Pavel Tychtl

Representative of the European Commission

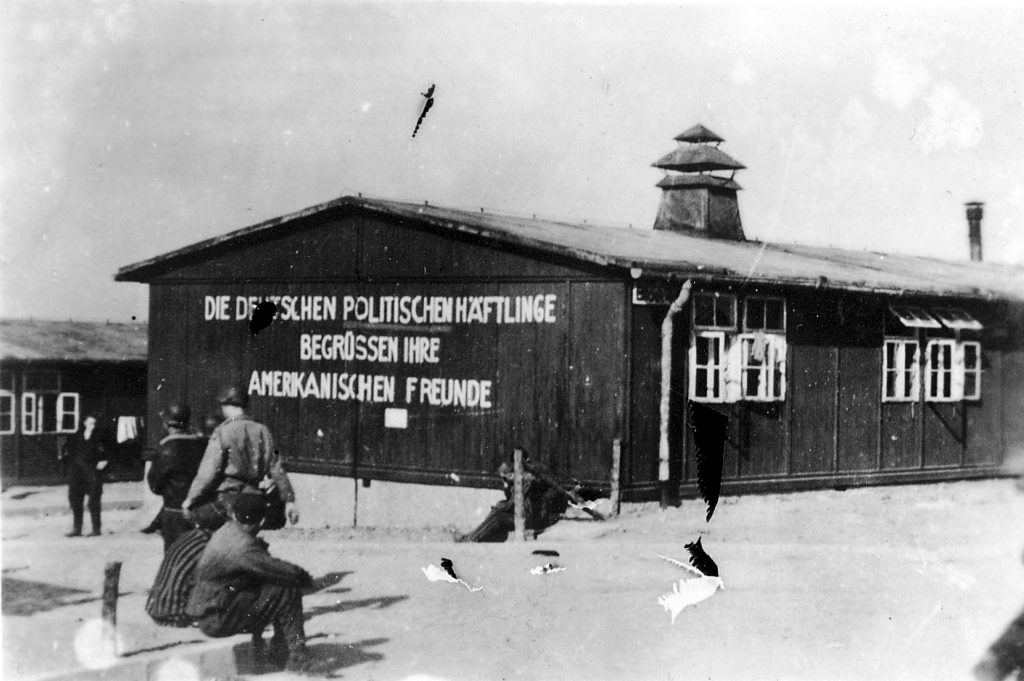

There are two stories that illustrate well the many complex issues connected with memory. Both of them are linked to one place with a very specific role in the memory of the 20th century. The place is the concentration camp of Buchenwald and the first story is from the book by Jorge Semprún who came to Buchenwald because of his activities in the French resistance movement. Shortly after the liberation, Semprún goes to a house which stands close to the concentration camp, close enough so that the inhabitants of the house were likely to witness what has been going on in the concentration camp before the liberation. He comes to the house and meets with its only inhabitant, a scarred lady who doesn’t resist when he invites himself in. Semprún walks through the house and a certain point reaches the living room with the window which provides an unobstructed view of the concentration camp. Semprún now understands that the lady must have seen from her living room everything that was taking place in the camp but doesn’t seem to be troubled by it. Instead she points at the photograph of her sons who have fallen in the war. Her memory and her morality do not stretch beyond the point of her living room and that of her family.

The second story is that of the “Blind hero of French resistance” as he was referred to in somewhat Hollywood style in the United States where he moved after the end of the World War II. It is the story of Jacques Lusseyran who lost his eyesight when eight years old and who at the age of seventeen created a resistance network Les volontaires de la Liberté. He was betrayed, interrogated by Gestapo and finally sent to the concentration camp of Buchenwald. He was one of the thirty who out of two thousand originally deported survived until liberation. After the end of the war he moved to the United States and taught literature at the University of Hawaii. In 1971 when together with his wife he visited France he died in a car accident in the very region where he spent his childhood. The local French press referred to the victims of the accident as “two foreign visitors from Hawaii”.

It seems clear that the first example suggests that memory is selective and the fact of physical proximity doesn’t provide foundations for an eyewitness account. It is also possibly an example of denial and – in long term of forgetting.

Forgetting seems to be the main element of the second story as well – hero of resistance forgotten in his own country. But it seems to be more than that. The metaphor of the “foreign visitor” could be well applied to the individual and possibly also collective link to historical memory. When entering the territory of memory the choice is between that of selecting the “evidence” for one’s interpretation of the past and excluding the bits which would contradict that interpretation. The other choice is of acting as a foreign visitor who enters with the “Veil of Ignorance” open to re-negotiating his or her relationship to the past and as a result ready to re-negotiating his or her very own identity and accepting that the identities can be contradictory. The former is the story of a living room window facing the concentration camp; the latter is an experience of forgetting but also of transformation and change.

The foreign visitor enters the land of memory with the feelings of an impartial observer, detached from the local and the specific, even if not free of all feeling. Human universality is his main compass.

When travelling in the land of memory, the foreign visitor comes across signposts which promise to help him to find the right direction. But when taking a closer look at these signposts the visitor finds out that the signposts do not have one clear and single meaning. When one of the heroines of the German television series “Heimat” comes to the town close to the concentration camp Dachau where supposedly her Jewish mother had been taken during the war, she finds out that the town square is called the Square of the Resistance. How is this to be understood? Is the name of the square to be seen as a tribute to the very few who resisted the Nazi regime or is it to be seen as a façade, a smokescreen to hide the less glorious past? Along the way more signposts with similar ambiguity appear – the foreign visitor has to trace and read three memorial plaques before he understands that the bridge of the Nibelungen in Linz was built from the stone which came from the stone quarry in which the prisoners of concentration camps of Mauthausen and Gussen were enslaved. The visitor has to search in the back of the car park in the Czech town of Tabor to realise that this is where once a Jewish synagogue stood before it was pulled down in 1978. And sometimes there are now signposts at all such as in the case of mass grave of Roma killed during the Second World War in Ukraine or Belarus in the fruit garden of now an old lady. Then the visitor comes to the conclusion that in the land of memory the signposts mark no end of the journey.

There are many reasons why people become interested in history. In the countries which in the past were situated east of the Iron Curtain some found interest in history as they thought it would liberate them from the bleak realities of their situation of “captive nations”. Their history was the history of the oppressed. Once the Iron Curtain fell, the former captive nations entered a new world but soon felt marginal and history has become a means of compensating for their perceived peripheral status and the shortcomings of the present. It was the history of the marginalised and disappointed.

The second story, is a story of return to the familiar and yet unknown. We explore the nature of memory with eyes of a foreign visitor to be surprised and to be transformed at the end. As a result we come from the history of the oppressed and marginalised to the history and memory of free people. Finally, history will liberate.