By Andrea Tappi and Javier Tébar, Centre for International Historical Studies, University of Barcelona (CEHI-UB)

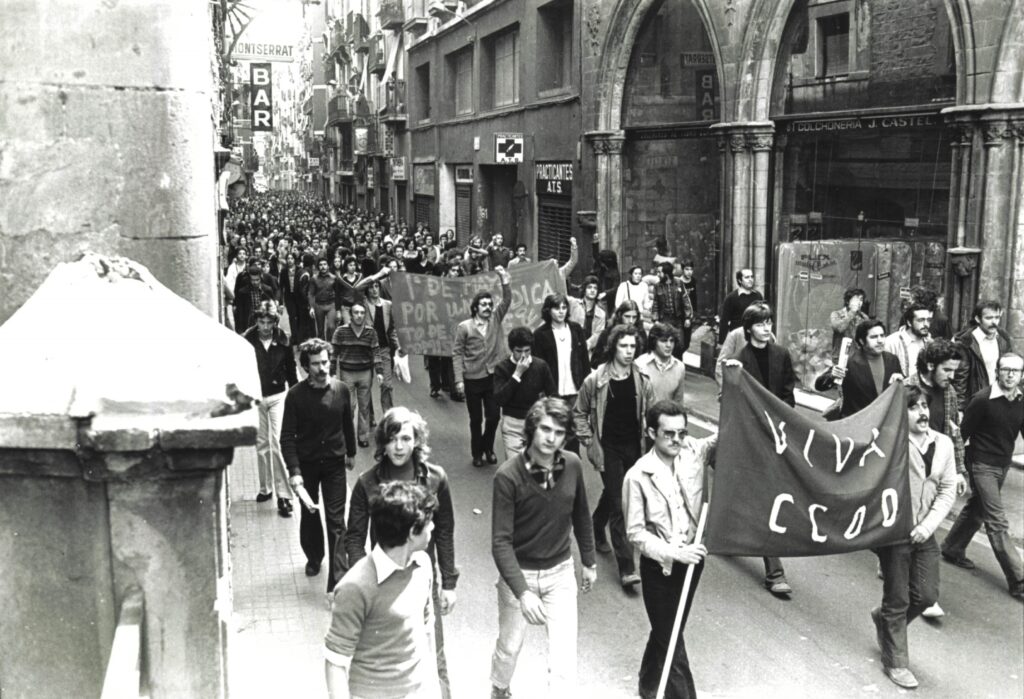

Cover picture: 1. Demonstration of construction workers, March-April 1977, Ferran Street, Barcelona | Arreu Collection, historical archive of the CC.OO. of Catalonia

In the 1970s, the collapse of the Estado Novo (New State) and the Francoist state took place, two of the longest-lasting dictatorships in the contemporary history of Western Europe. This year marks half a century since the military coup carried out by officers of the Armed Forces Movement (MFA) that overthrew Prime Minister Marcelo Caetano, leading to the Carnation Revolution on 25 April 1974. Next year will mark 50 years since the death of the dictator Francisco Franco on 20 November 1975, who became head of state during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and the beginning of the political shift towards the transition to democracy in Spain.

The Iberian dictatorships emerged in the context of the rise of European fascism during the interwar period. Although differing in origin and development, both shared common elements in their forms of governance. Their downfall also occurred within a historical context where the international order of the Cold War was entering the phase of détente. However, this did not mean that the political confrontations maintained by the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, were removed from closely observing the events taking place on the Iberian Peninsula, seeking to influence the respective transition processes through their foreign policies in favour of their geopolitical interests.

Our aim is to first offer a brief historical contextualisation of these recent pasts. Secondly, we intend to comparatively examine the public memory in both countries, with the aim of analysing some of the characteristics of the memory policies surrounding the end of the respective dictatorial regimes and their management within the framework of the processes of transition to democracy: What meaning has been given to them? What stories have been constructed around these pasts? What have been their political uses and the debates derived from them?

Dictatorial Crises and Democratisation Processes: Their Differentiated Contexts

The Portuguese dictatorship, known as Estado Novo, was established by António de Oliveira Salazar in 1933, years after the coup d’état of 1926, which ended the First Republic. This political regime was characterised by strong authoritarianism, nationalism, and corporatism. For over four decades, Salazar and his successor from 27 September 1968, Marcelo Caetano, ruled by suppressing political freedoms and repressing dissent, despite Caetano’s promises of reforms and changes to sustain the regime itself.

The colonial wars fought by Portugal, starting in the 1960s, led the Estado Novo to become embroiled in costly and bloody wars in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau. These conflicts significantly weakened the dictatorship. The economic and human toll of these wars became unsustainable, while internal opposition and growing discontent, as well as international pressure, increased. Thus, the 25 April 1974 coup, led by a group of MFA officers, paved the way for a rapid and complex process of decolonisation, granting independence to its African colonies. This event, known as the Carnation Revolution, was marked by a low manifestation of violence and widespread popular support. The image of soldiers with carnations in the barrels of their rifles became the symbol of this process.

This event not only brought an end to nearly half a century of dictatorship but also set the country on a revolutionary path. Policies aimed at deep social transformation, including the nationalisation of banks and much of the large industry, with some instances of collectivisation, were supported by significant popular mobilisation. The group of MFA officers closest to communist positions announced in March 1975 that the “transition to socialism” had begun within the Ongoing Revolutionary Process (PREC).

The constituent elections of April 1975 gave victory to the Socialist Party of Portugal, founded two years earlier on 19 April 1973 in Bad Münstereifel (FRG), and led by opponent Mário Soares, who had been exiled in Paris since 1970. In the following months, the country came close to civil war, but on 25 November, the attempt of another coup led by groups of officers advocating for further advances in the PREC failed. This outcome would facilitate the socialists, supported by conservative political groups concentrated in the provinces north of the Tagus, to put an end to the political influence of officers close to the positions of the Portuguese Communist Party. Subsequently, the Constituent Assembly, meeting in plenary session on 2 April 1976, approved the Constitution of the Republic, whose Article 1 declared it “a sovereign Republic, based on human dignity and the popular will, committed to transforming into a classless society”.

Spain’s democratisation, like Portugal’s, was not without tensions and challenges. In the Spanish case, the assassination of Prime Minister Admiral Carrero Blanco, following an attack organised by the Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) in Madrid on 20 December 1973, deepened the dictatorship’s crisis. Arias Navarro, the Minister of the Interior, was appointed by Franco as the new Prime Minister on 31 December of that same year. Arias was tasked with designing reform and opening policies, remaining in office after Franco’s death and the proclamation, two days later, on 22 November 1975, of Juan Carlos I as king and head of state. Nevertheless, Arias Navarro’s failure to reconcile reforms with the regime’s survival became evident. On 5 July 1976, the monarch appointed Adolfo Suárez, then Secretary General of the Movement, as Prime Minister. From then on, steps were taken towards a process of political reform driven by groups from the Francoist political establishment, as well as agreements with the main leaders of the political opposition. This led to the general elections on 15 June 1976 which aimed to consolidate a liberal parliamentary democracy. The Spanish Constitution, voted in a referendum on 6 December 1978, which put an end to the Fundamental Laws of the regime that emerged victorious in the civil war, stated in its Article 1 that “Spain is constituted as a social and democratic State of law, which promotes as the highest values of its legal order liberty, justice, equality, and political pluralism. National sovereignty resides in the Spanish people, from whom the powers of the State emanate”.

The end of both dictatorships is often included in what is termed the “Third Wave of Democratisation” (Huntington, 1994), conceived as negotiated processes for the establishment of liberal-democratic systems. This phenomenon had an initial impetus that, in addition to Portugal and Spain, included the fall of the Colonels’ dictatorship in Greece, which occurred on 24 July 1974. However, this democratising wave would extend until 1991, affecting transition processes in Eastern Europe with the Soviet collapse, as well as those experienced in the Southern Cone of Latin America.

Nonetheless, the political and social rupture that occurred in Portugal would not fully align with this model nor would have distinct characteristics that should not be overlooked. In fact, systematic comparisons are often made between the Portuguese Revolution and the Spanish Transition, portraying the latter as a model process due to its combination of moderation, reconciliation, and negotiation, contrasted with the radicalism, violence, and rupture symbolised by the process initiated on 25 April in Portugal. In the effort to group and compare the Portuguese case with Spain’s process of democratic consolidation, it is often overlooked that the Portuguese transition “was a post-revolutionary (or even anti-revolutionary) outcome.” This revolution, with openly socialist goals explicitly stated in its constitutional text, saw its political and social model rapidly evolve towards a traditional liberal-democratic direction, aligning with the liberal-conservative turn in the West in the late 1970s (Loff, 2024).

In conclusion, the paths to democratisation were different. Both countries certainly consolidated democratic systems that endure to this day and achieved full integration into the international community. However, neither of these transitions was inevitable or pre-planned, nor did the political actors of the time necessarily see it that way, given the uncertainties of these processes. In Spain, a negotiated transition was chosen, which was not solely the result of elite negotiations but was also shaped by pressure and protest from the streets, which intensified in 1976. In Portugal, the process was initiated by a popular revolution, particularly led by groups of young officers from the colonial army, influenced by revolutionary ideas.

Traumatic Pasts, Shifting Pasts: Battles Over Public Memory and Its Management

Unlike Spain, where the memory of the dictatorship remains a markedly divisive issue, Portugal has, until recently, seen greater consensus around the condemnation of the Estado Novo. In this case, the regime’s repression and limitations have been widely acknowledged, and there is a notable effort to educate new generations about this dark period in Portuguese history. This is because the processes of reconciliation and justice have differed between the two countries. In Spain, the transition was largely negotiated, which led to a “politics of forgetting” that avoided prosecuting those responsible for Francoist crimes to facilitate democratic consolidation. This has led to current debates on historical memory and the need for justice for the regime’s victims In contrast, the Carnation Revolution in Portugal allowed for a more open process of justice and reconciliation. Although elements of forgetting were present, the consensus around condemning the Estado Novo has been more pronounced.

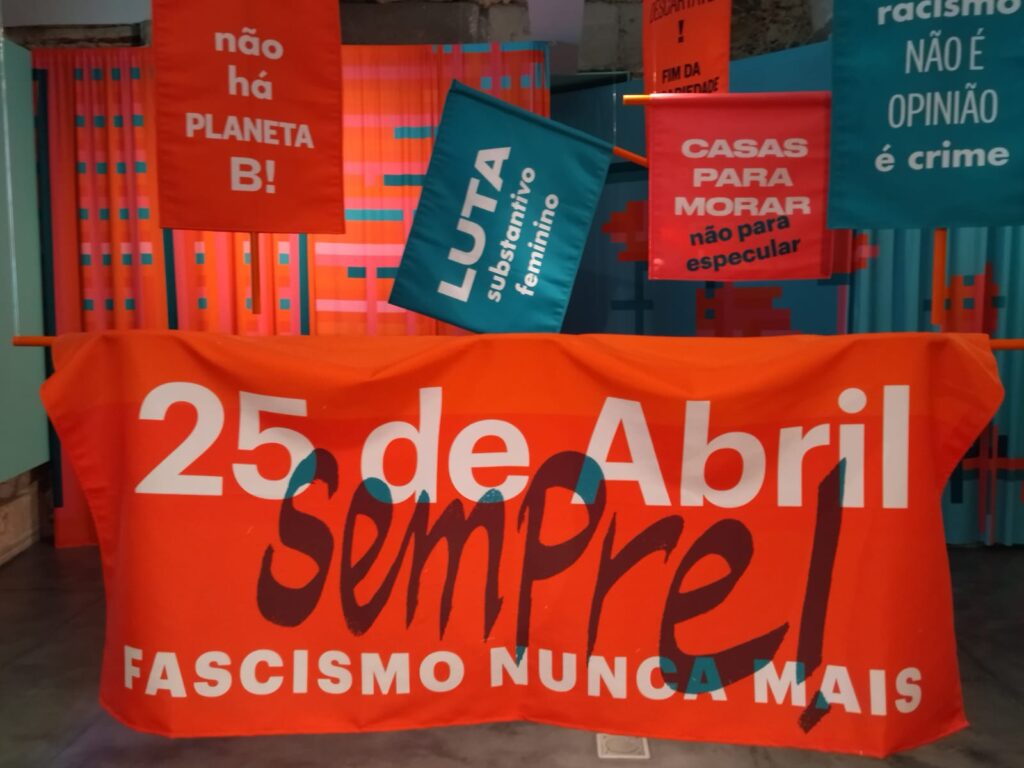

Moreover, the memory of the Portuguese Revolution has been widely celebrated every 25 April. The country commemorates Freedom Day, marking the end of the dictatorship and the beginning of democracy. This date is a moment of reflection on democratic achievements and a tribute to those who fought for freedom. It has become a central element of Portuguese collective memory, with commemoration and ritualisation not only serving to remember the past but also to affirm democratic values in the present. In contrast, in Spain, this symbolic calendar, which includes 6 December 1978, the date of the Referendum for the approval of the Constitution, though celebrated annually as a public holiday, is difficult to place on the same level of social significance and public celebration.

However, the legacy of the Carnation Revolution remains complex and ambivalent in the country’s collective memory. In the early years of the political transition, anti-fascist memories were dominant. The political actors of the time promoted a narrative of breaking with the dictatorial past, but also of subversion and transformation of the political and social order. From 1976, during the consolidation process, under constitutional governments, a conservative and counter-revolutionary discourse began to develop, seeking a homologation that aligned with the illusory desire to view the Portuguese case as the start of a third wave of democratisation. This was the result of a discourse about a country that began to deny the revolutionary moments of its democracy as foundational, instead portraying them as a prior, distorting force that had to be corrected (Loff, 2024).

Over the years, the memory of the Revolution (1974-1975) has been the subject of historiographical debates and historical revisionism. There have been reinterpretations that reflect the changes in the country’s political and social context. This battle for memory in the public sphere was clearly expressed on the 20th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution in 1994. The uses of that memory in different historical contexts have allowed it to be instrumentalized to serve contemporary political aims. Today, this issue remains vital, not just as a memory of the past, but as an active resource that influences current Portuguese politics. In fact, it has become an ideological battleground. Debates about its meaning and consequences have reflected broader political divisions in society. While the left has generally celebrated the Revolution as an emancipatory and progressive moment, certain sectors of the right have sought to minimize its impact or reinterpret its achievements, portraying it as a chaotic interruption in national history.

Nonetheless, the memory of the Revolution and the 25th of April has played a significant role in shaping national identity, rooted in the values of freedom, democracy, and social justice. School textbooks and educational programmes have been key tools in conveying official narratives about the Revolution. However, these narratives can vary and sometimes face tensions between a more critical view and a more celebratory interpretation of events. This suggests that national identity is not monolithic and is subject to reinterpretation and dispute, especially in times of political or social crisis. For example, during the austerity years and economic crisis at the end of the 2010s, revolutionary memory was invoked both by those advocating for redistribution and social protection policies and by those criticising state intervention and pushing for neoliberal economic reforms.

In Spain, the political instrumentalisation of memory and the myth of the country’s transition to democracy has also occurred. Over the years, Spain’s Transition has consistently been presented as “exemplary,” even as a “model” to guide political change processes that took place in the 1980s and 1990s. This Transition is considered a legacy upon which the official memory legitimises Spanish democracy itself. However, from 2011 onwards, amid the social damage caused by the Great Recession of 2008 and the rise of the 15-M movement in a new political cycle, a narrative questioning the entire Transition process gained strength.

As a result, we now face a series of narratives and representations about the Transition, accompanied by evaluations, judgements, and proposals on how to manage that past. Although some of these narratives are often presented as new, they all have a long history. This brings us to the political uses of the past in constructing the narratives around the Spanish “Transition”. Its “rewritings,” linked to the dichotomy of “model/counter-model”, or, seen another way, the “myth/anti-myth” dynamic, have prevailed and have not necessarily contributed to a better understanding of the historical significance of that period, which could strengthen democratic values and culture.

In education, the school narrative about the Transition in Spanish secondary and high school textbooks connects it to the paradigm of modernity. In other words, the end of Francoism and the establishment of the democratic regime are confined to a few decisive years, during which Spain’s long process of economic, political, social, and cultural modernisation, which began in the 19th century, is said to have inevitably triumphed. This overshadows the violent conflicts of the 20th century. It can be argued that the narrative of the Transition in classrooms is a product of this same historical process and takes on a functional role, aimed at transmitting, in a reconciliatory and uncritical manner, certain identity values and the exaltation of national unity.

Recently, when reflecting on concepts like memory – both individual and collective – the value of witnesses, reparation, and the question of whether or not to forget, historian Álvarez Junco referred to a “dirty past”. In Portugal, the annual celebration of the Carnation Revolution and the condemnation of the Estado Novo reflect a relatively broader consensus on the importance of remembering and learning from a “dirty past”. However, in Spain, while the transition to democracy was achieved, “many things were left unresolved”, something for which the same author argues that one should “defend the Transition with reservations, without triumphalism” (Álvarez Junco, 2022). This is because, in the Spanish case, the struggle for recognition and reparation for the victims of Francoism remains an unfinished issue. After the government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero passed the so-called “Historical Memory Law”, Law 52/2007, the Spanish authorities, under Mariano Rajoy’s government, faced a normative challenge in 2014 regarding democratic memory. This came from Pablo de Greiff, the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation, and guarantees of non-repetition, and from the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances. In their two reports, following a visit to Spain, de Greiff highlighted the need to implement a policy of Truth, Justice, Reparation, and Guarantees of Non-Recurrence. These are the principles of transitional justice, endorsed by international law, and applied in countries with a traumatic past marked by mass human rights violations.

4. Workers’ occupation of the SEaT car factory in Barcelona on October 18, 1971 | Photographic collections of the historical archive of the CC.OO. of Catalonia

The approval of the new Democratic Memory Law in October 2022, by the coalition government led by Pedro Sánchez, was an acknowledgement of this problem. It also provided an opportunity to move forward, albeit with difficulties, in a country where high political polarisation and the so-called “culture wars” spurred by the far right do not provide the best environment to emphasise the importance of remembering and learning from a “dirty past”.

Conclusion

The memories of this period remain a vital and often controversial subject. The range of issues arising from the proposed comparison would reveal the nature of collective memory as inherently a field of conflict between different memories, as well as its impact on contemporary politics and society. These debates invite reflection on their importance and raise questions about how narratives of the past can and do shape our present and future.

Lastly, it is worth adding that these historical processes and their memories teach us about resistance, the struggle for freedom, and the complexity of political transitions. In other words, they remain relevant today, not only for understanding the past of both countries but also for reflecting on the current and future challenges and threats to the defence of democracy and human rights worldwide.

References

José ÁLVAREZ JUNCO (2022), Qué hacer con un pasado sucio. Galaxia Gutenberg, Barcelona.

Samuel HUNTINGTON (1991): “Democracy’s Third Wave”, in Journal of Democracy, (Spring), pp. 12–34.

Manuel LOFF (2024): “A Revolução portuguesa (1974‑1976), um modelo específico de democratização no século XX”, Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, 133, pp. 13-34. DOI: 10.4000/11pr1