By David González, European Observatory on Memories (EUROM)

“The Teacher Who Promised the Sea” is a Spanish-produced film directed by Patricia Font, starring Enric Auquer and Laia Costa in lead roles. This fictional feature is inspired by the true story of Antoni Benaiges, a Republican teacher from the Freinet pedagogical school, who was killed by a Falangist squad in July 1936.

The plot of “The Teacher Who Promised the Sea” unfolds along two timelines: the 1930s and a present set in 2010, marking the opening of the Pedraja Mass Grave in Burgos. Each timeline has its own protagonist: the teacher Antoni Benaiges in the past, and Ariadna, the great-granddaughter of a Francoist victim and granddaughter of one of Benaiges’ former students, in the present. The interplay between these timelines adds dynamism to the storyline, holding the viewer’s attention and lending significance to the film’s conclusion.

The story begins in the present with a phone call Ariadna receives, informing her that her elderly, senile grandfather, Carlos Ramírez, had started proceedings to locate his father, Bernardo, believed to be buried in a mass grave in Burgos. This is where Ariadna’s journey begins – a physical journey to the Pedraja Grave and an emotional one that, through the phases of her obsessive investigation, leads her to confront a traumatic family past of which she had no prior knowledge. It is a journey filled with both progress and setbacks, mirroring the broader process of recovering historical memory in Spain. The director of the archaeological excavation at the Pedraja Grave warns Ariadna about what she might encounter along the way: “Some people open their doors to us, inviting us to eat and sleep, while others won’t even look us in the eye”.

At the grave, a local elderly man approaches Ariadna to tell her that his former teacher, a Catalan named Antoni Benaiges, might be buried there. The elderly man, Emilio, was once a student of Benaiges at the school in Bañuelos de Bureba. Emilio plays a dual role in the story, appearing both as a young schoolboy and as a warm-hearted elderly man who helps with Ariadna’s investigation.

Antoni Benaiges was born in Mont-roig del Camp (Tarragona) in 1903. After graduating as a teacher, he consolidated his implementation of the Freinet method in his classes while teaching in Vilanova i la Geltrú. There, he crossed paths with Patricio Redondo, a libertarian-minded teacher and a strong proponent of this educational approach in Spain. After passing the civil service exam, Benaiges was appointed to Bañuelos de Bureba (Burgos) in 1934, where he taught until the end of his life.

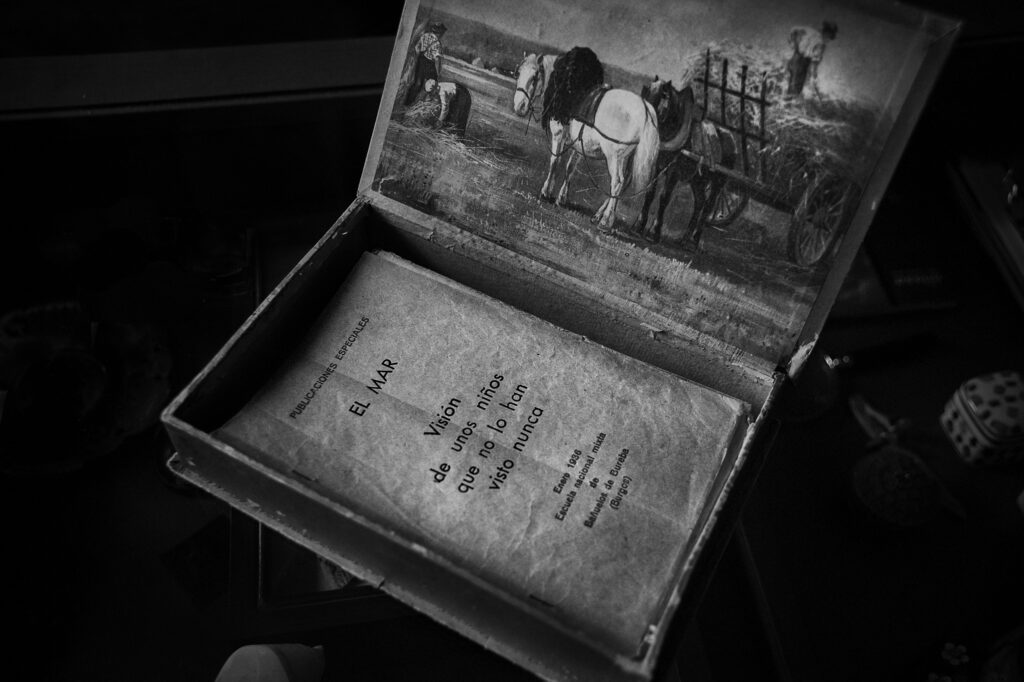

The story’s central moment comes with the discovery of a notebook titled “El Mar: visión de unos niños que no lo han visto nunca” (The Sea: A Vision of Children Who Have Never Seen It). The elderly Emilio accessed the notebook thanks to contact with Antoni Benaiges’s family, who had preserved some keepsakes of the teacher. The small notebook, created by Benaiges’s students, was printed on a press that the teacher himself had acquired through the cooperative of Freinet educators he belonged to. One of the pillars of the Freinet method was empowering children to create and narrate their own stories, which was made possible through the use of a printing press and the autonomous, cooperative work that children carried out around it. The children of Bañuelos de Bureba, having never seen the sea, inspired the notebook’s creation, prompting Antoni Benaiges to invite them to visit his hometown, Mont-roig de Camp (Tarragona), so they could see the sea for themselves. Antoni had to contend with the hesitations and opposition of some families, including those of Emilio and Josefina, the daughter of the mayor of Bañuelos de Bureba. Benaiges’s genuine persistence and his students’ excitement ultimately overcame these reservations, and he secured permission from all families to take the children to see the sea.

Tragically, the trip was never to happen. On 19 July 1936, amidst the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Falangist squads took control of the area and arrested Benaiges at the Casa del Pueblo in Briviesca. They tortured him, paraded him around, and destroyed the physical remnants of his pedagogical work, smashing the printing press and burning the notebooks. A few days later, he was killed, and to this day, the exact location of his remains is still unknown.

The film concludes with the elderly, frail Carlos Ramírez gazing towards the sea with a melancholic, contemplative expression as he listens to his granddaughter Ariadna’s tender words about his teacher and his father, Bernardo. The scene is poised between the resignation and suffering of the past and the modest but hopeful sense of reconciliation in the present.

“The Teacher Who Promised the Sea” brings to light issues that help viewers understand the educational processes experienced during the Spanish Second Republic (1931–1936/39). In a context where the Catholic Church held most of the resources and influence over the school system, and in a society facing illiteracy levels unworthy of a modern nation, the Republican educational reform of those years aimed to tackle this systemic backwardness, and would become a major target for Francoist repression. The secular teachers who worked during this period were, depending on the case, purged, detained, and even tortured and murdered. Such was the fate of Antoni Benaiges, who happened to be in Briviesca (Burgos) on that fateful 19th of July 1936, still preparing the children’s trip. If not for this, he would likely have been on holiday at his family home in Mont-roig del Camp (Tarragona).

“The Teacher Who Promised the Sea” skilfully uses the resources of audiovisual language to establish a fluid dialogue between different ways of approaching the past. It speaks to us of history—a finite, bygone past. It speaks of the unrestrained violence and political, social, and moral repression that took place in Francoist Spain following the coup of July 1936. But it also speaks of memory, of how this past echoes in the present, weighing on victims whose redress faces political, social, bureaucratic, and administrative obstacles. The identification and dignification of victims buried in thousands of mass graves across Spain has been one of the primary struggles of the memorialist movement in Spain since the beginning of the 21st century.

The revival and recovery of Antoni Benaiges’s memory has been made possible by the work of numerous individuals, particularly the photographer and documentarian Sergi Bernal, who has led efforts to uncover the story of this teacher. Bernal participated as a photographer in an exhumation at the Pedraja mass grave in August 2010, attending independently to document the process. On his way back to Barcelona, he received a call informing him that a local man had come to the grave, stating that a Catalan teacher who had taught in Bañuelos de Bureba might be buried there. This revelation led Bernal to unravel a story that would bring him deeply in touch with the memory of Antoni Benaiges. Bernal learned that Patricio Redondo, another Freinet teacher, had gone into exile in Mexico, where he continued to teach using the Freinet method, and he connected with Benaiges’ family, who had kept all the notebooks Benaiges had printed at the school in Bañuelos de Bureba.

Bernal’s connection to Benaiges activated one of those mechanisms that moves memory from a dormant, passive state to one that is alive and active. In the effort to reclaim the memory of many victims in the region, the forgotten story of this young, idealistic teacher emerged—his legacy still remembered in 2010 by those who had once been his students at the Bañuelos de Bureba school. The story of the promise of the sea, linked to the notebook “The Sea: A Vision of Children Who Have Never Seen It”, deeply moved Bernal, who became unwavering in his commitment to research and share Benaiges’s story. The scene in which Bernal received the call about the possible presence of a Catalan teacher in the Pedraja grave is recreated in the film through the characters of Emilio and Ariadna. Emilio, in turn, seems to be inspired by Eladio Diez, an elderly man from Bañuelos de Bureba and former student of Benaiges. Eladio, whose family preserved the few notebooks that had survived the July 1936 burnings, collaborated with Bernal by providing materials and sharing his invaluable testimony.Since the rediscovery of Benaiges’s memory in 2010, his story has left a profound mark and has been told through various formats, including literary essays, theatre, and previous audiovisual works leading up to “The Teacher Who Promised the Sea”. The film by Patricia Font has been well received in several countries, such as Italy, Taiwan, and Australia, and has become another piece in the activation of a living, useful memory with the power to impact the present. One touching example of the vitality of this memory process could be seen in the summer of 2024, when the Benaiges School Association, founded in Bañuelos de Bureba to preserve the teacher’s legacy, promoted the “Benaiges Mission” initiative alongside other organisations. This project supports a summer camp in which some thirty children aged 8 to 13, from disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Granada and Madrid, travel from Bañuelos de Bureba to Mont-roig del Camp to experience the sea. What better way to honour the memory of Benaiges and his students than to fulfil the dream those children couldn’t realise in 1936.