Monika Baár, European University Institute

Cover Picture: The tomb of Louis Braille at the Panthéon in Paris. Lucas Werkmeister, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The field of memory studies has flourished in recent years. However, the memory culture of people with disabilities remains a blank; it still belongs to what might be termed “subaltern memories”. Why is it both worthwhile and necessary to pay more attention to this topic? While this legacy has an intrinsic value, as part of humanity’s heritage, there is also an ethical aspect: the struggle for inclusion of persons with disabilities goes hand in hand with securing a place for them in history and in commemoration practices. As the saying goes, memory is just as much about the future as the past. Maintaining and cherishing a marginalised group’s identity and heritage requires both forward-looking action and active engagement with the past.

In this article, after reflecting on the reasons for the silence that has long characterised this field, I will discuss several examples of commemoration and remembrance from the twentieth century. I will also argue for the importance of recognising and preserving the memory of disability social movements. Of particular significance is the remembrance of the creative ways in which people with disabilities have challenged the status quo—both through outspoken protest and through more subtle forms of resistance. Including such examples of agency helps challenge the two dominant representational tropes: the tragic victim and the overcoming superhero. It also contributes to building a more inclusive memory culture, one that reflects the diverse and multifaceted nature of human experience.

Why, then, has the intention to commemorate disabled people appeared so late on the agenda of heritage studies, even compared to other marginalised groups such as women, ethnic minorities, LGBTQIA+ people, migrants, and displaced persons? One key factor is that disability constitutes an extremely heterogeneous category: it has no universally accepted definition, and its boundaries have shifted over time. Even the terminology remains contested. For example, while the United Nations Convention adopts the designation “persons with disabilities,” many people prefer the term “disabled people,” and this article uses both variants. Often, individuals with one type of disability feel little sense of commonality with others, and this fragmentation can hinder the development of shared memory practices.

A second factor is visibility. For any group to achieve greater recognition, it must first be adequately represented. When its voice goes unheard, it requires strong and effective advocacy to amplify it. This is not merely a symbolic issue but also a practical one with financial implications: the creation and maintenance of archival collections, the organisation of museum exhibitions, and the construction of memorials all require substantial funding. In the neoliberal marketplace of the heritage industry, citizens are often regarded as consumers, and market logic does not necessarily favour the inclusion of people with disabilities. Nevertheless, silences can be broken in alternative ways. Artists, for instance, often play a vital role in fostering remembrance when more formal or institutional modes of commemoration are absent.

The victims of the two World Wars

Disability may be congenital, acquired later in life through accident or illness, or sustained in war. Of these categories, disabled veterans have received the most consistent attention in European memory: they were honoured for having shed their blood and sacrificed their bodies and minds in the service of their countries. The First World War, for instance, left an indelible mark on European memory cultures. The fate of permanently disabled soldiers returning from the battlefields became a recurring theme in novels, films, and paintings. Yet in public spaces, their representation remained limited: monuments typically commemorated the fallen soldiers or, more symbolically, the unknown soldier. One notable exception is a monument located in Haparanda, a city at the northernmost edge of Sweden’s coastline, near the Finnish border. During the First World War, the International Red Cross facilitated the exchange of more than 63,000 wounded and sick veterans between Russia and the Central Powers in neutral Sweden. The veterans suffered from various conditions, including gunshot wounds, tuberculosis, and mental illness. Around 200 of them died in transit and were buried in the churchyard where the monument now stands. The transport operation received considerable media coverage, as the “army of misery” provided many civilians with their first direct encounter with the horrors of war.

During the Second World War, people with disabilities—including those with mental illness or hereditary conditions—were among the first to fall victim to the dehumanising ideology of the Nazi regime. The principles of eugenics sought to “improve” the genetic quality of the population on the basis of racial superiority. This led to the systematic implementation of euthanasia programmes designed to eliminate those deemed “undesirable,” most infamously through the Aktion T4 programme. Disabled people were, in fact, a test case for the mass killings later extended to Jewish people and other persecuted groups.

The hierarchies of remembrance often reflect the moral values of societies. Although people with disabilities were the first victims of the Holocaust, they were the last to be commemorated. Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial, dedicated to Jewish victims, was inaugurated in 2005 and quickly became an iconic site. A memorial followed it to the LGBTQI+ community in 2008, and another to the Roma and Sinti victims in 2012. The T4 monument, situated in Berlin’s Tiergarten district, from where the killings were administered, consists of a 24-metre-long structure made of translucent sky-blue plexiglass. The tone—known as Prussian blue—is identical to the pigment found in the chemical compounds of Zyklon B gas used in the gas chambers, traces of which can still be seen on their walls. This “murderous shade” has thus become a powerful symbol of remembrance.

In the Netherlands, the Dovenshoah monument in Amsterdam, unveiled in 2010 on the former site of a school for the deaf and hard of hearing, commemorates Jewish deaf victims. Three words appear on the monument in sign language: world, remain, and deaf. The accompanying inscription reads: The world remained deaf / In memory of the Jewish Deaf victims of the Nazi regime, 1940–1945. The message is deeply symbolic. While the word deaf is often understood as implying absence or deficiency, its meaning is inverted: it is the hearing world that was “deaf” to the cries of the victims.

In contrast, another monument in Poland highlights active resistance. The Monument for Deaf Insurgents, located at the School for the Deaf in Warsaw, honours the school’s alumni who fought in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising as members of the Home Army. The monument was unveiled by Karol Stefaniak, himself a deaf veteran, who participated in the uprising at the age of thirteen. Revealing more of these acts of resistance helps challenge the enduring stereotype of disabled people as passive victims.

Exceptional individuals: the legacy of Louis Braille in the twentieth century

Another form of remembrance centres on individuals of exceptional achievement. These figures are often able-bodied educators or advocates for people with disabilities, but one remarkable exception is Louis Braille (1809–1852), perhaps the most famous blind person in history. Born in the French village of Coupvray, Braille lost his eyesight at the age of three and later attended the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris. There, he developed a tactile communication system for the visually impaired which now bears his name. The Braille system allows users to read and write the same texts as those printed in conventional fonts, transforming literacy and education for generations of visually impaired people.

The commemoration of Braille’s legacy reflects a common feature of memory culture: anniversaries, particularly those marking a birth or death, often spark new initiatives. Initially buried beside his parents in his home village, Braille’s remains were transferred to the Panthéon in Paris on 22 June 1952, the centenary of his death. This pantheonisation represented the highest civic honour France can bestow—an accolade shared with figures such as Voltaire and Victor Hugo. During the ceremony, the renowned American educator and disability advocate Helen Keller (1880–1968) compared Braille’s contribution to Gutenberg, the inventor of the printing press. His legacy continues to be celebrated annually on 4 January, designated by the United Nations as World Braille Day since 2019. The observance is part of the UN’s commemorative days, weeks, years, and decades, aimed at promoting advocacy and raising awareness through governments, civil society, and educational institutions.

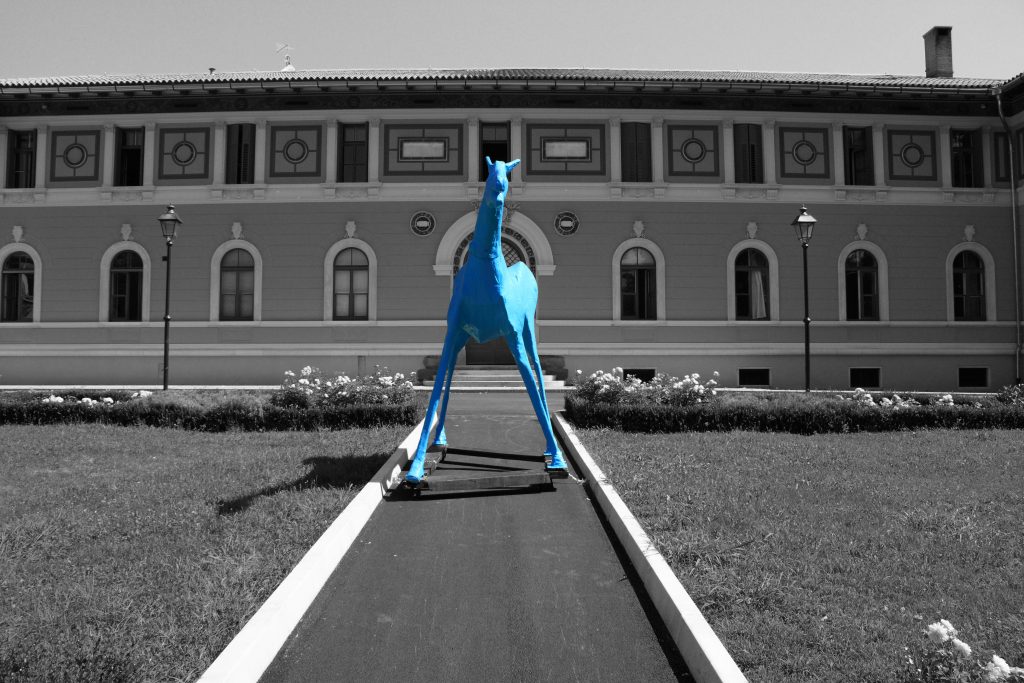

Marco Cavallo, symbol of the psychiatric revolution that began in Trieste in 1973. Itinerari Basagliani, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Remembering patients in psychiatric hospitals

For centuries, people experiencing mental distress were segregated from wider society and confined in residential institutions. Within these facilities, they often endured prison-like conditions, mistreatment, and neglect, rather than receiving proper care. In recent years, however, innovative forms of commemoration have emerged, including survivor-led walking tours and artistic performances held at former institutions. In the 1970s, reformist psychiatrists and anti-psychiatry movements called for radical change: they advocated the closure of asylums and the reintegration of patients into their communities. While professionals’ roles in this process have been recognised, the contributions of patients themselves still deserve greater attention.

A particularly striking case of collective memory concerns the legacy of Franco Basaglia (1924–1980), the Italian pioneer of deinstitutionalisation, and his patients. While directing various asylums across Italy, Basaglia sought to improve conditions for both patients and staff. In 1973, at the San Giovanni psychiatric hospital in Trieste, a group of artists, doctors, and patients created a large blue sculpture known as Marco Cavallo (“Marco the Horse”). The statue commemorated a real horse once owned by the hospital, used to transport laundry and waste. Patients had befriended the animal, which—unlike them—was occasionally permitted to leave the hospital grounds. Standing over three metres tall, the sculpture could only be removed for its unveiling festival by cutting a hole in the hospital’s perimeter wall, symbolising liberation and the breaking of barriers. The gesture also evoked the legend of the Trojan Horse, but in reverse: whereas the Greeks smuggled soldiers into Troy, Marco Cavallo symbolically carried freedom out of the asylum. This collaboration between doctors and patients challenged prevailing notions of antagonism and remains a powerful emblem of collective agency and transformation.

A contested monument to pharmaceutical abuse

Monuments are rarely static or universally accepted; their meanings can be disputed, reinterpreted, or even overturned. A case in point is the Contergan monument, erected in 2012 in Stolberg, near Cologne, where the headquarters of the pharmaceutical company Grünenthal are located. Grünenthal manufactured Thalidomide, first marketed in 1953 under the trade name Contergan as a tranquilliser. It was widely prescribed to pregnant women for morning sickness and insomnia despite insufficient testing. By 1961, more than ten thousand children had been born with severe limb deformities, and thousands of miscarriages had occurred. The drug was withdrawn that same year. What were called the “Contergan children” faced not only lifelong physical disabilities, but also profound social prejudice. A criminal trial in 1968 ended without convictions, and the company eventually reached a financial settlement with the victims.

The Contergan monument features a bronze statue of a child without feet and with malformed arms. Its aesthetic value has been questioned, but the deeper controversy lies in its process: the victims of pharmaceutical abuse were never consulted about how their experiences should be commemorated— or whether they wished to be at all. Many saw the monument as a tokenistic gesture, a cheap substitute for genuine reparations. At the time of its unveiling, an estimated 5,000–6,000 people still lived with Thalidomide-related impairments. As they aged, their needs for carers, accessible housing, and mobility aids increased. Instead of providing additional compensation, the company’s CEO issued an apology—an act widely condemned by survivors as too little, too late.

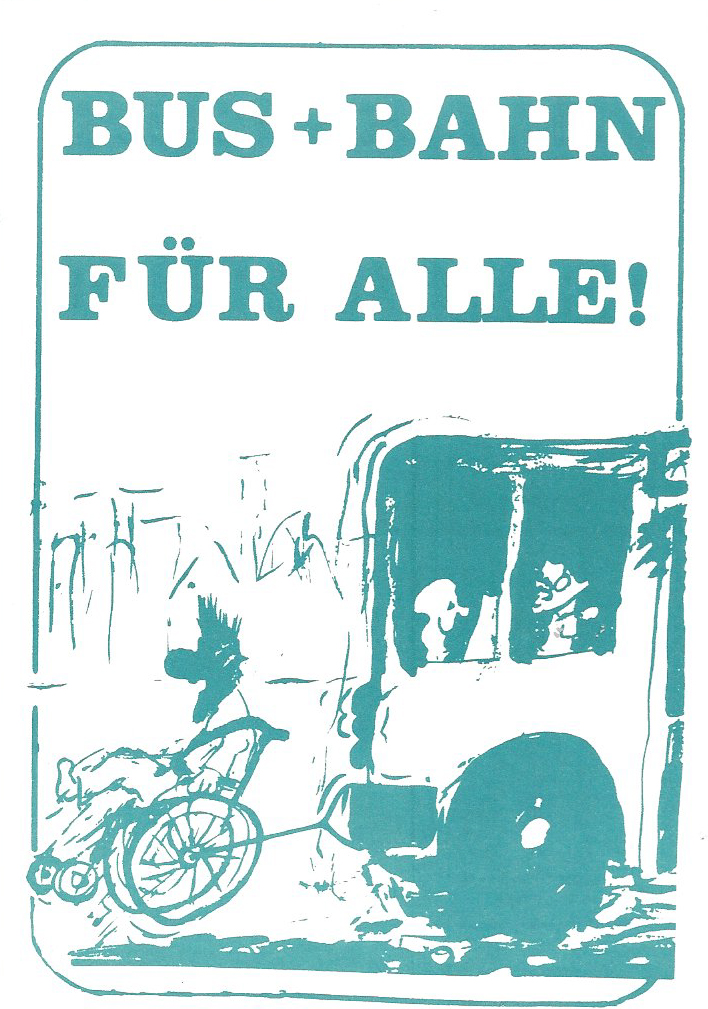

Poster produced in West Germany calling for buses and trains for all

The memory of social movements: the need for disability archives and museums

Commemoration involves much more than monuments. In addition to remembering sites of trauma and tragedy, it is crucial to commemorate the social movements of disabled people, including their struggles to frame their cause in the context of human rights. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), adopted in 2006, was preceded by decades of activism. In this respect, there are various parallels with the social movements of women, LGBTQI+ people, and the civil rights movement in the United States. The most valuable objects that help us remember these struggles are those created by disabled people themselves—letters, photographs, posters, and diaries. These sources document campaigns for more accessible environments, education, and employment during a period when wheelchair users could scarcely leave their homes and were not only physically segregated from mainstream society but also marginalised by prejudice. Activists questioned this status quo and developed a new understanding of disability.

According to this new perspective, disability is not a medical defect or an individual problem to be fixed; rather, it is a condition caused by flaws in the way society is organised. For example, when a wheelchair user cannot enter a building with only stairs and no lift, the problem does not lie in the individual’s impairment but in the lack of access. The solution is therefore to change social structures by making the built environment accessible. This approach, known as the social model of disability, focuses not on “fixing” the individual but on transforming society—its mentality and organisation.

Aktion T4 memorial at 4 Tiedrgartenstraße, Berlin. EUROM

Frustration, segregation, and humiliation drove disabled activists and their allies onto the streets. In Spain, for example, 1976 witnessed demonstrations in Madrid and Barcelona, including street protests and sit-ins held in administrative and religious buildings. In the wake of Franco’s death, activists seized the moment to demand justice and full participation in the country’s emerging democracy. Although the authorities initially resisted, the protesters embodied what Václav Havel later described as “the power of the powerless.” Their efforts ultimately contributed to the inclusion in the 1978 Constitution of an article obliging public authorities to provide specialised support for people with disabilities and to guarantee them the same rights as all other citizens. This rich heritage of activism in the 1970s culminated in a landmark event in 1981—the International Year of Disabled Persons, organised by the United Nations. It marked the first time disability was placed on the global stage. Celebrations characterised the year, but also vigorous protests in several countries. The official rhetoric surrounding the event raised expectations that could not be met in a period coinciding with the first major financial crisis of the post-war era.

The vast gap between official discourse and everyday reality generated a creative tension from which a new paradigm began to emerge. The International Year encouraged disabled people to think about their status in new ways: to stop concealing their condition and take pride in it. They demanded accessible transport and housing, and one poster produced in West Germany called for “Buses and trains for everyone.” At that time, wheelchair users in Germany could travel only in unheated goods compartments without toilet facilities.

It is essential to develop commemorative practices that highlight the creative, active, and transformative potential of activism. This shows that disability can be a source of social and cultural identity and community at local, national, international, and global levels. This requires greater attention to disability-related documents and objects in archives and museums, for instance, through searchable catalogues and temporary exhibitions. Equally important—though more difficult to achieve—is the establishment of dedicated archival and museum collections to preserve the experiences of disabled people. In the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany, such archives already exist, and one is currently being developed in the Netherlands. Alongside national initiatives, it is equally vital to ensure the preservation of archival material documenting international disability activism.

Typically, disability represents only one aspect of identity that intersects with others. The experiences of disabled women may differ from those of disabled men; those of Black disabled women may differ from those of White disabled men or women. Belonging to more than one marginalised group often leads to multiple forms of exclusion. Like any social movement, the activism of disabled people was shaped not only by solidarity but also by internal tensions and conflict. Remembering this complex and sometimes contentious heritage enables a deeper understanding of the movement’s contribution to social change and encourages reflection on the kind of society we wish to build for the future.