Nuraini Juliastuti and Carine Zaayman

AHIR – University of Amsterdam and Free University of Amsterdam

On 3 August 2021, we visited the Museum Volkenkunde, one of the museums that forms part of the Dutch National Museum of World Culture, to see the exhibition “First Americans: Honouring Indigenous Resilience and Creativity”. Both of us come from places that were colonised by the Dutch – Nuraini from Indonesia, and Carine from South Africa – and from whence objects have been collected and put on display in this museum. Like many travellers before us, we were curious to see not an exhibition about a “somewhere else”, but rather how this museum would represent the worlds that we ourselves come from.

Breaching Frames

Carine Zaayman

Walking into the museum on our visit, I thought of how these doors function more as frames than as portals. We already know that museums – especially ethnographic museums – frame the objects they display, petrifying them in a museological gaze. Objects are isolated in vitrines, illuminated with soft spotlights. Information on the objects are conveyed via authoritative labels. Any encounter with objects within a museum is carefully staged. But what of the outside world, where the impermanence of everyday life renders the world changeable and transient, where unanticipated meetings, connections, conflicts and friendships emerge continuously?

Museums frame not only the objects inside its galleries, but the world outside. As everything in the museum works in concert to confer value on the objects on display, it simultaneously implies that the world lying beyond its walls, outside the frame constituted by the building itself, is lacking in this value, and does not necessitate the same careful consciousness of encounter. What is more, the way in which the museum lays claim to authenticity through authoritative, didactic gestures, suggests that worlds past and far away find their truest representation within it, rather than on the street. Framing, as manifested in the museum, does not begin or end at its doors. Rather, these doors demarcate an “inside” and an “outside”, thereby contributing to the making and unmaking of worlds within the world.

Yet we also need to remember that displays in any museum do not all necessarily conform to the same logics: As new personnel are appointed and discourses develop that in turn engender practices that imagine the functions and ethics of the museum anew, institutions do change. The Museum Volkenkunde for instance, carries within itself traces of such developments. The exhibition “First Americans: Honouring Indigenous Resilience and Creativity” surfaces various ways in which the world outside the museum is in flux, and hence adopts a more hybrid language of display, one that traces more consciously those connections between objects one might encounter elsewhere in the museum and their contemporary utilizations in the world. Artworks by Cara Romero, for example, references conventional museological arrangements of objects by photographing them as though they existed in a recess. While the containment of the objects in a box-like structure recalls the way in which museum displays conventionally arrange objects explicitly for the purpose of visual consumption, Romero situates the “vitrine” as object as part of the display by focusing attention to the box itself, covering it with bold colouration and striking pattern. She further includes an image of herself, wearing an extensively beaded dress crafted by five female members of her family over the period of a year. By including her own body, facing front, she invokes the conventions of museum objects and photographs of people meant to serve as “types”. However, as the author of the image, she claims ownership of her self-imaging, as well well as the objects she wields.

The authors

American Families | The authors

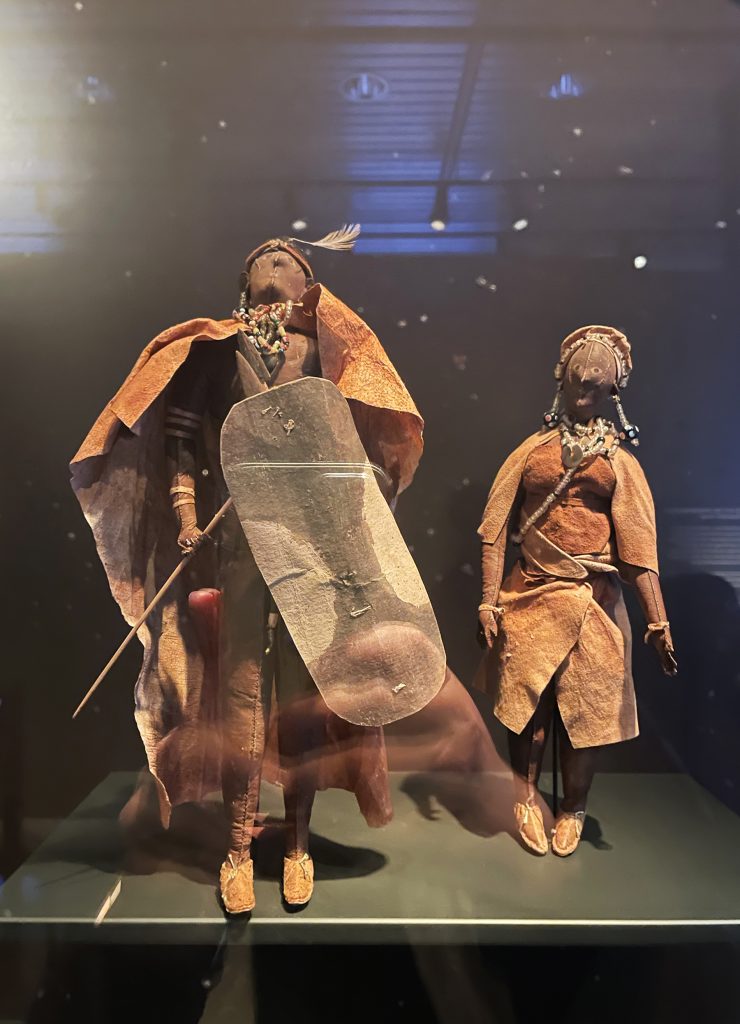

I had Romero’s work in mind when, after we had visited the “First Americans” installation, we made our way to the permanent display of objects from Southern Africa. Here I had a different relationship with the installation we encountered, because it instantiates a conception of the place where I come from. Scholarship, activism and artistic interventions have offered a host of critique against the authority that museums claim, troubling the power exercised by the museum over the way in which the world is conceived, but importantly, these critiques are often founded on the experiences of those who are bodily, intellectually and emotionally invested in the worlds that the museum represents. I deeply felt my own investments as I looked at the various diminutive figures dated from around 1820-1883, sometimes referred to as “dolls”, pressed into service to represent various “ethnic” groups from the Southern African region. The label for the “Zulu or Xhosa man”, for example, informs us that the “clothing, jewellery and attributes are depicted with great accuracy”, and therefore “the doll-maker must have had a great deal of contact with the indigenous population.” Unlike Romero’s photographs, these figures are decidedly not ones of self-representation, nor is any acknowledgement made of how the identities of groups of people in Southern Africa have always been in flux and thus, there can be no “types”. No attention is paid to the agency and creativity of the peoples (ineptly) represented by these figures. The petrifying gaze of the museum operates on these figures in many ways, not least by reducing them to the scale of toys, pairing male and female figures into couples, and rendering them inactive, docile.

These diminishing modes of presentation are not without implication for the world outside the walls of the museum. Rather than engendering an understanding of the places whose objects they display, museums often make it harder for European audiences to find connection with people from all over the world, exactly because of its tendency to typify rather than acknowledge flux, thus erecting a mirage of authority and knowledge that serve as foundation for European imaginaries of “elsewhere”. In the Museum Volkenkunde, the display pertaining to Southern Africa is a reminder of both the extent and the ease with which the museum frames the world outside its boundaries in the minds of its visitors. “First Americans” offers a more promising approach, in that artists and activists jettison notions of authenticity founded in colonial epistemology in favour of contemporary voices. Moreover, it draws the museum and its conventions into the frame of the exhibition itself. It would serve the museum to utilise such strategies of re-framing across all its halls.

Making our own stories in a museum

Nuraini Juliastuti

I have visited the Indonesian permanent collection in the Museum Volkenkunde many times. On each visit, I always have this feeling, a mixture of being in a place and surrounded by familiar stuff, the willingness to excavate something extra, something more special, and being blasé at the same time. Oftentimes this blasé feeling takes center stage and creates uncomfortableness. It makes me wonder about its source and why I feel like this. In everyday conversation, there is a popular saying of dimuseumkan, or ‘to be museum-ized’, an Indonesian expression, if critical, to say to put something in a particular place and let it be abandoned. My theory is that my blasé-ness is informed by this kind of expression.

Museums, along with census, and map, to follow Benedict Anderson in Imagined Communities, are three important tools for colonisation. Anderson writes, “they profoundly shaped the way in which the colonial state imagined its dominion — the nature of the human beings it ruled, the geography of its domain, and the legitimacy of its ancestry.” The politics of museumized in the colonial eras followed the logic of salvage. The colonial objects were excavated, unearthed, mapped, being cared for and protected in the name of scientific rationalisation. Anderson observed that the politics of museumizing in post-colonial states often followed the logic of the colonial’s way of conservation. The post-colonial museums emerged as new sites for the construction of national identity through demonstrating the official display of what Anderson referred to as the ‘evidence of inheritance.’

Various objects in the museums are arranged systematically in carefully curated manners. Their stories have been gleaned. They become contained objects labelled with tags giving brief information to describe the names, ages, and functions. Anderson refers to the museum as rumah kaca, a glass house, coined by Pramoedya Ananta Toer. A glass house, Pramoedya wrote in the latest book of his Buru Quartet tetralogy, House of Glass, represents a condition of total control. Anderson said that it is a ‘total surveyability.’ In a museum, which also functions like a glass house, the meaning and the stories are confined within the limitations of the frames, the vitrines, and the labels.

There is something in those limitations which prompted me to associate a museum visit with the act of memorising dates, names of people, objects, places, and moments, with history classes during the New Order (1966-98). I was born and grew up under the New Order regime and, whether I like it or not, it has informed my perspective on history. The history textbooks embodied the rigid official frameworks which dictated which narratives the public should learn (and memorise). The official histories tend to suppress other stories. Part of my experience of being a teenager during the 1990s was to unlearn these history textbooks, hijack them, and find other sources of histories. Many others who experienced both the New Order and the reformasi movement, are compelled by the desire to look for alternative histories; other voices, which are able to reveal everything that has been concealed or repressed. What we usually see in museums and other state-based institutions in Indonesia rarely represents what we want to see. Perhaps my indifference when visiting the ethnology museums stemmed not from a lack of interest, but from such a desperation to get a sense of connectedness and relevance.

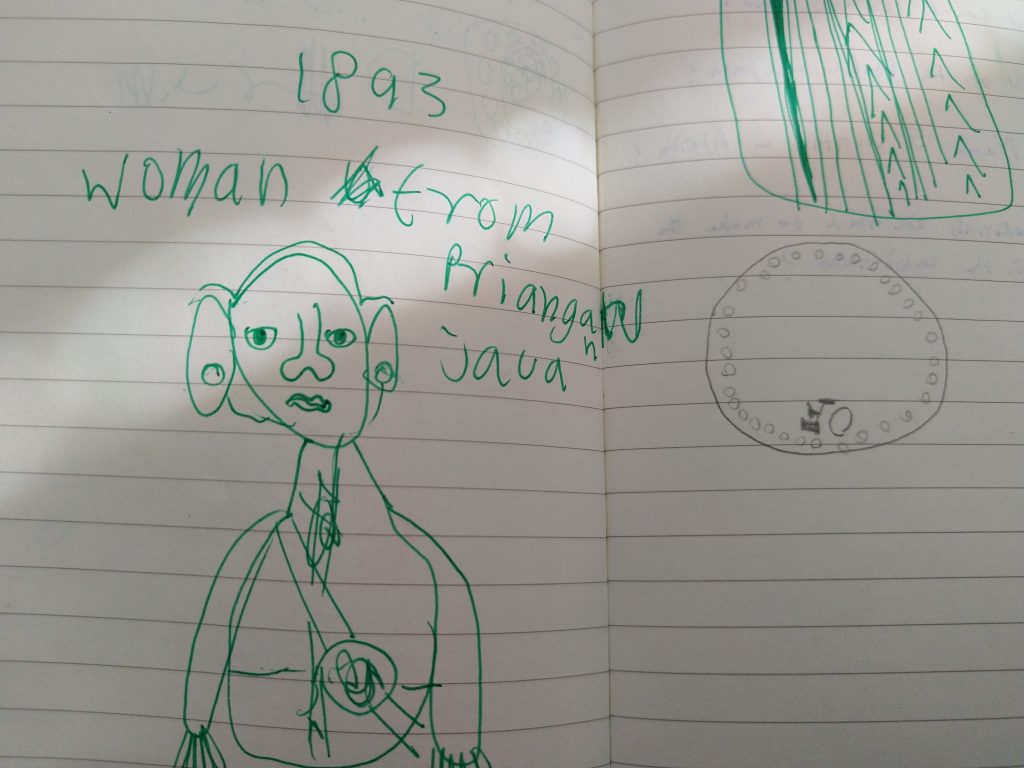

In June (2021), after lockdown restrictions were lifted, I visited the Volkenkunde again with my partner Andy and daughter Cahaya. We were in the Indonesian permanent collection room, and Cahaya started to get restless. Andy came up with an idea of a museum activity. He wrote five questions. The questions were the following: 1) Find five different objects from different islands of Indonesia; 2) What is the oldest object you can find?; 3) Tell us about your favorite object?; 4) Can you find some jewelry? Can you find any weapons? (Like a sword or dagger?) Can you find any musical instruments?; 5) Can you draw the batik patterns? Can you draw a figurine? He wanted to apply some kind of rudimentary game-like experience to being in the museum.

In order to answer the questions, Cahaya needed to walk around the room, looking at the objects displayed inside the vitrines. Her immediate response to the questions was “This is like a treasure hunt game, but our own style.” The museum provides treasure hunt games packages for children visitors. The instructions, however, are only in Dutch. Cahaya’s Dutch proficiency was not yet sufficient to understand them. So she could not play the game fully. But then I saw Cahaya was engaged in the questions that Andy posed, looked at the objects, wrote, and sometimes drew the answers in her red notebook.

Fred Moten, reflecting on his collaborative writing process with Stefano Harney in their book, Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, referred to the process using the pretend game that his children always played all the time as a metaphor. The essence of the play, as Moten observed, is interaction. In the pretend game, his children created their own world. As they created this world, they invited the participation of other people. Their game emerged as a way for creating different kinds of relations. A collaboration requires a condition where everyone can see their relational position and think what they can do about it.

As I looked at Cahaya’s drawings, which were based on the objects she saw in the Indonesian permanent collection room, I realised that this might be a way of breaking the structural limitations of a museum. And the way to do it can be realised through turning the museum into an arena for play. Cahaya’s treasure hunt game opened up new possibilities to interact and communicate with the museums in a different manner. The museum can be a space where I can think about what is closest to my environment.

This is the thinking that I brought to mind when I walked into the “First Americans: Honouring Indigenous Resilience and Creativity.” This exhibition is part of the contribution that Volkenkunde made to the Leiden 400 Years event. The year 2020 marked the 400 years since the Mayflower, the ship carrying refugees from religious persecution and adventurers from England arrived in America. The pilgrims had lived in Leiden before they continued their journey to North America. The museum objects contain the stories of traveling, under the frameworks of conquest and colonisation. In Museums as Contact Zones (1997), James Clifford encourages us to see the museum objects as travellers or crossers. But there is a different ambience emanating from the First Americans exhibition room. First Americans turned the traveling narratives around, and through narrating the indigenous resilience and creativity, it shows that the destination of the pilgrims is not terra nullius. The indigenous communities were and will always be there, and they are never ceded.

In There is Hope, If We Rise (2014) Sonny Assu created a series of posters containing images and words like “resist, confront, lead, learn, idle no more, never idle, decolonise, rise.” Next to the poster series, there was a banner with a woman carrying a water container. The woman was portrayed with a heart symbol in her chest. There was a baby in her womb. She screamed, that was how it seemed to me, “Water: Agua Es Vida.” I continued walking through the small room displaying various posters, photographs, artefacts, drawings, and documentations of the indigenous movement. I stopped in front of a red square banner with the symbol, a red painted hand across the face, scattered in the centre of the banner. The symbol represents the ongoing campaign of the Missing and Murdered Indigeneous Women (MMIW). The initiative has been working to increase awareness of the high rates of violence towards indigenous women in Canada and the United States.

Virgil Ortiz shows a photograph of a black and white corn clay pot embellished with floral and geometrical patterns in Corn Pot in the Indigenous American Families (2005). The corn pot narrates the stories of resistance through food. The photograph reminds me of the people across various communities in Indonesia who carve their independence through ‘foodways’. In their own ways, these people attempt to navigate the difficult paths to make a more direct and meaningful link between food consumption, a sense of dignity, and market forces in everyday life. The market provides almost everything, but this often leads to the consumption which only makes us move away from our lands. The corn pot symbolises the reconnection with food which also shows a strong life perspective.

I saw everything in this room as a display of allies, brothers and sisters who are standing together because they share their ongoing struggles. When a museum opens up itself as a space for struggles, the rooms become zones for solidarity. This is the concrete phase of becoming a caring space. The exhibition serves as an avenue through which I can make connections with that which is beyond the museum gate.

Pathways Home

As we said goodbye to one another, we each made our way to our new homes in the Netherlands. Nuning left the museum and walked down Steenstraat. On both sides of the street are the small eateries selling food from Syria, Turkey, Suriname, Indonesia, Vietnam — old and new migrants. At the end of the street is the Mayflower Hotel, named after the ship that brought the pilgrims on their journey to America 400 years ago. She thought about the indigenous communities who welcomed the pilgrims to America and how their lands, cultures, and people disappeared systematically. She looked at the eateries on the Steenstraat and thought about how these migrant communities made their way to the Netherlands, and made attempts to revive the memories of their lands. Carine made her way to the station, thinking of how the trains connect various suburbs and streets across the Netherlands named for former (and some current) Dutch colonies: Transvaalbuurt, Makassarbuurt, Lombok, and so on. She wondered about the conceptual and material impact of how museums conduct their work on life in these places, as well as the places for which they were named. Nuraini and Carine might have come from elsewhere, but we forged a friendship because our paths have intersected in the museum. Each of us carries a number of worlds with us, worlds replete with complexity, struggle and joy. We are working to build connections between these worlds and many more besides. It is our hope that in our work, the museum can become an ally.