Celeste Muñoz

Ph.D., University of Barcelona

GESA-Grup d’Estudis de les Societats Africanes

The Online Memories project and new social media narratives

On 26 March 2019, the Barcelona city government installed an upright historical marker in front of the local headquarters of the National Police in the centrally located thoroughfare of Via Laietana. The gesture was all but a symbolic act of remembrance that might have gone unnoticed except for the media firestorm that it touched off on social media. The reason: it was a troubling reminder of torture. The standing marker was installed by the Barcelona city government as a way to restore society’s remembrance of the Francoist dictatorship, pinpointing and identifying a place that is recalled even today for the brutality inflicted on myriad citizens by the regime’s political police. Of course, the reactions were varied and conflicting. Broadly speaking, studies of the collective public memory of our past may well focus on the processes of contestation surrounding the historical marker, which has suffered a slew of attacks while the police look on passively, almost in complicity. Such an analysis is doubtless very relevant. What interests us here, however, is to analyse and chart the spontaneous remembrance emerging on social media, which undoubtedly offers a genuine example of the conflict over memory. The “casus belli” of the conflict was a controversial tweet posted by then city councillor Carina Mejías, who criticised the marker as an “offense” against the police. Her statements were quickly met with responses from others on the platform. Soon more than 7,000 tweets had been posted with the hashtag #CuentaseloAMejias, reflecting hundreds of personal accounts of torture suffered at first hand or by family members during and after the Francoist dictatorship.

This was one of the first online phenomena analysed by the Online Memories project, which was sponsored by the European Observatory on Memories in 2019 with the primary aim of collecting European narratives and online debates over commemorations and holidays in the EU context. Clearly, the technological shift instigated in the nineteen-nineties and the new forms of political participation through social media arising in the twenty-first century have transformed the past decade, consolidating social media spaces since 2010 as lively structures with a major potential to have an impact on election campaigns and social mobilisations, to name but a few examples. However, relatively little attention has been given to the capacity of the various agents in these spaces to generate new discourses that can also serve as political weapons in the context of EU commemorations (as shall be seen in the analysis of Europe Day). This study focuses not only on the narratives themselves, but also on identifying the countries where the commemorations have had a greater or lesser impact online and on making comparisons of the year-on-year results for the same holidays. The principal challenge, however, involves the methodology – or to put it better, the creation of a new methodology.

In the field of history and in studies of historical memory, our familiarity with the use of procedures for online data mining is still limited. This is a shortcoming that calls for attention in the training given within the disciplines in question, because the internet of today amounts to the archives of tomorrow – and tomorrow is clearly here now. In order to prepare future biographies, the public profiles on social media will obviously provide crucial information; today’s political conflicts and processes, such as Brexit or the Covid-19 crisis, have an online footprint that contains key data for any future historical reconstruction and analysis. The field of historical memory is not – nor should it be – apart or immune from this reality. Teamwork among professionals trained in the field of new technologies is vital to formulating the new methodologies that are required. For the present study, the collaboration of Dr. Mari Luz Congosto has proved crucial[1]. Dr. Congosto has taken charge of collecting and processing the metadata used in the analysis and training the researchers on the project team in order to ensure that the complex intricacies of the resulting charts are easy to understand. Interdisciplinary work is fundamental to the pursuit of any research that currently lacks methodologies because it is emerging in nature.

In summary, the team’s methodology makes use specifically of the trending topics and key words (without hashtag) that are associated with a commemoration. Generally, searches of this type tend to limit the linguistic field, but not the geographical field. As a result, the aim throughout the project has been to progressively expand the language possibilities in the sampling. This has enabled the team to identify a growing number of new communities by language use and increasingly include voices from Eastern Europe. This approach, together with the establishment of time bands for tweets (primarily in order to discard information from North and South America), has enabled us to define affinity communities based on the interactions of users and the similarity of their tweets [2]. These affinity communities are the units that structure the analysis. Lastly, the need to establish a sociological profile of Twitter users has become increasingly important, with its inclusiveness and employment data providing another key plank in formulating the methodology and understanding the content.

The sociological profile of Twitter users

First, it is necessary to bear in mind that Twitter has a “bubble” effect. That is, many of the phenomena that happen on the platform are of little importance elsewhere. By contrast, some phenomena go viral, do have an impact on public opinion and can even generate so-called “fake news”, which has found a ready breeding ground on Twitter. The aim here is not to determine the reason why one debate is marginalised to a mere online existence while another transcends it. Rather, it is to take into account that the population substrata that engage in their creation are very specific. To this end, it is crucial to identify the substrata in order to establish any patterns (by gender, age, country, etc.). This undertaking is hard because Twitter only supplies very partial information and academic studies at present are very local and limited. However, it is possible to lay out some of the information that must be taken into account.

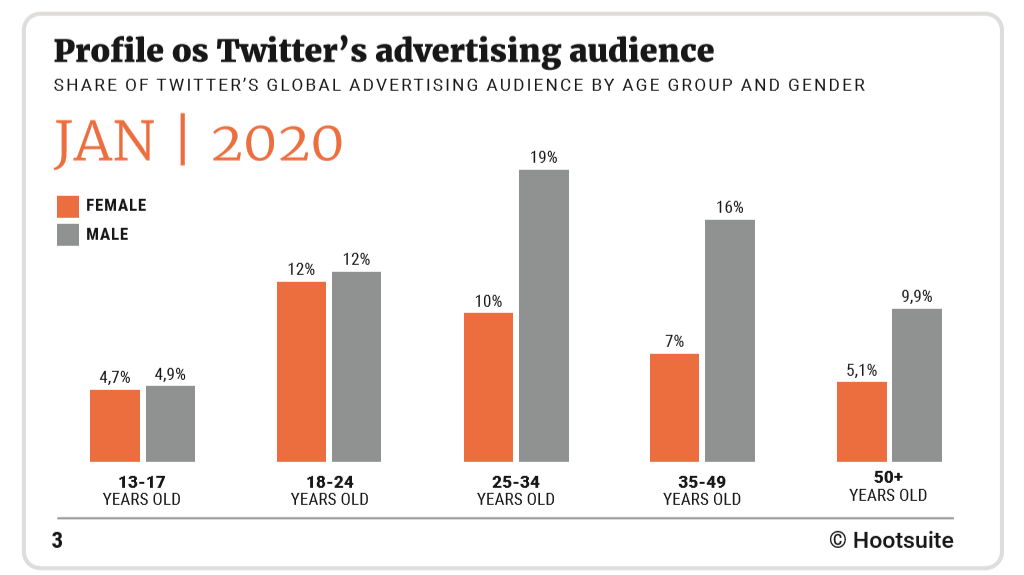

In 2018, 21.8% of Twitter users accessed the platform’s content from Europe. To be exact, 14.2% did so from Western Europe and 7.6% did so from Central and Eastern Europe. This represents 56.5 million Europeans in total. While the figure is not massive, it is nonetheless fairly representative. Based on the overall figures provided by Twitter, we also know that the platform is predominantly male (66%) and young (53.6% of users are between 18 and 34 years of age); users access the platform primarily with their mobile telephones; they live in urban areas; they have a high technological profile; and they have gone to university. Also, unlike other social media like Facebook, most users who access Twitter do so in search of information (56%), making it a politicisation space of major impact. Lastly, at the European level, the platform’s popularity varies by country. For example, the United Kingdom (17.1 million) and Spain (4.1 million) rank as the European countries with the highest activity on Twitter, together accounting for more than a third of the continent’s profiles. By contrast, Germany ranks as the European country with the lowest activity on Twitter.

Commemorations

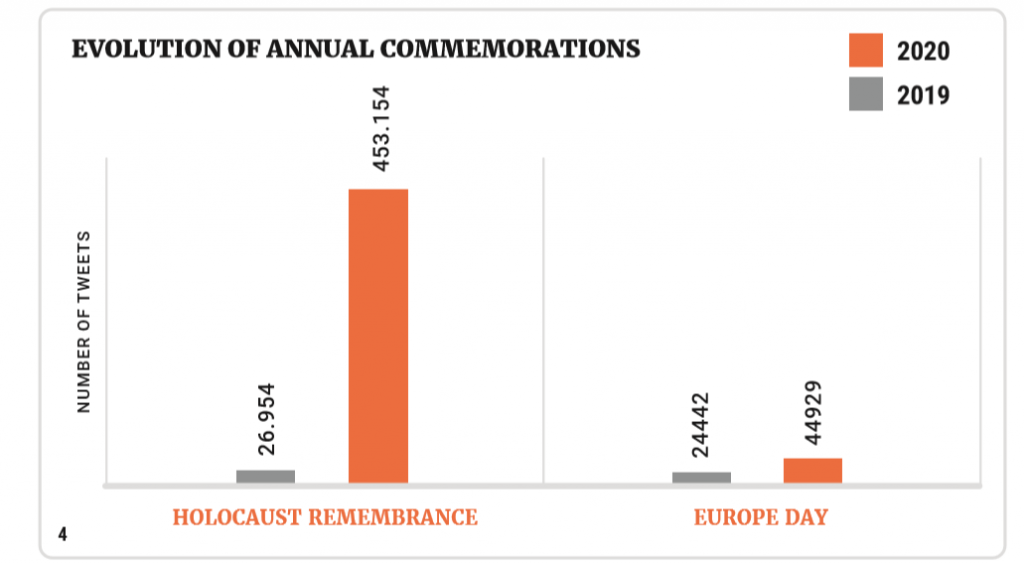

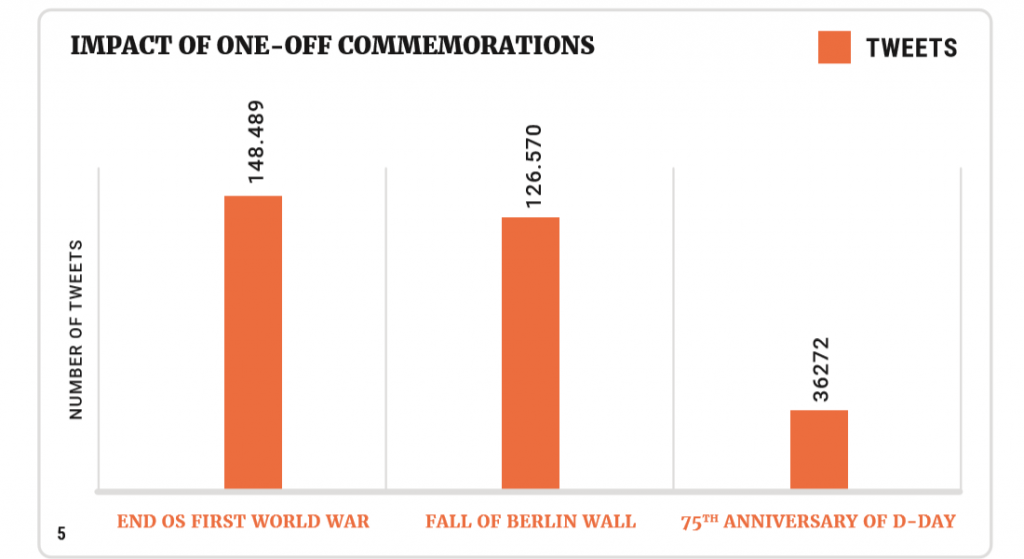

The project has examined a wide range of commemorative holidays and related phenomena. The commemorations are sometimes one-off events, such as the centenary of the end of the First World War or the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. These events cannot be tracked systematically, because they are limited to specific anniversaries. By contrast, institutionalised commemorations such as Europe Day, Holocaust Remembrance Day and Black Ribbon Day (in remembrance of the victims of totalitarian regimes) do leave an annual trail so that their evolution can be tracked over time. To this end, the analysis combines both types of phenomenon, with their disparate impact in terms of the volume of information that they engender. [3]

For example, if we take Holocaust Remembrance Day or Europe Day as a benchmark, Twitter saw an increase both in interest and in impact from 2019 to 2020. Europe Day doubled in impact, while the impact of Holocaust Remembrance Day grew by a factor of twenty. In principle, the latter growth can be explained by the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, which prompted increased participation by EU institutions and the media. This generated much more content in 2020, which was replicated in greater participation by leading figures and subsequently by other users. The analysis has also shown how messages on current issues are repeatedly mixed with messages about the past, relating the hate of the Holocaust with Brexit or with the rise of the far right across Europe today, or relating Europe Day with the need to seek unity in the battle against the Covid-19 pandemic.

As for specific one-off commemorations, the analysis has shown that they tend to have a greater impact on the platform, generating a higher volume of information and more trending topics. This is almost certainly due to the relative newness of institutional events, which occupy more of the political agenda throughout the year and therefore generate a great deal of interest. As shown by Chart 2 below, the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 2019 and the centenary of the end of the First World War in 2018 had a high following. At the European level, however, the fall of the Berlin Wall generated much greater impact than any other event. By contrast, a greater volume of the tweets on the armistice of 1918 came from the Americas (identified by using time bands).

While all of the analyses will continue throughout 2020 and 2021, the results of greatest interest here concern Europe Day. This is the commemoration that will be used in the comparisons and the constant monitoring analysis in order to identify the political uses of the date and the various meanings that it is given on Twitter.

Europe Day

Europe Day, which is celebrated each year on 9 May to commemorate the 1950 Schuman Declaration, is a key date on the European calendar. Representing a foundational moment for the European Union, the date seeks to commemorate the collaboration and efforts undertaken to overcome the differences of the past and build a present together. The celebration of the date continues to have an increasing impact in the media, which could also explain the growth of its impact on Twitter from 2019 to 2020. However, there are no monocausal explanations. At the time of the celebration of Europe Day in 2020, the continent – and indeed the whole world – was in the midst of a widespread lockdown. The Covid-19 pandemic of 2020 and the ensuing large-scale quarantine have resulted in an unprecedented situation for most of the generations experiencing them, so it makes sense that their impact would be the focus of a large proportion of the debates. In addition, preliminary studies suggest that the pandemic and lockdown may well have fuelled increased use of the internet and social media as sources of information and communication [4], helping to drive the growth in content relating to Europe Day as well. Moreover, the Schuman Declaration celebrated its seventieth anniversary in 2020, which is another element to bear in mind when analysing any growth in the date’s celebration. Indeed, the hashtags #70Schuman and #Schuman70 were both very popular. [5]

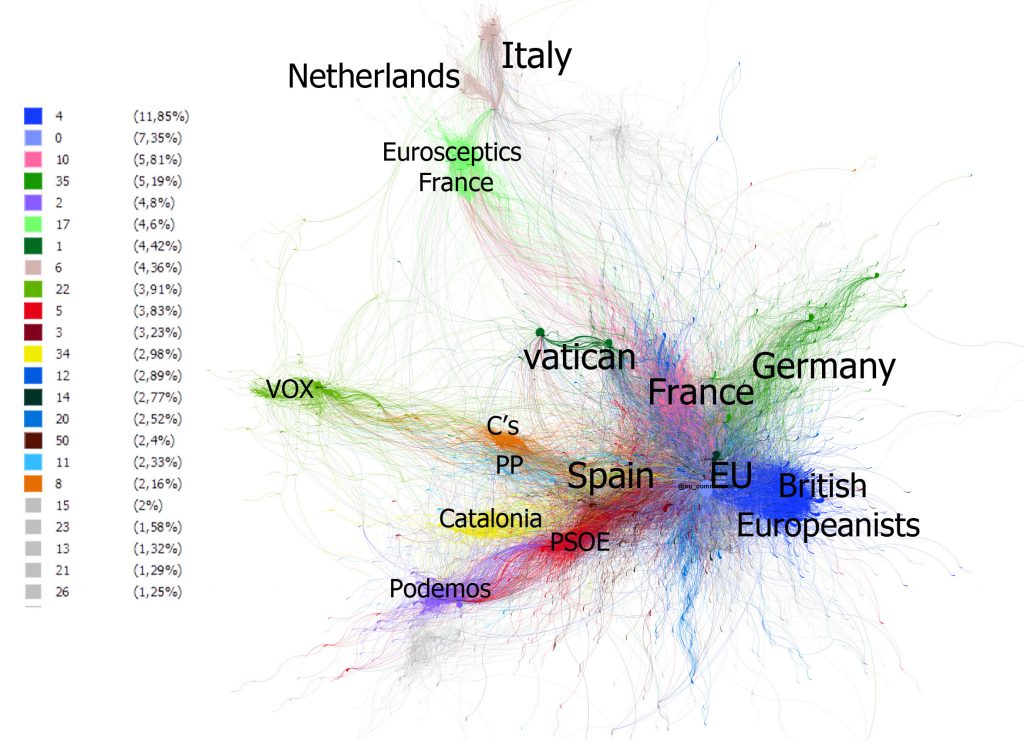

Focusing on the identification of communities linked to the celebration, it is important to highlight that there was a broad dispersion across isolated, very heterogeneous groups. Also, the language and ideological communities appear to be enormously fragmented between pro-Europeans and Eurosceptics.

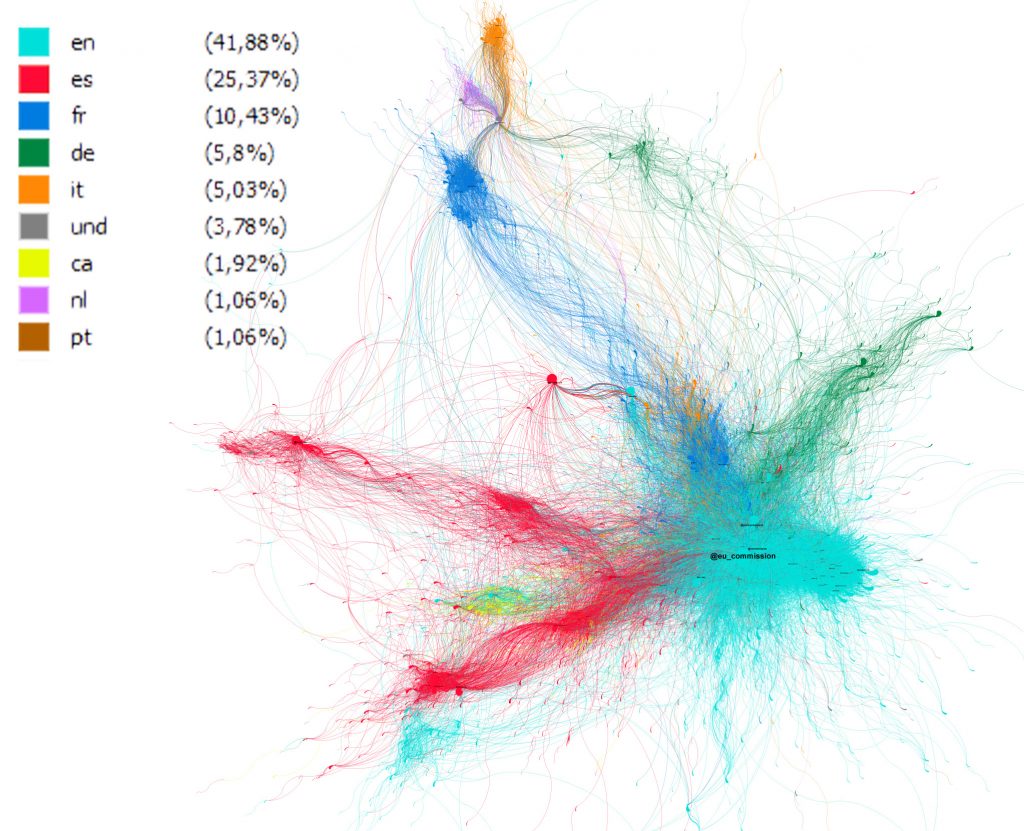

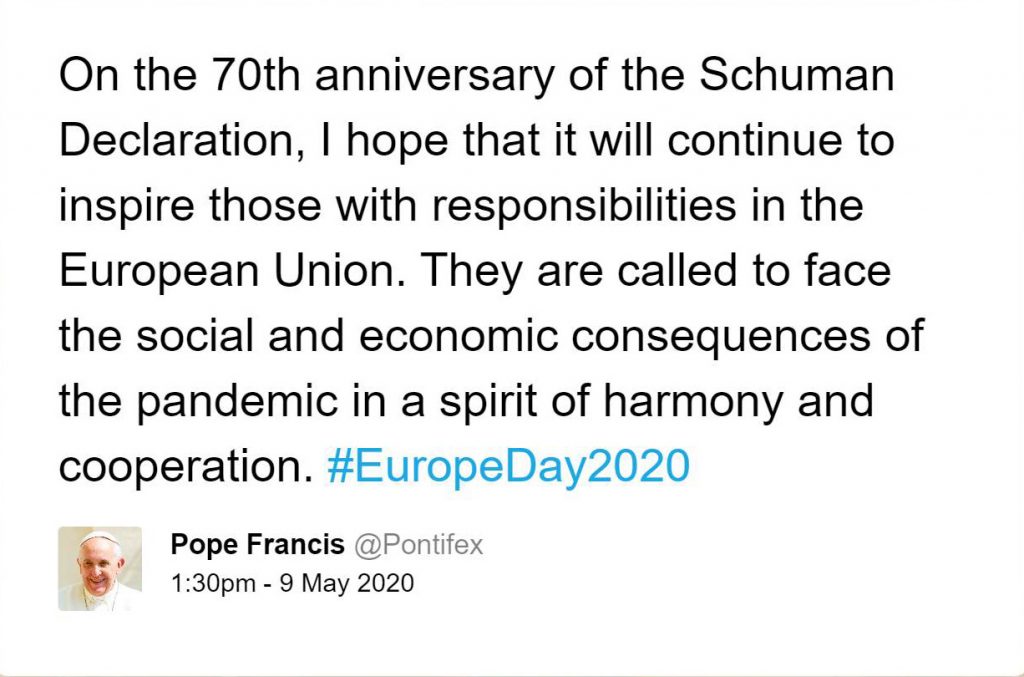

From the charts above, a comparison of the language communities – led by English [turquoise], followed by Spanish [red] and French [green] – shows that there has been a decline in linguistic diversity and a rise in the hegemony of English from 2019 to 2020. The second of the two charts provides much more large-scale information. In both charts (1 and 2), the communities on the upper-left side are related to Euroscepticism (whether French, Italian, Dutch or Spanish), while the communities on the lower-right side are pro-European (but to varying degrees, with a critical, albeit pro-European left that tends slightly toward the Euroscepticism pole at the bottom of the chart). In addition, the European Commission and its institutional offshoots appear as an important community (7.35%) in the middle of the chart at the epicentre of the phenomenon. The largest community overall is made up of British pro-Europeans (11.95%), who treated the celebration as an ideal opportunity to weigh in against Brexit. Indeed, the separation between the right and the left is apparent in the language communities within every state, marking an internal polarisation that appears to be sharper than for any other celebration. Lastly, if we compare the changing makeup of these communities between 2019 and 2020, we detect a sharp increase in Euroscepticism, especially in France and Italy. Also new in 2020 is the appearance of the Vatican (4.42%) through its account @pontifex, which acted as a bridge between Eurosceptics and pro-Europeans, given that the account interacted with both communities.

In the content analysis, the tweets with the greatest impact were once again put out by the European Commission in relation to the Schuman Declaration (3,900 retweets). The European Commission seized on the opportunity to call for political unity in the face of the Covid-19 crisis and it posted a video with messages of support from top EU leaders (830 retweets). In comparison with the previous year, it is also important to highlight that all of the posts from the account @UE_Commission had only 3,772 retweets in 2019, so we can observe an increase in the institution’s reach in social media. However, a discourse analysis of the conflict between pro-Europeans and Eurosceptics provides more clues than the EU’s own institutional context does, if we are to gain a better understanding of the new formulas of commemoration.

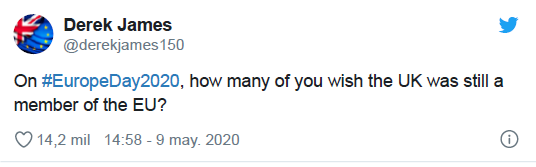

For example, we can observe a large pro-European community active in the United Kingdom, logically because of Brexit. In this group, the tweet with the greatest impact was posted by the political analyst Derek James (@derekjames150), who raised the question: “On #EuropeDay2020, how many of you wish the UK was still a member of the EU?”. However, leading political profiles, particularly members of the Labour Party, also played an important role, including David Lammy (@DavidLammy) and Richard Corbett (@RichardGCorbett). The overall thrust of the community, broadly speaking, was to challenge Brexit by means of discourses centred on the idea of fraternity. Noteworthy in this respect was the absence of a contrary discourse in the UK from Brexiteers, who are generally highly active in social media but were not very mobilised on the occasion in 2020. Turning to France’s pro-European community, the most popular tweet was posted by President Emmanuel Macron, who quoted President of the European Council Charles Michel and posted the official video mentioned earlier. Macron’s discursive line was to use the celebration to address the Covid-19 crisis by drawing a political parallel between the founding of the EU and its present healthcare challenge. By contrast, the tweet in Germany with the greatest impact and reach came from an activist called Daniel Mack (@danielmack), who posted a timeline with the continent’s periods of war and peace and ended with a statement that the European Union “ist das Beste, was uns passieren konnte” [“is the best thing that ever happened to us”]. Among Spain’s pro-European community, the most popular tweet was posted by the multifaceted communicator Javier Aroca, who recalled the EU’s early principles of solidarity, especially toward Germany, in a clear allusion to the current situation and the need to apply the same principles to Southern Europe in a context of systemic crises and need in those countries (@JavierArocaA: “En virtud del Acuerdo de Londres de 1953, se condonó, anuló o hubo una quita de la #deudaexterioralemana. Entre los condonantes estaba España y todos los Estados del sur de Europa. Feliz #DiadeEuropa. En particular a #Alemania” [“By virtue of the London Agreement of 1953, Germany’s external debts were forgiven. Those who agreed to write off the debts included Spain and all the nations of Southern Europe. Happy #DiadeEuropa. Especially to #Alemania”]). In the same vein, the Second Deputy Prime Minister Pablo Iglesias quoted Schuman and posted an excerpt of the declaration to argue on behalf of the same foundational organising principle. Indeed, most of the content posted by pro-European politicians in Spain harked back to those values of unity and solidarity in hopes that the solution to the new Covid-19 crisis, which has hit Spain particularly hard, would not be austerity and cuts to social spending as happened in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008. This line is similar to the one adopted by Pope Francis, who was especially active over the entire day.

In the case of the Eurosceptic community, we noted earlier that its presence on the platform has continued to grow, including tweets that could be categorised as hate crimes owing to their high degree of xenophobia. In France, where the phenomenon is particularly pronounced, the tweet with the greatest impact in 2020 came surprisingly from an anonymous profile with very few followers (345). The tweet introduced a survey on France’s membership in the EU (the result was that 88% of respondents voted for France’s departure). Along similar lines was a tweet posted by the politician Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (@duponaignant), who is a founder of the right-wing populist party Debout la France (see image below). The profile of the popular influencer Kelly Betesh, who has over 15 million followers, also had a major impact on the day through her posting of a photo in which she wrapped herself in the French flag as a symbol of her rejection of Europe Day. Other examples of Euroscepticism on Twitter appear in Italy and the Netherlands. In these communities, the tweet with the greatest impact came from the account @Jeroen99271706, which posted an image of the EU flag being set on fire in protest. In this respect, it is important to underscore that most of the tweets from the Eurosceptic community in Italy came from the political milieu of the Lega Party on the right. In the case of the Netherlands, the politician Geert Wilders (@geertwilderspvv), leader of the far-right PVV Party, went viral with the post of an explicit photo under the slogan “Nexit” in a clear allusion to Brexit. Lastly, in Spain, the far-right Vox Party and its followers were the main sources of Eurosceptic content, posting tweets that made reference to national sovereignty and the fight against illegal immigration.

To conclude the content analysis on Europe Day, it is also necessary to look at the tweets that could be characterised as Eurocritical, an area that lies at one end of the pro-European group and tilts slightly towards the Eurosceptic community but is not part of it. Unlike the Eurosceptics, Eurocritical sectors are found mostly within the parliamentary left, which does not support a break with the European Community, but does call for democratising reform. One example would be a tweet from the Euro MP Erik Marquardt of the Greens/EFA Alliance, who criticised the EU states for being “more concerned with the next elections than with the next generations”. Along the same lines was a tweet from Sawsan Chebli of Germany’s SPD Party, who seized on Europe Day to criticise the EU’s immigration policies and recall the refugees housed in the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos. These spaces were also characterised by humour and the use of memes. A popular tweet in this vein was posted by Ulrike Guérot (@ulrikeguerot), a founder of the EU reform movement called European Democracy (see image below). Likewise, in Spain, a cartoonist at the satirical magazine @eljueves resorted to humour in a tweet that enjoyed a fairly wide distribution on the day.

Conclusions

After laying out the overall project and the specific analysis of Europe Day, it is necessary to offer a few final reflections that are in no way meant to be definitive. The Online Memories project will continue to provide much more information in order to carry out much more thorough and rigorous analyses. At present, however, it is necessary to recognise the usefulness and validity of the present paper. First, this is because of the significance of the narratives and phenomena that it examines. Despite their lack of any physical materiality such as that provided by the completion of commemorative monuments or heritage initiatives, they nonetheless constitute new formulas of remembering in the present and the future. Second and closely linked to the first point, the project is significant because of its methodological work, which has few precedents. This work furthers the consolidation of the “digital social sciences”. Along the same lines, it will also be important to work through any ethical dilemmas that may arise, together with any case law established by each state to punish hate crimes on social media (which are sometimes a double-edge weapon in that they politically limit the freedom of expression and atomise dissent or opposition). Social media are one of the political battlefields of the twenty-first century. As a result, their usefulness as a source is fundamental. Third and last, the present study is significant because of the results themselves. By analysing Europe Day, it has been possible to identify the countries where the date’s commemoration is more deeply entrenched and those where it is almost non-existent; detect the remembrance of Schuman and his declaration in the present (in interpretations that are also conditioned by the present); learn which ideological communities reach beyond the constraints of language; ascertain the rise of Euroscepticism, its connections and its methods of influence; rapidly spot the impact of Covid-19 on access to the internet and on political discourse (in nascent form); and ultimately, gain a continental retrospective view through the analysis of a vast amount of information.

Footnotes

[1] Dr. Congosto is assistant professor in the Department of Telematics Engineering at Carlos III University in Madrid.

[2] At a technical level, the information has been collected by combining the methods of web scraping and T-hoarder (streaming API).

[3] The analysis has also examined other dates not included in these figures, such as Black Ribbon Day (in remembrance of the victims of totalitarian regimes), the Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day and the anniversary of the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic (14 April).

[4 ] See bibliography.

[5] By choice, the sampling does not include hashtags or words that refer to the date of 9 May, because it also the official date of the celebration of Victory Day in Moscow and the inclusion of such information might have distorted the results.

References

Online memories (first report): https://europeanmemories.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ONLINE-MEMORIES-FIRST-REPORT.pdf

Online memories (second report): https://europeanmemories.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ONLINE-MEMORIES-SECOND-REPORT.pdf

Online memories (third report): https://europeanmemories.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/OM-Third-Report-Web.pdf

KATZ, MARTÍN & JUNG, 2020. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3600829.

Hootsuite portal: https://hootsuite.com/es/twitter