By Mario Proli (Journalist, Atrium Association), and Patrick Leech (University of Bologna, Atrium Association)

Images:The mosaics at the former Aeronautical College in Forlì are a remarkable artistic masterpiece from the late 1930s, created from designs by Angelo Canevari. They vividly depict the myth of flight and humanity’s pursuit of conquering the skies, as envisioned through the lens of the Fascist regime. These mosaics stand as one of the most striking examples of Forlì’s ‘dissonant heritage,’ reflecting a complex and layered historical narrative | Pictures by Ricard Conesa (EUROM)

The architectural and artistic heritage of Forlì includes a work of great value, both from a cultural and historical point of view – the mosaics in the former Aeronautical College, now a school for 11–14-year-olds. This is a truly impressive work of art dating back to the second half of the 1930s, based on drawings by Angelo Canevari and dedicated to the theme of flight. More precisely, they depict the myth of flight and the relationship between man and the conquest of the skies as interpreted by the Fascist regime. The mosaics are perhaps the most striking example of the ‘dissonant’ heritage of the city of Forlì – the ‘città del Duce’ rebuilt as a showcase for Fascism in the 1920s and 1930s, but a city awarded the ‘silver medal for its part in the Resistance (‘Medaglia d’argento al valor militare per attività partigiana’) and with a strong post-war tradition of antifascism. The mosaics have an undoubted artistic value alongside a cultural and historical value as an example of the propaganda of the Fascist regime.

This surprising visual narrative composed of black and white marble tiles (with, as we shall see, a single exception of the use of the color green on one occasion) has an intrinsic artistic value: the combination of the rediscovery of the mosaic in a contemporary key with the some of the main elements of Futurism such as the thrill of speed, the exaltation of technique, the choice of dynamic lines and geometric shapes, the exaltation of heroic deeds. All this is interpreted according to an interpretative key closely linked to the vision of the writer and poet (but also airplane pilot and military man of action) Gabriele D’Annunzio, and intimately tied to the ideology of the regime.

D’Annunzio’s Futurism

As well as being influenced by the futurism of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and “Aeropittura” (a current of the movement focused on the enthusiasm for flight, courage and power), the Forlì mosaics of the history of flight were strongly influenced by D’Annunzio’s thought, itself central to the ideology of Italian aviation during Fascism. His work included a reappraisal of the myth of Icarus, exalted in poems such as “L’ala sul mare” (‘the wing over the sea’), “Altius egit iter” (‘he flew even higher’) and “Ditirambo IV” (Dithyramb IV’) and in the novel “Forse che si forse che no” (‘Perhaps yes, perhaps no’). In D’Annunzio, however, the image of Icarus is the opposite of that in antiquity where, for example in Ovid, the curious young man loses his life for not having respected his father’s advice for him to be prudent. For D’Annunzio, Icarus becomes instead a heroic example of one who accepts a challenge, and in this he is supported by the example of Phaeton, another imprudent youth. In 1909 D’Annunzio had declared that modernity had already surpassed both the myths of antiquity and the dreams of the Renaissance and he recruited both Icarus and Leonardo as precursors. These two, in fact, became the key symbols for Fascist aviation in Italian Aeronautical Exhibition of the Palazzo dell’Arte in Milan in 1934, to whom were added the contemporary figures of Francesco Baracca (the hero of the Great War), Italo Balbo (the commander of the trans-oceanic flight to Chicago and New York in 1933) and, indeed, Gabriele D’Annunzio himself, the indomitable pilot who flew over Vienna during the First World War dropping anti-Austrian leaflets. It was this exhibition which inspired the work of Canevari for the mosaics in Forlì.

The Aeronautical College, a pearl of rationalism

The architectural context of the building in which they are located undoubtedly contributes to making the Forlì mosaics unique. The mosaics can be found in the courtyard of a large, monumental complex designed by one of the great exponents of rationalist architecture in Italy, Cesare Valle. The building was designed in the mid-1930s, built in 1937 and inaugurated in 1941 and was dedicated to the memory of Bruno Mussolini, son of the Duce and an air force officer who died in a plane crash in Pisa in August the same year. The Aeronautical College is situated at the end of the avenue (then Viale Mussolini, now Viale della Libertà) leading up from the new Forlì railway station which at the time represented the main access point to the city. The station and the avenue were also the beginning of the route taken by the political pilgrimages of the 1930s to the dictator’s birthplace, in Predappio. This was a route created and managed by the organizations of the Fascist regime to bring hundreds of thousands of people every year, often for free or at very low cost, to discover the places of Benito Mussolini’s childhood.

To fully appreciate the value of the mosaics, then, we need to take into account their architectural and urban context and the different and overlapping levels of communication involved. The building itself was a monumental complex created to inspire awe on the part of those who looked at it from the outside. Inside, the art adorning the walls (in addition to the mosaics of flight there are also mosaics and drawings of terrestrial globes and the constellations) was intended to impress the students of the Aeronautical College as well as guests. Added to this aesthetic value, the building had a pedagogical function, that of pervading the minds of the students who studied in these spaces every day, inspiring the young people who were preparing to become future air soldiers and assigning them a precise identity: heroes and warriors who were contemptuous of danger.

Angelo Canevari and contemporary mosaic

The mosaics were designed by Angelo Canevari (Viterbo 1901-1955). A graduate of the Academy of Rome and an expert in mural decoration and furnishings, in 1931 he joined the futurist movement of Aeropittura and became well-known thanks to his specialization in mosaics, carrying out a number of works in the Foro Italico in Rome. The mosaics for the Aeronautical College of Forlì were assembled by the Luigi Rimassa company of Rome, following Canevari’s drawings, on panels which were then fixed to the walls. The tiles, regular in cut and size (each tile is about one square centimeter), were bound together with cement leaving small spaces in the interstices so as to obtain an effect of notable homogeneity in colour (black and white) and regularity in form. The materials were all Italian: mixed white limestone from Trani, Botticino and Istria and black carbonaceous limestone. Art critics recognize in Canevari’s mosaic work a valorization of two-dimensionality, an energetic contrast between static and vigor, with evident references to the mosaics of Roman villas of the late ancient period.

The history of flight, propaganda and war

The work was located in the entrance reserved for the students of the Aeronautical College. They arrived up a ramp flanked by more black and white mosaics depicting imperial eagles recalling both Roman times and the heraldic symbol of Forlì. After passing through an imposing portal, they would enter the Cortile Italico leading to the classrooms, the gym, the great hall, the reception rooms and the large external square for physical activity. The mosaics are displayed in four sections along the walls of this courtyard, under a portico. The first section features four mosaics dedicated respectively to the ancient myths of Icarus and Phaeton, to the modern genius of Leonardo Da Vinci, to the first military use of aviation in the Italo-Turkish war in Libya in 1911-12 and to the myth of Francesco Baracca in the Great War. To the right of the entrance, the second wall of the portico is dedicated to aeronautical experiments from the 17th century onwards, from parachute prototypes to imaginary flying machines, from hot air balloons to airships, culminating in the invention of the Wright brothers in 1903. Here we may note the first of a number of errors which, out of respect for the work of art, have remained unaltered. The first is the surname of the inventors of the motorized flying machine which, in the mosaic, appears as ‘Wrigt’. Constellations and zodiac signs appear as a background to the drawings and captions.

The ideological fulcrum of the route is the point of contact between the second and third sections. Here there is a declaration attributed to Mussolini dating back to 1909: “The four primordial elements are now in the power of man. We have gone beyond the law that forced us to crawl on the ground. The dream of Icarus, the dream of all generations is becoming reality. Man has conquered the air.” The two sections are separated by a frieze with the Latin motto of D’Annunzio “Memento audere semper” (“Always remember to dare”), and a phrase by D’Annunzio himself which summarizes the “educational” spirit of the mosaics: “Limits to strength? There are no limits to strength. Limits of courage? There are no limits to courage. Limits of suffering? There are no limits to suffering. I say that ‘no more beyond’ is the most outrageous blasphemy against God and man.”

The third wall is dedicated to the feats of Italian civil aviation in the early 20th century: the birth of the air force in Italy, the exploits of Italian pilots (speed, distance, length) and their memorable feats achieved on all continents in the 1920s and 1930s. The ideology of ‘going beyond’ is reiterated at the end of this section. At the end of the section appears the only exception to the exclusive use of black and white: the use of green tiles used to represent three small mice, symbol of the 205th Bombing Squadron “Sorci Verdi” considered to be an elite unit of the Italian Air Force. Next to the drawing is the peremptory slogan: “Living dangerously”. Here too we may note two mistakes. The date of the birth of the air force is incorrect: not March 23, 1923 (as written), but March 28, and the in the illustration of the Atlantic crossing in formation led by Italo Balbo is announced as the “Decennial Air Cruise 1932” whereas it in fact took place in 1933.

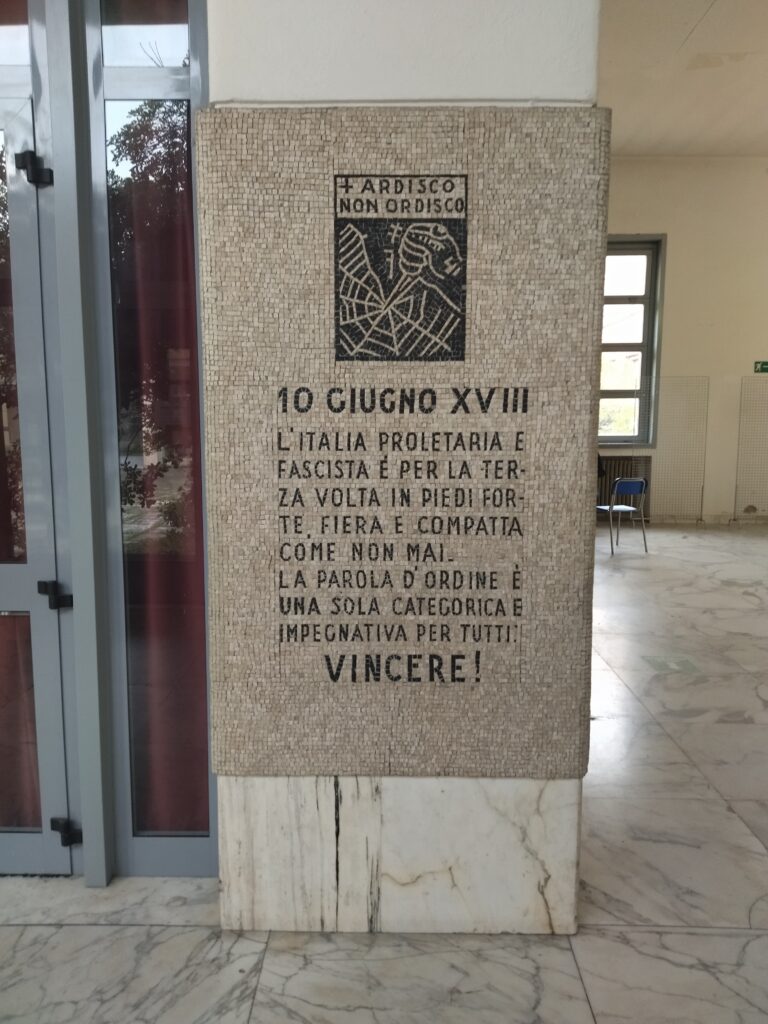

The last section, preceded by a lateral appendix on stratospheric experiments, is dedicated to the military activity of the Air Force between 1940, the year in which, on June 10, the Duce announced Italy’s entry into the war alongside Nazi Germany, and 1941, the year of the inauguration of the Aeronautical College. “Vincere” and “Vinceremo” are the mottos of Mussolini that open and close the section, followed by words praising military action and by depictions of airplanes hurtling through the skies, dropping bombs and engaging in acrobatics. This hymn to supremacy is accompanied by a statistical caption noting the tonnage of the bombs dropped on Greece, the bullets fired, the number of enemy planes shot down.

The final section, then, is a true hymn to war and victory from which the relationship between propaganda and reality emerges with great clarity. The mosaic closes, at the end of the fourth wall of the portico, with a dedication of the Aeronautical College to Bruno Mussolini, flanked by the fascist motto “Credere Obbedire Combattere”.

Art, history and reflection

After Forlì was liberated from the Nazis and the Fascists on 9 November 1944, the building, although damaged by the war, was used by Allied troops to house soldiers stationed in the immediate vicinity of the front line. Since the end of the war, the building has been used as a school for children aged from 10 to 13 and for a time, during the closure for the summer holidays, as the Forlì Trade Fair, before its move to the outskirts of the city. The mosaics are still present, in good condition, tolerated despite the dissonance of their political and historical message: the Fascist interpretation of the challenges of flight, the sympathy for the young Icarus, who in the educational programs of the Republic inspired by the democratic Constitution appeared once more as a symbol of imprudence than of heroism, and above all the panegyric to war. Rediscovered thanks to the activities of the ATRIUM cultural route and initiatives of the Fondo Ambiente Italiano, the mosaics of flight of Angelo Canevari have been relaunched on the national and international level, both for their aesthetic value and for the historical content they exhibit. They are valuable material for students of the history of art and of the propaganda and ideology of Fascism, they can be objects of interest for a critical cultural tourism, and they can constitute a valuable starting point for civic education. As such they are a perfect examples of that “dissonant heritage” that is increasingly an important element in public heritage and historical memory.