Laure Neumayer, University Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne

Cover picture: Tunne Kelam MEP (EPP Group, Estonia) speaking in the commemoration of the Baltic deportations at the European Parliament in Strasbourg | EPP Group

Since their inception, European organisations such as the Council of Europe and the European Union (EU) have celebrated the common past of their member states in order to provide a historical grounding for the European project and thus consolidate its legitimacy. After the Cold War, Europe’s ‘dark past’ was included in this heritage, and the Holocaust became the ‘negative founding myth’ (Leggewie, 2008) of the Council of Europe and the EU. Both organisations imposed a ‘mnemonic accession criterion’ on their future member states, which were required to critically evaluate their own complicity in this genocide and to give greater visibility to the commemoration of its victims. Meanwhile, in the former Eastern bloc, a historical narrative centred on the equivalence of Nazi and communist crimes was gaining ground. From the mid-1990s onwards, numerous anti-communist circles criticised the ‘incomplete’ character of the regime change which, they claimed, had allowed former communist leaders to evade justice and to maintain comfortable positions in society. In line with the paradigm of totalitarianism, a variety of politicians, academics and activists made crime the essence of the communist ideology. They portrayed the communist regimes as tyrannies kept in power by constant terror and devoid of any popular support, across all national contexts and historical periods.

Against this background, European organisations became venues where bilateral and domestic disputes over the past could be continued or amplified. One of the most conflictive issues was the retrospective assessment of communism, which sparked heated discussions in both the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) and the European Parliament (EP). Although the legacies of communism had been debated as early as 1992 at the PACE with respect to policies of lustration, the enlargement of the EU to include ten post-communist countries in 2004-2007 created new institutional venues in which to extract memory issues from their national frameworks. Representatives from the former Eastern bloc set out to renegotiate the boundaries of the legitimate European historical narrative by seeking equal treatment for Nazi and communist crimes in terms of historical reckoning, collective remembrance, and legal accountability. In debates at European level their interpretation of ‘Nazism and communism as equally evil’ started to compete with the Western European narrative that had made Auschwitz the standard of persecution and asserted the unique nature of the Holocaust (Littoz-Monnet, 2012).

In the literature, these mobilisations have been analysed as ‘claims for recognition’ (Closa Montero 2010) or attempts to set a ‘Gulag memory’ against a ‘Shoah memory’ (Droit 2007). Despite the indisputable ‘politics of recognition’ involved in these demands, these interpretations may suggest a binary opposition between ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ readings of the past. This would obscure both the ideological dimension of the conflicting assessments of socialist legacies across the continent and also the fact that the condemnation of communism provides conservatives with a strong symbolic advantage over the Left not only in Eastern Europe but in Western Europe as well. In addition, a detailed analysis of European-level debates on communism shows that they were not just the natural extension of the ‘memory boom’ that has affected Western countries since the 1980s, but the result of the combined action of a variety of memory entrepreneurs, who made specific claims in the national political arena as well as in European institutions (Neumayer, 2018).

Two competing visions of communism

During the numerous historical debates held at the PACE and in the EP after their respective enlargements to the East, two divergent ways of assessing communism and its comparability with Nazism were defended by representatives with distinct biographical characteristics and ideological references.

The first interpretation underlined the singularity of the Holocaust and historicised the analysis of communism. It distinguished several phases in the history of the socialist regimes, characterised by varying degrees of violence and different ways of enacting Marxist ideology. This was the line of argument of a group of representatives of the Left and the far Left from the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats and the European United Left groups, which rejected any similarity between fascism and Nazism on the one hand and communism on the other. This was also the prevailing discourse in the Russian delegation at the PACE, which defended a heroic vision of the ‘Great Patriotic War’ and of victory over Nazism, as well as among the communist representatives from southern European countries marked by recent dictatorships such as Portugal and Greece.

A second vision characterised communism by what was seen as its essence: namely, violence. It was considered an ahistorical project of great brutality, comparable with other outbursts of mass violence, notably genocidal, and demanded equal treatment for the victims of Nazism and of communism. This interpretation was mainly advanced by Central European representatives of the conservative Europe’s People Party and the liberal Alliance of Liberals and Democrats in Europe, joined by some Green representatives. The group brought together former dissidents and younger representatives who had entered politics since the transition to democracy. Its members placed particular emphasis on the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, under which the two dictatorships had shared out Central and Baltic Europe between them. From their perspective, this alliance placed Stalinism and Nazism in a league of their own among twentieth-century dictatorships and made their crimes equivalent.

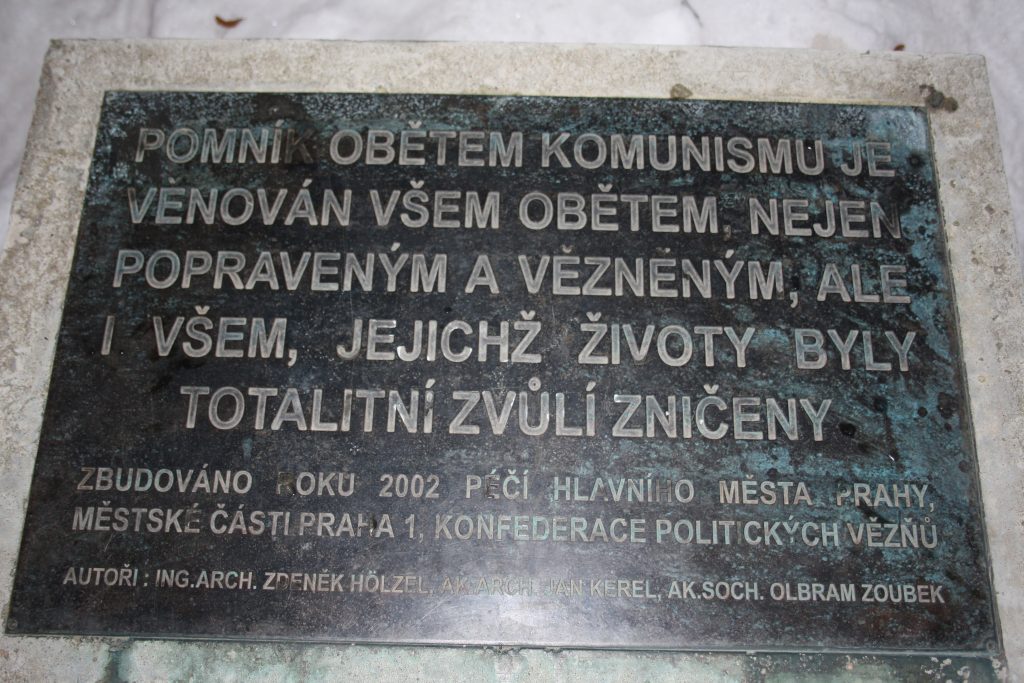

This analysis of communism, loosely based on the totalitarian paradigm, became hegemonic in both the PACE and the EP, which adopted several official parliamentary resolutions centred on the equivalence of Stalinism and Nazism. The most important of these texts are the PACE’s resolution of 2006 on the ‘need for international condemnation of the crimes of totalitarian communist regimes’ and the EP’s resolution of 2009 on ‘European conscience and totalitarianism’. In addition, the EP declared a new day of remembrance: 23 August, the date on which the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed in 1939, became the ‘Day of remembrance for the victims of totalitarian and authoritarian regimes’ in 2009. The requests to use criminal law to penalise the denial of ‘communist crimes’ and to establish an international court based in the EU to judge those responsible for these crimes were not met. But remembrance served as a substitute for the legal treatment of socialist mass violence with the creation, in 2007, of a new policy consisting in sponsoring projects that maintained ‘the main sites and archives associated with deportations as well as the commemorating of victims of Nazism and Stalinism’.

Before its expansion to the East, the EU’s main response to the legacy of dictatorships had been as part of heritage protection, via the provision of financial support for the conservation of Nazi death camps. A critical juncture came in 2004-2005, when the combination of low electoral turnout at European elections, the prospect of an unprecedented enlargement and the rejection of the Constitution project were understood as signs of the failure of earlier policies in the fields of culture and citizenship. The drafting of the programme ‘Europe for citizens’ by the European Commission provided a window of opportunity for Central European representatives eager to challenge the EU’s Holocaust-dominated official narrative by calling for the programme’s remembrance strand to cover not only Nazism but also Stalinism. After intense negotiations in different segments of the European institutions, the new public policy, designed to foster ‘active European remembrance’, began to address this previously ignored painful past.

This handling of the communist crimes at a symbolic rather than at a legal level prevailed because the commemoration of victims of mass violence was invested with different purposes by the actors involved. Whilst the European Commission and the EU Council saw it as an instrument supporting the development of democratic European citizenship, the EP considered it as a tool to build a common identity. For the anti-communist memory entrepreneurs, the extension of the scope of a pan-European historical memory was the recognition of the socialist experience as a ‘relevant past’ of Europe. All these interpretations were in line with the standards supported by the European institutions, such as overcoming historical antagonisms and protecting fundamental rights. Moreover, focusing on victims avoided controversies regarding the definition of totalitarianism and the ranking of different painful pasts, even though the steps to preserve the memory of the socialist crimes were largely modelled on those already in place to commemorate the Nazi atrocities.

The rationales of anti-communist mobilisations

Anti-communist mobilisations were led by a small group of representatives, primarily from the former Eastern bloc, who participated in all the debates on communism at the PACE and the EP, drew up official texts condemning communist crimes, and contributed to awareness-raising actions in the European assemblies or at their periphery. How can we explain the ability of these newcomers, who were still relative outsiders at the European assemblies, to impose an interpretation of communism that altered the dominant approach to historical memory in Europe?

Focusing on their sociopolitical profiles sheds light on the memory entrepreneurs’ biographical, partisan and ideological motivations, but also on the constraints placed on their mobilisations. The calls for remembrance of the socialist crimes and justice for their victims launched by mainly conservative or liberal representatives, some of whom had actively opposed the Soviet-type regimes, can be considered as an extension of their struggle at national levels to impose their view of communism, expose their opponents, or send a signal to Russia. However, most of these politicians were rather marginal members of the PACE and the EP when they entered these assemblies, and some of them were aware of the wide gap between their strong political capital at home and their relative insignificance in European arenas. The new representatives from the former Eastern bloc had to absorb the rules of the European parliamentary game in order to fully assume their role in the European assemblies. To acquire institutional credit and to influence parliamentary work, specific know-how was needed, such as the capacity to build coalitions, the ability to present admissible arguments and the willingness to comply with legitimate rules of interaction.

This initial marginal status was actually one of the driving forces of a project designed simultaneously to strengthen individual positions within European assemblies and to reshape European historical memory. Anti-communist mobilisations were a trial-and-error process characterised by a series of struggles and compromises with dominant Western conservative allies and left-wing opponents. The memory entrepreneurs’ gradual mastery of European roles, acquired i.a. through their engagement in the anti-communist cause, exemplifies a broader process of professionalisation of the newly elected PACE and EP members. European assemblies were therefore an echo chamber for demands, related as much to the memory entrepreneurs’ militant backgrounds and their political affiliations as to their decision to embark on a European career.

The analysis of this unlikely mobilisation provides three main insights into the politics and policies of the European memory.

First, despite their geographical and ideological homogeneity, anti-communist memory entrepreneurs present different sociopolitical profiles depending on their previous national and European political trajectories. Some of them were former leaders of the opposition to communism, others belonged to an ‘anti-communist young guard’ who had come into politics during the regime changes, while a third group comprised peripheral actors who had begun their European careers with little political experience. Their respective political resources entailed different ways of approaching their European term of office, while the importance they attached to their European mandate, depending on the point in their career at which it occurred, defined their commitment to the anti-communist cause. Only the representatives initially equipped with considerable resources, such as well-known former dissidents, or those combining strong national political capital and relevant European expertise, managed to achieve re-election as MEPs. This circumstance shows that the mobilisation of memory as a source of political capital is insufficient on its own; a contender wishing to make their mark on the European stage must also possess the requisite political skills.

Second, the rationale of European-level political debates and policies for managing painful pasts diluted the anti-communist cause into a broader condemnation of all types of dictatorships that befell Europe in the twentieth century. The rules of European political competition entail attempts to mitigate ideological conflicts and to denationalise issues, in order to build broad coalitions across parliamentary groups and national delegations. But anti-communist representatives, who overwhelmingly belonged to the Europe’s People Party, faced fierce ideological opposition from their peers in the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats and in the European United Left. In 2008, the Social Democrats even set up a History Working Group at the EP with the explicit goal of ‘countering any attempts to rewrite history’.

Anti-communist memory entrepreneurs were also forced to adjust their claims to the normative beliefs that underpin the existing EU policies for managing painful pasts. Their demands were at odds with the patterns of remembrance established in the West in the 1970s and consecrated by the EU in the 1990s. Their request for the acknowledgement of their own suffering, in their view wrongfully ignored, was at odds with the ‘politics of regret’ favoured by Western governments (Olick, 2007), which amounted to admitting past wrongs and asking for the victims’ forgiveness. The will to impose a single narrative as a historical truth across the whole continent collided with the ‘multi-perspective’ history promoted by the European organisations, which admitted the plurality of points of view on the past as long as they were founded on an objectively established factual basis. Moreover, including historical episodes other than World War II among the relevant pasts of Europe questioned the significance of the Holocaust as the founding event of the continent’s history. The memory entrepreneurs’ vision of socialist crimes was structured by a ‘mimetic rivalry’ with the Judeocide (Laignel-Lavastine, 1999). Denunciation of the ‘amnesia’ and the ‘amnesty’ regarded as surrounding communist crimes called into question the unique character of the Nazis’ attempts to exterminate the Jews, which allegedly obscured the full comprehension of other mass violence. As a result, anti-communist memory entrepreneurs were regularly accused by their political competitors and by militants of the Jewish cause of trivialising Nazism and of minimising the complicity of Eastern European societies in the Holocaust. Last but not least, their mobilisations also prompted calls for the recognition of the acts of other non-democratic regimes, such as Francoism in Spain and other southern European military dictatorships.

Vip Ciacci via Wikimedia Commons

Paddy via Wikimedia Commons

To comply with these many constraints, anti-communist memory entrepreneurs adjusted their cause to the human-rights paradigm that structures the politics of memory at European level. They called on European institutions to assess socialist legacies with the same criteria as those applied to other dictatorships, which would entail denouncing the crimes against humanity that were perpetrated and commemorating their victims. However, moving to this level of generality to some extent diluted the anti-communist cause into a blanket condemnation of ‘all forms of totalitarianism’ that had existed on the European continent, thereby tempering the communism-Nazism equivalence.

Third, the existing European remembrance policy and the segmentation of the European political space devalued the parliamentary resolutions outside the PACE and the EP, thus diminishing the national political benefits and the legal and judicial implications of the anti-communist discourse endorsed by these assemblies. European remembrance policies drawn up by the EU and the Council of Europe in the 1990s had left member states free to manage their painful pasts by means of law, without imposing any legal instruments regarding the fight against denial or the prosecution of perpetrators. Besides this lack of a legally binding legislation, anti-communist mobilisations were further hindered by the fragmented nature of the European political arena. Their attempts to extend the effects of anti-communist parliamentary resolutions to national political contexts and to convert them into European-level public policy and legal action were only partially successful.

The fading of European-level anti-communism?

In 2006, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe refused to give any specific content to the PACE’s condemnation of communist crimes. This prompted the memory entrepreneurs to intensify their involvement in the EP, which picked up the anti-communist discourse developed at the PACE and called on the EU to give it the support the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe had denied. Several unsuccessful attempts were made, between 2008 and 2010, to have the PACE and the EP label the Ukrainian Great Famine of 1932-1933 as ‘genocide’. But the anti-communist cause undoubtedly lost its prominence, even in the EP, after the adoption of the Resolution on European conscience and totalitarianism in April 2009.

No parliamentary resolutions have been adopted since then. In 2013, the report on ‘Historical memory in culture and education in the EU’ tabled by the Polish representative Marek Migalski was rejected by the EP Committee on Culture and Education even before it could be discussed in the plenary session. Although the remembrance strand of the programme ‘Europe for Citizens’ epitomised a shift in the official understanding of Europe’s ‘dark past’ to encompass Stalinist mass violence, it fell short of the ultimate goal of most anti-communist memory entrepreneurs, namely the adoption by the EU of legal steps to prosecute former high-ranking communist leaders. In 2013, the citizenship programme was renewed and its remembrance strand was strengthened. This institutionalisation of Community remembrance policy can be seen as a success of the anti-communist memory entrepreneurs. But its scope was extended to initiatives that ‘reflect on the causes of totalitarian regimes in Europe’s modern history (especially but not exclusively Nazism which led to the Holocaust, Fascism, Stalinism and totalitarian communist regimes) and to commemorate the victims of their crimes. The strand will also encompass activities concerning other defining moments and reference points in recent European history’. This attenuation of the symmetry between Stalinism and Nazism highlights the contraction of the memory entrepreneurs’ room for manoeuvre: the controversy over communism had lost its intensity in European assemblies, while the European Left had capitalised on the condemnation of communism to obtain the same for an ideology against which it primarily defined itself, namely Fascism.

In order to keep the issue of communist crimes on the EU’s agenda and to prevent the dilution of the cause into a broad anti-totalitarian discourse, anti-communist representatives still carry out awareness-raising activities (exhibitions, film screenings, conferences and hearings) about socialist crimes. They created two overlapping transnational networks, the EP informal groupings ‘Reconciliation of European Histories’ and the ‘Platform of European Memory and Conscience’, in order to coordinate claims for recognition and prosecution, at the EU level, of gross Soviet-era human rights violations. Geographically and ideologically, however, the membership of these networks is very homogeneous, and this low representativeness limits their capacity to turn their demands into politically audible requests in the broad European political space. Because their vision of Europe’s experience of dictatorship is heavily centred on the socialist period and does not allow for the confrontation of different interpretations of communism, their activities appear politically biased. As a result, their impact in the EP is limited to a very specific segment – the post-communist conservatives – while their symbolic resonance in the general public is restricted to the former Eastern bloc.

On the European continent, the remembrance actions dedicated to the victims of socialist crimes are far less visible than the tributes to the victims of Nazi atrocities. It is very telling that 23 August, established in 2009 in the EU as ‘Day of Remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes’, failed to gain the same symbolic significance as the ‘International Day of Commemoration in memory of the victims of the Holocaust’ on 27 January. Although the EU Commissioner in charge of remembrance makes a speech every year on 23 August, official commemorations are organised in only nine member states, most of them countries directly affected by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Despite their ongoing mobilisations, therefore, the vision of history put forward by anti-communist memory entrepreneurs will have a regional, rather than pan-European, significance.

Almost 30 years after the fall of socialism, mimetic rivalry still permeates European-level historical debates, which remain structured around two diverging accounts of the past. In the first, the Holocaust is seen as a unique form of mass violence and as the negative symbol of a ‘new Europe’ based on protecting human rights; while the second demands, in the name of the universality of human rights, that the gravity of socialist crimes be recognised as equivalent. In an attempt to find a middle ground between these two narratives, the EU and the Council of Europe have produced a historical memory based on a broad denunciation of ‘all forms of totalitarianism that existed in Europe in the 20th century’ and on the commemoration of their victims. The very fact that this under-specification was necessary to avert controversies over the rankings of different painful pasts confirms that the European-level discussions have not put an end to the heated debates on the comparison of the Holocaust with other forms of mass violence. Quite the opposite, in fact: the controversy over communism, which tests the European institutions’ capacity to produce a consensual historical narrative while integrating new states, illustrates the persisting difficulties of establishing common ground for a shared culture of memory on the European continent.

References

CLOSA MONTERO Carlos (2010) “Negotiating the Past: Claims for Recognition and Policies of Memory in the EU”, Working Paper 08, Madrid, Instituto de Politicas y Bienes Publicos, CCHS-CSIC.

DROIT Emmanuel (2007) “Le Goulag contre la Shoah. Mémoires officielles et cultures mémorielles dans l’Europe élargie”, Vingtième siècle, 94, pp. 101-120.

LAIGNEL-LAVASTINE Alexandra (1999) “Fascisme et communisme en Roumanie : enjeux et usages d’une comparaison”, in Stalinisme et nazisme : histoire et mémoire comparée, edited by Henry Rousso, Brussels, Editions Complexe, pp. 201-247.

LEGGEWIE Claus (2008), “A Tour of the Battleground: The Seven Circles of Pan-European Memory”, Social Research 75, pp.217-234.

Littoz-Monnet, Annabelle (2012), “The EU politics of remembrance: Can Europeans remember together?”, West European Politics, 35(5), pp. 1182–1202.

NEUMAYER Laure (2018), The Criminalization of communism in the European Political Space after the Cold War, London, Routledge.

OLICK Jeffrey (2007), The Politics of Regret, On Collective Memory and Historical Responsibility, London, Routledge.