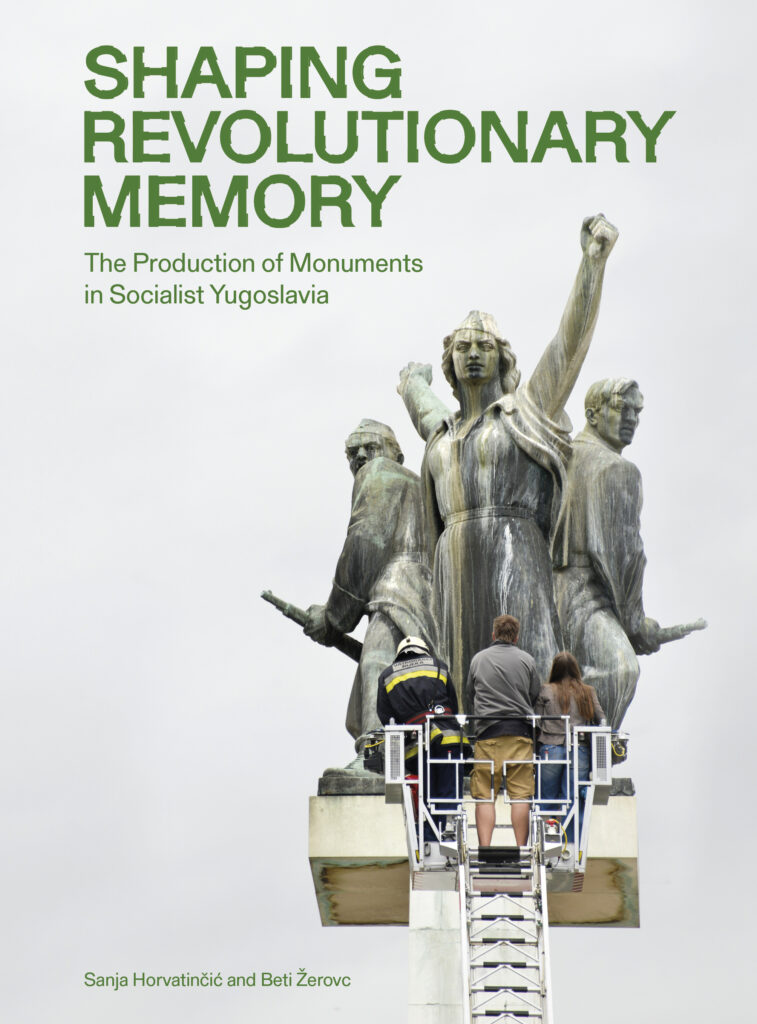

Book: Shaping Revolutionary Memory. The Production of Monuments in Socialist Yugoslavia. Sanja Horvatinčić and Beti Žerovc, 2023 (IZA Editions)

Review by Daniel Palacios González, National University of Distance Education (UNED)

Can a vast memory culture developed by thousands of people and interacting with millions over decades be fetishised and reduced to one word that strips it of all value? Perhaps that is what we see when we come across the term Spomenik. In recent years, gigantic modern Yugoslav monuments, labelled under this concept, have been shown in exhibitions, photobooks and tourist guides and have delighted scholars and artists in Western Europe and the United States. However, far from making them better known, the term has obscured the significance of Yugoslav monuments. In contrast, the book SHAPING REVOLUTIONARY MEMORY. The Production of Monuments in Socialist Yugoslavia, edited by Sanja Horvatinčić and Beti Žerovc, is an excellent antidote to the formalist and depoliticising revisionism of Western art history and memory studies on Yugoslav monuments dedicated to Anti-Fascist Resistance, People’s Liberation Struggle and the Revolution.

This book condenses authors with long years of experience working on monuments, and it is an excellent contribution in terms of theory, methodology and documentation and an example of how to research this kind of heritage. The authors of this book associate the symbolic dimension of these monuments with their material reality; they do not separate them from the specific forms of social communication they perform, nor do they separate these same forms of communication from their material bases. They show how the production of monuments after the war and the revolution did not come out of nowhere. On the one hand, there was a previous tradition of monument production that cannot be neglected (after all, Spomenik merely means ‘monument’ in the South Slavic languages).

On the other hand, shaping a series of cultural models and policies in a changing socialist context also marked the production of these monuments. In this context, the book explores the production of monuments by craftsmen and local communities based on their own agendas, as well as the major artistic productions sponsored by large institutions and federal entities. Monument production is seen as part of an economic framework that implied a new possession of the means of production (including the production of cultural memories), leading to new forms of artistic work and also of social self-representation through monuments that often pursued communicative strategies typical of an environment in which land ownership and political participation differed radically from the pre-revolutionary reality.

These situations are not free of contradictions, which the book also addresses: from the debates surrounding artistic quality versus amateurism to the poor participation of women in the structures of government and the promotion of memory policies. Therefore, the book presents a diversity of opinions and the complexity of reality. In the face of the orientalism imposed on these monuments, this work provides critical knowledge that allows us to disarticulate hegemonic discourses and brings us closer to their historical reality. At the same time, with its extensive graphic material, including more than 500 illustrations, it is the best publication on this type of monument since those produced during socialism.

The linguist Valentin Voloshinov theorized a century ago how every ideological product possesses a significance, representing, reproducing, and substituting something outside it: appearing as a sign. Thus, he considered the fact that consciousness could be manifested only in images, words, and meaningful gestures. In this way, physical images, such as monuments, become signs and, without ceasing to be part of material reality, they reflect and refract reality in a certain way. But what determines the refraction of an ideological sign? Voloshinov was categorical in this respect: the social interests in a struggle. When today, we see how monuments to Anti-Fascist Resistance, People’s Liberation Struggle and the Revolution have been reduced to an artefact attractive in form to the Western artistic gaze, (Spomeniks), we see how the same social interests in the destruction of Yugoslavia underlie the use of the term and the reduction of Yugoslav memorial culture to a select curatorship of large-scale abstract monuments.

But all is not lost. Voloshinov claimed that “the historical memory of mankind is replete with dead ideological signs incapable of being an arena for confrontation of living social accents. However, thanks to the philologists and the historians who continue to remember them, these signs still retain the last vestiges of life.” Against the death sentence of the fetishisation of the Spomeniks, the work of Sanja Horvatinčić and Beti Žerovc thus contributes to advocating these memorials of the Antifascist Resistance, People’s Liberation Struggle, and the Revolution as retainers of these vestiges of life, remaining signs capable of generating confrontation in the towns and landscapes where they still stand, in the face of post-socialist revisionism, nationalism and neoliberalism.