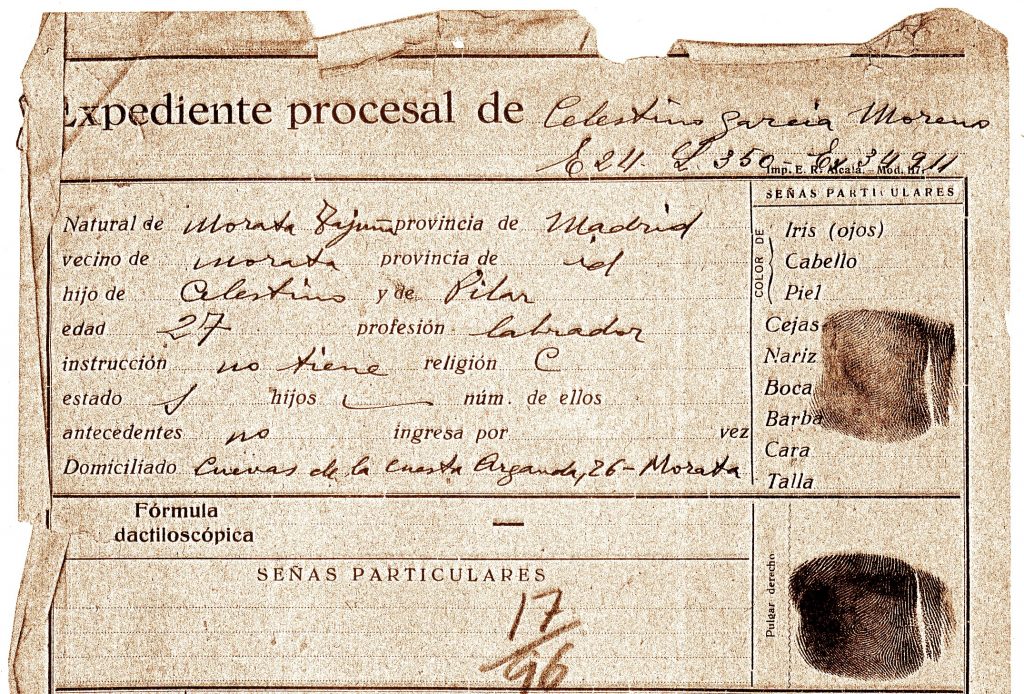

Picture: Detail of the penitentiary file of Celestino García Moreno, peasant of Morata de Tajuña, shot on June 14, 1939, in the walls of the East Madrid cemetery | quieneseran.blogspot

By Fernando Hernández Holgado, associate professor at the Department of Contemporary History of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid

A historical note

Madrid was one of the main scenarios of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), which led to one of the longest-running dictatorships of the 20th century (1936-1975), only comparable to that of the Portuguese Salazarist regime (1933-1974). Although the latter lasted even longer, the distinguishing characteristic of the Franco dictatorship is its military character -under the absolute leadership of a General, Francisco Franco- as victors of a war that left a deep mark on the collective popular memory, which still today continues to generate repercussions and a wide impact considerably conflictive.

During the three years and a half that lasted the Spanish Civil War, Madrid presented its own peculiarities: it was the capital of both the front line and of the rear-guard. The city endured the siege of Franco’s troops from November 1936 till the end of March 1939, with an extensive battle front surrounding the Manzanares River and the University City on the north, west and south sides of the capital. Literally, some streets in Madrid ended up in front trenches under the effect of continuous bombings. Madrid was the first European capital city to suffer aerial bombings – already in the summer of 1936 – as an experiment part of the classic “total war” during the 20th century put into practice during the Second World War. The land bombings carried out from the nearby artillery positions of the rebels caused, in addition to a high mortality rate still to be properly quantified, the systematic demolition of its streets and buildings. There were other consequences brought by the war and etched in the memory of the people of Madrid: hunger, hardship, ration books, etc. shattered lives, in short, and the trace of horror and scarcity in the popular memory.

However, Madrid was not only the capital of the front line, the “Heroic Madrid” was praised by the political organizations that participated in the resistance against the rebels who were militarily supported by the German Nazi and Italian fascist regimes, as a consequence of which it won a worldwide repercussion for the antifascist cause. Madrid was also the capital of the rear-guard; in this city took place a kind of social “revolution” since the moment different working and anti-fascist organisations (trade unions with socialist, communist and libertarian ideologies) obtained important share of the political power in the city through a committed defence during the second half of 1936 and part of 1937. This process was only possible thanks to the particularly dramatic conditions of the summer and, above all, the autumn of 1936, with the enemy at the gates of the city and the Republican government fleeing to Valencia. This revolutionary dynamic lasted well into 1937 and generated a repressive process against all those people who were branded as enemies or “hostile” to the Republic, according to different popular committees with a particularly strong position in the working class districts of the suburbs. As a result, thousands of people were killed according to different models. During the summer of 1936 most of the murders were committed by different popular committees with a relative autonomy; however, between October and December of the same year, a series of committees and parties – with representation in the formal structures of government – designed and executed a secret and never-recognized plan for the murdering of thousands of alleged “hostile” people. This systematic plan of murdering claimed the lives of around two thousand men according to the most rigorous studies, extra-judicially executed around the nearby towns of Aravaca, Paracuellos and Torrejón de Ardoz. The form used and the premeditated nature of the massacre, i.e. prisoners were get out under pretext of their transfer to Valencia and their execution on the edge of the gutter at the outskirts of the capital, also left a deep mark on the popular memory of the city’s middle and upper classes, especially in those neighbourhoods in the centre surrounded by the working class suburbs. The “slaughter of Paracuellos” would thus become an important part of the memory built by the victors in 1939 as one of the main atrocities carried out by the “Red Madrid”.

Apologia memoriae and repression

April 1, 1939, is the official date of the victory over the legally constituted authorities of the Republic, and from this date on, the new military regime was almost obsessively engaged in building a whole “memorial policy” with the aim of justifying and legitimizing the military “uprising” and its triumph after the three years of war, sanctioned, by the way, as a “Crusade” by the Catholic Church. In the case of Madrid, the “victims of the red barbarism” were remembered and praised. Their corpses were exhumed from ditches and ossuaries to be buried in dignified tombs for payment, at the expense of the public funds. As for their names, they have since appeared in witness books, in school textbooks of several generations, in stone monuments, on bronze plaques and on the crosses installed on the walls of so many churches in the Spanish territory, thus physically and symbolically shaping the tenacious account of the “Fallen for God and for Spain”. Furthermore, these names were stamped on the plaques of the streets of thousands of towns and cities for everyone’s information, beginning with the capital city where there are still a good number of them.

It is dramatically remarkable that this process of memorial exaltation, particularly speaking of the cemetery in Madrid, took place at the same time that a systematic physical elimination of the defeated in the same space. Between April 1939 and early February 1944, almost three thousand people were executed by firing squad in the vicinity of the Almudena cemetery and buried there in cheap, emergency graves, the so-called “charity graves”. In a formally occupied city, and a country in a state of war until 1948, General Franco’s military dictatorship tried hundreds of thousands of people throughout the country in court-martials or emergency military summary trials, imposing all kinds of prison sentences and, of course, death by firing squad or “garrote vil”, the traditional and infamous Spanish death penalty. These court-martials were initiated exclusively by military personnel, on the basis of accusations and denunciations that were largely based only on rumours or on negative reports of conduct drawn up by the victors. The real chances of defence for the accused were slim and there was no judicial guarantee at all during the trials.

As a result, 2,937 people were executed in Madrid during this period. Most of their relatives could not even recover the bodies to bury them in an appropriate tomb: only about four hundred managed to escape the fate of the common ossuary of the cemetery, upon the prescription of the ten years in the charity tomb. Those who succeeded in doing so, after the corresponding request to the military authority, could only perform the religious service and burial “in the strictest privacy”, and “without any ostentation nor ceremony”. However, this situation only affected the bodies, so… What about the names? In the families of the defeated, the memory of what happened had to survive hidden, when it was not lost in oblivion. More than eighty years after the murder, some families were still unaware that their relative had been executed in the post-war period, and not during the war at the hands of the “red army”. Shifting the focus from the family memory to the historical record, during the dictatorship it was not possible to count the number of victims executed in the vicinity of the Madrid cemetery, but this situation persisted during the following decades, even during the democracy. Researches and relatives did not have any access to the documentation, in the custody of the Army also responsible for the courts-martial, until well into the nineties. It was not until 1997 when it was possible to perform the first study on the victims, carried out mainly thanks to the consultation of the cemetery documentation.

Validity of the Damnatio memoriae

Only in 2018, on the initiative of the Office on Human Rights and Memory of the Madrid City Council, which commissioned a list of victims to a team of historians by consulting the records of the cemetery – which was closed again to researchers since the end of the 1990s-, it has been possible to publish an exhaustive list of the people executed in Madrid during the immediate post-war period: the 2,937 persons mentioned, including 80 women (1). The ultimate goal of this list from the beginning was to build a memorial monument in the cemetery area “in memory of the victims of Franco’s violence”, where all the names would be included (2). It would be easy to think that this was a praiseworthy legitimation, immune to any questioning, especially in view of the “deficit” of memory regarding the Franco repression that has characterised the municipality of Madrid for decades. A city which still has to fight against political forces and even judges to assert its decision to rename its streets. Let’s not forget that the names of well-known generals of the 1936 uprising are now displayed in many streets of the capital.

And yet, even today, some relevant voices have a position against the memorial to include the names of those 2,937 people even when they are part for example of the Historical Memory Commissioner created nearly a year ago by the Madrid City Council. Their recommendation was based on the fact that this list allegedly included the names of agents of the political violence committed during the civil war in Madrid, calling them “chequistas”: a name that is as inaccurate as infamous and constantly used during the dictatorship. In mid-June 2018, the Commissioner concluded his advisory work with the City Council in terms of policy memory, but not before some of its members – i.e. The writer Andrés Trapiello, proposed by the regional political party Ciudadanos, expressed their criticism on the decision, approved in the plenary session (3), to include all the names of the people executed in the projected memorial monument of the cemetery (4). The argument used by Ciudadanos and the Popular Party is that sectarianism has prevailed over dialogue, suggesting their position would be the most objective and equidistant, as an opinion sanctioned by the historians present at the Commissioner, who, more or less tacitly, would have shared it.

In fact, as noted elsewhere in the heat of the controversy (5), the presence of these names in the memorial was a result of two situations: the decision approved months ago by that same Commissioner (somewhat forgetful of what approved by himself) and a flawless logic about the recognition of a group of victims homogeneous and perfectly differentiated from the historical point of view: the people executed after the trials which took place during the post-war in the Franco’s dictatorship. An evaluation of the reasons that brought to each execution would have been like submitting them to a new trial by supporting and therefore validating a few irregular procedures given the lack of any legal guarantee whatsoever in their military processes. The solution suggested by some of the members of the Commissioner when proposing an anonymous memorial would have resulted in an anonymous memorial instead of a place to remember, by keeping in the oblivion the whole group of victims of the immediate post-war period, something that would be impossible at a technical level. A memorial without names for these victims would have an effect opposed to a memorial, a forgetful memorial of the victims of the Franco’s regime in the city of Madrid.

This hypothetical memorial of erased names would also have been an affront to the relatives of those victims, who for almost twenty years have been fighting for the recognition of this episode through the group Memoria y Libertad, and for the full names of their relatives to be engraved in stone or bronze. At a practical level, it would have implied a new twist to the policy of damnatio memoriae prevailing in the dictatorship, also representing an affront regarding the other victims’ names – those resulted from the Republican violence of 1936 constantly reproduced and engraved on monuments, plaques and streets. Some attitudes have not changed, and insisting on a large time span ranging from the Franco regime to the democracy of 2018, keep judging and erasing, instead of understanding or honouring. All of this highlights once again the current political conflicts and the attribution of new significances in the world of politics of memory.