By Diana Castelblanco, Professor at the Jorge Tadeo Lozano University in Colombia

In his work Voices from Chernobyl (2015), in the chapter ‘Monologue on Why People Remember’, the Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich presents us with the testimony of the psychologist Piotr S., who asks, why do people remember? “Is it to restore truth? Justice? To free themselves and forget? Because they realise they have been part of a great event? Or because they seek some form of protection in the past?” This is the account of an ‘ordinary’ man, reflecting on one of the human tragedies that, beyond the intention to quantify it through the force of its death toll, impacts as profoundly as the Holocaust, the repression and disappearance of people during the civil-military dictatorship in Argentina, or the more than nine million people recognised as victims of the social and armed conflict in Colombia.

While statistics shake our collective conscience, they also overshadow the individual stories behind these numbers, diluting our understanding of the human condition imposed in such circumstances. A story, a singular voice, among others, resists oblivion by unearthing images from the past, images that appear with overwhelming force in the present, reminding us that in the contest over numbers, the profound meaning of what has been lived must not be lost.

But what does it mean to remember? It is to have an image of the past. How is this possible? Because this image is a mark left by events, one that remains imprinted on the spirit. “The truth is that when we recount true events from the past, what we draw from memory are not the events themselves, but words created by the imagination, imprinted upon the spirit like marks engraved on the senses as they pass by” (Ricoeur, 1996, p. 44).

So, how do we tell what has happened to us?

In the case of Colombia, “testimonial narratives have been so numerous that one volumes of the Final Report of the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, for Coexistence and Non-Repetition – CEV – (2022) It was dedicated to these words created by the imagination. This volume, titled Cuando los Pájaros No Cantaban: historias del conflicto armado en Colombia (When the Birds Didn’t Sing: Stories of the Armed Conflict in Colombia), is also known as the Capítulo Voces del Informe final. (Voices Chapter of the Final Report).

By listening to victims, perpetrators, and other involved actors, the Commission identified a narrative structure where the everyday emerged as a prominent aspect of the war. The history of the conflict was made up of “stories within stories”, that is, fragments within narratives that recounted life, subjectivities, and intimate experiences of violence. An everyday structure wrapped in time as a triple present: “a present of future things, a present of past things, and a present of present things” (1996, p. 124). A kind of temporal indeterminacy of memory, as it appeared in a present from which the past was remembered, while simultaneously being a present from which the future was envisaged. In this way, victimising acts were addressed not only from the traditional approach of “listening as a gesture of the past,” focused on specific moments of violence, but also incorporated a future perspective, considering the expectations regarding the processes of truth, justice, and reparation to which the Colombian State committed itself, within the framework of the Peace Agreement signed between the National Government and the FARC-EP (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—People’s Army in 2016.

(…) this volume sought to compose a polyphony of the war through the most intimate experiences of those who lived it. It therefore focused its efforts on delving into the memories of violence using a narrative that connected a past which, in tangible terms, has not been left behind- since violence continues in Colombia – an uncertain present, and a “future” imagined from that uncertainty and through efforts to build “peace on a small scale” (2022, p. 9)

Thus, the stories of violence and their images became traces left by past events, an interpretation of experiences in the present, and a sign with anticipatory meaning about the future as a possibility. Cuando los pájaros no cantaban recounts the tragedy and the circumstances that preceded it; it tells of the silences and absences that pervaded the experience, as well as the traces and scars it left behind. However, these are also stories of life; of people’s efforts to imagine, from their present, a future as a possibility, which, according to the Truth Commission, seems elusive in Colombia. The Testimonial Volume is divided into three books: El libro de las anticipaciones (The Book of Anticipations), El libro de las devastaciones y la vida (The Book of Devastations and Life), and El libro del porvenir (The Book of the Future).

Below are a few fragments from these stories, among the more than 150 compiled in this archive:

“Like a Revelation”. A woman recounts dreams and visions of the Virgin that warned her of armed groups entering her territory (2022, p. 73)

This testimony speaks of the fear of forced recruitment of minors by paramilitaries and of forced displacement as the only alternative to protect oneself from clashes between armed groups.

“The River is Not to Blame A Black woman, part of a victims’ organisation, explains that the river is not to blame for the paramilitaries making it complicit in the war. (2022, p. 137)

In this testimony, the river, used by perpetrators to hide bodies, symbolises the social, cultural, and environmental impact of the conflict. Its transformation into a place associated with violence and loss, interrupting everyday practices like fishing and water use, also reflects the processes of displacement caused by the conflict.

According to the Commission, in this volume, testimony is defined as an “articulation of experience”, where personal and social processes intertwine. This concept of articulation not only includes the use of words but also extends to visual and poetic languages – symbolic, textual, performative, and object-based representations – that form a tapestry of “textures of experience” from which to try to “understand the social processes through which the public image of the past is constructed” (Jelin & Vinyes, 2021, p. 9).

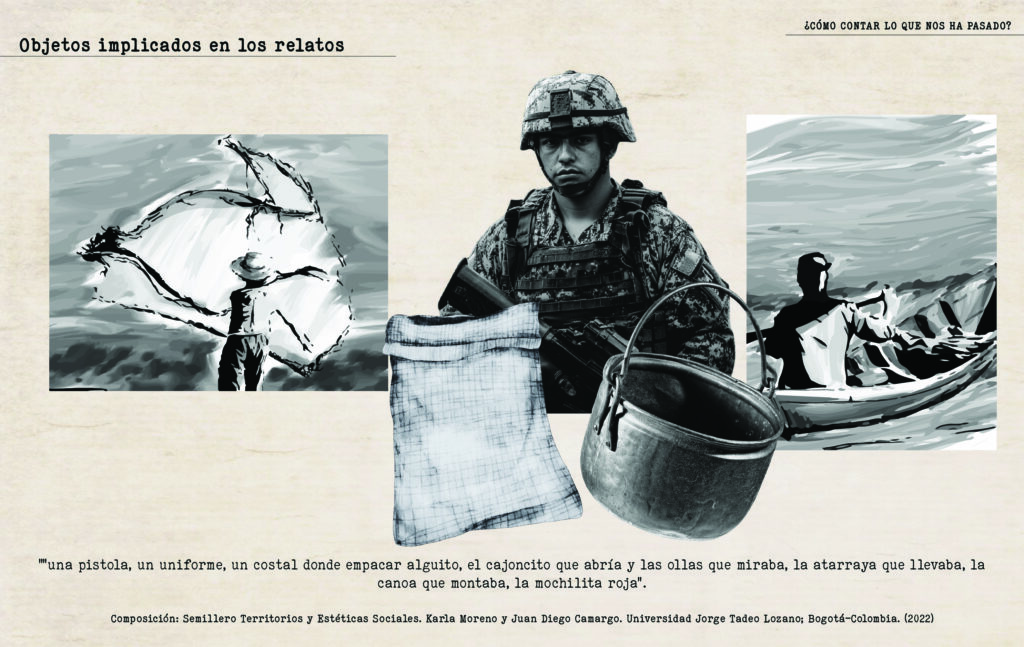

It is important to highlight that people do not only testify with words but also through the objects involved in their narratives: “a gun, a uniform, a bag to pack a few things, the small box they opened, the pots they looked at, the fishing net they carried, the canoe they rode, the little red backpack” (cover image).

These are images that enrich and deepen the testimonies, attending to “a piece” of reality and “an interest” of the one narrating that reality. Objects, while understood as a singular voice, give us access to the historical, territorial, and differentiated reality of the conflict in Colombia, as they speak, more than about themselves, about how we can understand the social world in which they are situated. These are cultural expressions – images – in which versions of the past and events associated with places and communities are contested. It is an approach to history “from below”, not only because of who narrates but also how that past is narrated: a narration in the key of everyday life.

Those who tell their stories hold onto objects to organise their memories in a coherent, lasting, and stable form where the past can reside. The focus is less on explaining the facts than on making sense of that past in order to understand it, as the objects provoke and evoke a sensitive attitude towards human experience. Objects present in the physical spaces of daily life; absent objects, remembered and narrated through words; objects that represent intimate expressions intimate expressions that oscillate, move, flee, and return in an apparent disorder, with an intense range of emotions: passions, hatreds, attachments, fears, arrogances, disappointments, desires, liberations, or reprisals (De Certeau, 2000).

In these stories, the objects are numinous in the sense described by Rudolf Otto (1991), as they suggest a mystery, evoke terror and fascination that delve into the depth of memory, the experience of the past, and the expectation of the future. They are witnesses that survive time, while also acting as provocateurs of testimonial practice – of words – and thus of memory and remembrance. “The past – what is absent, what has ceased to be – returns, embodied in the object that vectors both words and gestures” (Avila & Landa, 2022).

Carlos Martín Beristanin, advisor to several truth commissions in different countries and a commissioner in the Colombian Truth Commission, said that “objects symbolise the relationship with origins, ancestors, the founding myths of collective life, a type of debt to those who are no longer here” (Beristanin, 2021). There are also memories in objects, as the Commissioner said when referring to the uniqueness of the Colombian conflict; to the differential, ethnic, and territorial approach that was adoptedduring the peace negotiations between the National Government and the FARC-EP (2016).

In the interest of reconstruct these territorial narratives, focusing on the victims and recognising the ethical and aesthetic dimensions of the of the communities, The Truth Commission created the Fondo Documental de la Colección de Objetos de la Memoria (‘Documentary Fund of the Memory Objects Collection’). This archive represents the memories of victims of the armed conflict in regions such as Cauca, Casanare, Caquetá, Córdoba, Guaviare, Huila, Meta, Nariño, Santander, and Valle del Cauca, among others. It comprises more than 100 objects donated to the Commission by victims or members who have led social processes of denunciation or reparations for the damages caused by the war for many years. The objects stand as memories of the wounds left by violence in these regions and represent territorial memory, referring to the experiences that evoke origins, identity, and the community, in line with the so-called “differential approach to the Colombian conflict”.

The stove: The fire pit is a significant object at the Truth House, where gatherings were held. This fire pit was built with the intention of bringing people together around food to talk about their experiences of the war. Buenaventura, Valle del Cauca, Colombia. 2 November 2021.

Archive: Juliana Sandoval, curator of the exhibition “Objetos sagrados, palabras preciosas” (Sacred Objects, Precious Words) at the Centre for Memory, Peace and Reconciliation, Bogotá-Colombia. (2022).

Basket of veins: During the process “Women Speaking and Doing: Justice, Search and Truth,” a basket was collectively woven. As they wove, the women reflected on the impacts they had experienced, both personal and collective, how they faced them, and what should be done to prevent their recurrence. The basket, a traditional handmade object used by Afro and Indigenous communities in their daily activities, symbolises these reflections. Buenaventura, Valle del Cauca. 2 November 2021.

Archive: Archive: Juliana Sandoval, curator of the exhibition Objetos sagrados, palabras preciosas (Sacred Objects, Precious Words) at the Centre for Memory, Peace and Reconciliation, Bogotá, Colombia (2022).

Catumare:The indigenous delegates from the Caño Negro and Cachiveras de Nare reserves in Guaviare presented an empty catumare as a symbol of their waiting for the remains of members of their community who joined armed groups and have not returned. In their tradition, when one of their leaders dies, they are buried in the maloca, and in the fifth year, a celebration is held where their remains are painted and placed in the catumare. After three days of commemoration, they are buried permanently. San Jose del Guaviare, Guaviare. 19 November 2021.

Archive: Archive: Juliana Sandoval, curator of the exhibition Objetos sagrados, palabras preciosas (Sacred Objects, Precious Words) at the Centre for Memory, Peace and Reconciliation, Bogotá, Colombia (2022).

Travelling Letters: On 1 September 2021, the Truth Commission held the Living Action Cartas Ambulantes (Travelling Letters) at Loma de la Dignidad in Cali, an artistic event that highlighted the impacts suffered by the university community during the armed conflict, promoting truth clarification and non-repetition. Seventy-four testimonies were typed on typewriters, with the participation of 45 people. Cali, Valle del Cauca. 19 November 2021

Archive: Archive: Juliana Sandoval, curator of the exhibition Objetos sagrados, palabras preciosas (Sacred Objects, Precious Words) at the Centre for Memory, Peace and Reconciliation, Bogotá, Colombia (2022).

In commemoration of the National Day of Memory and Solidarity with Victims, on 9 April 2022, the exhibition “Objetos Sagrados, Palabras Preciosas” (Sacred Objects, Precious Words) was presented at the Centre for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation in Bogotá, Colombia. There, some of the Memory Objects were displayed, accompanied by the narratives that the victims and social leaders constructed around them. By being integrated into the context of the exhibition, these objects move away from their original use to form a new social device that defines what and how to remember what has happened to us (Guglielmucci, 2021).

Exhibition “Sacred Objects, Precious Words” at the Centre for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation, Bogotá-Colombia. (2022). Taken from: https://www.elespectador.com/el-magazin-cultural/la-suma-de-las-voces/en-los-objetos-tambien-hay-memorias/

These objects are representations of memory to denounce human rights violations, to resist forgetting, to recognise oneself as a victim, to reaffirm identity, to reconstruct events; in general, to evoke an image of the past. An image which, in the Colombian context, is associated with a specific form of war: deterritorialisation and loss of identity. Everyday objects like a pot, a cast net, a basket, or even abandoned houses, not only represent the political reality of forced displacement but also reflect social relationships and personal experiences, where words like “abandonment” and “loss” are part of the fabric of the experience that led to fragmented identities and torn communities.

Exhibition “Sacred Objects, Precious Words” at the Centre for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation, Bogotá-Colombia. (2022).Archive: Juliana Sandoval, Exhibition Curator

So, how do we tell what has happened to us?

Words and objects bring us back to the idea that remembering is an attempt to make sense of experiences that are difficult to fully narrate. However, lived life and narrated life are not the same (Ricoeur, 2006). The stories we tell do not always capture the entirety of lived experience, yet they are essential in trying to understand and humanise our experiences. Objects, together with words, face the challenge of dealing with the inassimilable. Their function is not merely to restore the original context but to create a new environment, woven with a connection more metaphorical than contiguous with the fabric of violence. Sometimes, these objects make visible microhistories, in Ginzburg’s sense (1994), singling out details from subaltern subjects to achieve surprising representations of what has traditionally been rendered invisible in historical accounts, “the ruins of the social”. At other times, they are configured as metaphors that replace the focus on “the real” with an aesthetic value that reworks the grand narratives of the past or empowers those narratives to formalise a historical account.