Orli Fridman, Faculty of Media and Communications (FMK) & School for International Training (SIT)

In these times of new media ecologies and hyperconnectivity, hashtags have become an integral part of our everyday communication. The hashtag symbol (#) is often used as a way of marking a conversation on social media platforms. Hashtags can function like a filing or retrieval system when looking for updated news on unfolding events.

In recent studies of digital protests and digital activism, attention has been given to the hashtag symbol, suggesting that the hashtag itself can become a field site (Bonilla and Rosa, 2015). Hashtag activism emerged as an important category of analysis, since online social platforms now function as sites of activism for various issues worldwide. Among some of the most prominent current examples are hashtags such as #MeToo, in the fight for gender equality, and #BlackLivesMatter, in the struggle for racial justice. Hashtag activism, as opposed to routine hashtags, has a recognisable narrative form with a beginning, a crisis/conflict, and an end (Yang 2016). In many influential cases of hashtag activism, hashtags appear in the form of complete sentences rather than single words, as in the cases of #JeNeSuisPasCharlie, #MuslimsAreNotTerrorists, and others.

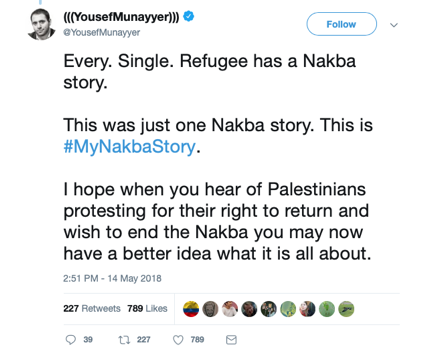

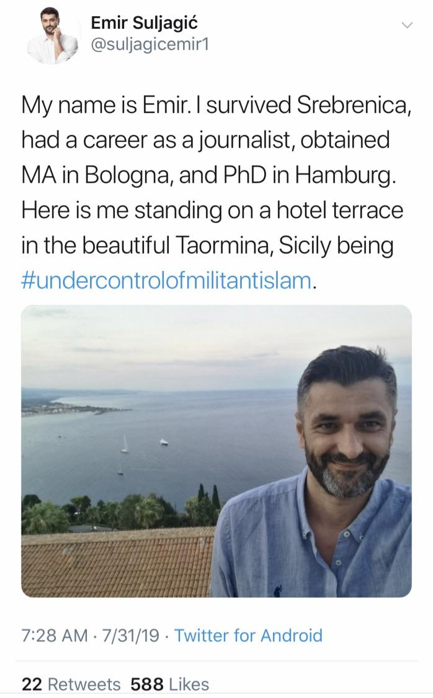

In the new digital ecology of participatory media, digital media users take a stand, interact, show their disagreements, and condemn or support daily occurrences, politicians’ statements, and recent news. They rapidly produce content, communicate back, share, like, tweet, and retweet. A review of some prominent Balkan-generated hashtags in 2019 reveals this dynamic. To mention only a few: #literallyjustemergedfromthewoods appeared in May 2019 in the communications of many digital media users from Kosovo and the Kosovar Albanian diaspora following a comment made by Serbian PM Ana Brnabić, who referred to Kosovo’s leaders as people who “literally just came out of the woods.” Over the next days, hundreds of users uploaded and posted their images, with comments and the hashtag itself, which marked the discussion and the reactions to the PM’s statement (see image 1). Similarly, in reaction to a comment made by Croatian President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, who on her official state visit to Israel in July 2019 allegedly referred to neighboring Bosnia-Herzegovina as an unstable country taken over by militant Islam, many twitter users included the hashtag #undercontrolofmilitantislam in their tweets, to protest and mock the president’s comments (see image 2).

Image 1: Kosovo ambassador to the US tweet, May 30, 2019

Image 2: Emir Suljagić tweet, July 31, 2019

Approaching the internet as a cultural space in which meaningful human interactions occur (Markham 2018: 657) allows us to connect the study of hashtag activism and hashtag memory activism to discussions of frameworks such as digitally mediated connective action (Bennett and Segerberg, 2012) and mediated mobilisation (Lievrouw, 2011).

Memory activism has been the focus of my research for more than a decade now, and in my recent work I explore and discuss the noticeable turn towards online platforms for purposes of online commemoration and advocacy, and the growing use of hashtags by memory activists in their memory work. In light of the ‘connective turn’ (Hoskins, 2018), the field of memory studies is undergoing developments and changes. According to Hoskins, “digital technologies and media have transformed remembering and forgetting”. Here I aim to shed light on the ways these technologies and changes have also nuanced, enriched, or otherwise affected mnemonic practices and the ways memory activists use hashtags in their memory work, which I refer to as Hashtag Memory Activism.

The use of hashtags has become prominent in the growing phenomena of online commemoration and online memory activism. In my current research on memory politics and memory activism in Serbia, as related to the memories of the 1990s, I have observed an increase in the use of hashtags on social media platforms by local memory activists addressing the contested pasts in the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, as well as the appearance of online commemorations. These online activities almost always supplement rather than replace onsite activism and onsite commemorations.

Employed as a strategy of peace activism, memory activism is discussed here as activism oriented towards the past, a knowledge-based project promoting consciousness-raising and political change, undertaken outside the channels of the state (Gutman, 2017). Memory activism can appear in times of an ongoing conflict, as well as in its aftermath. As I show in my discussion below, through cases of both post-conflict dynamics of memory politics (as in the case of Serbia and the post-Yugoslav successor states) and ongoing conflict (as in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict), memory activists utilize hashtags to engage with forbidden ideas and commemorations, with disputed or silenced memories and terminologies, and with topics from concealed pasts. I define hashtag memory activism as the online commemoration of a contested past on social media, which entails the use of hashtags as a mnemonic practice; Hashtag memory activism can be employed as a mnemonic tactic which enables the creation of alternative platforms for remembrance, with the aim of sharing and disseminating alternative knowledge about a contested past among societies in and after conflict (Fridman, 2019). The hashtag as a mnemonic practice is thus being appropriated by activists as part of their memory work and advocacy campaigns. The choice of the hashtag’s language is interesting as well. It may indicate the target population for the action itself, as well as the identities of those who initiate hashtag memory activism campaigns, and those who participate in them.

In what follows I introduce the analysis of two of a number of hashtags I am currently studying. The first is related to mnemonic battles in the post-Yugoslav space: #NisuNašiHeroji (#NotOurHeroes); the second is the #MyNakbaStory hashtag, related to the memory of 1948 in the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Among various questions, I explore the genealogies of each hashtag, its initiators and users, its significance to the study of online commemorations and local or regional dynamics of memory politics.

#NisuNašiHeroji (#NotOurHeroes): Generational Mnemonic Claims, Online Memory Activism, and the Post-Yugoslav space as a Region of Memory

With the closure of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in late 2017, across the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, ICTY convicts who completed their sentences (or following early release) began to return home, where they were and still are often received as heroes. In Serbia, as well as in Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Kosovo, prominent convicts reclaimed roles in public life. This was when the young generation of memory activists from Serbia began to engage with these returning convicts, attempting to obstruct their public appearances and protesting at their rehabilitation and return to public life (Fridman, 2018). Among other actions, they began using a hashtag to accompany with their social media appearance and memory activism: #NisuNašiHeroji (#NotOurHeroes). The activists, members of the Youth Initiative for Human Rights (YIHR), used the hashtag as they positioned themselves through the choice of the word Our/Naši, to indicate their belonging to a specific generation. As a regional NGO that was first formed in Belgrade (Serbia) in 2004 and today has offices in Prishtina (Kosovo), Zagreb (Croatia), Sarajevo (Bosnia-Hercegovina) and Podgorica (Montenegro), they make a generational claim, as they form a region of memory of the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, in relation to the contested memories of the wars of the 1990s throughout the region. They argue they are ‘too young to remember but determined never to forget’ and that these ICTY convicts are not the heroes of their generation.

On December 10, 2017, which marked International Human Rights Day, as the ICTY was closing its doors following the verdict in the Ratko Mladić trial, the group posted a composition of five pictures of their activists standing in well-known public locations in the capitals of five Yugoslav successor states, where they engage in local and regional mnemonic struggles, holding banners with their hashtag #NisuNašiHeroji [in Kosovo translating the hashtag into Albanian]. The post read: “In 2018, the [youth] Initiative will continue to fight for a society where war crimes perpetrators are not role models, and denial is not considered top-level patriotism. On this Human Rights Day, once again from the entire region, we say [war] criminals are #NotOurHeroes” (Image 3).

In utilising hashtag memory activism, these activists are making their generational claims visible and more public. Additionally, they claim theirs is not only a national struggle but a regional one, by using the same message and the same hashtag, in both their online and their onsite actions, throughout the region. As such, their campaign included demonstrating against actions such as the erection of a monument honouring the late Franjo Tudjman in Zagreb,[1] and calling on heads of state and government officials to refrain from including convicted war criminals in public positions.[2]

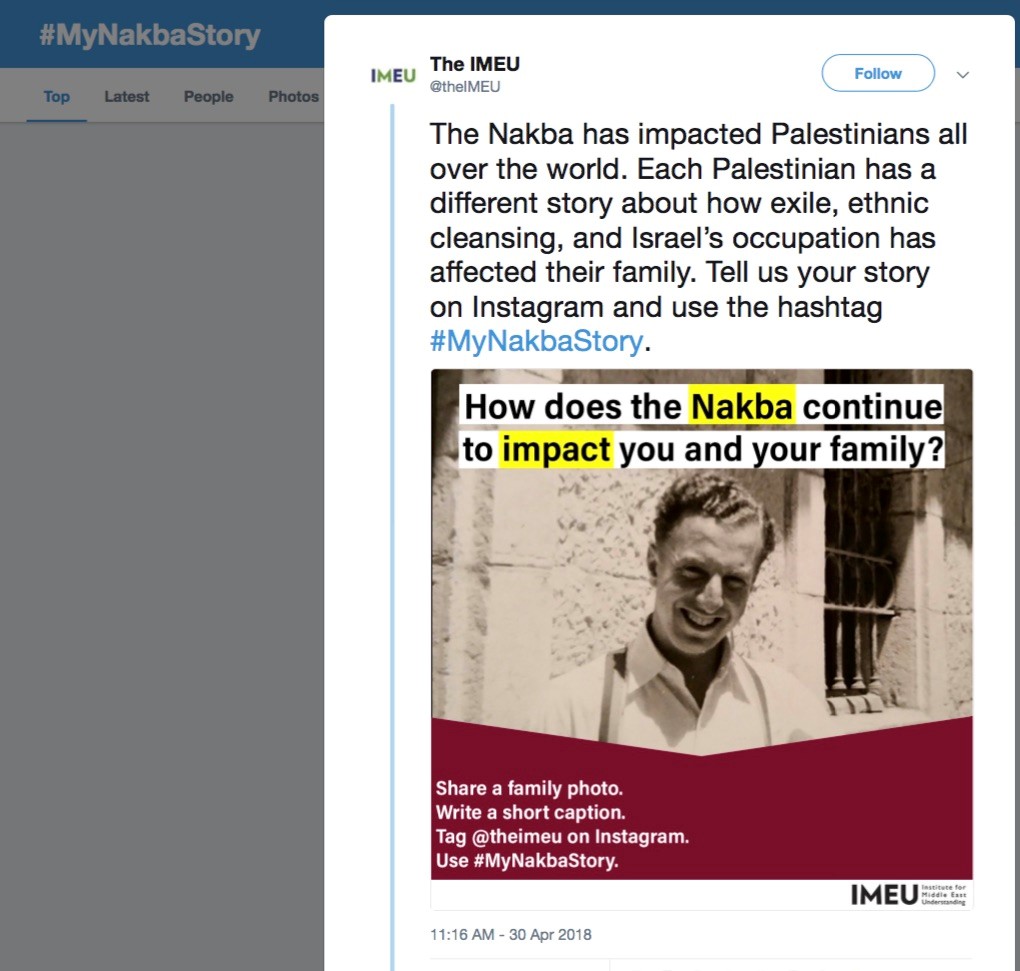

#MyNakbaStory: Hashtag Memory Activism and Online Commemorations as an Advocacy Tool

The #MyNakbaStory hashtag appeared prior to the May 2018 commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the 1948 Palestinian Nakba. In Israel/Palestine (on-site), in the weeks building up to the 2018 commemoration of Nakba Day, the situation on the ground escalated with the move of the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and the large-scale demonstrations at the Gaza border (referred to in Arabic as the great March of Return), which resulted in the shooting of a large number of victims by the Israeli military. At the same time, responses began to appear online to an invitation from the US-based Institute for Middle East Understanding (IMEU) calling individuals to share their personal family Nakba stories and use the hashtag #MyNakbaStory (Image 4).

The Nakba, perceived by Palestinians as an ongoing event from 1948 through the present (Abu-Lughod and Sa’di, 2007), was thus given an online platform, used mainly by diaspora Palestinians based in the United States, who shared their family stories of loss, migration, and refuged, denied by the state of Israel and by Jewish Israeli society in its memory regime and memory laws.

“The Nakba was not only the past,” as one prominent activist for Palestinian rights explained to me, “but is still an ongoing phenomenon and is part of an ongoing process… it may have been in its infancy in 1948, but has continued in a number of ways on a singular historical trajectory since then” (Interview with the author, Skype, May 7, 2019). Nakba is about the present, as the various commemorations of Nakba Day emphasise each year. Nakba Day is now firmly established in the Palestinian calendar, among Palestinian citizens of Israel (joined in smaller numbers by Jewish Israeli activists), as well as in the West Bank and Gaza (Sorek, 2015), and around the world. Just like on-site commemorations, online commemorations of Nakba on May 15 have grown and evolved in recent years.

In 2018, the initiators of the campaign at the IMEU decided to add the word ‘my’ to the previously used hashtag #NakbaStories. For them, this was a way for Palestinians to push back against what they see as ongoing attempts to erase their culture and history.[3] As such, on digital social platforms, people are able to share their family stories and narratives without restrictions, physical borders, walls or checkpoints. By doing so, it allowed them to place Palestinian heritage, the memories of expulsion and the narratives of the refugees themselves, at the center of the story, and of the commemoration of the Nakba 70 years later.

Situating these narratives and images of the Palestinian presence and culture from the early 20th century in Palestine, participants assert not only a cultural belonging but also their political mnemonic claims. As Yousef Munayyer, a US-based Palestinian rights advocacy activist [4] put it:

“there is a tremendous amount of ignorance and misinformation and even myths about Palestinians in general, and Arabs and Muslims more broadly… as being uncivilised cave-dwellers who only came to existence once Israel did… when I posted my thread, I placed a picture of my family, of my grandparents wedding day in the 1920s… in the popular imagination, such images of Palestinian civilisation comes as a surprise to so many people… an image that does not fit the limited stereotype of Palestinians as terrorists….” (Interview with the author, Skype, May 7, 2019) (see Image 5).

The choice to use the hashtag only in English and not in Arabic reflects efforts to target the campaign at a Western audience and more broadly to help people better understand the Palestinian struggle, allowing diaspora Palestinians, mostly from North America, to connect and act together in the digital sphere.

****

These very short excerpts from my current research on Hashtag Memory Activism highlight the importance and innovation of this framework of analysis in the study of memory politics. This framework can be used for the examination of mnemonic struggles both in and after conflict and helps to retrieve a rich body of empirical data through social network analysis methods. Each hashtag has its own genealogy, political and mnemonic context, and various creative uses as a mnemonic practice. Each one thus reflects processes of participation and articulation as well as dynamics of change, and highlights the importance of the study of memory activism and online commemorations and its contribution to critical peace and conflict studies.

Footnotes

[1] In a counter-demonstration in Zagreb against the erection of the Tudjman monument on the 19th anniversary of his death on December 10, 2018, activists of the Zagreb YIHR office (joined by a number of other groups from Croatia) held up a sign with the hashtag #NisuNašiHeroji. See http://hr.n1info.com/Vijesti/a354523/U-Zagrebu-prosvjed-protiv-postavljanja-kipa-FranjiTudjmanu.html?fbclid=IwAR1jcCsrejc2KE1YzU8ZzG1mI1ylJTgzRhAm2LVTFFWDzOpuklW6kp2B0MA and https://balkaninsight.com/2018/12/10/the-greatest-monument-of-former-croatian-president-unveiled-in-zagreb-12-10-2018/ (accessed on June 10, 2019).

[2] See the YIHR Kosovo and Serbia joint statement http://www.yihr.rs/bhs/ratnim-zlocincima-nije-mesto-u-vladi-kosova/, where they condemn and protest the appointment of Sylejman Selimi as an advisor to the Prime Minister of Kosovo, Ramush Haradinaj. In July 2019, Haradinaj resigned from office on being summoned to the Special Tribunal in The Hague for questioning.

[3] This corresponds to other campaigns on social media. See for example the #TweetYourThobe campaign that was launched on January 3, 2019, to celebrate Palestinian culture and the induction of Rashida Tlaib to Congress. Susan Muaddi Darraj, https://972mag.com/palestinian-sumud-tatreez/141238/; As Rashida Tlaib Is Sworn In, Palestinian-Americans Respond With #TweetYourThobe January 3, 2019 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/03/us/politics/rashida-tlaib-palestinian-thobe.html; NPR January 6, 2019 https://www.npr.org/2019/01/06/682607997/viral-hashtag-celebrates-palestinian-american-representation.

[4] Munayyer and others with whom I spoke define themselves not as memory activists but rather as advocacy activists for Palestinian rights. For them, at the present, remembering and reminding people about 1948 are part of a broader struggle for justice and rights. Here I refer only to their online activism and use of the #mynakbastory hashtag as memory activism.

Bibliography

Abu-Lughod, Laila and Ahmad H. Sa’di (2007). “Introduction: the Claim of Memory,” in Laila Abu-Lughod and Ahmad H. Sa’di (eds.) Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory, Columbia University Press.

Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg (2012). “The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics.” Information, Communication & Society. Vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 739–68.

Bonilla, Yarimar, and Jonathan Rosa, (2015). “#Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States.” American Ethnologist. Vol 42, 4-16.

Fridman, Orli (2015). “Alternative calendars and memory work in Serbia: Anti-war activism after Milošević.” Memory Studies, Vol. 8, 212–226.

Fridman, Orli (2018). “Too Young to Remember Determined Not to Forget”: Memory Activists Engaging with Returning ICTY Convicts.” International Criminal Justice Review, Vol 28 no. 4, 423–437.

Gutman, Yifat (2017). Memory Activism: Reimagining the Past for the Future in Israel-Palestine. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Hoskins, Andrew (2018a). “The restless past: an introduction to digital memory and media,” in Andrew Hoskins (ed) Digital Memory Studies: Media Pasts in Transition. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Hoskins, Andrew (2018b). “Memory of the multitude: the end of collective memory,” in Andrew Hoskins (ed) Digital Memory Studies: Media Pasts in Transition. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Lievrouw, Leah A (2011). Alternative and Activist New Media. Digital Media and Society Series. Cambridge: Polity.

Markham, Anette N (2018). “Ethnography in the Digital Internet Era: From Fields to Flows, Descriptions to Interventions,” in Norman Denzin and Yvonna Lincoln (eds.). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: Sage. 650-668.

Sorek, Tamir (2015) Palestinian Commemoration in Israel: Calendars, Monuments & Martyrs. Stanford University Press.

Yang, Guobin (2016). “Narrative Agency in Hashtag Activism: The Case of #BlackLivesMatter.” Media and Communication. Vol. 4, No. 4, 13-17.