We never quite know what to do with memorials. Sometimes we debate whether to tear them down or not, or even consider turning them into outdated memory centres which have proven useless time and time again, beyond allowing the government of the day to draw a line under the matter.

On 27 April 2024, the doors of the new national museum were opened. The President of the Portuguese Republic, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, presided over the official ceremony as part of the 50th-anniversary celebrations of the Carnation Revolution. Half a century after the prisoners were freed, the terrible Peniche Fortress has finally become an essential museum for understanding the longest dictatorship in Western Europe and celebrating the Portuguese people’s fight for freedom.

The participation of Spanish women in the French Resistance remains one of the great unresolved issues in the historiography of Republican exile and the Second World War. For decades, researchers and activists on both sides of the Pyrenees have denounced their neglect by both academia and society, an assertion that is now largely untrue. In recent years, the growing concern for gender issues and women’s history has led to a greater public presence and their inclusion across the board in the most recent research. However, there are still no specific studies of this particular group of women, largely due to the problem of the limited availability and fragmentation of sources, as well as the way in which they have been constructed in memorials since 1944.

The architectural and artistic heritage of Forlì includes a work of great value, both from a cultural and historical point of view – the mosaics in the former Aeronautical College, now a school for 11–14-year-olds. This is a truly impressive work of art dating back to the second half of the 1930s, based on drawings by Angelo Canevari and dedicated to the theme of flight. More precisely, they depict the myth of flight and the relationship between man and the conquest of the skies as interpreted by the Fascist regime. The mosaics are perhaps the most striking example of the ‘dissonant’ heritage of the city of Forlì – the ‘città del Duce’ rebuilt as a showcase for Fascism in the 1920s and 1930s, but a city awarded the ‘silver medal for its part in the Resistance (‘Medaglia d’argento al valor militare per attività partigiana’) and with a strong post-war tradition of antifascism. The mosaics have an undoubted artistic value alongside a cultural and historical value as an example of the propaganda of the Fascist regime.

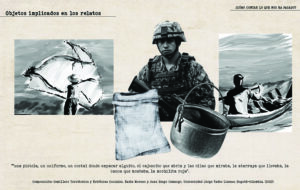

In his work Voices from Chernobyl (2015), in the chapter ‘Monologue on Why People Remember’, the Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich presents us with the testimony of the psychologist Piotr S., who asks, why do people remember? “Is it to restore truth? Justice? To free themselves and forget? Because they realise they have been part of a great event? Or because they seek some form of protection in the past?” This is the account of an ‘ordinary’ man, reflecting on one of the human tragedies that, beyond the intention to quantify it through the force of its death toll, impacts as profoundly as the Holocaust, the repression and disappearance of people during the civil-military dictatorship in Argentina, or the more than nine million people recognised as victims of the social and armed conflict in Colombia.

Mayki Gorosito is the Executive Director of the ESMA Museum and Site of Memory, a museum and memorial located within the former Navy Mechanics School of the Argentine Republic. During the civic-military dictatorship (1976–1983), it was the main Clandestine Centre for Detention, Torture, and Extermination, where approximately 5,000 people were abducted, tortured, and disappeared. As …

By Stéphane Michonneau, Paris-Est Créteil University / CRHEC and Babeth Robert, Director of the Memory Centre of Oradour While working on the emblematic site of Oradour-sur-Glane, researchers involved in the ANR Ruines project explored the phenomenon of “martyred villages” found in several European countries, including Spain, Italy, Greece, and the Czech Republic. The term refers, …

The Gusen concentration camp began construction in December 1939 and officially opened on 25 May 1940, with the arrival of over 1,000 Polish prisoners. From the start, it was part of the SS’s plans for the economic exploitation of the granite quarries in the region through the forced labour of concentration camp prisoners. The camp held a special position within the system of concentration camps named after its main camp, Mauthausen, which included over 40 subcamps. More than a subcamp, Gusen was considered a twin camp to Mauthausen.

By Maria Sierra, Professor of Contemporary History, University of Seville “We do not need a memory that shies away from the confrontation between victims and executioners, that eases consciences. We need a memory that walks through the carriages, that stands on the ramp, that sees the faces, that hears the screams”, Ewald Hanstein, Auschwitz survivor …

By Anja Kožul, freelance journalist “…Did they kill the Roma, too?” The greatest ‘murder of truth’ about the Roma concerns their genocide in the Second World War. Thousands of books, hundreds of thousands of texts, and millions of articles have been written about this last great global catastrophe and the suffering of various peoples in …