Celeste Muñoz Martínez, Lecturer in the History of Africa, University of Barcelona

Cover picture: View of the room Rituals and Ceremonies, Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale | © MRAC, Tervuren, photo Jo Van de Vijver

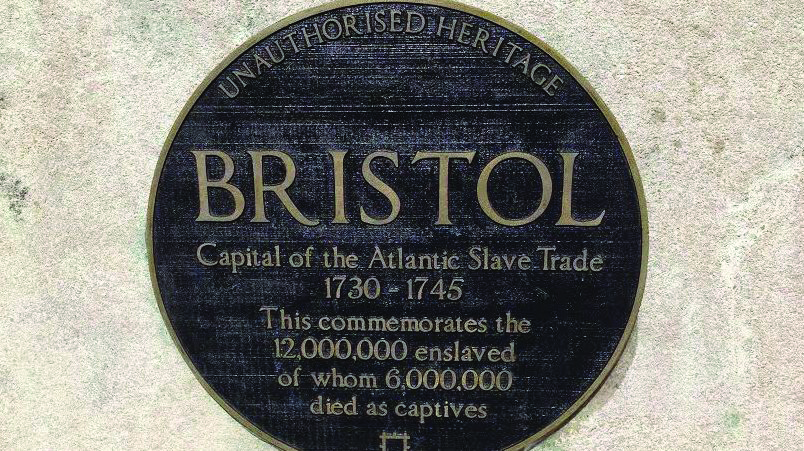

In 2006, then British Prime Minister Tony Blair caught the world by surprise when he issued an unprecedented apology for Britain’s part in the Atlantic slave trade, which he characterised as a “crime against humanity” [1]. This conceptual category, according to William Schabas (2012: 51-53), developed precisely in the context of the abolition of slavery and early colonialism, and even though it is now accepted by the United Nations to describe the slave trade and apartheid, the nations involved have rarely voiced a mea culpa. A year later, in 2007, the city of Liverpool, which had been the epicentre of the Crown’s slave trade in the eighteenth century, opened the International Slavery Museum to commemorate the bicentenary of the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1807) as a way to acknowledge this uncomfortable past. Step by step, Britain moved forward from words to deeds. These actions, however, were not nearly enough for many African nations and especially for Afro-descendant communities, who have called not only for economic reparations for the families of victims of racism and structural socioeconomic exclusion, but also for more forceful condemnation [2]. In this respect, it is legitimate to ask: if British slave-owners received compensation after abolition in the form of a multi-million pound loan that was not paid off until 2015, paradoxically with taxes collected from many of the descendants of the slave trade, then why not pay reparations to the victims today?

In these processes, the Afro community has certainly played a key role and is now a political subject in the construction of “transnational memories” (Assmann, 2014), which also call for a major review of the colonial past in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. One aspect made visible by the controversial remarks made by a later British Prime Minister, David Cameron, when he called Nelson Mandela a “hero” on the day of his death, is the omission of the Tory Party’s backing for the apartheid regime and for the South African leader’s labelling as a “terrorist” under Margaret Thatcher. A petition demanding a public apology was then signed by thousands of people, headed by decolonial activists intent on showing this nationally uncomfortable past to Europe. The decolonial trend of the twenty-first century, however, is not confined to British soil: it is a global movement that is becoming increasingly more vocal (Reyes, 2016).

In France, Emmanuel Macron, the President of the Republic of égalité and fraternité, set off a political firestorm when, in February 2017, he declared that French colonisation had been a “crime against humanity” and issued an apology to Algeria, where he was on tour, for past acts. His statements disturbed a portion of the French political class. Even though a decade had passed since Tony Blair’s remarks, the intervening years had clearly not resulted in a normalisation of imperial mea culpas, which still wounded a European identity built out of acting as a guardian of democracy and human rights [3]. As the historian Pascal Blanchard (2019) has sharply criticised, sixty years have gone by since the independence of France’s colonies and France still has not engaged in any reflection on its colonial past, nor has it opened spaces dedicated to the subject in a country with well over 10,000 museums and a host of collections brought from its overseas colonies.

On the other hand, the case of the Musée Royal d’Afrique Centrale, which was opened on the outskirts of Brussels in 1897 during the reign of Leopold II, recalls other heated debates on heritage and its use. The museum is located in an ostentatious palace that contains over 120,000 items plundered from the Congo, and it has been (and still is) one of the leading spaces for the glorification of colonialism and racism. Not until 2018 did Belgium conclude a critical review of the museum’s collections and galleries, which had remained unchanged since the nineteen-fifties and therefore continued to uphold painful racial hierarchies and discourses of black “primitivism”. The review, however, was not enough for the United Nations, which urged the Belgian government to issue a public apology for atrocities committed in the Congo and linked the country’s present-day racism against Africans to its meagre review of its past, publishing a report with 72 recommendations (United Nations, 2019). In addition, thousands of kilometres from Belgium, the Congolese themselves continue to argue that decolonisation will only be possible through restitution. To this end, Joseph Kabila, the controversial former president of the RDC, has repeatedly called for the return of the museum’s objects to Kinshasa. In this respect, restitution and economic reparations, together with symbolic apologies, are becoming the key pillars of today’s demands for historical memory of the colonial past, both in Africa and in Europe.

© MRAC, Tervuren, photo Jo Van de Vijver

Portugal, too, waded into controversy in 2018, when it announced that a new museum slated to accommodate the history of Portuguese colonialism was to be called the Museu das Descobertas [in English, Museum of Discoveries]. In response, historians and civil society nationwide came out staunchly against the initiative because the language evoked the authoritarian reign of Salazar and because it perpetuated a history of putting the Eurocentric subject at the centre of the story, since surely the first people to discover Africa or the Americas were their original inhabitants. Indeed, the Portuguese case has been defined as “amnesiac memory” (Cardina, 2016) arising from the social trauma caused by the bloody colonial wars that raged between 1961 and 1974. The lack of public and institutional initiatives, however, has not impeded the literary boom of the past decade, which has contributed significantly to the recovery of the “history” of Portuguese Africa. In the end, the political silence has been overtaken by the proliferation of publishers, output of academics and initiatives of civic engagement, which once again have come primarily from migrant and Afro-descendant groups. In 2017, for example, the Djass Associação de Afrodescendentes successfully launched a popular legislative initiative to gain approval for the construction, in Lisbon, of the country’s first memorial to the victims of slavery, which has yet to break ground as a consequence of political resistance.

The Spanish case shares many parallels with the Portuguese case. In Spain, however, the amnesia is not only institutional, but also collective. If Spain had a colonial past in Africa, it is generally unknown even in academic circles as a consequence of a policy of “reserved material” (1969) and a well-established Americanist tradition (Muñoz, 2017). The Spanish colonial enterprise has always been linked to the Americas, underpinning an identity of “hispanidad”—the “Spanishness” of the whole Spanish-speaking world—that was prevalent during the Franco dictatorship and remains so even today. Not only has no political apology yet been issued, but the glorifications of Spain’s colonial past have become normalised. Only a few months ago, Spain’s current foreign minister, Josep Borrell, made the following statement: “España no va a presentar esas extemporáneas disculpas que se piden, parece un poco raro que en este momento se plantee pedir disculpas sobre acontecimientos ocurridos hace 500 años” [in English, “Spain is not going to offer the untimely apologies that are being requested, it seems a little odd now to call for apologies about events that happened 500 years ago”]. Borrell’s remark came in response to requests from Latin American leaders and reflected his own bafflement [4]. At the same time, revisionist theses proliferate under the auspices of public institutions. These include arguments put forward by the philologist Elvira Roca in her book Imperiofobia [Empire-phobia] (2016), where she depicts Spanish colonialism as humane and claims there is no need to undertake any national self-questioning. For the African case, it will be necessary to wait for the decolonisation of the archives and for educational socialisation in order to examine Spain’s role in the Atlantic slave trade and the contemporaneous occupation of the territory. Doubtless, this process will also be pushed forward by Afro-descendant communities, for instance, through legal challenges such as the one instigated almost thirty years ago in Banyoles (Girona). The case in question, which involved the desiccated remains of a Bushman on display in the Darder Museum in Banyoles, was the focus of a decade-long battle between a Haitian physician Alphons Arcelin along with other Africans and a Catalan society reluctant to examine its own racism. The Bushman was not removed and buried in Botswana until 2001, when he was given a veritable state funeral that was mounted as a symbol of restitution for the sorrow and grief of colonialism. The Darder Museum, by contrast, did not undertake any critical reformulation of the space.

Obviously, Europe’s past involvement in the slave trade and colonialism is today a history of festering wounds. The continued existence of the trauma is a direct consequence of a management approach that still falls short in terms of reparations for victims and political accountability. The narratives of this latent conflict are closely bound up with the growth of xenophobia and the rise in populist discourses of hate. The structural omission of this “uncomfortable” past has confronted European identity itself, which has been challenged by diaspora communities calling for a decolonial review of public space, of representations of otherness and of national histories (Huyssen, 2003). The issue is one of “transnational memories”, which are built out of multiple geographical and social experiences that include the slave trade, colonial occupation and post-colonial Africa on the move, and which have given shape to subaltern identities. Coming out of this dialectic are demands that challenge the normalised colonial heritage of our museums and streets, while also calling for justice for crimes that are still kept quiet. These demands have been answered with varying degrees of success by the institutions and political authorities that are directly concerned, situating any progress or resistance on a battleground where, based on the trend of the past decade, voices will continue to be raised in support of a colonial memory that is both critical and unvarnished. Discussions and solutions need to happen with greater speed, involving every social agent, in order to look together at the past and build a better social harmony in the present.

Footnotes

1 “Blair fights shy of full apology for slave trade” in The Guardian (27 November 2006).

2 Kuba Shand-Baptites, “While the US debate heats up, why won’t the UK even talk about reparations for slavery?” in The Independent (17 July 2017).

3 «En Algérie, Macron s’excuse pour la colonisation, une ‘faute grave’ pour la droite» [in English, «In Algeria, Macron apologises for colonisation, a ‘grave error’ for the right»] in Le Parisien (15 February 2017)

4 «Borrell on the letter from López Obrador: ‘España no va a presentar esas extemporáneas disculpas que se piden’». [in English, “Spain is not going to offer the untimely apologies that are being requested”] in ABC (26 March 2019).

References

ASSMANN, Aleida. “Transnational memories”. European Review, 2014, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 546-556.

CARDINA, Miguel. “Memórias amnésicas? Nação, discurso político e representações do passado colonial” Configurações. Revista de sociologia, 2016, no. 17, pp. 31-42.

HUYSSEN, Andreas. “Diaspora and nation: Migration into other pasts”. New German Critique, 2003, no. 88, pp. 147-164.

Informe de las Naciones Unidad sobre el museo colonial de Bélgica: https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24153&LangID=E

MUÑOZ MARTINEZ, Celeste. “África en nuestros archivos: la historia que aún no puede ser contada” en La necesidad de conocer África. Dykinson, 2017. pp. 129-140.

REYES, Abdiel Rodríguez. “El giro decolonial en el siglo XXI” Revista Ensayos Pedagógicos, 2016, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 133-158.

SCHABAS, William, Unimaginable Atrocities – Justice, Politics, and Rights at the War Crimes Tribunals, Oxford University Press, 2012 – pp. 51-53.