician Patrick Ball presented a study of mortality in Habré’s prisons, based on the DDS documents, concluding that prison mortality was «hundreds of times higher than normal mortality for adult men in Chad during the same period» and «substantially higher than some of the twentieth century’s worst POW contexts», such as German prisoners of war in Soviet custody and U.S. prisoners of war in Japanese custody.

Numerous prisoners talked about sharing their cells with Rose Lokissim and the court received all the documents detailing her tragic and brave story.

The most dramatic testimony at trial came from four women sent to a camp in the desert north of Chad in 1988 who testified that they were used as sexual slaves for the army and that soldiers had repeatedly raped the women in the camp. Two were under 15 at the time. The recovered DDS documents confirmed that women were sent to the desert and record the imprisonment of the four former detainees who testified. One of the women, Khadidja Hassan Zidane, stunned the court when she testified that Habré himself had personally raped her four times in the presidential palace. Kaltouma Deffalah, one of the survivors of sexual slavery, testified defiantly that she felt «strong, very courageous because I am before the man who was strong before in Chad, who …doesn’t even speak now, I am really happy to be here today, facing him, to express my pain, I am truly proud». It was a sentiment expressed, in one way or another, by many of the survivors who testified.

One evening during the trial in Dakar, I had a chance to watch on satellite the Chadian television coverage of the trial and was struck by the idea of thousands of Chadians watching their former dictator in the dock. Habré wasn’t in the dock because Chad’s current strongman Idriss Déby had so decreed, which was the way things usually happened in Chad. He was there because a group of brave citizens, Ismael Hachim, Sabadet Totodet, Clément Abaifouta and so many others, had fought furiously for years to get him there, because people like Rose Lokissim had dared to tell the world what happened in Habré’s prisons. The power of their achievement was nothing less than revolutionary.

On May 30, 2016, the court convened before a packed audience to deliver its judgment. It found Habré guilty of the commission of crimes against humanity, for the underlying crimes of rape, sexual slavery, the massive and systematic practice of summary executions, and kidnapping of persons followed by their enforced disappearance) and of torture. It also found him guilty of war crimes, including murder, torture and inhuman treatment, under the principle of command responsibility. The court found Khadidja Hassan Zidane’s testimony that Habré raped her to be credible. The court’s opinion cited the case of Rose Lokissim 15 times.

Noting that torture and repression were Habré’s form of governing, the court sentenced him to life imprisonment.

The conviction and the sentence were upheld on appeal and Habré died on August 24, 2021, while serving his life sentence.

After Habré’s conviction, several of the protagonists of the victims’ campaign created a “Rose Lokissim Association”, funded principally by the charitable foundation of the exiled Mauritanian businessman Mohamed Bouamatou, to carry on the victims’ quest for full reparations and to carry the fight to other tyrants such as Gambia’s Yahya Jammeh.

Rose was 33 years old when she was killed in 1986, but thanks to the discovery of her last words, and the tenacity of the survivors in bringing Habré to court, her memory lives on.

As Juliette Binoche says in the film, «Rose’s chosen mission, for the world to know the truth about Hissène Habré’s prisons, is finally being achieved».

And history is indeed talking about Rose.