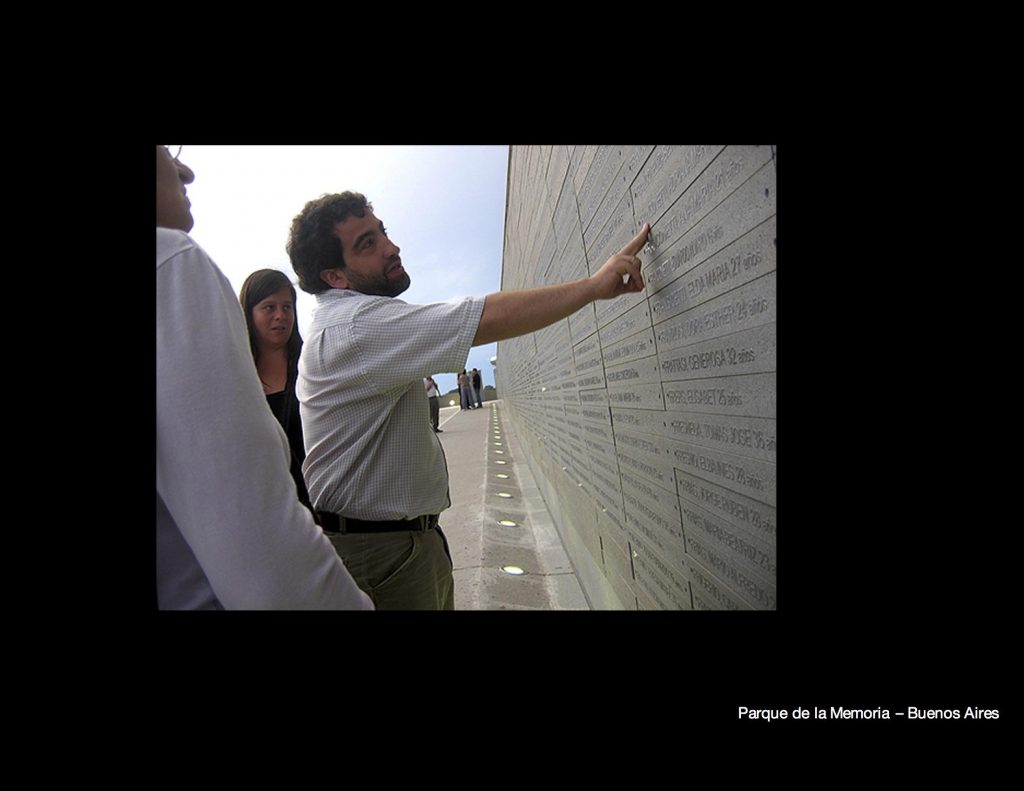

Picture: Parque de la Memoria, Buenos Aires

Julian Bonder , Architect

Julian Bonder + Associates & Wodiczko + Bonder

Professor at Roger Williams University, Bristol, Rhode Island

“The Act of Remembering is of the Present and its reference is in the past and thus absent”

Andreas Huyssen [1]

“Society is the miracle of moving out of oneself”

Emmanuel Lévinas [2]

Few words have been so ubiquitous in contemporary culture as the word “memory”. Since the 1980s the – perhaps obsessive – pursuit of memory has become omnipresent. Memory in its many forms has become a key marker in such diverse fields as historiography, psychoanalysis, visual and performative arts, information technology, and media studies. The culture of memory has impacted the relationships between politics, architectures, public art and public space, as well as the conception, creation and realization of various forms of expression of memory in our cities.

The construction of memorials and museums all over the globe seems significant in the sheer vastness and magnitude of their number, as well as in the significance that these sites of memory may have in, and for, affected communities. Examples of this are the creation of official and community-based memorial spaces, the emergence of spontaneous memorials, pilgrimages to sites of memory, and many other forms of commemorative practices. Even though the ‘culture of memory’ has spread over the globe, and memory’s political uses are varied, at their core, these remain tied to the histories of specific communities, nations and states. An important aspect of the culture of memory may be found in the way the struggle for justice and human rights and the remembrance of traumatic events have been strongly linked to one another, as many nations – Germany, Chile, Spain, Mexico, Rwanda, South Africa, Argentina, Colombia, United States, Guatemala, Peru among so many others – seek to create democratic societies in the wake of histories of mass exterminations, slavery, apartheids, segregation, military dictatorships, and totalitarianism.

Even though monuments and memorials have been built around the globe for many centuries, the atrocities, crimes and disasters of the recent past have been self-consciously inscribed into our build environment as never before in history. Few cities in Europe, South America or the United States do without public spaces dedicated to some such commemoration, and the nearly instinctual response of public authorities and communities, to public debates on such diverse issues as the “desaparecidos”, the Holocaust, recent wars, civil rights and slavery is to erect some kind of physical marker about these complex and difficult histories. Memorials in such diverse locations as Washington D.C. and Berlin, Buenos Aires and Krakow, Gorée and Nantes, Liverpool and Santiago, New York and Barcelona, remind passer-bys of wars, genocides and crimes against humanity. As a result, architects and artists, alongside with activists, public historians and cultural agents find themselves playing an important role in public discourses about history, memory, ethics, politics and the public domain.

So, how do we understand the critical significance of design, art, architecture and action in the public sphere upon conceiving and creating memorial spaces and democratic public spaces? How can we contribute to elaborate the ethical implications of Arendt’s description of the public sphere, and by extension the democratic public space, as “the space of appearance” in the widest sense of the word? How do we position ourselves as architects, artists, teachers, and students, when working on such projects? Architectures, landscapes and public spaces, serve to frame human experience, and at the same time, are catalysts for the process of memory. Historically the architect’s role has been to create a theater for action and of memory, capable of embodying truths that make it possible to affirm life and contemplate a better future. While we, as architects (and artists), imagine projects and embark on journeys that leave traces over the skin of the earth, our work often lies in unveiling, unearthing and uncovering, as well as anchoring histories and memories in and onto territories, sites, and cities. It is in the face of catastrophes, historic traumas, and human injustices that the architect’s (and artist’s) public roles become increasingly complex and problematic but also necessary.

Memorials, Monuments, Public Space

A memorial’s historic role is to preserve a memory of the past and provide conditions for new responses to and in the present. “Memorial”, “memento”, “monument” (like “monitor”) suggest not only commemoration but also to be aware – to mind and remind, warn, advise, and to call for action. As our political and ethical companions, memorials should function as environments for thinking about the past and the present, fostering a new critical consciousness in democratic public space. The Latin word monumentum derives from the verb monere (“to warn”), and thus signifies something that serves to caution, or remind with regard to conduct of future events. Instead of a form, a shape, or an image, monumentality may well be a quality, the quality that some places or objects have to make us recall, evoke, think, and perceive something beyond themselves. As a place of memory work and common remembrance, a monument or memorial is intended to be historically referential. As embodiments of memory through art in the public realm, their value is not only based upon or derived from the artwork but from their ability to direct attention to larger issues, a certain point beyond themselves. As James Young notes in The Texture of Memory: “their material presence is meant to turn invisible, transparent, bridging between the individual memory work and the events or people they recall”. Their significance lies in the public dimension and the “dialogic character of memorial space”, that is, the space between the stories told or the events remembered, and the act of remembrance (memory work) they help frame. To be public and to be in public is to be exposed to alterity. According to Hannah Arendt, political equality means visibility; conversely, political inequality and invisibility go hand in hand. Hence, in considering Arendt’s notion of the public sphere as ‘the space of appearance’, we should question not only of how we appear but of how we respond to the appearance of others – those others that, as French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas reminds us, are not an object of comprehension but an enigma of a Face that resists possession, cannot be fully known and cannot be reduced to content. That is, at its core, a question of the ethics and politics of living together in a heterogeneous space. If democracy, as Claude Lefort reminds us in “The Question of Democracy”, is based on uncertainty and legitimized by the declaration of rights – the right to declare in public, among them – and by the presence of others, we should recalibrate how we assess the success of democracy and indeed of democratic public space. These can, and perhaps should, be measured by their capacity to encourage and enable the process of disrupting the continuity of the history of the victors with the memory of the vanquished and the nameless through political, cultural, spatial, and yes, architectural and artistic means. [3]

To work through the conception and design of memorial and democratic public spaces more generally requires a persistent attempt to work within and to transform the public domain in our contemporary cities. Cities have typically built memorials and historic landmarks that celebrate the memory of those they define as “heroes”. In so doing, cities have explicitly not created environments where the voices of the nameless and vanquished, the victims, witnesses, and “survivors” of today’s or yesterday’s crimes and injustices can be heard. At the same time, we should note that in our present – despite the Covid-19 pandemic where the other can be seen as source of contagion, as a source of fear – significant movements and protests against racism, as well as against forms of representation of oppression and oppressors, are taking place. As a very important example, the Black Lives Matter movement taking to the streets in the United States and around the globe strongly reaffirms and makes visibly visible that public space, and by extension the democratic public space, is indeed a space for assertion of political and cultural rights and of public appearance. In a powerful way and in defiance of fear, people all over the world, in solidarity with victims and survivors of past and present injustices, are standing with and close to each other acting as witnesses and agents of significant processes, protests and actions. These processes are effectively disrupting the ‘continuity of the history of victors’ and of many cities’ symbolic narratives. The dismantling, transformation and removal of monuments – erected in the past to support mythical and false versions of histories as well as to celebrate violent hegemonic figures – are clear manifestations that the fundamental struggle to establish a more just society, continues to play out in our democratic public spaces.

To continue this path and to accompany these public processes, I would like to suggest that, we, as artists, cultural agents and architects who want to deepen and extend the significance of the public domain have a twofold task: to create works and public programs that, one, help those who have been rendered invisible to “make their appearance explicitly” and, two, to develop citizens’ capacity for public life by asking them to respond to, rather than react against, that appearance. One such transformation, done a few years ago by my design partner, Krzysztof Wodiczko, is the Hiroshima Projections that transformed the remains of the Hiroshima A-Bomb site, into a ‘speaking and declaring monument’. Survivors proactively declare in public and through their projected testimonies ‘demand’ viewers to find ways to respond in and to the present.

Memory-Works: The Working Memorials

Engaging with the question of how history and histories, memories and traumas will be “appropriated”, “re-presented,” and “inhabited” and how these will be inscribed into the public domain and our built environment thus raises a whole host of issues that we should attempt to address: Can memorials work through and shed light over difficult memories, past and present injustices, collective traumas, while inviting the public to engage in the necessary transformative, pedagogic, healing and re-constructive work? Can we envision site-specific memorials that will frame collective and spontaneous acts of remembrance, will demand pro-active engagement, and will contribute to envisioning a better world? Architecturally and artistically, can or should memorials attempt to engage new generations and visitors in the search for memory, through the absence of direct signs, or overt metaphorical representation?

Such issues and complex questions (often without answer) call out for a conscious and humble approach as we need to be mindful and weary of the expectation of creating instant metaphors and artificial meanings. Given that often, and especially, in the wake of human catastrophes a “redemptive aesthetic” that asks us to consider art as a correction of life, emerges in the affected communities, it is important to constantly remind ourselves that neither art nor architecture can (nor should these practices attempt to) compensate public trauma or mass murder. What architectural and artistic practices can do is establish a dialogical relation with those traumatic events and contribute to frame the complex and often difficult process toward understanding and, perhaps, only perhaps, healing.

At the same time, I believe that upon conceiving and designing these projects (monuments, museums, memorials) we should be aware of significant risks, such as the objectivation of memory, the aesthetization of suffering or worse, its banalization. But these are risks that we should take, with care and respect, so that memory does not stay immersed inside but is affirmed in the public domain. Aesthetics should be at the service of ethics, and of life. As James Baldwin writes in “The Fire Next Time”:

“One must say Yes to life, and embrace it wherever it is found – and it is found in terrible places. … For nothing is fixed, forever and forever, it is not fixed; the earth is always shifting, the light is always changing, the sea does not cease to grind down rock. Generations do not cease to be born, and we are responsible to them because we are the only witnesses they have. The sea rises, the light fails, lovers cling to each other and children cling to us. The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out”.

The thesis or premise of this approach is those memorials that work – in other words “working memorials” – can foster and encourage new kinds of public engagement aiming to make the world a better place. Through various modes of perception, imagination, and experience these projects should serve to re-inscribe sites into the cognitive maps of cities and their cultural and physical landscapes. Their ethics, aesthetics, and politics should then articulate discursive, interrogative, pedagogical, emotional, and therapeutic potentials. Shaped by an awareness of the need to address a plurality of publics and generations these “working memorials” may become active agents for culture and dialogue, demanding responsibility and eliciting “response-ability”, human rights activism, and civic engagement.

A final (quite unfinished) note

I would like to suggest that working on such projects demands very precise, dialogic and committed attitudes towards design, towards techniques and materials, towards sites of memory, towards history, towards democracy, and especially towards the Faces and voices of others. It, thus, involves establishing clear critical-ethical frameworks to position ourselves as profoundly engaged and committed witnesses in our present and for our future. This approach involves inhabiting distance as one’s place for action – inhabiting the distance between act and remembrance, recollected worlds and worlds to be transformed. It entails asserting “presence” and “authorship” through a dynamic interaction and imbrication of conceptual and material worlds within (and without) the work, with the goal of ultimately effacing oneself and disappearing from the scene. This is the attitude, and the approach I bring to my teaching (in seminars, lectures, and design studios on memory and public space); to my design work for projects (see below), and to multiple endeavors and collaborations across disciplines (including EUROM, Radcliffe Institute on Universities and Slavery, and the Symbolic Reparations Research Project). It is an approach that involves understanding art, architecture, and landscape as mediums capable of shedding light over a limited set of truths and values in a space located between the questions, the publics, and the instruments of our practices. It involves attempting to contribute to the construction of a “democratic” and “agonistic” society, as authors, designers, architects, engaged witnesses and sentient subjects, through an ethics of deference to the “other” – that is, “moving out of ourselves”,¬ following Lévinas – when proposing transformative actions in the public domain.

In essence, what I would hope to suggest is, first, that we need to conceive a new approach to memory and memorialization in the public domain, one that understands memory as an action – a verb – rather than an object or a noun. Second, I believe we should attempt to broaden the understanding and sense of the word “memory” – which as a subject in the last few years of discussions about public space has come to mean, almost exclusively, evoking traumatic histories and events (this is a complex issue that should be further amplified and elaborated). Third, I think we should reimagine works and practices across many disciplines, including architecture, design, public art, and cultural activism, in relation to history and memory, with a renewed sense of public agency and purpose.

Memory-Works / Projects

Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery in Nantes, France

Wodiczko + Bonder

The Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery in Nantes, France was designed by our transdisciplinary-collaborative firm Wodiczko + Bonder, established by artist Krzysztof Wodiczko and myself to focus on art and design projects that engage public space and raise the issues of social memory, survival, struggle, and emancipation.

The memorial was commissioned by the city of Nantes in 2004, and opened to the public in 2012, with more than 1.5 million visitors to date. It entails a physical transformation and symbolic reinforcement of 350 meters (about 1,000 feet) of the coast of the Loire along Quai de la Fosse in the center of the city (Figure 6 -Nantes Esplanade).

As a metaphorical and emotional evocation of the struggle for the abolition of slavery – above all historic, but which continues into the present – it includes the adaptation of a preexisting underground residual space, product of the construction of the Loire embankments and ports during the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. It provides

space and means for: remembering and thinking about slavery and the slave trade; commemorating resistance and the abolitionist struggle; celebrating the historic act of abolition; and bringing the visitor closer to the continuing struggle against present-day forms of slavery.

By shedding light over difficult pasts and presents, both in Nantes and the world, and as an ethicopolitical, artistic, landscape, and architectural project, this unique urbanscape and memorial space has become an inclusive public space, and serves as an instrument for individual contemplation, an agent for collective conversation and a catalyst for transformative action.

National Holocaust Monument in Ottawa, Canada

Wodiczko + Bonder

This proposal proceeds through two fundamental, complementary gestures: exposure and immersion, which together create a layered, in-depth experience through which visitors discover and interpret both the history of the Holocaust and the memory of events which drove its survivors to Canadian shores. In this Working Monument, we literally propose to excavate the totality of the site to expose the limestone bedrock – found about three to four meters below the surface – thus creating a meaningful space below the level of the city, but open to the sky, in order to anchor new meanings, stories, and memories, in which visitors will find themselves immersed. Conceptually and formally, the project proposes: to reveal the bedrock beneath the surface; to provide a rich new soil inserted into the bedrock, and to plant groves of Aspen trees as symbolic reference to the cultivation of new life and memory; to provide a spatial experience of walking along ramps, downward, along and around the bedrock and the grove of trees; to visit the hall of names; and listen and watch the ‘eternal flame’ animated by especially recorded voices of the Holocaust survivors.

As an active and responsive public space, the project will include in its programming, narrative, and mission a strong connection to world events in the present. Rather than seeking to fix a particular memory in perpetuity, this monument will seek to respond to every generation’s need and will to remember. We hope visitors to the monument to be changed inwardly by their visit, just as the national Canadian landscape will be changed outwardly by the monument.

The Ripple Effects – Martin Luther King Jr. & Coretta Scott King Memorial, Boston

Wodiczko, Bonder, Thompson & Wood

The project, designed as a living memorial, has embraced the historic and unique task of creating a monument not to a single hero but to a partnership of two extraordinary people. The proposal for the Boston Common embeds this dual monument in a deep history of activism, signaled by the memorial to Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, and to carry that meaning and purpose into the future. This project proposes to both celebrate Martin Luther King & Coretta Scott King – their lives and accomplishments – as well as to invite present and future generations to see themselves as catalysts for an ongoing process of emancipation and transformation. The site organized by a mound on the east side and the Beacon Towers, on the west. They symbolize the continuing presence and inspiration of the Kings’ leadership, while at the same time – through the sound of specially designed bells and the pulses of light-monitoring – they continually inform visitors on current state of the emancipation process, globally, nationally, and in Boston.

This new public space and forum for engagement is created in order to inspire learning, dialogue, and activism now and later. It is not only a symbolic ground for public assembly, for civic celebrations, for cultural activity, individual and group reflection and discussion but also a socially engaging interactive environment, which – as an affirmation of life, love, fellowship and community – will embody a welcoming message, in and from Boston, for generations to come.

Footnotes

[1] Andreas Huyssen, “Introduction,” in Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003).

[2] Emmanuel Lévinas, Difficult Freedom: Essays on Judaism, Seán Hand, trans. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997)

[3] Examples include endeavors that seek reparative justice and symbolic justice, marches and public demonstrations, organizations that fight against present-day forms of slavery, mass incarceration and other forms of oppression, Truth and Reconciliation Commissions, the removal of monuments from Public Space, and many more. Other examples include artists and collective groups that contribute with their works to make visibly visible the nameless and the vanquished such as Alfredo Jaar, Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Marcelo Brodsky, Grupo Arte Callejero, Acción Poética, Jenny Holzer, Priscilla Monge, Benvenuto Chavajay, Forensic Architecture, Chto Delat, Muntadas, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, David Hammons, Elizabeth Alexander, Theaster Gates, Doris Salcedo, Tania Bruguera, Oscar Muñoz, Fire Theory, Regina Galindo, Anne Bouie, Jean-François Boclé, Martin Puryear, Hank Wills Thomas, Marilyn Nelson, among many others. Much of our collaborative work at Wodiczko+Bonder is based on these issues and questions.

Links

Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery, Nantes – Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery

Unearthing Traces of Rhode Island’s Slavery and Slave Trade – design studios

Radcliffe Institute Conference, Universities and Slavery: Bound By History – Universities and Slavery

Symbolic Reparations – Symbolic Reparations Research Project

References

Baldwin, James. 1963. The Fire Next Time. Dial Press Baird, George, 1995. “The Space of Appearance” – MIT Press – A discussion on Hannah Arendt and Public Space /Public Life

David Macey, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. 9–20.

Davis, Colin. 1997. Lévinas: An Introduction. Notre Dame, IN. University of Notre Dame Press.

DeKoven Ezrahi, Sidra. 2000. Booking Passage, Exile and Homecoming in the Jewish Modern Imagination Berkeley: U. of California Press.

Huyssen, Andreas, 2003. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lefort, Claude. 1988. “The Question of Democracy.” In Democracy and Political Theory, trans.

Lévinas, Emmanuel. 1997. Difficult Freedom: Essays on Judaism, Seán Hand, trans. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Young, James. 1993. The Texture of Memory. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.