Clémentine Deliss, Global Humanities Professor in History of Art at the University of Cambridge, Guest Professor at Städelschule, Frankfurt, and Associate Curator at KW Institute for Contemporary Art Berlin

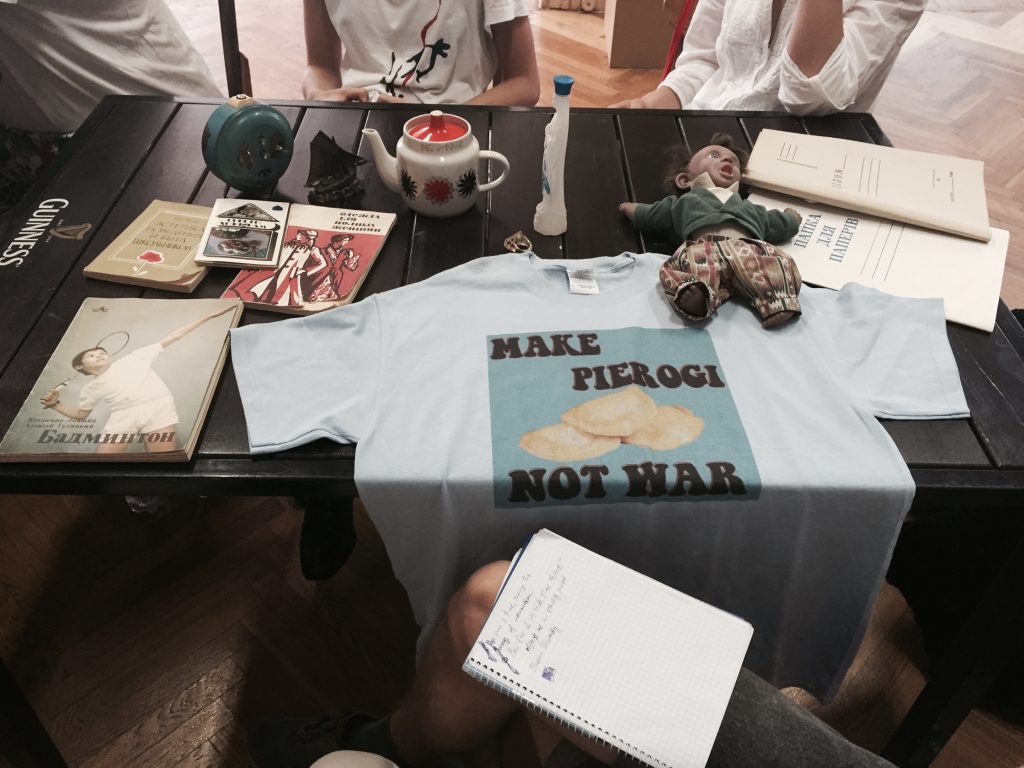

Cover image: Metabolic Museum-University, Ljubjlana 2019. Photo by David Kunc

What I shall present below represents the current state of my work on counter-conduct as a performative instance, and academic iconoclasm as a methodological stance, and their significance for decolonial exercises performed as part of the redeployment and interpretation of museum collections. This is connected to models for a Metabolic Museum-University (MM-U) that I have worked on since I left the Weltkulturen Museum in 2015. I have been seeking to develop a new cross sectoral method of interpretation by bringing the university into the space of the museum, and thereby translocating roles and practices. The background to this work can be found in condensed form in “The Metabolic Museum” (Hatje Cantz 2020, Garage Museum 2021).

The first exercise toward a museum-university took place in 2015 in Kiev at the Museum of the History of Ukraine. It involved a group of self-elected citizens who chose to accompany me to the flea-market. There they searched for artefacts of ‘contention’. Back at the Museum, we installed a table and several chairs in the entrance. Visitors were invited to take part in the elucidation of the diverse objects that had been purchased, and unpack their ambivalent and problematic meanings. A further model was developed with students at the University of Art and Design, in Karlsruhe. It was presented at the 33rd Biennial of Graphic Art, in Ljubljana, in 2019. Chairs were customised with small projectors so that visitors could “spam the hang”, projecting their own archival images between the paintings. During the sessions of the MM-U, a young faculty presented a wide range of lectures, which were attended by unsuspecting visitors. The result was rewarding for the museum, the participants, and the public. The latest model of the Metabolic Museum-University is being developed at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, and is based on a reassessment of Berlin’s collections.

Alongside demands for restitution, collections in museums of the global north have become toxic witnesses to genocidal practices. Ethnology’s claim is that it salvages the past but what it relies on and renews is the destruction-reconstruction reificationscarcity sequence that we are currently witnessing through historicizing provenance studies–effectively going back to what was not written down when the objects were acquired, stolen, bought, or gifted, and subsequently inserted into an ethno-logical taxonomy, including race-led arguments and the ideology of conservation. Ultimately, ethnology has produced a cult of possession, an obsessive focus on determining and unravelling life’s unknowns embodied in the religious objects of other people and embedded within the violent and racist dramaturgy of ethnographic museology.

Recent bio-medical analyses of collections are currently being performed in ethnographic museums using the same equipment deployed for human beings. This new “inner voyage” reveals initial knowledge about quasi digestive tracts carved or incised into solid wood by the artist, providing small ducts to be filled with content by a shaman or priest. I would argue that this is an infringement of ethical and intellectual rights for which the museum is to be held responsible. It cannot own the sole rights for reproduction! For indeed, ethnographic collections can be read as a library of organs, the vital matter, so to speak, of Black lives, and are significant repositories that need to inform decolonial practices, from art to design and engineering, and their respective epistemologies. Sadly, most, if not all museums, hinder physical access to their collections, thereby denying contemporary remediation and defining the conservationist role of the custodian or curator more than ever before.

This is where a methodology of academic iconoclasm supports the debate on the decolonial. Here, I wish to distil iconoclasm from its usual art-historical references 1, and retain the struggle it evokes for shifts in meaning and method, for new techniques that dislodge concepts of the masterpiece, the master narrative, the master institution (university, museum, academy) and their respective distinctions. Academic iconoclasm is the wilful suspension of normative discursive and architectonic structures that inscribe epistemic, bureaucratic, and legal rules to police others working with public collections. It is a form of counter-conduct that blankly refutes disciplinary departments inherited from 19th-century European scholasticism. In the words of Nigerian Nobel prize winning author Wole Soyinka, it defies “species narcissism” or in those of British-Nigerian artist Onyeka Igwe, it requires “finding illegitimate ways of knowing”. In a series of seminars held at the College de France in 1977-1978 entitled “Security, Territory, Population”, philosopher Michel Foucault describes counterconduct as the first instance of critique and the “art of not being governed quite so much.” In the context of the museum, counter-conduct evokes a tension between emancipation (for example, from the yoke of consumerist exhibition-making, or the stultification of the art historical canon), and revisionism with the unabashed return of the universal museum for which the new Humboldt Forum in Berlin is a case in point. This ambivalence makes it confusing, as counter-conduct transports both the exhilaration of a defiant position, and the fear that resistance can turn into public-facing demagogy.

As a methodology of research, academic iconoclasm generates a heteroclite set of artefacts and artworks and constructs relationships of transgressive adjacency between them. These incite disorder in existing taxonomies and promote discordant readings, be this in terms of history, body politics, gender, race, ethnicity, or diversity. It creates assemblages or constellations of such materials that together work to suspend the canonical reliance on context, and the specialism of the expert. At KW, I have put together a faculty that includes artists working in different media, situation designers, a composer, a lawyer, a novelist, and a feminist anthropologist. We work to develop a new set of analytical parameters by observing and discussing aggregates of ambiguous objects, artworks, and ephemera from different collections in Berlin.

Meanwhile, just as strategies and form of control are updated and technologized, dissidence can acquire an anachronistic tinge. Terms like underground or subculture lose their salience and colloquialism, no longer evoking the seditious zeitgeist of the moment. If the European avant-garde and institutional critique of the 20th century deployed tropes of conceptual and performance art alongside agitprop, today’s broader manifestations of the decolonial are affiliated to ever-increasing demands for accountability and self-representation. Art has become an extended debating chamber voicing controversies beyond walls and across disparate worlds, yet with very palpable consequences.

Museums are urged to negotiate acute disparities in employment equity, and to respond to demands for the returns of significant cultural heritage, extricated, albeit with some controversy, from an original environment and system of ownership. The falling of monuments, the defamation of board members and patrons, disputes over divisive appointments, petitioning, the wrangling around the new ICOM definition of the museum, the competition in Europe for being the fastest driver on the track of restitution politics; all of these situate critique within the broader public realm. Increasingly under scrutiny, the tax funded museum monitors itself in relation to tightening protocols of behavioural management, economic imperatives, curatorial normativity, for which communication with consumers is regarded as paramount. At a moment when artists are pushed to provide transparency and follow a common standard, transgressive, even heretic, exercises in radical dialogical thinking are necessary, but they cannot be easily shared with the public in the first instance.

Not responding to the command of public visibility and institutional auditing constitutes another form of counter-conduct, potentially suicidal when it comes to grant applications and funding, both individual and institutional. The refusal to respond to public transmission as required can constitute a stance, a Haltung, that is conceptual, aesthetic and form-giving, not to mention political. The museum in a post-pandemic context dispenses social medicine but it requires protection backstage, not front of house, in order for this complex institution to survive. This is counter-conduct as necessary askesis, as willful “communicational abstinence”, claiming the right to non-disclosure, to holding back contextual information. As Luke Willis Thompson, artist and faculty member of the MM-U asks, «Does digital hypervisibility serve the decolonial work we undertake? How can the institution become a channel for artistic interference and classificatory transgression?»

What becomes clear as we proceed is the potential overlap between counter-conduct and the decolonial. Both reflect pressure exercised on the body. Both are time-bound, and contingent on place and history. Both ignite emancipatory exercises in unpredictable methodological arenas. From the literary, archival approach of “critical fabulation” (Sadiya Hartman, Christina Sharpe’s Wake Work), to the “sonic support” of artist Abbas Zahedi, and “quietism” of “Shy Radical” Hamja Ahsan, these positions demand a corporeal, ergonomic adjustment from the museum, a concern for the public’s ease, and the time that can be spent sitting and studying in the museum. «A body must be at stake for an exhibition to become legitimate» argued artist Abbas Zahedi recently.

Remediation corresponds to this decolonial procedure: it proposes a reconfiguration of collections and practices of display that expose, transfer, and propagate meanings and agency, while slowly addressing the violence inherent in the museum as a structure of holding. In his manifesto for Aspergistan, titled “Shy Radicals. The antisystemic politics of the militant introvert”, Hamja Ahsan describes “culture” in a set of articles of which the following two ring particularly true: «The state shall guarantee twenty-four-hour access to all public libraries, museums, laboratories, book shops, tea and coffee houses, archives and cathedrals within its sovereign territory… The state guarantees twenty-four hour access to all objects of artistic, historical and cultural value.» (p. 24, Chapter 5, Bookworks, 2019).

The question is, in what way can we introduce a certain heresy or counter-conduct into the process of knowledge production. Because if we just follow academically sanctioned forms of analysis, we are employing taxonomies that stem from colonialism, and with them, clear traces of racism, capitalism, and extractionism. When I talk about the decolonial, it is about chiselling away at these disciplinary borderlines, hence the position proposed by academic iconoclasm. This is where the potential can be found in icono-clashing the procedures of the museum with that of the university –in particular, the architectonics of the building– how space is used –for example, the division between storage and exhibition, as well as the academic and curatorial inscription of collections into a time frame of permanent and temporary shows. For nothing any longer should be seen in disciplinary isolation, or be caught in the rut of academic divisionism and atomisation.

I wonder whether new formulations of higher education might extend more aggressively across the museum, the art school and the university? Imagine how storage depots could become like a greenhouse for the diasporic and trans-disciplinary student body to nurture and curate constellations out of diverse collections? Just like the interdependencies of the human metabolism, nothing would be seen in isolation; it would become a reflection of temporary mutualities between artworks, people, objects, media, experiences, observations, laws, economies, climates and affects that challenge the exclusive monopolies of the museum and university to produce and control new diasporic knowledge, including visual representation. Moreover, today we can feel the palpable antagonism and impatience when adjacencies are performed that bring analogue materiality with its slow, stubborn permanence in proximity with digital speed. Frustration can often lead to a turn toward the immaterial, rendering collections practically obsolete except for heritage studies.

I would argue that all museum collections are like the liver, the earliest divinatory medium known to humankind. Everything passes through the liver; it is like the imprint of a relational experience. To be read as oracular, liver-like collections need to be excised from their existing corpus or discipline in order to acquire contemporary intersectional meanings. For these to emerge or be revealed, the liver has to be placed within a set of circumstances and problematics that can provide a symptomatic analysis of the future. For example, a country goes to war, a person battles with another, a family seeks solace after death, all look for a route to the future. The organ, removed from its pulsating environment, becomes the testimonial that will lead to the enactment of human agency. Collections are also ominous vital organs for future knowledge. Their value lies in their mediatory potential and their diversity. While collections may denote the nomenclature of a given museum (art, natural science, anthropology, etc.), their semiotic and semantic potential exceeds this.

Academic iconoclasm incorporates a diagnostic, ergonomic, and agonistic stance. The diagnostic is the subject’s alertness to changing conditions, the ergonomic speaks of the awareness of the subject’s body, and the agonistic refers to the subject’s mood of engagement and critique. Aspects of counter-conduct can be read in how we deploy ourselves in the museum and how we are made to engage with existing curatorial models, and their underpinnings in the canons and industries of art history, ethnology, or the sciences. Counter-conduct also incorporates the subjective, the unfinished, the diffuse, and the desire to stimulate another kind of focus, in our case, on what can be done with historical collections, how they impact on different people’s lives, and how we can coax (or coerce) museums into becoming agents of inclusive transdisciplinary knowledge production for future generations. The democratic intellect is embedded within this process. It positions itself against specialisms.

Perhaps the questions we are looking for will come up once we have brought sufficient contentious materials together in both a prophylactic and iconoclastic manner. With contention, there is something that is both unclassifiable and which shouldn’t be spoken or shown. And this goes to the heart of the colonial problem, the “nefandum”.

Footnotes

- Finbar Barry Flood describes iconoclasm as follows “Derived from the Greek eik∫noklasts (eik∫n “likeness” + klan “to break”), first documented in eighth-century Byzantium, the term iconoclasm entered the lexicon of European languages only through the Latin iconoclasmus late in the early-modern period (Bremmer). In modern scholarship it has assumed a capacious character and can refer to the defacement or destruction of artefacts, buildings, images, or inscriptions. See Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol.3, Iconoclasm.