Oriol López Badell, European Observatory on Memories (EUROM)

Cover image: Illustration of the misnamed Negre de la Riba at the pier, published in Visions barcelonines, 1760–1860. Els barris de la Ciutat by Francesc Curet and Lola Anglada, 1953.

The misnamed Negre de la Riba was, for decades, one of Barcelona’s most popular figures. Its origins date back to the 18th century, when it adorned the prow of a ship engaged in trade between Europe and the Americas. The figurehead, thought at the time to represent an African warrior, would go on to become a well-known character in Barcelona’s collective memory.

When the ship was scrapped in the 19th century, the figure was purchased by Francesc Bonjoch, a maker of wooden barrels and nautical tools, who placed it on the façade of his shop on the Riba dock. Between 1860 and 1870, the figurehead was a commercial attraction and soon became a local curiosity for passersby. At that time, the dock—in the heart of the Barceloneta neighbourhood—was a lively place, a meeting point for residents and visitors who came to watch the bustle of the port or greet the mysterious Negre de la Riba.

During the second half of the 19th century, the figurehead became a genuine popular icon. It appeared in satirical and literary publications and even inspired theatrical parodies. Its fame, shrouded in legend, gave it an air of mystery: many magazines reported the belief that the Negre de la Riba would carry off disobedient children, and chronicles tell us that more than one parent took advantage of this superstition to scare youngsters into good behaviour.

Around 1900, with the redevelopment of the Riba dock, the figure changed hands several times and began a journey through the city’s neighbourhoods, until in 1934 it was finally donated to the Maritime Museum of Barcelona. It was successfully exhibited for a few years, but its memory gradually faded during the 20th century, kept alive only by a few

local scholars and history books.

The True Identity of the Figurehead

In 1996, restoration work carried out at the Maritime Museum revealed a surprising fact: analysis of the clothing and hairstyle showed that the figure did not represent an African man, as had long been believed, but rather an Iroquois Native American from the northeast of North America. This reinterpretation exposed the misreading and racialised lens through which the piece had been viewed for more than a century. The dark colouring of the figure—caused either by age or, according to some sources, by a fire aboard its ship—and its damaged appearance had fuelled a vision full of stereotypes. For years, the figurehead had been associated with a dehumanised image of “the other”, frightening children as a symbol of the unknown.

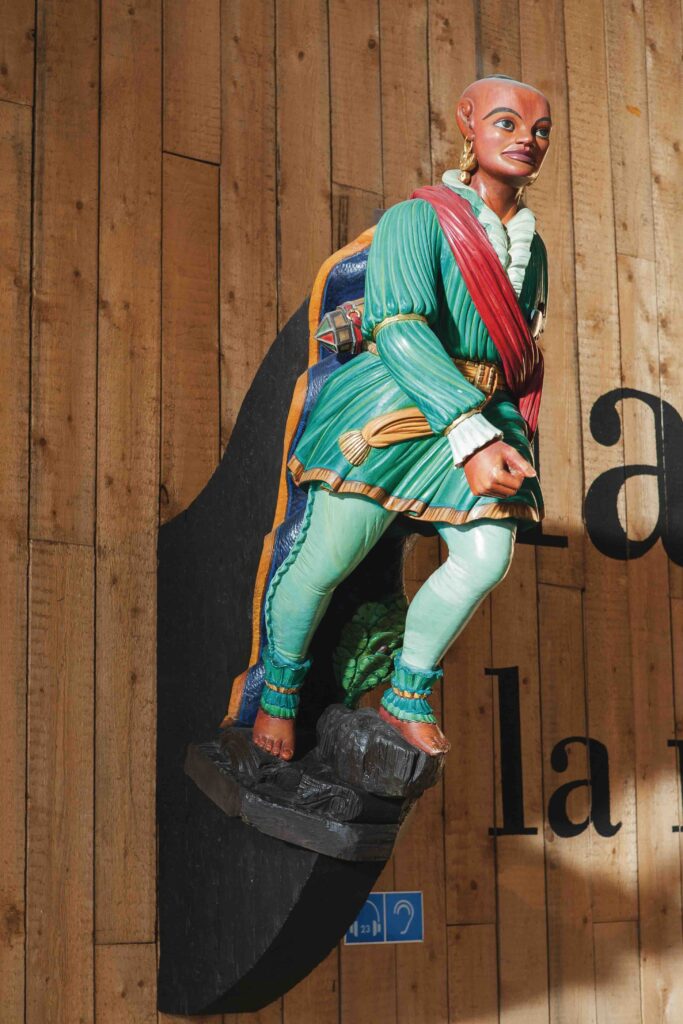

During an earlier restoration, a raised arm holding a knife—never part of the original design—had even been added, reinforcing this distorted reading. Today, the restored figurehead, with its original colours recovered, can be admired at the Maritime Museum.

Over time, interest in the figure was rekindled, and in 2003, coinciding with the 250th anniversary of the neighbourhood’s founding, the artisan workshop Constructors de Fantasies, with support from Barcelona City Council and local residents, created a fibreglass replica. This new version, installed on the façade of a building near the market square, helped recover the symbol and fully reintegrate it into the neighbourhood’s festive heritage, where it has featured prominently in celebrations and parades over the last two decades.

An Exhibition that Sparked Controversy

In 2024, I had the opportunity to curate an exhibition dedicated to this local figure with the aim of presenting it through a critical lens. The exhibition was arranged around three main themes: reconstructing the figurehead’s history through archival documentation; creating dialogue with other objects at the Ethnological Museum of Barcelona representing popular myths used to instil fear in children; and offering a decolonial interpretation of the piece. After months of work and with the active participation of Barceloneta residents, the opening day arrived with a parade led by the figurehead.

The procession travelled from the Museum of Ethnology and World Cultures to the Casa de la Barceloneta 1761, a small municipal facility devoted to preserving the history and memory of this seaside neighbourhood where the exhibition was hosted.

Two days later, a digital magazine published an article entitled “Barcelona Exhibits a Monument to Racism,” sharply criticising the presence of the figurehead in the museum, the role of the Museum of Ethnology and the exhibition’s overall approach.

The author, however, had not visited it; her piece was based on a temporary sign placed at the museum entrance announcing the exhibition with a short description and its dates. This explains why neither that article nor subsequent social media posts mentioned the section of the exhibition which took a critical look at Barcelona’s colonial past and the role of fortunes derived from the colonies in the city’s economic and urban development. In hindsight, it is fair to acknowledge that this section could have benefited from more space and resources to better convey its critical message and prevent misunderstandings or discomfort.

An Open Debate: Rethinking the “Negre de la Riba”

The controversy surrounding the exhibition prompted the organisation of two public debates in February 2025, bringing together residents, associations and professionals from the cultural and social inclusion sectors. The goal was to reflect on how cultural institutions—and society at large— represent diversity and to reconsider the role of the misnamed Negre de la Riba in collective memory.

The first roundtable gathered specialists and anti-racist activists to discuss the exhibition’s historical and artistic approach. The second gave voice to members of the public and representatives of organisations such as Fedelatina (the Federation of Latin American Associations of Catalonia), along with historians, anthropologists and artists from diverse backgrounds.

The debates underscored the need to reinterpret certain popular figures to ensure more inclusive and respectful representations.

Some participants pointed out that the exhibition’s critical approach to colonial history and the transatlantic slave trade did not go deep enough, suggesting that these aspects could have been explored further. The opening parade through the old city was also criticised by some as potentially insensitive toward racialised communities. The Museum of Ethnology acknowledged these concerns, admitting that some traditions may perpetuate racist messages without conscious intent.

At the same time, other participants—such as Fedelatina’s representative—noted that the exhibition was a positive example of decolonial practice in the Barceloneta neighbourhood, stressing that institutions must confront colonial legacies, reflect on their myths and decide whether some should be dismantled.

Meanwhile, some local residents felt that the controversy had been blown out of proportion and that the celebrations involving the figurehead had always been positive, though they agreed that certain aspects should now be reconsidered.

Overall, the two sessions generated valuable discussions and led to three specific recommendations for reinterpreting the Negre de la Riba: reviewing its name; critically contextualising it; and involving racialised communities in decisions about its representation.

The figurehead restored in 1996 and currently on display at the Maritime Museum of Barcelona. Photo by the Maritime Museum of Barcelona.

Fibreglass copy of the figurehead made in 2003. Photo by the author.

The Neighbourhood Leads a Process of Reinterpretation

The controversy surrounding the figurehead and the accusations of racism directed at residents provoked a strong emotional response in Barceloneta—a traditionally working-class neighbourhood that has welcomed diverse cultures since its creation in the 18th century.

The area has long suffered from tourism pressure and gentrification, which have displaced many locals. Consequently, numerous residents involved in the Negre de la Riba’s festivities see themselves as defenders of popular, grassroots culture.

For locals, the parades featuring the figurehead are a form of community expression that brings the symbol closer to the public while also offering a way to reflect on the city’s colonial past. They acknowledge, however, that the traditional 19th century name may now be considered offensive by some.

Significantly, the song written years ago to accompany the figurehead explicitly references Barcelona’s colonial and slave-trading past.

Today, a group of residents—led by the Constructors de Fantasies workshop that built the replica in 2003—are engaged in a process of reflection aimed at resignifying the figure and turning it into a critical symbol of popular struggle. They recognise that they had not previously perceived the figure’s potential racial implications and are now working to address them. Recently, they installed a plaque beneath the figurehead reading: “The misnamed Negre de la Riba is much more than a maritime sculpture. It is the legendary figurehead of Barceloneta, a nightmare for slave traders, brought to life by the people.”

They have also published a manifesto proposing to rename the figure, removing the word negre, and use it as a tool to explain and acknowledge the city’s colonial and slave-trading history. The group has reached out to organisations such as Top Manta—the Barcelona street vendors’ union made up mostly of migrants—to involve them in the discussion about the figurehead’s reinterpretation.

This process shows how a controversial figure is being transformed into an instrument for critical reflection and memory, testing the community’s ability to create participatory spaces and involve diverse social actors in recognising the past and building a more inclusive representation of the neighbourhood. What remains to be seen is how these efforts will take shape in practice.

Open debate with local residents, cultural and community organisations, 2025. Photo by the author.