Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk

Historian

In 1989 and 1990, two historical events took place that have been much discussed, debated, and argued over. The 1989 Peaceful Revolution brought down the SED dictatorship in East Germany and the two Germanies were united in a new democratic state the following year. While these events brought an end to the post-war period in Germany and ushered in the New Europe, their overall importance in world history is a matter of conjecture. We do not yet know for certain whether future historians will treat any events as decisive caesuras of global, or perhaps just European importance, whether we are talking about the 1973 oil crisis, the 1989/91 anti-communist revolutions and the collapse and dissolution of the Soviet Union, the 2001 terrorist attacks against the twin towers, or the 2020/2021 Coronavirus pandemic. Caesuras help to map, order, clarify, and arrange history in order to be able to relate past events, freeze-framed as history, in a structured way. Large-scale caesuras, such as those above, provide a framework, which internal caesuras, depending on the issue under scrutiny and the methodological approach, help to justify. These “major” caesuras follow political-historical considerations, but they are “porous” because political-historical caesurae almost never have an immediate impact on economic, cultural, mental, and social structures, processes, and phenomena. Societies are often far more sluggish and often don’t change in lockstep with these epoch-changing events. This happens only in exceptional cases and cannot even be shown conclusively to have happened in Germany in 1945, 1918, or 1933. In the case of 1989/90, research has so far not even problematized the caesura, but it seems obvious that the fall of the Berlin wall on November 9, 1989, and monetary union on July 1, 1990, when the West German Mark was introduced in the GDR, had such a profound impact on the lives of every single East German — monetary union even more so than the fall of the wall — that these two events do indeed represent a major caesura. Most East Germans were not directly involved in the fall of the wall — it fell whether they liked it or not — but both the fall of the wall and the monetary union on July 1, 1990 were welcomed, even applauded, by an overwhelming majority of East Germans. According to the narrative, the March 18 elections to the Volkskammer (former East German parliament) triggered a headlong rush to eventual union, with about three-quarters of East Germans voting for monetary, economic and social union and the introduction of the West German constitutional system, including representative democracy. What this three quarter majority did not choose, did not even begin to demand, however, were the dramatic consequences of this decision. That is what this essay is about.

(From Here and There), filmed between Munich

and Berlin in 1989 and 1990 and co-directed by

Margit Ruile and Stefanie Kremser | Stefanie Kremser

Reunification ensued in line with a classic pattern of “othering”. The rules established in the dominant space, the Federal Republic, were endowed with universal validity and were transformed and applied to the “empty space” of East Germany, as if nothing had existed there, no one had lived there, and as if there were no structures or experience there. The space was not empty, of course, but it was treated as such. This kind of approach can only work if what existed there before is reconstructed in two ways. The two spaces are stuck together as if everything in the new space — from North to South, from East to West — is the same; there are no differences. This has two major effects: On the one hand, there are those who resisted the old system until 1989, who are used to legitimize the new system, and on the other side of the divide, there are those who represented the old system and now continue to cling to it. They are viewed as living proof of the need to delegitimize all of what had occurred previously. Those caught in between the two groups are simply homogenized. This is exactly what happened in East Germany from 1990 onward. Those in power drew up one homogenized space, East Germany, and one homogenized population, the East Germans.

To appreciate this it is necessary to understand that unlike West Germans, East German are seen as East Germans practically everywhere in the world. West Germans are defined as such only in East Germany, nowhere else. No one in Hamburg would think of calling someone from Munich a West German. In linguistic terms, West Germans only call themselves West Germans, somewhat unthinkingly, when they are in the East; East Germans, on the other hand, are called East German everywhere.

Why is this the case? First, there is a simple, instrumental reason. If one wishes to transform a country’s entire economic, monetary, and sociopolitical system overnight — albeit in line with the will of the people living there — then in principle one has to treat the area as if nothing had existed there before. History teaches us that this is not at all unusual; these processes have taken place in numerous places, usually with dramatic consequences. The unique situation in East Germany, however, was that three quarters of East Germans apparently sought this punishing transformation process, since they had voted for it. What they did not want, however, were the consequences.

Ongoing post-amputation phantom pains

The debate in both academic and public arenas is as follows: Many apologists for the way in which reunification transpired argue that everything that followed had been chosen by the East Germans. I would reject that argument: what the East Germans voted for on March 18 was the rapid transfer of the West German system to the GDR, which still existed at the time. Above all, they wanted the West German Mark. But to infer from this that they could also foresee, let alone wanted, all the consequences that resulted is absurd. Nobody would have wanted these consequences. Nevertheless, they have been justified again and again by the need to homogenize space and society. If one followed this reasoning to its logical conclusion one could implement and justify almost anything in terms of power and domination.

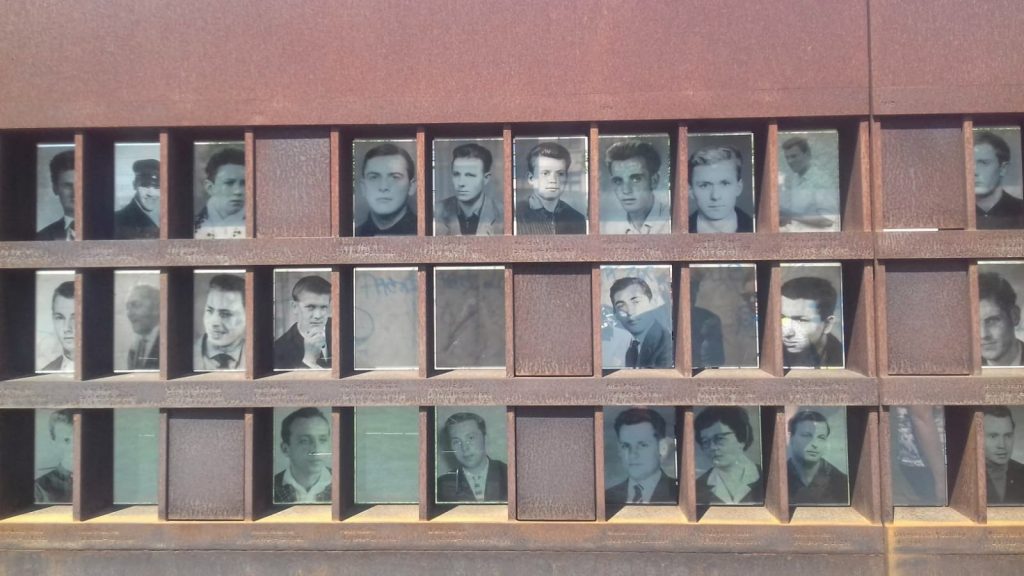

If one takes a closer look, once can see that over the past 30 years, the debate about German reunification has always focused on political and financial issues: What happened economically? What happened politically? How much money was paid out? But I would argue that in addition to the enormous financial resources invested, there were also dramatic social costs to reunification. Millions of people lost their jobs, millions had to retrain, and many people in the East have been dependent on state support ever since. Whole age cohorts have been declared superfluous to requirements.

Almost every family in the former GDR has been affected. An entire society underwent a massive upheaval within a very short time. While West German society took almost 25 years to develop from an industrial society into a service society, one could say that East Germany just had one night to undergo the same process.

Loss of cultural positions

This brings me to an actually much more interesting point, one which continues to be important and which is usually ignored in more positive assessments of unification. People lost not only social positions, or gave up political positions at any rate; above all, they lost cultural positions. They have been unable to regain their cultural positions, and this loss still causes pain today, much like that suffered after an amputation.

To understand this, one must realize the following: The GDR was a society based around work, as was the Western world until the late 1960s and early 1970s. But society was quite different in the GDR. Work was not only an integral part of everyday life in the GDR; a person’s entire social and individual private life was organized around work and the institution one worked in. That meant everything making up a society — healthcare, vacations, childcare, sports, cultural, and art clubs etc. — everything was grouped around the workplace. So you not only worked together, you went on vacation together, fell sick together, and got well together, and your children went to summer camp together. People did sports together, went to reading groups together, and did amateur dramatics together. And of course, they fell in love in these contexts also.

It must be stressed that the system had largely collapsed and the shock of the transformation began even before monetary union in 1990. This happened because all companies, combines, and state institutions were quick to dock non-productive areas from their structures in order to become more flexible and to reduce costs. The much lower labor productivity in the GDR was partly due to the enormous size of the non-productive areas, but this was because they included not only bureaucracy, but also the cultural, sports and leisure areas.

The collapse of the institutions completely changed social existence in the East. This, however, was met with total incomprehension by those who had taken over overnight — the elites from the West — because they had no experience of this in their own “lifeworld.” So what is the situation now?

It is clear to see that there was a major clash between two entirely different ways of life. One might argue that East Frisians in Northern Germany also have very different lifestyles from Swabians in the South, but that doesn’t constitute a problem. But they are not living in an area in which something is being built from scratch, which those living there have no experience of. One might also wonder whether this radical reconstruction was absolutely necessary. Unlike the three quarters of East Germans who chose this path, I didn’t vote for it at the time because it was clear to me that there would be a clash and because I wanted union to be slower, more cautious, with both sides on a more equal footing, and the East more assertive and less submissive. If I was assertive personally, don’t I have a right to expect society to be assertive too? But the majority didn’t agree with me, and in one respect, there really was no alternative at the time. At least that’s how it was presented, and I still believe that there was ultimately no alternative. And I can be fairly relaxed about it, because, unlike many others, I only gained and really lost nothing, absolutely nothing, through the downfall of the communist dictatorship. Only I was not deceived about the West, so I could not be disappointed subsequently.

But the people wanted the Deutschmark, and of course the Deutschmark didn’t come free; it could only be granted if people were willing to accept all the institutions and legal systems that guarantee the Deutschmark’s stability. Nothing else would have worked. The legal and economic institutions and the welfare state could only be built up reasonably smoothly and function reasonably well from one day to the next if people who were familiar with the institutions took charge of them. This meant the movement of elites from West to East.

Movement of Western elites to the East

The tens of thousands who came from the West and took control of the institutions set the rules. Since the vast majority of people who worked in the East had a completely different social- and cultural-political background, this clearly led to major conflicts, because the rule-givers naturally drew on their own experience, which they then applied to the population. In general terms, the West said, “you Easterners must become like us Westerners” (at least, the way we see ourselves). And the West Germans did not treat East Germans as equals; they did not come to the East as workers, but as owners, directors, and superiors. Westerners were the bosses, Easterners the subordinates. This is a structural problem that is still with us today.

That was the essence of the process. It is well-known from general business research what these power relationships imply. The culture of mergers tends to involve one side becoming like the other, or at least becoming what the other thinks it is. There may be political reasons for doing this, but culturally, the approach is a disaster.

This is also reflected in the completely naïve demand “to tell each other our own stories,” a demand that has been repeated for over three decades. What lies behind the demand is not that everyone from some town in the West, Wanne-Eickel, for example, should tell me their story in East Berlin. Rather, it tends to mean that the “newcomers,” that is, the East Germans, should tell their stories to the majority in the West. This should also be the case when someone from Paderborn in the West goes to Riesa in the East, but newcomers to the East were not expected to tell their story; those who had lived there all their lives had to tell their stories to the person from Paderborn so that the latter would accept it — the reverse was not true, it was a matter of complete indifference. The West, i.e. the majority, listened, took careful note, and then approved or disapproved: You are one of us or not.

In other words, it was necessary to tell one’s story, so that the majority partner could decide who was accepted and who was not. It was not about mutual understanding and getting to know each other, it was a one-way street, and has been right from the outset. This sounds like a master plan, of course, but there was no such thing. These are social and cultural processes that simply belong to the discourses of those in power, and ultimately, in power relationships themselves. One side says what’s what and the others have to follow suit. Those who have the money have the power. It’s as simple as that; it’s not necessary to go back to classics from the 19th century to understand the situation.

This led to numerous conflicts on every level. Tensions like these exist everywhere in societies in which different subgroups clash and one subgroup exercises power and domination, but why has the discourse on German union been as it has over last three decades? In other words, why has a broader critical discussion about the course of unification only occurred in recent years? I believe there are three main reasons why this has been the case.

Critical voices unwelcome

The first reason is perhaps the most important. What is probably difficult to recall today is that anyone who was critical of the unification process in the 1990s was more or less considered a supporter of the post-communist SED-PDS and thus an apologist for the defunct system. Before 1989, people in the West also often said to those who were critical of the system in any way, “Well, go to Moscow, then!” and many who have been critical of the reunification process since 1990 have been met with a similar response. They were suspected of belonging to the defunct system and of wanting to defend its virtues. I also took this attitude for a long time, simply because I was glad that the GDR regime had been brought down and I clearly and unequivocally rejected the SED-PDS in the 1990s.

A rejection of criticism has persisted until today amongst many older and more conservative contemporaries. This can be seen in the way some critics have viewed my book “Die Übernahme” (The Takeover) and the way they have criticized me personally. Some have declared that I am an apologist for the GDR, which is quite absurd. After all, this is not the first book I have written as a historian — hitherto my reputation has been quite the opposite. Moreover, this attitude has much to do with suspicion of anybody whose analysis of the unification process not only takes into account how many billions or trillions of euros flowed from West to East, but also considers the social and cultural cost. And it is often those who were actively involved in German unification who have a problem with this approach.

The role of the economic crisis

The second reason why there have been new critical perspectives on the post-1990 is due to the global financial crisis of 2007/2008, which severely challenged, questioned, and undermined the prevailing paradigm in the West that dictates that there is no alternative to the current form of capitalist structures. This led to a revival of neo-Marxist approaches and to a questioning of what had actually occurred — or what went wrong — with the transformation of Eastern Europe and especially the GDR. This led to the realization that after 1990 neoliberalism had been particularly rampant in the East and had particularly serious consequences. By comparison, however, East Germany and Germany came off better than many other Eastern bloc countries.

The Kohl government was not as strong a believer in neoliberalism as, say, Margaret Thatcher in England, but some of the neoliberal patterns that were soon to gain ground in large parts of the Federal Republic were “tried out” in the East at an early stage. This included undermining collective bargaining unions and trade unions, which were weak in the East anyway, due to existing historical conditions. In the East, there was an attempt to weaken the unions from the outset, and the unions, in turn, fought pointless battles that had already been lost in the West in the 1970s and 1980s. Numerous issues converged in 2007/08 and the crisis shook the neoliberal world to the core, prompting a new perspective on the East.

Summer 2015

The third reason was the ill-named “refugee crisis” in 2015. It was not a “refugee crisis,” of course, but an identity crisis in Germany and Europe, which was not triggered by refugees, but by reactions in Europe and in Germany, making the term “refugee crisis” a misnomer. But the reaction of society, especially in East Germany, has of course prompted considerable reflection. There has been an eruption of widespread right-wing radical, neo-fascist, German nationalist (völkisch) attitudes and culture in the East, which are only partly reflected by the election results of the völkisch, even racist AfD party.

The potential dangers of these movements in the East and in Eastern Europe are far greater than these election results reveal, but people prefer to turn a blind eye. And there are widespread authoritarian patterns in East, which also raises the following questions: What actually happened in the East? Why has democracy, representative democracy, not taken root in the East? Why are the state institutions in the East so weak? Why do people have so many reservations about the media and the press?

East Germany is not unique

These tendencies have converged in recent years and have led to an increasingly critical debate about reunification. It has become clear to more and more people that what is going on in the East is not taking place in some free-floating space far removed from reality, but very specifically in Germany and very specifically in Europe.

What we are seeing in East Germany, Poland, and Hungary are by no means isolated processes; they reflect developments that are taking place throughout the world. In Denmark, the Netherlands, England, Brazil, the United States, Spain, Italy and France, no matter where you look in the Western world, you see this going on. It now seems to be dawning on people that an early radicalization has begun in East Germany and in Eastern Europe in response to the “catch-up modernization”, as Jürgen Habermas called it. A close look at the East now could perhaps help stop the East from “conquering” the West. It is not too late to Westernize the East, but this would only be productive if the West begins to be self-critical and puts its image as an imperial hegemon, racist, and rule-giver into the balance when considering the complex reality of the present-day, along with its ideals of freedom, the rule of law, and democracy. In order to strengthen the appeal of its ideals it must adopt radical measures to deal with its failings — it could try this out in the East, just as it tested other approaches following reunification in1990.