Vanesa Garbero

Sociologist, National Council for Scientific and Technical Research of Argentina

The collective book To Die in Madrid (1939-1944). The Mass Executions of Franco’s Regime in the Capital City, edited by Fernando Hernández Holgado and Tomás Montero Aparicio, fulfills the double role of being a book-memorial and a historiographic work that explains the repression suffered by Madrid after its occupation by the rebels, focusing on the mass executions that took place there. It is a book written during the first months of the pandemic produced by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which acquires its full dimension in relation to the memorial dynamics that unfold in the Spanish capital, and which make it hostile territory to the public markings that raise visibility of, and grant recognition for, the victims of Franco’s regime.

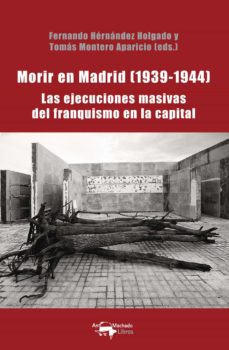

The image that presides over the book portrays the trampling of the monument projected in the Almudena Cemetery in memory of the people executed in the city of Madrid in the 1939-1944 period. Due to the decision taken by Mayor Martinez-Almeida of the People’s Party (2019-2023), the three frames prepared to display the nearly three thousand names of the victims look empty, for the mayor considered that, with them, the monument was “sectarian” and contrary to “the spirit of the transition, of reconciliation”. In front of the walls without names and without history(histories), stands the sculpture created by artist Fernando Sánchez Castillo: eight oak trees, metal replicas of the natural trees that were uprooted, stripped of their leaves, their branches cut off, their roots exposed to the air, lying on the ground.

As a counterpart to the action that sought to once again condemn the victims to oblivion, the authors dedicate a large part of the book pages for the inscription, one by one, of the names and some basic information about the 2,936 people executed in the capital city of Madrid in the postwar period. This is the revised version of the list drawn up by a team of historians led by Hernández Holgado and commissioned by the now defunct Office of Human Rights and Memory of the municipal corporation headed by Manuela Carmena (“Más Madrid” Party, 2015-2019), with the ultimate goal of building the aforementioned memorial monument. Unlike the pioneering work of Núñez Díaz-Balart and Rojas Friend in 1997, the team supervised by Hernández Holgado not only had access to the burial orders and burial books from 1939 to 1944, on file in the necropolis, but also to the burial records preserved between 1942 and 1944 that had not been consulted so far. In addition, the team had the list that since 2004 the group of relatives and friends of the victims of Franco’s regime in Madrid “Memoria y Libertad” has been updating and completing. The result of this research added 270 names to the first list compiled by Mirta Núñez Díaz-Balart and Antonio Rojas (1997), corrected existing errors and collected more information on the victims.

The book is completed with seven historiographic studies that address the different aspects related to the problem and an essay by the artist in charge of the sculpture. Consequently, Hernández Holgado reconstructs the microhistory of the old East Cemetery during the early postwar years in its double use as a “place of memory” and tribute to the victors and martyrs in the narrative of the New Spanish State, and as a site for the summary, mass, mostly nocturnal, almost clandestine executions of the defeated. His writing sets the context of the event and outlines the methodology used in the compilation of the list of the executed people. Montero Aparicio describes the meticulous and handcrafted research undertaken by the “Memoria y Libertad” collective on the list of people executed in the post-war period in Madrid, while at the same time he highlights the work of reconstruction of the life stories that each name entails. Vega Sombría addresses the persecution of, and the exercise of violence on, the defeated and focuses on the deaths in the first moments of the occupation that were not filed in the official records. Oviedo Silva points to the diversity that the list of victims involves and deals with those executed for “non-political” reasons. Pérez-Olivares tackles the legal construction of guilt in the summary emergency procedures that were needed for the executions and the civilian collaboration in the control which was functional for the regime. García-Funes analyzes the controversy surrounding the creation of the memorial monument in the cemetery, the reasons for its being brought to a standstill and the dismantling of the plaques with the names. Finally, Jiménez Herrera historicizes the origin and use of the words “checa” and “chequistas” in the Spanish Civil War and in the narrative of Franco’s propaganda, which are now being used again by right wing groups and mainstream media outlets in Madrid as an argument for requesting that all names be removed from the monument.

Overall, the research work undertaken by the authors evokes the “burial gesture” developed by Michel de Certeau and taken up by Paul Ricœur (2010). Historiographic writing in the manner of a burial rite “exorcises death by introducing it into discourse” and “allows society to situate itself by giving itself a past in language” (de Certeau quoted by Ricœur, 2010: 474). The Town Hall of Madrid must do its part now: to condemn the dictatorship and implement policies of memory, recognition and reparation to the victims of Franco’s regime. Thus, engraving their names on the memorial monument located in the old East Cemetery, a demand that relatives and memorialist groups have been expressing for almost twenty years, would be an inestimable first step.

References

Núñez Díaz-Balart, Mirta y Rojas Friend, Antonio. 1997. Consejo de guerra. Los fusilamientos en el Madrid de la posguerra (1939-1945). Madrid: Compañía Literaria.Ricœur, Paul. 2010. La memoria, la historia, el olvido. Buenos Aires: FCE.