David González, European Observatory on Memories (EUROM)

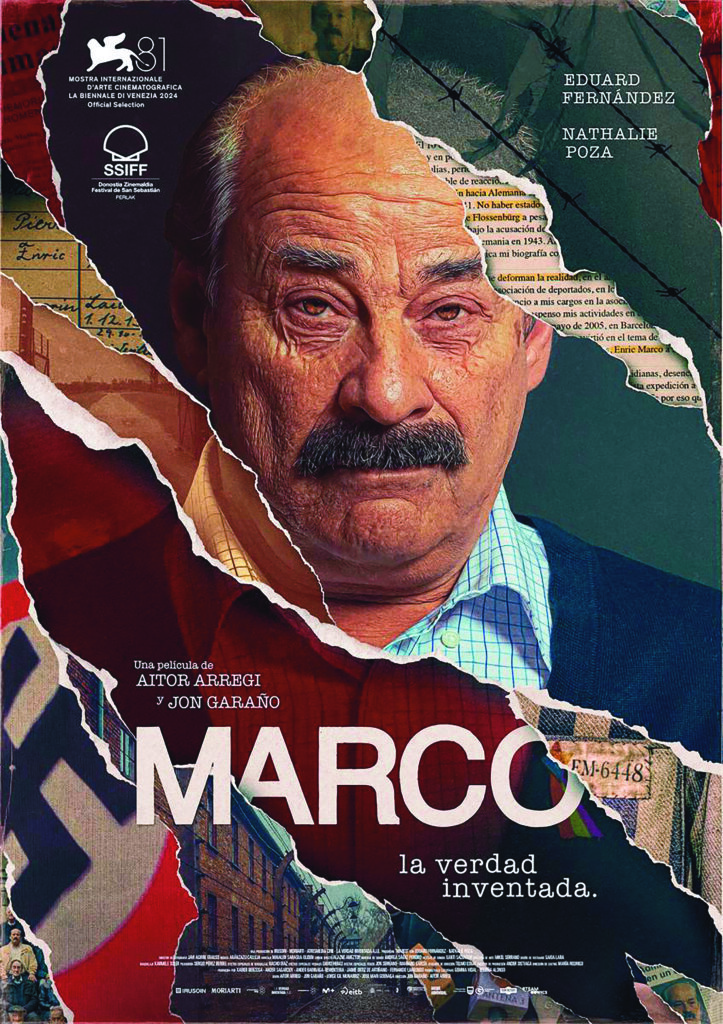

Marco (2024), directed by Aitor Arregi and Jon Garaño, is a drama that delves into the complex figure of Enric Marco Batlle (1921–2022), portrayed with great intensity by Eduard Fernández. For many years, Marco was regarded as a survivor of the Nazi camps—a false identity that he himself constructed and maintained publicly until it was revealed he had never been deported. The film, based on real events, explores this imposture and its ethical, social, and political implications, while also engaging with the human dimension of the character.

The cast also includes Nathalie Poza and Chani Martín alongside Eduard Fernández, with cinematography by Javier Agirre Erauso and music by Aránzazu Calleja. Its world premiere took place at the Venice Film Festival, followed by screenings in San Sebastián, before reaching Spanish cinemas in November 2024. The film was warmly received by critics and earned five Goya Award nominations, including Best Actor, which Fernández went on to win. It also received recognition at the Feroz Awards, and, although it was shortlisted to represent Spain at the 2025 Oscars, it was ultimately

not selected.

The story of Enric Marco, which forms the basis of the screenplay, is as fascinating as it is controversial. Marco claimed to have joined the anarchist militias during the first weeks of the Spanish Civil War, while still a teenager, although many of his accounts remain unverified. During the Second World War, he voluntarily travelled to Germany as a labourer, where he was briefly imprisoned, but never deported to a concentration camp, as he later falsely asserted. During the Spanish Transition, he became actively involved in the revival of the anarcho-syndicalist movement, serving as secretary general of the CNT between 1978 and 1979. He later participated in the parents’ associations movement during his daughters’ schooling, and in 2003, he was appointed president of the Amical de Mauthausen, the principal memorial association dedicated to Spanish deportees in Nazi camps.

His charisma, eloquence, and ability to connect emotionally with audiences earned him unprecedented media visibility. For years, he was accepted as a direct witness of the Holocaust, and his narrative became a powerful pedagogical tool for promoting memory and remembrance.

Particularly revealing is the film’s final section, where, after the deception has been exposed, Marco’s deepest contradictions unfold, along with his determination to continue presenting himself as a tireless fighter. The overlap between the fictionalised Marco and archival images intensifies the narrative, drawing the viewer into the last controversies surrounding his figure, especially his relationship with the media-savvy writer Javier Cercas. The revelation of Enric Marco’s imposture in 2005 had a profound impact on Spanish society—not only because of the deceit itself, but also because of the way it was used to discredit the broader memory movement. Conservative sectors exploited the scandal to question the legitimacy of efforts to seek justice for victims of deportation and the Holocaust, and, by extension, for those of Francoism.

From liberal circles, the case also created distance from the memorialist movement, and it was from this perspective that Javier Cercas later portrayed Marco in his non-fiction novel El Impostor (2014). Cercas’s work revived the case and brought it back to the centre of public debate. Although praised for its literary quality, it was also criticised for its inquisitorial tone and for a problematic equidistance between conflicting memories. For many, the book simplified the memorialist phenomenon and discredited it from a position of moral and intellectual superiority.

The scandal affected not only Marco’s personal reputation but also dealt a severe blow to the Spanish memory movement. The revelation that one of its main spokespeople was an impostor undermined public trust and gave ammunition to those who already doubted the legitimacy of such initiatives.

The association Marco had presided over, the Amical de Mauthausen, was particularly affected. Rosa Torán, who later served as president of the Amical, reflected on the complexity of addressing an issue that went far beyond an individual act of deception. As a historian, she herself consulted the Flossenbürg archive, but could only access prisoner records up to the letter F, since many documents were dispersed after the camps’ liberation. Moreover, although exhaustive studies exist on Spanish deportees in Nazi camps, there is almost no information about those deported from within Germany itself—the group Marco falsely claimed to represent.

In fact, not a single documentary proof could ever be provided to demonstrate that he had not been in Flossenbürg. It

was the persistent research of Benito Bermejo that ultimately forced the truth into the open.

The case of Enric Marco represents a paradigmatic “glitch in the matrix” of the Spanish memorialist movement. His imposture opened a deep fissure in the credibility of a movement that had spent decades striving to recover the silenced voices of the deported. Although Marco claimed to have acted with good intentions, the damage he caused was profound and lasting. His life—oscillating between truth and fiction—remains an uncomfortable mirror of the tensions between history and memory, and of the deeply human contradictions of someone driven by an overwhelming need for recognition.