Matilde Eiroa

Mari Luz Congosto

Universidad Carlos III de Madrid –HISMEDI Project

From black and white…

Forty-four years passed between the interment of Franco on 23 November 1975 and his exhumation on 24 October 2019. In Spanish society, a range of feelings have been expressed about the final location of the person who was dictator for four long decades. His death and burial in the Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen) had a strong impact in the media and in society that was almost paralysing. This was due more to the political consequences Franco’s death would have than to the formal procedure of his funeral. The ceremony within the basilica, which culminated with the placing of a slab engraved with his name and the obligatory protocol, was accompanied outside by Falangists, traditionalists, ex-prisoners, provisional second lieutenants, Legionnaire knights, brotherhoods of fighters, Portuguese Viriatos and members of the Portuguese secret police (PIDE), Romanian iron guards, Croatians, Italian fascists and German neo-Nazis, in a multicolour landscape of blue, black and brown shirts adorned with the medals of Mussolini, Hitler, Salazar and Franco. The monument erected under the direction of Franco with the labour of Republican political prisoners already fulfilled the purpose for which it had been constructed. It housed the embalmed body of Francisco Franco, Caudillo de España por la Gracia de Dios (Leader of Spain, by the Grace of God), as he was called insistently by his entourage of hagiographers from 1939, the end of the Civil War.

After his death, the media put Franco’s portrait on the front page and special issues described the physical decline and last days of the elderly dictator. The perspective was one of irreparable loss. Franco was presented as hero, saviour of the fatherland, providential man, the best statesman, an exemplary head of household, the sentinel of the west – in reference to his position as anti-communist guardian – and other descriptions that compared him with historical figures such as Alexander the Great, Napoleon, Charles V, Cesar or Hercules.

The social reaction to this historical event was polarised. We cannot provide exact numbers of those who were glad and those who began heartfelt mourning. The opposition to the Franco regime, Republican exiles, the entire labour and student movement, and millions of other Spanish people celebrated the death with quiet festivities in homes and clandestine meeting places. For them, this was a moment of hope with the start of a period that, from their perspective, would inevitably lead to the establishment of the democracy. On the other side were groups that supported Francoism, such as owners of big businesses, bankers and the military, as well as broad sections of society that were comfortable under the regime. Uncertainty seemed to be the only feeling shared by both positions, as all were aware that a time of profound changes was coming. Images of long queues of people waiting to file past the body show the interest in the figure of Franco, whether it was to pay respects or to ensure that he was dead, as many opponents stated. So the preliminary stages of the transition began, while Franco’s regime came to an end.

On the first anniversary of Franco’s death, some of the newspapers with the largest circulation in Spain put the dictator’s image on front pages tinged with nostalgia, mourning and evocation. Franco was presented as a man who had received a country at war – as if he had not contributed to the war’s outbreak – who had given it the longest period of peace in national history. The repressive policies he had used to achieve this were not explained. The Spanish king and queen, Don Juan Carlos I and Doña Sofía, presided over the official funeral service in the basilica of the Valle de los Caídos. Meanwhile, in the Plaza de Oriente in Madrid, where Franco had often summoned the masses when he needed what were known as “Actos de afirmación nacional” (acts of national affirmation), pro-Franco groups organised a gathering in homage to his memory. From then on, the Confederación Nacional de Excombatientes (National Confederation of Ex-Fighters, from Franco’s army) along with Franco’s family, members of the military, former ministers and well-known figures in the regime such as Blas Piñar or José Antonio Girón presided over commemorative ceremonies to cries of Franco, Franco, Franco, singing of the Spanish Falange’s anthem Cara al Sol, and some violent acts in streets and bars in which bystanders were made to do the Fascist salute or sing the aforementioned anthem. At the gathering of 1976, El País newspaper counted around a hundred thousand participants, a number that dropped to around six thousand in 1978, one thousand five hundred in 1989 and the same number again in 2000. Although the figures have fallen, these gatherings have not disappeared. They reflect the persistence of far-right groups in the Spanish political spectrum during the years of democracy.

The date of Franco’s death, which came to be known as 20-N, continued to be a key day for gatherings of the far right. The acts of homage to the dictator, which always culminated with a mass at the Valle de los Caídos and prayers in the military barracks, were transformed into a day of remembrance, but also a day of protest against the nascent democracy, lamentation for the disappearance of the dictator’s political legacy and criticism of the new historical phase that was beginning to open up cautiously. The gatherings always included a display of pro-Franco marketing, such as caps, kerchiefs, flags, medals, keyrings, calendars and framed photographs of Franco.

…to colour

With the arrival of the twenty-first century and the birth of the associative movement for the recovery of historical memory, the fate of the Valle de los Caídos was put on the discussion table. Franco was the only dictator whose remains had survived in a mausoleum in a democratic country. The mausoleum had been constructed to enshrine the values of the dictatorship and glorify Franco’s victory in the Civil War, the source of his legitimacy. He had died of old age, not killed in conflict, and his cadaver shared a burial place with the bodies of over thirty thousand people from the two armies that had fought in the war. The associations demanded an end to this painful situation in which victims were buried next to their main executioner. Political parties with parliamentary representation agreed to do something with the largest crypt in Europe. However, the decisions were postponed, especially during Mariano Rajoy’s term in office (2011-2018), as he rescinded the budget set aside for compliance with the Ley de Memoria Histórica (Historical Memory Law, 2007).

The new president of the government since June 2018, Pedro Sánchez, announced that one of his executive’s measures would be to exhume Franco from the Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen), to meet a democratic obligation that had been adopted years ago. In February 2019, an order was approved to carry out the exhumation and transfer of the general’s body to a place chosen by his family. However, Franco’s grandchildren appealed, and the courts suspended the order. Finally, on 24 September, the Supreme Court endorsed the exhumation of Franco and his interment in the Mingorrubio cemetery, close to the Palace of El Pardo, which had been his usual residence. A month later, on 24 October, the funereal procedure took place before the eyes of millions of spectators who watched this historical moment from their homes.

Beyond the parliamentary debates and discussions of politicians before the media, an intense controversy emerged on Twitter between people of varying ages and profiles. Under the hashtags #exhumaciónfranco (Franco exhumation), #elvallenosetoca (the valley shall remain) or #unboxing, opposing opinions were observed, as we will see below. From 31 March 2019, when the provisional suspension of the exhumation was in force, to 24 October, the date of its execution, we monitored the reaction on the internet. Over this period, activity, both for and against, depended on the progress of the events. On 4 June, when the Supreme Court paralysed the exhumation, the number of tweets reached 50,000 per day. On 24 September, when the same Court endorsed the exhumation, the number of daily tweets doubled. Finally, on 24 October, the day designated for the disinterment, the number of messages increased fivefold. In this last month, there was intense participation on Twitter about the preparations for the event, but also about Franco and his dictatorship.

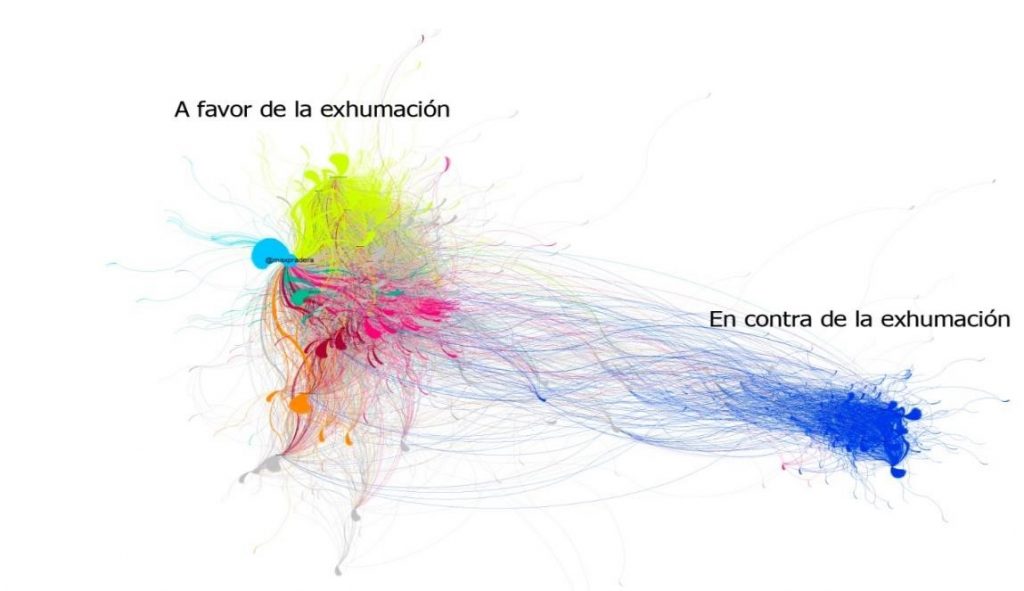

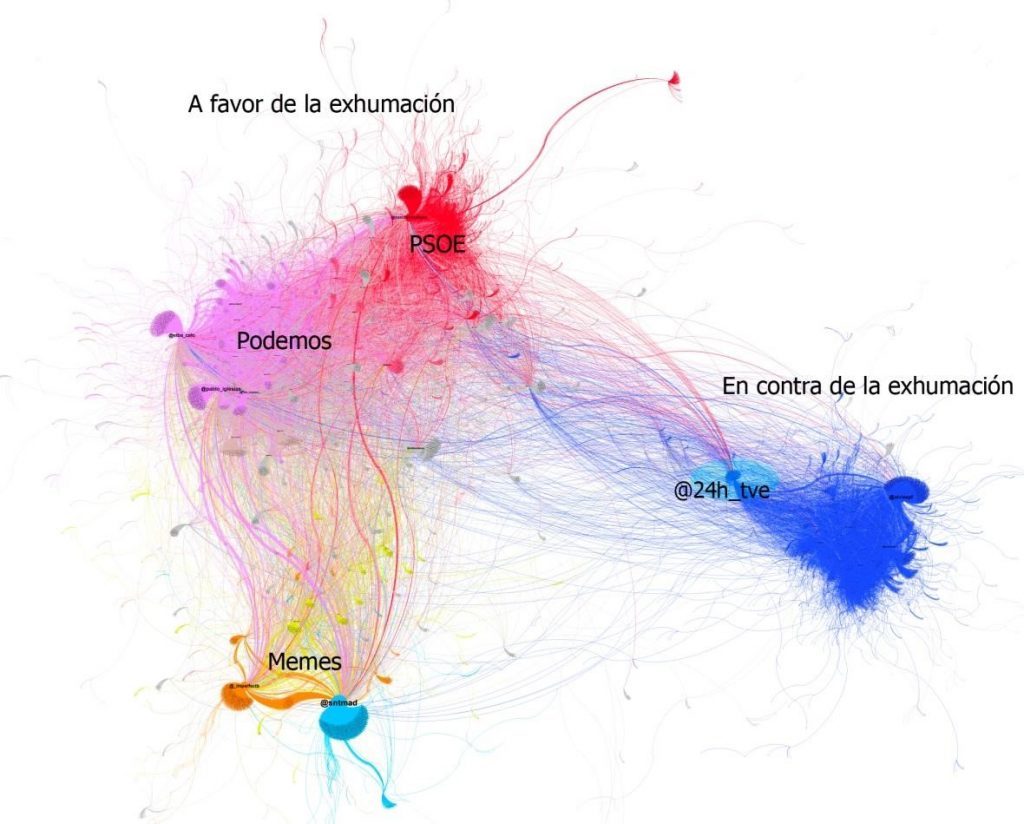

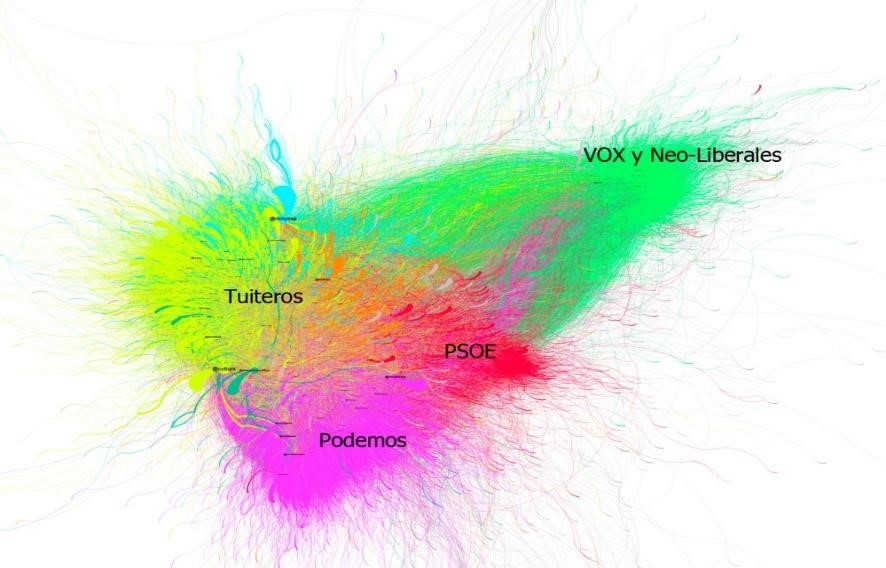

In the analysis of social networks, the social group against the exhumation, which identifies with right-wing and far right political parties, was found to have a strong, uniform structure of connection. In contrast, groups in favour were divided into subgroups around nuclei of associations for historical memory, left-wing political parties or people who wanted to express their opinion.

In the period between 22 and 26 October, the dates before and after the event, over a million tweets were posted. The division of opinions was not so radical because there was mass participation in which many users did not have a clear opinion, but their messages were widely shared. However, a clear separation can be seen between the far-right party VOX and its supporters compared to other groups.

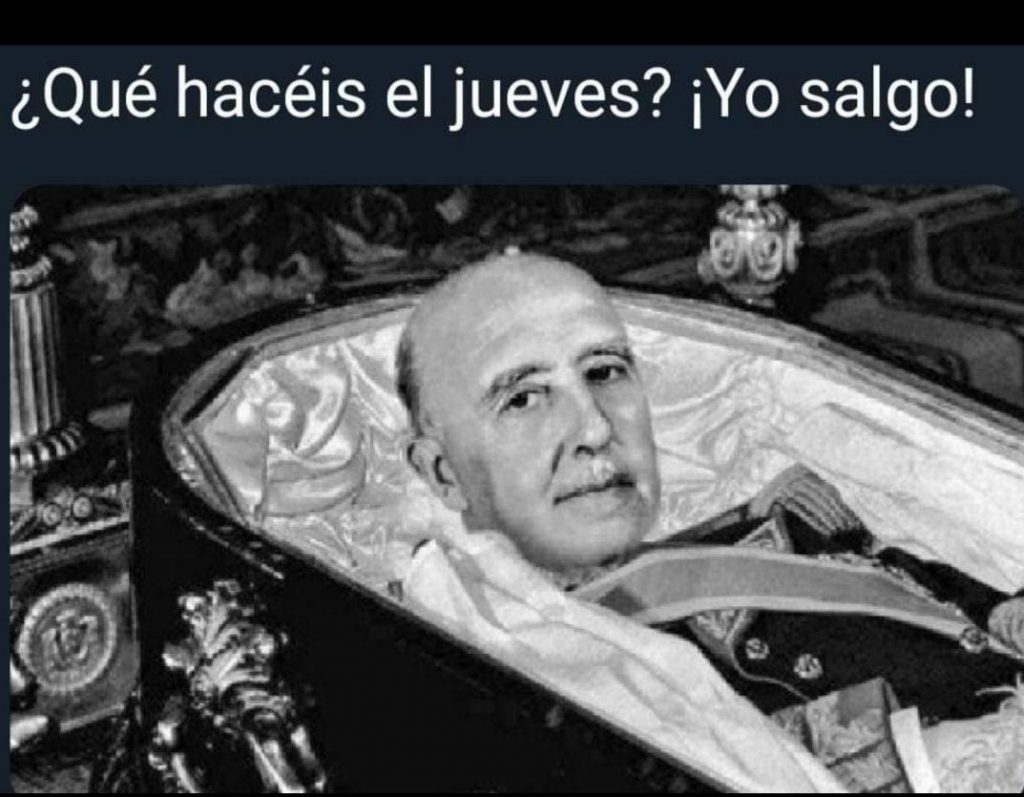

Between the Supreme Court’s ruling of suspension (4 June) and endorsement (24 September), the controversy was enriched by the appearance of a new actor: humour. On Twitter, sarcastic and ironic messages often circulate that ridicule all kinds of events and are sometimes on the limits of black humour. In the case of Franco’s exhumation, humour came from the social bloc in favour of taking him out of the Valle. The messages swept up many users who would not have participated in the discussion otherwise. Much of this humorous content was expressed in the form of memes, some trivialising the situation, others making fun of the dictator himself.

Regarding doubts about how the disinterment and reburial process would be carried out, various memes circulated that proposed solutions. One showed an image of the children from Steven Spielberg’s famous film E.T. (1982) transporting the dictator on their bicycle.

Another satirical post showed Franco’s old ally Adolf Hitler driving him out of the Valle in one of his majestic Mercedes Benz cars. So the Führer saved the Caudillo from a new difficulty.

One of the memes that circulated most on Twitter and WhatsApp groups referred to the fact that Franco’s removal from the Valle would take place on a Thursday, which is the day that many students start to go out for the weekend:

Translation: “What are you doing on Thursday? I’m going out!”

Source: https://cronicaglobal.elespanol.com/cronica-directo/curiosidades/franco-memes-exhumacion_286284_102.html

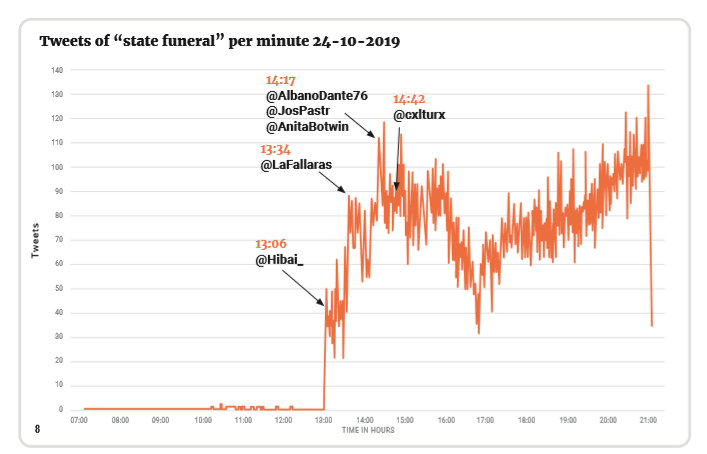

The historical event, which was eagerly awaited by the left-wing parties and the associative movement for historical memory, generated a lot of controversy about the exhumation protocol. On the day, the hashtag #Funeraldeestado (State funeral) trended. This term began to be used widely even before the start of the ceremony. At 1 p.m. on 24 October, its use shot up when some influential figures on the left picked it up, particularly individuals associated with the Unidas-Podemos party. However, others stated that they were against using this concept, as they argued that it should be applied to deserving governors, not to a dictator.

Outside the Valle, as at the time of Franco’s burial in November 1975, and in the surroundings of the Mingorrubio cemetery where the body was taken, several dozen members of the far-right and people nostalgic for the Franco regime congregated. They carried banners with messages supporting the dictator, in the style of the darkest years of the regime. Slogans such as Viva Franco (Long live Franco), Arriba España (Up with Spain), the Falange anthem Cara al Sol, the fascist salute, and the presence of Antonio Tejero, the Civil Guard policeman who led a coup attempt on 23 February 1981, were the elements adorning the interment in the new tomb. The Franco family, the Francisco Franco National Foundation, the Benedictine community that lives in the Valle, the Association for the Defence of the Valle de los Caídos and other neo-fascist groups are the collective that aims to pay tribute to and recover the general’s reputation.

A few days after this event had occurred, Twitter users dropped the topic. There was a slight upturn of 22,000 tweets on 19 November, the day before the anniversary of the dictator’s death.

Forty-four years after his demise, opinions about Franco have a very similar ideological map to that found in 1975, but with the addition of satire. Social networks have revealed clearly and comprehensively the public opinion about a decision that was considered necessary and urgent by much of Spanish society that is eager to close the past.