Henry Rousso

Senior researcher at the Institut d’Histoire du Temps Présent (CNRS, Paris)

Version reviewed and corrected by the author

For an extended reading check also: Rousso, Henry. Face au passé. Essais sur la mémoire contemporaine, Paris, Belin, 2016

The need to understand the past and provide a collective representation of history is anything but a recent phenomenon, nor is it strictly a European one. Nevertheless, something has changed in the last four or five decades regarding how contemporary societies deal with the past. The place of the past in the present, the kind of events which are the most commemorated, and the reasons why there are so many public investments in the field of history have progressively changed.

The most spectacular evolution has been the emergence of “memory” as a major political and moral value. This is now a new kind of human right promoted all over the world, far beyond the European scene where it was born in the 1970s. What was at stake during this period was not the remembering of the past in a general and traditional way, but a new approach specifically addressing the black spots in History. These forgotten or unwritten pages, beginning of course with the permanent and official remembrance of the Holocaust and the Nazi past as a whole, became a core element in the building of a European identity both before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Apologizing for past wrongdoings, recognizing the victims of collective traumas (including wars, dictatorships, and now even major accidents or natural catastrophes), and suing the perpetrators of genocides and other mass crimes progressively informed the political agendas of states, parties, and groups. The duty to remember and commemorate these aspects of the past became a major element in processes of democratization all around the world.

A commemoration should be not only a moment for remembering the past and paying tribute to the victims, but also a moment to reflect upon the commemoration itself– its achievements, its failures, and its evolution.

In a long-term perspective, the concept of “memory” is a recent evolution. It is likely part of a deeper phenomenon and an element of a new “regime of historicity”. This is a shift in the perception of time and the relationships between past, present, and future. Many historians and philosophers, i. e. François Hartog, suggest that the major change lies in the importance given to the present, the immediate satisfaction of needs, the inability to think about a remote future, and the trend to interpret the past through the lens of the present. This is what can be defined as “presentism” as opposed to a perception of time focusing on the future, which prevailed in the aftermath of the French Revolution until the 1970’s, when most political actions were either positively or adversely influenced by the idea of Progress, a dynamic movement towards a better world.

For my own purpose, this new “presentism” regime of historicity includes the rather recent idea that contemporary societies could and should act upon the past. Repairing history has become a fundamental motto of our generations. Remembrance as a social activity is no longer a practice limited to a minority of activist groups like victims or veterans’ associations as it still was the case before the “memory boom”. Today, the concept is implemented in public policies at a local, national, European, and international level. Its implementation involves a various range of stakeholders: international institutions and NGOs, central states and administrations, regional and local institutions, private and public players, and associations of all kinds. The act of collective remembrance also covers a wide range of fields, which I describe here by pointing their achievements and the problems they raised.

Researching

In the past decades, the “memory boom” has been clearly visible in historiography, and all the humanities or social sciences. Historians have changed their academic focus, and started to pay more attention to the perception of time as such. Following Foucault, Ricœur or Koselleck, philosophers paid more attention to the past as a representation and a social construction than studying the traditional philosophy of history. Psychologists have deeply invested the field of traumas and victimization. Nevertheless, one must pay attention to some possible problems associated with these approaches.

Though the concept of “collective memory” has been a major theoretical tool in analyzing the “present of the past” in the last two decades, it must not subsume other concepts which can help to describe the link between past and present. In order to understand the recent past and its lingering impact on society today, one must take into account the roles and the place of political traditions, social heritages, filiations, and anthropological invariants. Ultimately, the current concept of collective memory is too closely linked today to the psychological notion of trauma to provide the only possible framework for a collective representation of the past, especially since the traumas of the 20th century have begun to lose their original impact (at least at a collective level). In other words, “memory” cannot describe all the complexity of the presence of the past.

In the last two decades, for example, the historical works on the two World Wars have exhibited a paradoxical development. On the one hand, large investments by public agencies and foundations have allowed for the sophistication of research approaches, aided by the implementation of an impressive range of tools, methods, and concepts which have had an impact far beyond the world of specialists. On the other hand, there has been a growing parallel public preoccupation with these events, resulting in the use and even the creation of multiple sources of information by ordinary people: databases, websites, local researches, and genealogic works – a phenomenon known in North America as “public history”. Interestingly enough, the development of this new public history is clearly part of the above-mentioned memory boom. But at the same time, it raises a real challenge: while the “democratization” of historical knowledge can reap real progress in sensitizing the past, it can also allow all kinds of manipulations, fake history not to mention the Holocaust and other genocides deniers.

Teaching

Throughout Europe, teaching contemporary history became a challenge, sometimes a permanent battle, especially in primary and secondary schools. Though there have been important investments in programs and textbooks as well as in exploring the relevant methods to reach a young audience, there are still many controversies about how to teach historical traumas.

Do we need to evoke emotion in order to sensitize the children and students to these issues, especially regarding episodes for which they lack any direct link? If so, to what extent? What is the real impact on teenagers of the use – and sometimes the abuse – of the “Auschwitz trips” or similar initiatives? How do we fight against the unavoidable trivialization or the artificial effect of what has become a form of “catéchisme mémoriel”? Teaching vivid issues on the recent past doesn’t mean abandoning any form of critical view on the past.

Is the school a place where different memories have to be emphasized in order to respect each religious, ethnic and/or cultural minority, or is it capable of creating a feeling of shared history? If the latter is achievable, how do we create this feeling without imposing an artificial consensus?

One of the solutions adopted in French schools has been to teach some elements of the history of memory at the end of the secondary degree in order to explain that a given historical event may have several interpretations and meanings in respect to time, space, social groups, etc. In this sense, teaching the history and memory of WWII – or the Algerian War – encourages these students not to take a historical narrative for granted.

Commemorating

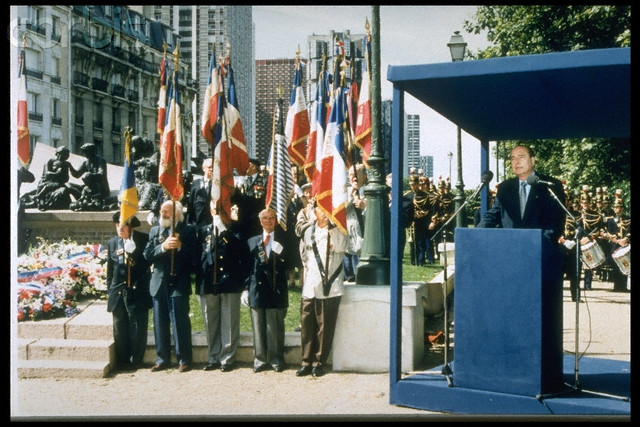

The number of commemorations has increased everywhere, and their nature has also profoundly changed, as we can see it in the appearance of “negative commemorations,” which occurs in many countries, including those where the past was once a traditional source of pride. In France, for the first time in the nation’s history, the government established in 1993 an official ceremony not to celebrate a victory or a national martyrdom but to remember the crimes committed by the State (the Vichy regime) against the Jews during the Holocaust (July 16th). Following this trend, too other negative commemorations have been implemented in 2006 and 2017 to commemorate the crimes committed throughout history against enslaved peoples.

At the European level, the negative commemorations have at times dwarfed “positive” ones: the recent transnational negative commemoration of the Holocaust on January 27 (established in 2000 by the Task force and in 2005 by the United Nations) has been much more popular and visible than the older Europe Day of May 9 (established in 1985,) which never substantially facilitated a forging of shared memory or history.

The challenge here is to find a balanced policy between a negative view of the past, which is necessary to avoid any oblivion about the crimes committed in the recent past, and a positive view, which has to be reinvented. An unbalanced policy can result in a kind of exasperation about the exclusive focus on the dark side of recent history, or in a counter movement to rehabilitate national heroes who are not consensual figures at the European level.

Law and justice

Practices that seemed rather exceptional in the 70s – like judging war criminals a long time after the facts –became afterwards a norm as we can see it in the belated trials in Germany, France, and Italy against former Nazis and collaborators. Simultaneously, the various policies of purges and lustrations launched after 1989 in Eastern European countries reinforced the idea that either the law or a judicial process could be major vectors for memory, even if the impact of the post-communist trials never had the same magnitude of the post-war trials against Nazism and Fascism.

Finding a good balance between the necessity to fight against “revisionists” trends or political oblivions, on the one hand, while respecting the freedom of speech and the freedom of research, in the other hand, is probably one of the most important challenges for a near future.

At the same time, there has been a growing trend to promote normative views of the past, even in countries where freedom of speech remains a strong tradition. In France, the “lois mémorielles” — laws that defend an official interpretation of a given historical episode (i.e. the Algerian War) or an official framework of criminal law (i.e. Western slavery as a crime against humanity), instigated tremendous polemics and intense activity amongst scholars and politicians. One can see a similar development at the European level: recently, the European Commission recommended that the EU members promulgate laws repressing all forms of denials of genocides or crimes against humanity, based on what has been done against the Holocaust deniers.

Such normative views of History are highly controversial. Striking a balance between the obligation to fight against “revisionists” trends or political oblivions while respecting the freedom of speech research might prove to be one of the most important challenges in the near future.

Klaus Barbie photo on the fake admission document in Bolivia on behalf of Klaus Altmann, made in Genoa by the Consulate of Bolivia in Italy | Public Domain

Jacques Vergès, French lawyer involved

in legal cases for high-profile defendants charged with terrorism or war crimes, including Nazi Klaus Barbie in 1987, terrorist Carlos the Jackal in 1994, and former Khmer Rouge head of state Khieu Samphan in 2008. He also famously defended Holocaust denier Roger Garaudy in 1998 | Source: Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (Flickr: Case 002 Initial Hearing) [CC BY-SA 2.0

Some reflections about the future of memory

In the recent past, public initiatives, under the initial pressures of civil societies, have played a major role in promoting research, commemorations, museums, policies of apology, trials, etc. In a near future, I believe that local authorities, private stakeholders and autonomous citizen organizations will all play a more active role for different reasons. At a local level, there is and will continue to be a strong economic interest to develop “dark tourism” as we can see it all over Europe (and elsewhere) in the building of new museums and memory sites. Moreover, local or private initiatives, even modest ones, will likely have more money to finance various projects than those of the central states that must prioritize crackdowns on colossal public debts.

The more the process of remembrance (mainly focusing on the Holocaust) has been considered as a “universal” issue, the more the central level (the states or the EU institutions as such) was involved. In the future, I ultimately believe that debates over the past will concern increasingly specific groups and diverse historical episodes. In turn, private institutions, organizations, associations or foundations of all kinds will play a heightened role in the rise of “public history.”

As a matter of fact, the future of remembrance will change because the model of “memorialization” which developed itself from the 70s on, mainly through the tremendous challenges of the Holocaust legacy, will change for at least two main reasons.

The first reason has been anticipated for a long time: the last witnesses of the Nazi era will disappear in the next decade. Their absence will dramatically change the narratives of the recent past. Historians, social scientists, film-makers, and designers working on these topics will have to work “alone”. Historical narratives, museums, and films will have to find new ways to represent the history of this tragic moment.

Though this will pose a major challenge, I don’t expect that we will have to cope with something like a gap between two different memorial regimes. Firstly, the relationships between survivors, researchers and politicians have been all but harmonious in the last decades. There have been many conflicts and controversies about the different ways to represent and transmit such an experience like the Holocaust. In this sense, the disappearance of witnesses won’t be the first challenge raised to Holocaust policies of remembrance. Secondly, we have now learned through the example of WWI Centenary that the absence of survivors can stimulate research for new documents, written testimonies, and new interpretations.

The second reason is directly related to the last. The remembrance of the Holocaust has played the role of a model, even a paradigm since the late 70’s, and it is now more or less a major element in the ongoing construction of a European identity, a situation that cannot remain unquestioned.

From the 1980s to the 1990s, most European countries undertook the largest collective anamnesis in recent history, leading to policies of apology and reparation, major trials, new commemorations, and a strong implementation of teaching and transmission, as mentioned above. Did this process ever come to an end? Did it achieve its goals? Is evaluation of its efficiency even possible? Looking at only one example, we can observe that the large investment in the remembrance of recent totalitarian experiences (like Nazism and Communism) has had a rather small impact on contemporary European politics; it didn’t prevent the rise of movements fuelled by xenophobic or racist ideas, whether we call them “populists” or “neo-fascists”.

With the case of France, the Front National rose parallel to the implementation of official policies of remembrance, and it reached its peak at quite the same time as when the French state, in the mid-90s, recognized its own responsibility in the Holocaust. Therefore, there remains an urgent question about the role played by recent so-called “policies of the past,” or “policies of history,” not only in a moral or ethical perspective, but also in terms of democratization.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, one could have believed that the same methods used to recognize and repair the crimes committed during the Holocaust could also be used to resolve other traumatic pasts, like those tainted by slavery, colonialism, and, above all, Communism. Twenty years later, this belief seems partly irrelevant. Specific concepts and practices of memorialization have been developed for dealing with the past in Eastern and Central Europe, raising new and specific challenges. There is the question of how balancing the legacy of two competitive totalitarian experiences. The conflict between policies of memory, which were supposed to improve human rights, have led to a rebirth of nationalist feelings. Last but not least, the shortcomings of the juridical systems, which has been a major force in shaping historical memory in Western Europe since 1945, failed to do the same in Eastern Europe.

Therefore, it is unlikely that the Holocaust paradigm will remain the only relevant one in the near future, nor it is likely that there will be a new paradigm comparable to that of the Holocaust. The model built for the Holocaust remembrance — important though it is due to the necessity to cope with an unprecedented experience – cannot just be copied. Moreover, coming to terms with the Communist legacy will also change the ways in which we narrate and remember European history in general, including in the Western part of the continent. The memories of other traumas will evolve into increasingly refined expressions, even if the Holocaust model may still serve as a reference. Even if the Communist experience was a pan-European one, and even if the magnitude of the crimes committed on its behalf were tremendously tragic, there is no sign that this collective experience could play the role played by the Holocaust legacy. There is no sign indicating that the Communist experience might be seen as “universal” as was the Holocaust one. Consequently, establishing a fundamental framing around communist experiences, in their varieties and complexities throughout both the East and West will prove to be one of the greatest challenges for the development of any European policy of remembrance in the following years.

In brief conclusion, I suggest that any activity in the field of remembrance should go beyond a moral perspective. It should instead provide a political vision by striving to understand how remembrance activities might concretely improve our democratic systems. It should also strive to generate new knowledge of the past itself, while simultaneously coping with its memorialization. Above all, one must contemplate the real purpose of a remembrance policy, that is sharing a common legacy of the past rather than centralizing its differences. Recently, there have been too many competitive forms of victimization, and not enough proactive efforts directed towards how these differences could and should be overpassed.

The choice presented to us is not easy, nor is the answer obvious. Should we insist again on the idea that remembering the Holocaust has a universal dimension despite the fact that this is all but consensual, or should we try to invent new means of remembering, which will take into account the diversification of historical experiences? In a certain sense, we should probably disconnect the question of memory and that of identity. The Holocaust doesn’t only concern the Jews just as slavery and colonialism doesn’t only concern ethnic minorities, nor it doesn’t concern only the European states. There are many other components that make up a social identity aside from the sharing of dark memories from traumatic pasts. And what is true for communities, is also true for nations, and, in the end, for the European Union.