Richard J. Evans

Regius Professor Emeritus of History

University of Cambridge

There are plenty of movies about the Holocaust, but it’s rare to have one about Holocaust denial. One such film, however, was Denial, released in 2016 and directed by Mick Jackson, best known for Volcano and Bodyguard, both made in the 1990s. It starred the well-known British actors Rachel Weisz, Timothy Spall and Tom Wilkinson, and it focused on the civil action for libel brought before the High Court in London in the year 2000 by the writer David Irving against the American academic Deborah Lipstadt over the allegation she made against him in her book Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, published in the UK in 1994. Lipstadt had called Irving a Holocaust denier and a falsifier of historical evidence. Irving issued a writ for defamation, claiming this damaged his reputation and thus affected his livelihood as a freelance historian.

Over three months, from 11 January to 11 April 2000, the case was fought out between Irving, who represented himself, and the senior barrister Richard Rampton QC, instructed by the solicitor Anthony Julius, who had previously won fame as Princess Diana’s lawyer in her divorce from the Prince of Wales. The parties had agreed that the trial should be held before a judge alone, since the issues were too complex for a jury to grasp. Lipstadt’s defence relied on what is called ‘justification’, that is, her book was indeed defamatory but everything it said about Irving was true, an absolute defence against a libel suit in English law.

The defence relied mainly on expert witnesses, of whom I was one. My task was to go through Irving’s work with a view to seeing whether Lipstadt’s allegations were justified. As well as obtaining copies of his numerous books in English and German, the defence also obtained a court order obliging Irving to ‘discover’, or in other words make available, audio and video recordings of his numerous speeches, his correspondence with publishers, his research notes and much more besides. To cope with this enormous mass of material, I used the services of two of my research students, who were paid at an hourly rate by the defence, as indeed I was myself. Preparation for the trial began in 1997, and with the aid of a sabbatical as I moved from my professorship in London to a new post in Cambridge, and with the help of my researchers, I completed an independent 740-page report in July 1999. In it, I found Lipstadt’s charges against Irving fully justified; I was cross-examined for 28 hours by Irving in court, and successfully defended my report throughout.

The judge ruled against Irving and Lipstadt was vindicated. Irving had bent the evidence to fit his prejudices, manipulating and falsifying historical material to support his Holocaust denial, that is, his belief that only a small number of Jews were killed in World War II, not six million, the commonly accepted figure; that there was no plan or programme to kill them, they were just casualties of war; that Hitler did not know about the Holocaust, or alternatively, if he did know, he tried to stop it; that gas chambers were not used to murder Jews; and that the evidence for the Holocaust was invented by Jews after the war. Costs were awarded against Irving, though he then declared himself bankrupt so did not have to pay them. Irving asked for leave to appeal, but in a separate hearing before three judges his request was denied.

Media interest in the case was intense, though mostly it focused on the verdict. While the trial was in progress, most newspapers found the proceedings too tedious and too complicated to follow, not least because they involved extensive documentation in German, and editors were anxious not to say too much in case Irving won. With the verdict in their hand – a detailed 350-page ruling on the case by the judge – they could go to town and call Irving a liar and a cheat. The massive press and media coverage provided an extensive lesson for the public in the history of the Holocaust and the dishonesty of those who denied it. Although the trial was about what Irving had written in his study and said on his speaking tours and not what happened at Auschwitz and elsewhere during the war, the implications were unavoidable. It was a crushing defeat for Holocaust denial.

Small wonder, then, that television directors and filmmakers began to think about how to put it onto the screen. The first attempt, Holocaust on Trial, was made for PBS in America while the trial was in progress, using dramatizations of the daily trial transcripts, archive footage, and ‘talking heads’, i.e. historians of the Holocaust, such as Richard Overy and David Cesarani. It was very much instant history, made without a great deal of reflection. A second television film, History on Trial, made for BBC-2, was more successful, though it followed very much the same formula. Some care was taken to ensure the actors roughly resembled the reallife people they played. I was phoned up by the production team in advance, for example, and asked about my height and weight, my age and the colour of my hair). I was played by the British actor Michael Kitchen, whom I encountered by chance in a London café a few months later (‘I hope I played you to your satisfaction’, he said: ‘You played me far better than I played myself’, I replied: ‘You could rehearse the lines, while I only had one go at delivering them when I was in the witness box’).

The documentary style, however, would not do for a commercial movie to be shown in cinemas. This had to be a full-scale dramatization, and this is where the trouble began. It is notoriously difficult to make a courtroom drama work, particularly after the success of 1954’s Twelve Angry Men – and the Irving-Lipstadt trial hadn’t even had a jury to enliven the proceedings. An attempt was made by Sir Ridley Scott, a leading Hollywood director, with huge successes such as the Alien franchise to his name. Scott engaged Sir Ronald Harwood, an experienced playwright and screenwriter to produce a screenplay. Harwood had won an Oscar in 2003 for The Pianist, a Holocaust drama, and seemed the right man for the job. But the screenplay he produced was still too much of a courtroom drama for Scott, who passed it over to Nicholas Meyer, a Hollywood ‘script doctor’, novelist and film director, to see if it could be improved. It seems that it could not, at least not to Scott’s satisfaction, so it joined the long list of

unrealized projects gathering dust on the shelves of Hollywood’s movie producers.

The problem was that a movie needs a character or characters for the audience to identify with, and there just wasn’t one. It was only when Deborah Lipstadt published her own, very personal account of the trial in 2005 that one became available: the defendant herself. The case was picked up by Sir David Hare, an experienced playwright, film and theatre director and twice-Oscar-nominated screenwriter. Hare had long been interested in the Nazi period and the Holocaust, and he began adapting Lipstadt’s memoir History on Trial: My Day in Court with David Irving, for the screen. As part of the preparation, he interviewed most of the major players, including myself. In a two-hour interview in my Cambridge office, accompanied by a note-taker, he went over the case with me, always looking for an interesting angle and colourful details. As he left my office, he turned to me and remarked: ‘Everyone I’ve talked to sees the case differently’. This led me to believe he was considering an approach to Kurosawa’s classic film Rashomon, where each character has a radically different memory of a crime they have witnessed or participated in.

Given his many other commitments, it is not surprising that it took Hare several years to complete the project, generate the funds needed to carry it through, get a movie company to take it on, and find a distributor. More time was inevitably taken up by the casting process, location identification, set construction and all the other business generated by a major commercial movie. Filming began in 2015, and in 2016 Denial was completed and presented to the public. As it turned out, it wasn’t a reworking of Rashomon at all, but a relatively straightforward chronological account. The movie received respectful reviews; box office receipts narrowly failed to cover the costs of making it. For someone who was involved in the action almost from the start, and who attended the great majority of the 35 days that the case was heard before the High Court in London, the interesting question was how accurate the movie was in its portrayal of the character, the action and the issues at stake.

Filmmakers inevitably have to make compromises with the truth when turning an historical event into a drama: that is why the phrase ‘based on a true story’ occurs so often in the credits of movies that follow historical reality. Actual history is messy, complicated, full of confusing twists and turns, and often not very interesting: a movie has to smooth it all out, reduce the plethora of characters to a manageable number, and make sure the audience understands them from the outset issues and grasps the nature of the issues at stake. Equally, however, it is important, particularly when dealing with such a sensitive subject as Holocaust denial, that the filmmakers do not depart too radically from what actually happened in the effort to inject an element of drama into the proceedings and keep the audience interested.

The first of these compromises happens in the movie when Irving turns up at a lecture delivered by Lipstadt in her home university in Atlanta, Georgia, and stands up in the audience to deny the Holocaust and offer a large sum of money to anyone who can prove to his satisfaction that it actually happened. Irving actually did make this offer, but not to Lipstadt, not in Atlanta and not in the 1990s but some time before. Still, the offer, which was of course merely rhetorical because there was no way he was ever going to admit its conditions had been met, plays a useful, perhaps essential role in the movie by introducing Irving as a character and showing the audience what he was like and what he believed.

Irving is played by Timothy Spall, who is about as physically unlike Irving as you can get: he is short, whereas Irving is tall; he played Irving as weaselly and insinuating, whereas the real Irving is loud, bulky and overbearing. The casting directors indeed did not make much of an attempt to have the actors resemble the real-life people they were playing, though they did give Rachel Weisz a red wig to match the colour of Deborah Lipstadt’s hair, and she also painstakingly learned to speak with Lipstadt’s accent, which originated in the Queen’s borough of New York. Spall made up for in thespian energy what he lacked in physical stature.

Similarly, Tom Wilkinson is taller and bulkier than Richard Rampton, the defence barrister, but went some way towards capturing his scholarly demeanour and his rhetorical clarity. The scene in the movie where Rampton goes to see Deborah Lipstadt in her London hotel room is entirely invented, but is part of the movie’s (largely successful) effort to give the characters a more human dimension than would be possible if the film had been largely confined to the courtroom. Rampton was indeed genuinely moved in many different ways by the case, in particular by the contrast between the appalling sufferings of the Holocaust victims, and the callous appearance presented by Irving’s denialism.

Movies can’t afford to have too many characters or it becomes impossible in a two-hour or slightly over two-hour performance to give depth to any of them, so the other expert witnesses, testifying to the actual evidence for the Holocaust that Irving was alleged to have falsified, and to Irving’s ties to extreme right-wing politics, were cut out of the picture. On the other hand, there were some new characters too, including a friend of Lipstadt’s in whom she confides her feelings about the action, and a Holocaust survivor, Vera Reich, played by Harriet Walter, inventions that serve to dramatise the issues in a directly human way.

There were in fact quite a few Holocaust survivors in the courtroom’s public gallery, who had turned up their shirtsleeves to reveal the Auschwitz tattoo numbers on their forearms; the character of Vera Reich is a way of pointing up the fact that the defence decided early on not to call any survivors into the witness box even though some, represented by Vera, did indeed demand to be heard. Subjecting elderly people to a man, Irving, who claimed not to believe their experiences were real, and who would pounce, as he had done on other occasions, on the slightest lapse of memory to try and discredit them, would not have been ethical; but more importantly, the trial, unlike the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem decades before, which had relied heavily on survivor testimony, was not, as already noted, about whether the Holocaust had happened, but about whether Irving was a right-wing extremist who falsified the historical record of the Holocaust, and hearing survivor testimony would have taken attention away from this central focus on the claimant, undermining the defence case in the process.

Denial is very good at explaining clearly and convincingly both the peculiarities of English libel law, where in effect the defendant has to prove innocence rather than the claimant having to prove the defendant’s guilt, which would seem on the face of it to be more just, and the thrust of the defence’s strategy, which demanded that Lipstadt herself remain silent throughout the trial, despite the fact that she was desperate to speak in her own defence. As her solicitor Anthony Julius explains, putting her in the witness box would have taken the heat off Irving; turning the tables so that the claimant becomes in effect the defendant and the original defamatory statements are amplified, repeated and backed up by overwhelming amounts of evidence, was the central objective of the defence. Moreover, the judge had ruled inadmissible Irving’s argument, to which he clearly attached considerable weight, that Lipstadt was part of a global Jewish conspiracy to discredit him, and allowing him to cross-examine her would also have allowed him to bring that argument back into play.

By relying on expert testimony, the defence hoped to overwhelm Irving with evidence that proved he was a Holocaust denier and a falsifier of historical evidence, and the film sticks fairly close to the actual events in court when it shows Robert Jan Van Pelt stumbling in the fact of Irving’s assault on the evidence he has assembled when it appeared that the holes in the Auschwitz crematorium roof through which canisters of Zyklon-B were dropped into the room below, where the body heat generated by the crowded Jewish victims would turn it into a deadly gas, killing them all, could not be seen in the photographs taken from above. The film shows Lipstadt in despair at this turn of events, and indeed everyone in the defence was taken aback and wondering what to do. In the film, it is only with difficulty that Lipstadt is persuaded that the experts will win out in the end.

And so the next day’s proceedings in the movie open as I step into the witness box and proceed to rescue the situation with a detailed demonstration of how Irving falsified and deliberately misinterpreted a crucial document, which is cleverly projected in large lettering onto the wall behind me (it was not in the actual trial, of course), to show how it was written in the old German script, known as Sütterlin, indecipherable to anyone who does not know, as Irving and I do, how to read it. This makes dramatic sense, and of course is very flattering to me, but it is grossly unfair to Van Pelt, who in further days of testimony redeemed himself and showed with absolute clarity and conviction that the holes in the crematorium roof were there even after the SS had blown the building up.

Where Van Pelt, an expert on the architecture, construction and operation of Auschwitz, presented testimony on these aspects of the Holocaust, and on Irving’s distortion and manipulation of the evidence for them, my role, as I have indicated, was to go through Irving’s writings and speeches to see whether they were falsifying the evidence in order to deny the Holocaust. Lipstadt’s memoir History on Trial accurately presents me at the outset, along with my researchers, as undecided: none of us had in fact read Irving’s work, which was popular history of a very empirical, or perhaps one should say supposedly empirical narrative kind – he was uninterested in the arguments and theories which are the stuff of undergraduate teaching, and so we had not even considered using them. But the movie presents us as ‘out to get’ Irving from the very beginning, which we were not. We simply did not know what we would

find.

We decided to take the evidence for 19 events or groups of events which according to Irving presented the only reliable and proven instances of Hitler’s attitude to, and role in, the Holocaust; every one of them, he claimed, showed Hitler was ‘probably the best friend the Jews had in the Third Reich’. We parceled them out amongst ourselves and set to work. Every couple of weeks we would have a meeting to discuss our findings. These were truly exciting occasions, as Nik or Tom would come in waving some papers and saying ‘you’ll never believe what he’s done here!’ As we went steadily through the evidence, we uncovered case after case of sometimes quite subtle manipulation of the evidence, all adding up to an overwhelming indictment of his methods. The movie chooses not to convey this sense of excitement and to a degree misrepresents our attitude, worryingly conveying the misleading impression that we were already biased against Irving even before we started work on the case. We were not.

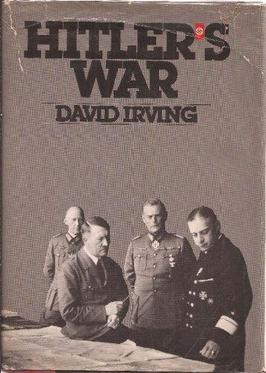

My own task also included assessments of whether Irving had a good reputation as an historian, a point which formed a significant part of his case, though in the end, for reasons I found hard to fathom, the judge ruled this irrelevant to the matter in hand; and, more importantly, whether or not he was a Holocaust denier. At one point Irving claimed that he was not a Holocaust denier because the Holocaust had never happened, and how could you deny something that didn’t exist, but the circular nature of this argument was obvious to everybody, and so it was disregarded. Much more important was the fact that he agreed with our definition of Holocaust denial, a definition extracted from the Holocaust denial literature that formed the basis of Lipstadt’s book Denying the Holocaust. This made it relatively easy for me: all I had to do was to comb through the material and find statements that conformed to the definition. I could also show that Irving’s Holocaust denial had hardened and become more extreme over the years, for example by comparing the first edition of Hitler’s War (1977) with the second (1992), where references to Auschwitz as an extermination centre had been replaced by its designation as a ‘labour camp’.

We also decided to go through Irving’s successive accounts of the Allied bombing of the Baroque city of Dresden in February 1945 as a kind of ‘control’, to see if he falsified evidence when he was dealing with subjects other than Hitler’s role in the Holocaust. This turned up a real gem. Irving clearly intended to present the bombing raids as morally and historically a crime equal to that of the Holocaust, so we found successive instances in his work of inflation of the statistics of deaths in the bombing, including, almost unbelievably, his use of a document he had a few years before dismissed as a falsification – a police report on the bombing giving the number of dead as 25,000 to which Joseph Goebbels’s Propaganda Ministry had added a ‘0’, making it 250,000, in order to impress neutral opinion and perhaps persuade some country such as Sweden to intervene to try and bring the war to an end before Germany was totally defeated. There were many other falsifications in his account, including the claim that Allied fighter planes had strafed people fleeing from the scene, along with a wholly unsubstantiated claim that there were hundreds of thousands of refugees in the city at the time of the bombing.

Memorial Museum | EUROM

The movie, obviously, had to leave out the great majority of the subjects we dealt with. It needed to be economical with the details, or audiences would soon get bored. It also needed to find imaginative ways of conveying the issues at stake. The courtroom proceedings consisted mostly of hours of tedium, interrupted only by brief moments of high drama. To bring out the issues with greater clarity, the film uses another character, Laura Tyler, a young paralegal assistant to Anthony Julius, played by Carmen Pistorius. Tyler was, and is, a real person, but while she mostly worked behind the scenes the film foregrounds her by showing her in conversation with her boyfriend Simon discussing the trial at various points, bringing a bit of youth and glamour into a movie peopled mostly by the middle-aged. The

defence team also travelled to Auschwitz itself, for a guided tour by Van Pelt, another excursion beyond the courtroom walls which served the dual purpose of showing the actual location of the crimes Irving denied, and providing Rampton with the evidence with which to attack one of Irving’s key claims.

Towards the end of the trial, the judge, Sir Charles Grey, alarmed the defence team by asking Rampton whether he thought Irving was sincere in his Holocaust denial. There was, to be sure, an element of the naughty schoolboy in Irving’s demeanour, cocking a snook at the Establishment and presenting himself as a kind of contrarian almost for its own sake. But, as Rampton reaffirmed, and the judge accepted, there was no doubt that Irving was a genuine racist, anti-Semite and Holocaust denier: so sincere was he, indeed, that he thought he was entitled to manipulate the evidence to conform to his own inner beliefs. Grey’s question was genuinely puzzling, and creates a moment of some drama in the movie.

Another incident towards the end of the court proceedings, was not included in the film, and that was when Irving inadvertently addressed the judge as ‘Mein Führer’. As the courtroom dissolved into laughter, and even the judge could not stop a wintry smile passing fleetingly across his face, I could scarcely believe what I had heard. Had he really said that? A few days later, back at my office in Cambridge after the trial had ended, I received a phone call from a psychiatrist who told me he was working on Freudian slips. Had Irving really said Mein Führer? he asked. Well, I thought so, I said, though I found it rather unbelievable. Yes, the psychiatrist said, he had asked the judge (who was unusually forthcoming on such matters) and Grey had told him that Irving had actually mumbled an apology amidst the general laughter. How did he explain the slip? I asked.

His theory was that Irving, born in 1938, had been traumatized by his father’s departure for the war to fight against Hitler, as his mother must have told him, and was so angry that he adopted Hitler as a father figure. At the age of four, his brother recalled him rendering a Nazi salute to German bombers as they passed over their Essex home on their way to bomb the London docks. For Irving, Hitler was a kind of benign authority figure, and so too was Mr. Justice Grey, who had indeed been exceptionally kind to him during the trial, suggesting questions to ask the witnesses and complimenting him on his knowledge of the law (so as to head off any possible appeal by Irving on the grounds that as a litigant in person without the benefit of legal representation or assistance he was at a disadvantage when confronting an experienced QC such as Richard Rampton). In the excitement of delivering his closing statement, Irving had confused the two men and addressed the judge as Hitler.

However plausible this might have seemed, it was clear that the filmmakers considered the incident too undignified and, on the screen at least, too inexplicable to show, and so it was omitted, along with many other dramatic moments in the proceedings. The film in general stuck commendably to both the spirit and the letter of the case. The issues at stake were serious ones, and by showing them from Lipstadt’s personal perspective, David Hare and the director Mick Jackson helped audiences identify with the fight against Holocaust denial that Lipstadt was waging. It conveyed complex legal and historical issues with admirable clarity, and it made clear that the court’s decisive ruling against Irving had underlined in detail the fact that Holocaust denial necessarily depended on the falsification of history and the manipulation of the documentary evidence.

It was also – and this does not come through strongly enough in the movie – a victory for freedom of speech. Some commentators thought that Lipstadt, along with Anthony Julius and his legal team, was trying to silence Irving. The reverse was true. Holocaust denial was, and is, not illegal in the UK. It was Irving, as a Holocaust denier, who was trying to silence Lipstadt. Had he won, she would have been forced to withdraw her book and the publisher would have been obliged to pulp all the copies in its possession. Bookshops would have been open to litigation had they stocked it on their shelves – and indeed the original Statement of Case by Irving had included four bookshops along with Lipstadt and her publishers, among the defendants, though mention of them was withdrawn before the trial began. No publisher would have dared to bring out any book or article criticizing Irving, saying he was a Holocaust denier, or claiming Holocaust deniers told lies. It would have been a disaster for freedom of speech.

As it was, a publisher who produced a British edition of a book in which an American historian, John Lukács, writing some time before the trial, accused Irving of denying the Holocaust and distorting the evidence, bowdlerized the text by softening the criticisms of Irving before bringing it out in the UK, and my own book on the case, already published in the USA, was rejected by six British publishers on the grounds that it risked incurring a libel suit from Irving, who was writing to publishers warning them that he would sue if they published it. Eventually it was brought out by a small left-wing publishing house, Verso, who, when asked if they were worried about being sued, replied that they would welcome a libel writ from Irving because it would give them the publicity they badly needed.

The trial, the books that came out of it (including the 350-page court judgment), and the movie Denial, struck an important blow against Holocaust denial. Irving had been taken seriously as a historian before the trial, but this was no longer the case afterward. But while it discredited Holocaust denial amidst an international blaze of publicity, its effects did not last long. The rise of the Internet and especially social media has given Holocaust denial a new lease of life. The struggle against it continues.