Andrew Davies, University of Liverpool, and Nick White, Liverpool John Moores University1

Liverpool’s waterfront1 is currently undergoing major change as part of the Waterfront Transformation Project, a multi-million pound process coordinated by National Museums Liverpool with multiple funding bodies and significant community involvement2. This project seeks to reimagine the city’s historic docks and port in the context of the legacies of colonialism which have shaped the city. The intention is partially to renovate some of the historic maritime architecture/facilities in Liverpool’s city centre, but largely serves to better incorporate some of the histories and legacies of the docks into the visitor experience. This includes wider recognition of the historic diversity of Liverpool’s population, including those communities who have been traditionally marginalised or excluded from official commemorations or museum displays. In addition, the reimagination project is about recognising the docks/waterfront as a space which

connected Liverpool to other parts of the world – particularly West Africa, the Caribbean and the Americas during the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Whilst Liverpool’s interconnected dock system stretched for miles along the Mersey estuary, the Waterfront Transformation Project seeks to make significant alterations to a small but significant set of buildings and structures which are in the heart of the city and are a major set of tourist attractions. Since the 1990s, the tourist sector has been a major part of Liverpool’s economy and ‘The Docks’ as they are commonly called, are the site of museums (Tate Liverpool, the Maritime Museum, the International Slavery Museum and the Museum of Liverpool) as well as the Liverpool Arena, Conference Centre and significant numbers of bars and restaurants. Nearby are the ‘Three Graces’ – the iconic Liver Building, Cunard Building and Port of Liverpool Building which are emblematic of the city’s public representation as a maritime and financial centre. However, this landscape has traditionally made little explicit reference to the city’s origins as a major imperial port.

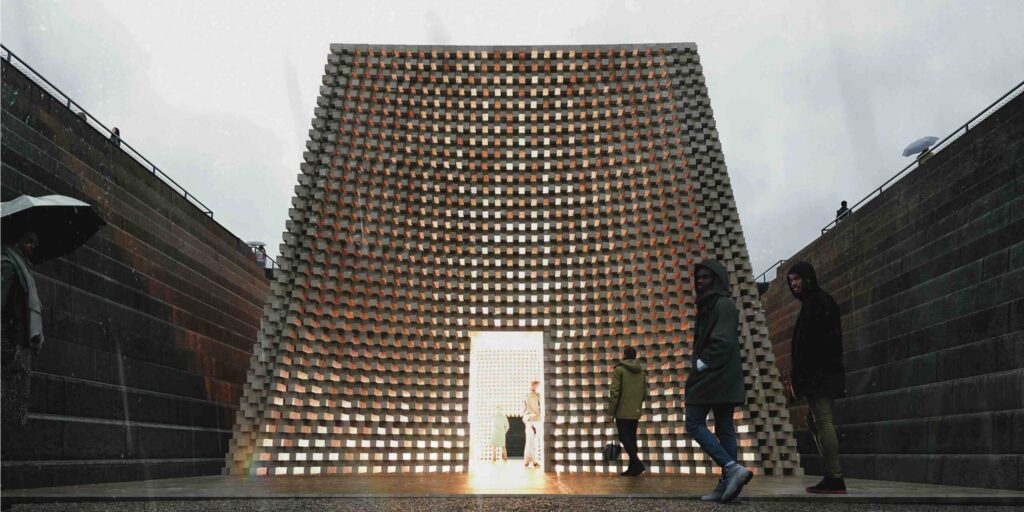

Proposals for Liverpool’s Canning Dock © Asif Khan Studio

Liverpool, Slavery and Empire

Liverpool’s growth as a city was predicated on the growth of trade facilitated by the expanding docklands, of which the most significant in the city’s early growth was the transatlantic slave trade. In the 1690s, Liverpool was little more than a fishing village, and its prodigious growth into a city of around 80,000 people by 1800 was largely financed by transatlantic slavery – by the 1740s it was the UK’s (and probably Europe’s) principal port involved in the transatlantic slave trade. By 1797, the abolitionist clergyman Reverend William Bagshaw Stevens was able to claim that every brick in Liverpool was cemented by the ‘blood and sweat’ of the enslaved labour of black Africans.

However, even after the 1807 abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire, and the 1833 abolition of slave-owning, the port and its associated trade connected Liverpool to the wider British Empire, as well as to goods produced by enslaved people in the Americas (for example, many merchants in Liverpool supported the Confederacy in the US Civil war). This ensured that Liverpool’s population was more diverse than many other British cities. The city has some of the longest-established populations of Black, Chinese and South-East Asian residents in the UK, combined with earlier communities of seafarers from Russia, Scandinavia and elsewhere in Europe.

Liverpool was, by the early-twentieth century, one of the British Empire’s pre-eminent cities – historian and Director of London’s V&A Museum Tristram Hunt listed it in his 2014 book as one of the ten cities which ‘made’ the British Empire. Like many UK cities with diverse populations, Liverpool has a complex history of solidarity and community resilience punctuated by moments of violence and despair. These include, but are not limited to, the 1919 port city riots where thousands of the white-majority population attacked the blackminority community and murdered a Bermudan seafarer named Charles Wotten in the waters of the docks, as well as the forced deportation of around 2,000 Chinese men from the city in 1945-6, permanently splitting fathers from their wives and children and which was only acknowledged in 2022.

Liverpool’s twentieth-century economic decline is intertwined with these stories, and its public institutions have often ignored or marginalised these inconvenient imperial histories and the impacts they had on the various communities in the city. As such, many minority and working-class communities within the city are often sceptical of the intentions of local and national authorities.

Museums, Memorials and Commemoration in the Docks

Attempts to redress these omissions from the city’s public spaces have been long in the making. The importance of the city’s historic collections means that its most significant museums are publicly owned and governed by National Museums, Liverpool (NML). As a result, unlike many municipal and provincial museums in the UK, they are sponsored and effectively governed by the UK Government’s Department for Culture, Media and Sport rather than by local authorities. Whilst this means NML and its holdings are bound to national/ministerial conventions and therefore heightened scrutiny, it also means NML’s museums are free to enter and have a degree of extra financial security compared to many municipal museums in the UK. The current Waterfront Transformation Project, led by NML, is closely tied to the buildings, collections and holdings of three of NML’s museums––the Maritime Museum and the International Slavery Museum, and the Museum of Liverpool.

Proposal for Double Lever Bridge Raised ©️ Asif Khan Studio

It is important to note here the intertwined history of the MM and the ISM. Merseyside Maritime Museum – as it was then known – housed in the Royal Albert Dock complex, was established in 1980 and fully opened in 1984. In its initial years, like many maritime museums, it focused largely on displays of ships, boats and other maritime ephemera––but the museum was criticised for not including reference to Transatlantic Slavery. In 1994 a specific exhibition was created––Transatlantic Slavery Against Human Dignity––although this was also subject to criticism, especially for not consulting in its creation members of the Liverpool communities with historic ties to enslaved peoples. This fed into the establishment of the International Slavery Museum in 2007, symbolic as the bicentenary of the 1807 abolition of the Slave Trade. ISM is a separate museum but was housed within the Maritime Museum building on its 3rd floor. ISM was immediately the subject of extensive local, press and academic attention, not least because of its overt political stance. The initial ISM displays did involve much more community consultation than previously at the MM, but it was recognised that this process was imperfect and the limited space available in one floor of a different museum could not do justice to the full story of Liverpool’s involvement with transatlantic slavery. ISM has expanded since opening to include an adjacent building – the Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. Building (formerly the Albert Dock’s historic Traffic Office) and is now a significant presence within the cultural landscape of the city. Both museums as well as NML, then, have been the subject of scrutiny and have been subject to rigorous critiques over their involvement of local communities in the design of their spaces.

Co-Producing a New Waterfront

It is in this setting that the Waterfront Transformation project is making its intervention, aiming to involve and include communities excluded from such processes in the past. The project is one of the largest attempts to reimagine the city’s public spaces in living memory, and is significant as it is not primarily concerned with regeneration as a means of improving the economy of the city (although this is obviously an important corollary). The project also sits within a wider context of contentious urban planning decisions within the city in recent years––until 2021, the waterfront in and around the city centre was one of the core areas of the wider UNESCO World Heritage site of ‘Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City’. Wider urban redevelopment projects along the waterfront extending beyond the city centre – described as ‘vandalism’ in a major national newspaper3–– saw the inscription being removed in 2021.

The remit of the Transformation Project, which was launched with a public competition in 2021,4 included re-orienting the interiors of ISM and MM to improve the accessibility and interpretation spaces of the but also to consider how to incorporate the docks and wider waterfront area into the story of Liverpool. Since the waterfront shifted towards a site of leisure in the 1980s, many areas remained shaped by their industrial past and were hard to access and little used as a result. The Canning Graving Docks, where ships (including slave ships) had been refitted and repaired since the 1700s,

are large spaces which were either empty or contained decaying ships inaccessible to the public. Thus, improving the public’s ability to visit and engage directly with these spaces was a key aim of the overall project.

From the beginning of the current project, clear processes were established with representatives from various communities to co-produce the outcomes. These include representatives from different ethnic communities, but also historic and maritime associations within the city. For example, since the opening of ISM in 2007, the RESPECT group5 was established to improve the representation of historic and present-day inequalities in the museum’s spaces. RESPECT now provides strategic advice and support across NML’s activities and is an important advisory group for the Waterfront Transformation Project. Elsewhere, local creative organisations such as Writing on the Wall and 20 Stories High brought their expertise on storytelling and engaging with under-represented communities through the arts into dialogue with museum and planning professionals. Other expert groups include maritime historians (both professional/academic and independent scholars) and historians of transatlantic slavery. For instance, NML staff have been working with the Liverpool Black History Research Group to explore the history of who lived and worked the historic docks.6 This approach has been important in ensuring co-production of the new waterfront feels genuine rather than tokenistic and involves communities throughout the entire process. As noted above, this has been an extended process which has taken decades since the first attempts to do justice to Liverpool’s past.

Emerging Outcomes and Ongoing Developments

The Waterfront Transformation remains in progress as we write in 2025. With funding secured from the National Heritage Lottery Fund and the UK Government’s Levelling Up Fund, work has started on the major redevelopment of the interiors of the Maritime Museum and International Slavery Museum. In the next phases, the Canning Graving Dock will form the centrepiece of the Waterfront’s outdoor spaces. Architecture firm Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios and National Museums Liverpool are working with multiple partners to develop the Dr Martin Luther King Jr. building and the Hartley Pavilion. Inter alia, this will involve a prominent new entrance to ISM, improving visitor orientation and opportunities for reflection, while developing MM as a multifunctional space, facilitating community collaboration, events, and educational activity.

The collective nature of the Project is encapsulated by Ralph Appelbaum Associates, who are contracted to redesign MM’s and ISM’s exhibition spaces, when they state: “Together, we will honour Liverpool’s Waterfront as a sacred ground – a place that reverberates with the sights, sounds and souls of all those connected to its global history.” The significance of such an endeavour for building an inclusive story of the colonial pasts of major European cities like Liverpool means

that many should be interested in the Waterfront Transformation Project’s eventual outcomes.

- Both Andy and Nick are the Co-Directors of the Centre for Port and Maritime History (CPMH), a collaborative academic initiative between the University of Liverpool, Liverpool John Moores University and National Museums Liverpool. CPMH runs regularseminars and events related to maritime history in and around Liverpool, and members have been involved in various aspects of the consultation process for the Waterfront Transformation Project ↩︎

- https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/waterfront-transformation-project ↩︎

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/jul/21/liverpool-unesco-world-heritage-status-

stripped?ref=livpost.co.uk ↩︎ - https://www.placenorthwest.co.uk/design-contest-to-breathe-new-life-into-liverpool-waterfront/ ↩︎

- https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/about/respect-group ↩︎

- https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/news/of-people-and-place ↩︎