Thomas Reider (scriptwriter) and Bernhard Steinmann (filmmaker)

Sbout the movie “Great Freedom” (2021)

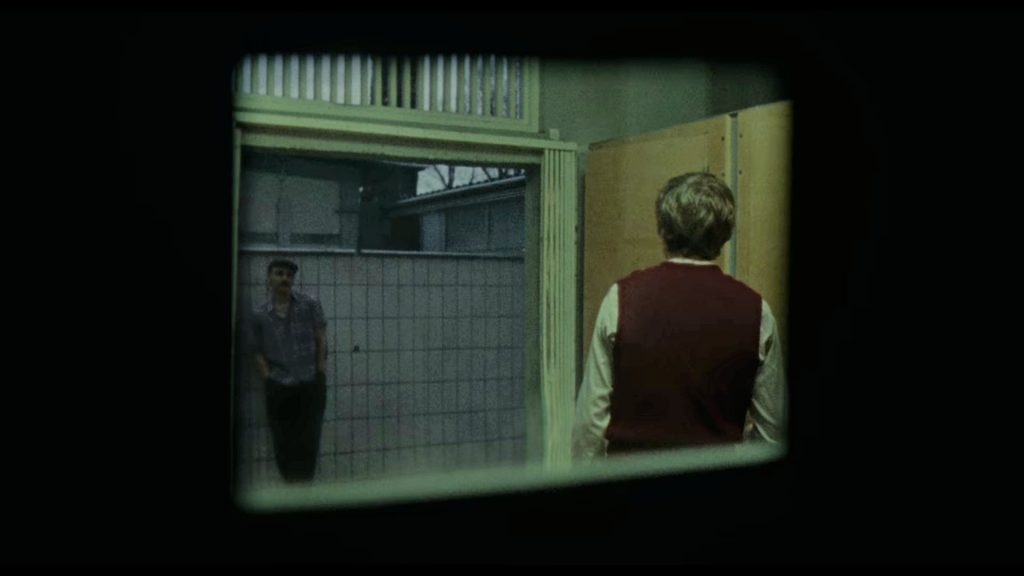

Cover image: Controlling Eye – Solitary confinement for a gay man in total darkness. Still from Great Freedom (2021)

“A man must dream a long time in order to act with grandeur,and dreaming is nursed in darkness.”

Jean Genet

For 123 years, Paragraph 175 banned homosexuality in Germany. Those convicted were sentenced to prison terms of up to ten years. Surveillance, blackmail, denunciation, torture, and murder were daily threats. In Nazi concentration camps, gays were a special category, being made wear the insignia of a pink triangle (Rosa Winkel in German). The “liberation” by the Allies in 1945 did not bring freedom for homosexuals. The National Socialist (tightened) version of Paragraph 175 continued to apply without restriction. Thus, after the end of the war, gay concentration camp prisoners were even transferred directly from the concentration camps to prison, to serve their remaining sentence. “Pink Lists” (Rosa Listen in German) from the Third Reich continued to be used and helped to track down the “perverts”. The infamous Paragraph 175 gave generations of gay men a name: 175! was synonymous with homosexual. The total ban on homosexuality remained in place until 1969. But it would take another 25 years for Paragraph 175 to completely disappear from the German Civil Code in 1994. This paragraph did not continue to exist out of oversight but was, over the decades, re-examined, recertified and reconfirmed. During the post-war years, 100,000 men were brought to trial in West Germany alone. Paragraph 175 allowed authorities to intercept and confiscate love letters and submit them to court as evidence and to install cameras behind mirrors, encroaching on the privacy of these men, revealing their intimate lives, and exposing extremely personal details to the public.

A scenario reminiscent of George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984.

Faced with the impossibility of socially accepted sexuality, we homos, sodomites, urnings, fags, queers, psychos, heretics, asocials, perverts, or however we were called throughout history, sought alternatives. We met away from the controlling collective eye in the bushes of public parks, criss-crossing the nocturnal darkness in search of brief moments of intimacy. We added a transgressive sexual layer to established utilitarian architectures. So public restrooms would always satisfy a broader range of needs, and offer different kinds of rests. In the United Kingdom, toilets used for sex are called “tearooms”, “cottages”, “beats” or “bog-houses”. In Germany, the name “Klappe” is common, while in Vienna men meet in the “Loge”. The diversity of names for those places of desire shows what importance they represent for “outcasts” worldwide.

In times of criminalized love, homosexuals have become experts in stealing moments of privacy and discovering cracks within society that offer the possibility of a sexual encounter. They take refuge in the city’s darkness and anonymity, because the public sphere paradoxically offers more privacy than their private ones.

Gays got used to being given wicked names and to live and survive in wicked situations. The definition problem was followed by the challenge to find a place to love. In the absence of options provided by society, these were abysmal, underground and hidden places. People whose sex had been persecuted, forbidden, and brought into the public eye over the centuries, had no choice but to seek out places within society, but beyond the bounds of society’s perception.

The quest for sexual encounters in public spaces is called “cruising”. Despite being historically characterized by dependant relationships, over the centuries it has established itself as an equal, democratic, intimate encounter outside the norms of mainstream society. Unnoticed by the general public, a homosexual underground emerged that met the need for closeness and intimacy. The search for confirmation of not being alone with one’s desires and needs, one’s love and lust. Men would meet in secluded parks, in public toilets, in theatre boxes and the last row in a cinema. Mostly under the cover of the night.

The historical circumstances provide an understanding of the need for these sexual encounters between men: fast and fleeting, anonymous and in the dark. Because their actual private spaces were disqualified on account of social restrictions. What in the general understanding would in fact have to be qualified as public sex was thus one of the few forms of possible privacy within a hostile society. This also led to a quickening of the actual sexual encounters, because no one wanted to be caught, given the threat of punishment – from imprisonment, internment, loss of honour, stigmatization, humiliation, to death. In light of this fact, the superficially easy separation of the “private” and “public” spheres appears to be a shaky construct of a fearful society, which further confirmed the already attested perversion in the cruising men.

A darkroom is a place for developing film material. A darkroom is also a room that a persecuted community built, filled and claimed for itself. The history of this room, specifically dedicated to sexual encounters, is closely tied to the history of emancipation of modern homosexuality itself. Emerging from the margins of post-war America, this enchanted space took root in the heart of the homosexual underground, waiting to move towards the light. Despite the most strenuous attempts, the basic need for sex could be forbidden, but never eradicated.

Informal and illicit encounters in the darkness of the cities also gave rise to qualities to which people thought to pay tribute in a fetishized way even after repression had ceased. All these secret spots became the blueprint when it came to hosting the public gay sex culture in darkrooms.

Turning a swear word into a self-designation and elevating symbols of oppression to a fetish is both a coping strategy and one for self-empowerment. A darkroom can therefore be seen as the epitome of a freedom movement of all the battered gay generations who had been robbed of their youth and are old enough by now to appreciate the dimmed light. The stolen loves, the forbidden lives, all the offsides, all the banished identities gather here in the darkness of this museum-like space of contemplation. Thanks to darkrooms, “cruising” has not only been given a structural framework, but also an interactive memorial space of the history of involuntarily stolen, public sex culture, assembling a broad repertoire of elements and situations that reference persecution and emancipation.

With the first structural manifestation of darkrooms as “blackrooms” within the American gay biker scene of the 1950s, numerous future constants of these sex rooms were established. The black paint, their raw aesthetics and the darkness can be directly traced back to their predecessors. The gay biker gangs represented an antithesis to the then-common stereotype of the effeminate homosexual. A new gay ideal of masculinity was brought into being: you no longer dressed up as a woman just because you wanted to get fucked. You posed as a tough guy in black leather and faced society with a humming machine under your ass. A wild reputation preceded the bikers and the new style was both a rejection of “weakness” and an affront to homophobes.

The associated masculine self-image of homosexuals coincided with a time of extreme prudishness. Post-war American society was less committed to individual self-determination than to the goal of a homogeneous, morally and ethically superior society. The American Dream had precise ideas for everyone, and queers didn’t fit in.

The development and dissemination of the first “blackrooms” took place at a time when homosexuality in America was not only stigmatized but also a crime. The meticulous methodology of this obscure persecution (spying, surveillance and decoy tactics) thereby fulfils the definition of perversion far more than the scenarios observed. The same applies to Europe. In Germany, the police would hide behind mirrors with their cameras rolling. Filming the cruising men and arresting them. Directly from the toilet to jail. From one shithole to the other. The question remains: Who’s the pervert here?

We all spend the first nine months of our existence in darkness. The last sense to form is sight. Modern cities are brightly lit at night. To take people out of anonymity and facelessness as well as to tame the potential for aggression. The fear of darkness is one of man’s most common phobias. On the other hand, scientists already presented studies in the 1970s that indicate the opposite: Mary and Kenneth Gergen took eight strangers and shut them inside a darkroom for an hour. What happened next? Infrared-cameras would show: People were constantly moving around, but the conversation diminished after the first 30 minutes, paving the way for other forms of interaction: about 90 per cent of the participants touched each other intentionally, with half of the participants hugging each other in the dark. This study was conducted in 1973. What would be observed in such an experiment today?

The bedroom is one of the few places where the absence of light is considered positive. Apart from the cinema, our society knows no such dark meeting places. At the cinema, all attention is focused on the screen, whereas in the darkroom it’s focused on the people present.

Thomas Edison and William Dickson make one of the first movies ever, featuring two men dancing with one another, and a third guy playing his violin. That was in 1895.

Two years later, a young doctor named Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (WhK) in Berlin, the world’s first movement for homosexual rights. The doctor and his students chose a catchy motto: Per scientiam ad justitiam (Latin for “Justice through science”). With scientific research into homosexuality as the basis for media-effective, political actions, they endeavoured to achieve legal progress. This was followed by extensive publishing activity, not only of scientific papers, but also of simple educational pamphlets, of which almost 100,000 (by 1914) were sent specifically to newspapers, civil servants, lawyers, doctors, university professors, church dignitaries and teachers.

It is amazing how freely and unhindered the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee was able to operate in Germany. Similar journalistic activity would have been unthinkable in Britain, for example – there, around that time, the trials surrounding the famous writer Oscar Wilde were making waves. In France, on the other hand, homosexuality had already been decriminalized and censorship was relatively mild. The portrayal of homosexuality in literature was often direct and blunt. Nevertheless, the discourse of academia and homosexual subculture was non-existent, or characterized by ignorance.

Hirschfeld succeeded in winning over the leadership of the Social Democratic Party to support a petition against Paragraph 175. The proposal was considered in the Reichstag in 1898, but failed. Undeterred, the WhK continued its propagandistic activities. Dozens of public lectures in Berlin and other German cities were held to inform the people. They would collect statistics on the proportion of homosexuals in the German population. This earned Hirschfeld criminal charges for defamation.

In the early 20th century, Berlin was something of a laboratory for sexual deviance. The media presence reinforced Berlin’s reputation as a gay Eldorado. In Italy, people used “berlinese” synonymously with homosexual, the French knew a “vice allemand”, and the English agreed on “German custom”.

In 1919, Hirschfeld opened his Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin, the first institution of its kind in the world. This Institute was dedicated not only to providing medical and psychological counselling to both homosexual and heterosexual people, but also sought to further establish sexology as an academic field of research.

That very same year, Magnus Hirschfeld and the Austrian film director Richard Oswald also released the first gay movie in film history: Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others). An older musician is blackmailed by a younger hustler. At some point, the musician refuses to pay. The hustler turns him in, and the homo ends up in court for violating Paragraph 175. In the ensuing court proceedings, Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (who plays himself) makes a two-minute plea (to be read in white on black) for acceptance and tolerance that defies all conventions. The blackmailed gay man is sentenced according to Paragraph 175. The resulting shame will lead to his suicide.

In 1920 – founding of the NSDAP (National Socialist Party) in the Hofbräuhaus in February – the film was already banned.

It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives (Nicht der Homosexuelle ist pervers, sondern die Situation, in der er lebt) was the programmatic title of Rosa von Praunheim’s film that gave impetus to the German student gay movement of the 1970s: “Out of the toilets, into society” was the new battle cry. The emphasis was on visibility and attacking bourgeois society. The so-called “homophiles” of the post-war period were said not to have the balls for this. Maybe they really had lost them as a result of “voluntary” castration under Hitler. The homophile movement of the 1950s and 1960s had until then consisted of men who had suffered persecution and terror and continuous criminalization on their own bodies.

History is full of black holes. Great Freedom (directed by Sebastian Meise) is full of black holes. The pitch dark solitary confinement cells, which in prison jargon are called “the hole”, act as wormholes into different times zones: 1945 – the war is over, but not for homosexuals; 1957 – love is banned; and 1969 – first men land on the moon and homosexuals still land in jail.

“I’ve been on the run all my life!” Such lines sound edgy in a prison movie, but actually, they are the brutal reality. Even today, with homosexuality being punished by repression or death, depending on geography. In one out of three countries, homosexuality is still illegal.

The film’s protagonist Hans Hoffmann is a cipher. A synonym for the persistence of the oppressed. Hans is the fusion of countless real persons who gave their lives in cells and concentration camps and who also gave their voices in diaries, books, interviews, or their bare existence.

Worldwide, the suicide rate among adolescent homosexuals is as high as ever.

Because freedom is not only something filigree, but vital.

Literature

Beachy, Robert (2015). Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity. New York: Random House

Betsky, Aaron (1997). Queer Space. Architecture and Same-Sex Desire. New York: William Morrow and Company

Dobler, Jens (2010). Von anderen Ufern: Geschichte der Berliner Lesben und Schwulen in Kreuzberg und Friedrichshain. Berlin: Bruno Gmünder, 2003

Gergen, Mary; Gergen Kenneth (1973). “Deviance in the Dark” scientific study (In Psychology Today, October 1973, New York, pp. 129-30)

Gove, Ben (2000). Cruising Culture, Promiscuity, Desire and American Gay Literature. Edinburgh: University Press

Hirschfeld, Magnus (2001 [1914]). Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter

Micheler, Stefan (2010). “…und verbleibt weiter in Sicherheitsverwahrung – Kontinuitäten der Verfolgung Männer begehrender Männer in Hamburg 1945-1949”. (In: Ohnmacht und Aufbegehren. Homosexuelle Männer in der frühen Bundesrepublik, Hamburg: Männerschwarm)

Steinmann, Bernhard (2016). “Darkroom – eine Raumgeschichte vom Abseits zur Sehenswürdigkeit”. Diploma Thesis, Technische Universität Wien

Zinn, Alexander (2015). Das Glück kam immer zu mir” Rudolf Brazda – Das Überleben eines Homosexuellen im Dritten Reich. Frankfurt/New York: Campus

Films

Anders als die Andern / Different from the Others (1919). Directed by Richard Oswald

Un chant d’amour / Song of Love (1950). Directed by Jean Genet

Nicht der Homosexuelle ist pervers, sondern die Situation, in der er lebt / It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives (1971). Directed by Rosa von PraunheimGroße Freiheit / Great Freedom (2021). Directed by Sebastian Meise