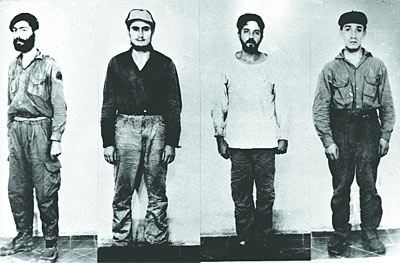

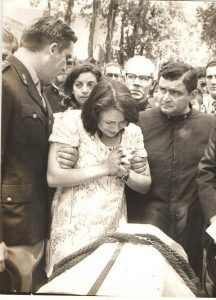

Picture: Members of the Ejército Guerrillero del Pueblo in Salta, 1964 | Revista El Sur

By Leigh A Payne, Latin American Centre, Oxford School of Global and Area Studies

What happens when armed left guerrilla or revolutionary fighters confess to past violence? Can they contribute to building stronger democracies or human rights cultures? Are they in any way similar to confessions by perpetrators of state violence?

Some parts of my earlier work on state perpetrators — Unsettling Accounts – carries through to this new study on Left Unsettled. The revolutionary left and state perpetrators, for example, make confessions that are unsettling in content, specifically terrorist violence against civilians and extreme violence against their own comrades. Like state perpetrators, confessions on the left sometimes break or unsettle, a silence over left-wing involvement in past atrocities. When the left speaks out – like the right–, they do not settle accounts with the past but unsettle them. Confessions by the armed left disrupt a narrative that has settled about that past, that is, the left as innocent victims, and not perpetrators, of atrocity. The term ‘left’ in the title of the new project refers in part to the stated ideology of the revolutionary groups; but it also refers to what is ‘left out,’ or silenced from memory politics, what remains or is ‘left behind,’ in the analysis of past violence.

The earlier project suggests that despite the unsettling nature of the confessions and the near impossibility of reconciliation as a result–, engagement of the audience can nonetheless positively benefit democracy and human rights through “contentious coexistence.” Dialogic conflict over past violence puts into practice the very values of democracy–participation, expression, and contestation—that sharpens, refines, and promotes widespread support for human rights norms. The earlier book comes to this conclusion by developing a dramaturgical approach. It is not that the confessional text (script) alone can have a positive effect on democracy and human rights. Indeed, certain texts (e.g., heroic or sadistic ones) can have the opposite effect on their own. Instead, other elements of the confessional performance – the perpetrators themselves (actor and acting), the political moment (timing), the space of the confession (stage), and the audience – can turn even these potentially harmful confessions into positive outcomes

That positive effect is not a typical outcome for armed left confessions, however. Instead, fearful of how the right-wing might exploit these confessions to demonize the left, silencing and not contentious coexistence has resulted. Yet one factor that may contribute to a positive outcome is timing.

This article considers timing as a factor shaping the impact of left confessions on democracy and human rights. It looks at two different historical moments in which the armed left confessed in Argentina. The more recent set of confessions occurred during the presidency of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Two former members of the armed left made public written confessions, followed up by televised interviews, about their past, condemning the acts of violence in which they had participated. Claudia Hilb was a former student militant who confessed after she had become a professor at the University of Buenos Aires. Ricardo Leis was a Montonero leader who confessed as a Philosophy professor, living in Brazil since his exile there in the 1970s. They both called for a reckoning of the violations of human rights by the left to build a stronger democratic and human rights culture in Argentine politics. They both desired an end to the glorification of violence and the use of violence as a legitimate political tool. They both called for a rejection of human rights violations by whoever engaged in them, regardless of perpetrators’ ideology. The response was silencing. The timing or political moment was not propitious for debate about the leftist past. This was a time of heightened political polarization in Argentina, a strong right-wing ‘anti-Cristina’ mobilization, and an effort by the right to attack the human rights trials underway in the country as one-sided. The confessions were seen as either a call for “justice for all,” which would mean putting the left on trial after it had already been decimated through torture, disappearance, exile, and extermination during the dictatorship, or “justice for no one,” which would undermine the ongoing trials of perpetrators of state violence. The analysis of that particular political moment suggests that confessions on the left cannot achieve the positive role of contributing to democracy and human rights and might even cause set-backs in those processes.

Yet, an earlier confessional moment had a different outcome. They did not engage the right-wing. There were no efforts to silence them. Instead, contentious coexistence emerged among the left in which different individuals, sometimes within the same armed left group, took positions on the past and openly – and sometimes harshly – engaged in a dialogue about the violent past. This debate began at the end of 2004 on the pages of the Córdoba political left magazine (La Intemperie) and was later published in part in a book called No Matar. The dialogue began with an interview of the former member of the Ejército Guerrillero del Pueblo (EGP), Héctor Jouvé. Jouvé explains that he joined the armed left due to an intellectual commitment to end poverty and injustice, and his awareness that mainstream political parties lacked the will to bring about change. He expresses regrets about that past, however. In particular, he has misgivings about an acceptance on the armed left of authoritarian leadership and its abuses of power. He uses as examples the executions ordered by the leaders of the movement of two rank and file members (Adofo Rotblat “Pupi” and Bernardo Groswald). Jouvé takes responsibility for witnessing those acts and failing to speak out against them. He thus became, in his view, an accomplice to murder. His confessional text calls for language, speaking out and asking questions, as a political weapon: “culture is a web of conversations…more than defining ourselves, we need to ask good questions…if not, we will continue to repeat the same mistakes.”

His words begin a dialogue. Oscar del Barco wrote a letter stating that Jouvé’s interview “moved” him to become conscious, albeit very late, of the serious tragedy within the EGP. He says, that “by supporting the activities of this group, I was as responsible as the murderers.” He goes on to say, “There is no explanation that makes us innocent.” There are not causes or ideas that remove our guilt. He calls on everyone to accept the command “thou shall not kill,” to recognize that all human beings are sacred, that no one, no matter what they did, should be killed. He refers to the left around the world (Russia, Romania, Yugoslavia, China, Korea, Cuba), as failing to uphold this command, and, as a result, becoming “serial assassins.” He calls for ending the silence about the left’s involvement in atrocities, “truth and justice should be for everyone.”

Del Barco is not silenced. A deep dialogic conflict erupted instead. For some the issues that Jouvé and del Barco exposed were not new. As one commentator states, “Nothing said is new to me; but it has a particular intensity.” For others what emerged was “previously silenced themes and problems.” The aim of the magazine and those who confessed, to generate debate and contention over the past within the left succeeded on the pages of subsequent issues of the same magazine and in other news outlets.

On the positive side, those who supported Jouvé and del Barco mentioned how their confessions played a role in presenting a more nuanced version of the past that fell in between the existing narratives of the left as in the two devils theory or a devils-angels theory. The confessions emphasized the danger when the movements’ goals and its actions are disconnected and inconsistent. These supporters further embraced a commitment to the commandment “thou shalt not kill” on the left and the right to end the legacy of violence as a way to do politics. Finally, these supporters identified the value of talk, dialogue, speaking out, as the best weapon in the war against political injustice.

Those who criticized these confessional acts, concentrated on del Barco’s text. Some agreed that mistakes were made by the left, but they felt that del Barco went too far in demonizing the whole left for those mistakes, particularly in the reference to “serial assassins.” A common criticism was the view that del Barco constructed a moral equivalency between the violence on the left and right. In particular, the confessional text emphasized a few terrible events on the left that creates a twisted version of the past (“una moral distorsionada”), more likely to politically polarize society rather than find common ground. The notion of “thou shalt not kill,” moreover, is on the surface unimpeachable, but fails to recognize how throughout history violence and counter-violence was required to address gross injustices. The very independence of Latin America from Spain’s tyranny depended on a willingness to kill and be killed. To reduce the struggle of the armed left to the act of “serial assassins,” furthermore takes away the dignity of those who sacrificed their lives for a better world, turning them instead into “senseless deaths” (“muertes sin sentido”).

This contentious debate could be seen as healthy for democracy, putting into practice its essential elements of political participation, expression, and contestation. It could be said that Jouvé and del Barco achieved their goal by stimulating dialogue, the art of doing politics through talk, speaking out, raising difficult questions, critical analysis, and overcoming authoritarian adherence to a single perspective.

Why was contentious debate over the left’s violence possible in the past and not in recent years? One of the historians who participated in the debate focused on the political environment in 2004-2005 when the news media focused on these confessions. He argued that the period of time was less threatening than in the years following the transition. The climate was more conducive to open and public debate than in those earlier times. In addition, there was a catalysing moment, a triggering event, that those on the left responded to in different ways. In the texts, references are made to a Mariano Grondona television program in which a widow of army captain Viola speaks of the cruelty of the People’s Revolutionary Party (ERP) in killing her husband. Grondona evoked – “without any subtlety” — the image of the two devils. This highly contested view of the past promoted by the authoritarian regime was back in circulation. Rather than simply rejecting it out of hand, in this less polarized moment, those on the armed left who had engaged in or witnessed cruelty by their own forces were willing to take a moral stand against it.

Another part of the debate focused on a different aspect of the political moment. This debate followed the “que se vayan todos” (“throw the bums out”) protests in which a majority of Argentines took to the streets against politicians. Argentines were claiming their voice, their citizenship, their right to have rights. In this context, the closed and unresponsive state was challenged. It is in this context that the authoritarian regime of the past is identified as a terrorist state, and not merely a dictatorship. Thinking critically, challenging top-down views, questioning authority, became part of the political climate of the time. A period of democracy in the streets that seemed to have a contagious effect among the left. Some were willing to reflect on the hierarchies within their own movement that had lost touch with the base, the rank and file, and the goals of social justice, where ends justified means.

Despite this propitious political moment, there were still efforts at silencing these unsettling truths about the left. Some suggested that del Barco himself had closed off the possibility of dialogue through his use of “unbridled violent language aimed at all protagonists” on the left. Because of this, some on the left called for censoring del Barco.

Another form of silencing occurred with the publication of the book No Matar. The book was meant to present the full contours of the debate triggered by Jouvé’s and del Barco’s confessions. Certain positions in that debate were excluded from the publication, however. In particular, those who agreed with Del Barco were left out. One had criticized del Barco’s critics, referring to their positions as using “historical contingency” to excuse past violence by the left. Another excluded part of the debate questioned the view of the left’s “mistakes.” This view contended that “executions are not errors. They tend to follow a long period of planning.” Another excluded commentary was one that shamed the left for “hiding in silence” about its use of violence, responding not to their moral duty but their fear of the right’s exploitation of these truths.

This brings me to my conclusion. Political timing is important, even crucial, to contentious coexistence. The other elements of the confessional performance did not vary much between the two historical moments. Hilb’s and Leis’s confessional scripts resembled the earlier ones by exposing unsettling aspects of the armed left’s past violence. They were similar kinds of actors, having been members of the armed left who had witnessed atrocity. Their confessional stage was not significantly different. They too had published their texts and were interviewed in the media. The audience – the right and the left – were similar in each set of confessions. The main difference that helps us explain the possibility of opening up debate is the timing of the confessions. The earlier period was a safer moment for the left to admit to these atrocities without the same level of fear about backlash.

But even in the most propitious moments, as in the earlier confessional era, there is still too much polarization to freely debate the left’s violent past. As one of the commentary’s states about the confessions, “They unsettled me.” Yet one of the most unsettling parts of the confessional performance for him was the failure on the left to hear. As he stated, “We have opted not to listen.” Thus, even when a debate is opened up, there is an effort to shut it down. In this, the left has failed to live up to its own ideals and theories, to think critically, to reflect, to condemn those parts of the left’s past that deserve condemnation.

If it is the case that even in the best of times, left confessions to violence face silence, what does this mean for contentious coexistence? If even during the periods of a broad consensus to reject violence as a way to do politics, the left cannot reflect on its own role in the past, then what are the possibilities of building a strong, democratic, peaceful future that respects human rights? More poignantly, during the current period, as Latin American countries move further away from the left, and the right is empowered, can debates render the kind of contentious coexistence that is positive to democratic dialogue and building a stronger human rights cultures? Or will they provoke a further rollback of rights and the delegitimization of the left? Is there a way in which the left can play a constructive role, in these unpropitious and propitious political environments, in building stronger human rights regimes?

Timing has never done all of the work of turning confessional performances into contentious coexistence and democratic practice. How timing affects audience responses is significant. Until audiences on the left feel it is safe to talk freely about the past – without fuelling political polarization and playing into the right’s efforts to demonize the left – it is unlikely that these confessions will have their intended effect of rejecting violence as a political strategy. And yet without broad consensus against the use of violence by the right or the left, it is uncertain whether countries can emerge from the legacies of the past and build democratic and human rights futures.