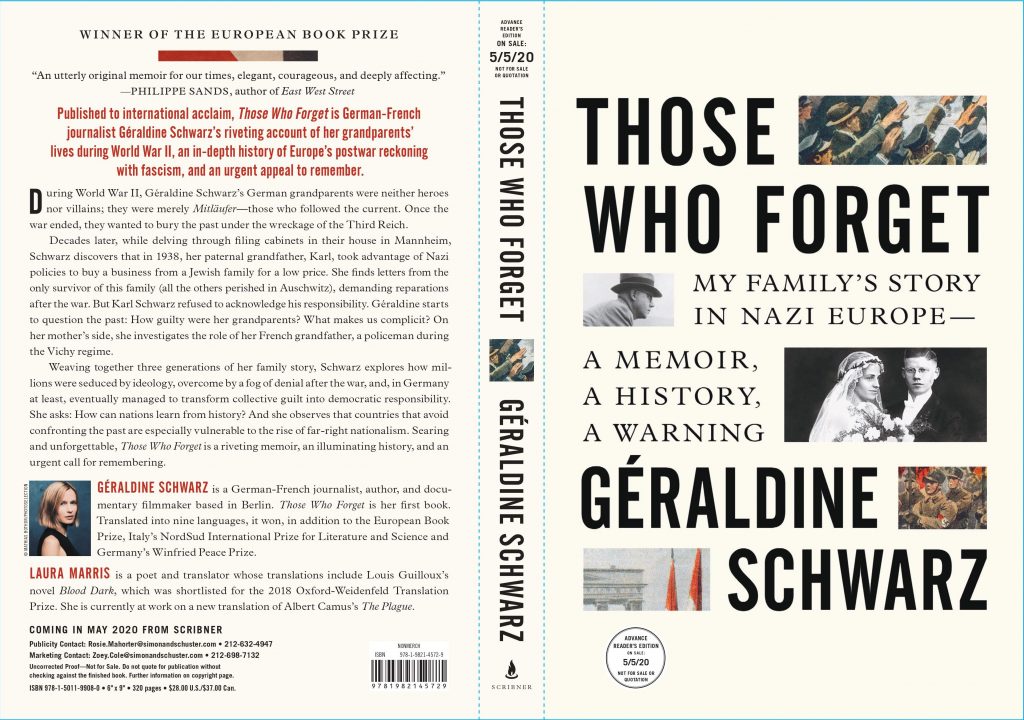

Picture: Astrid di Crollalanza

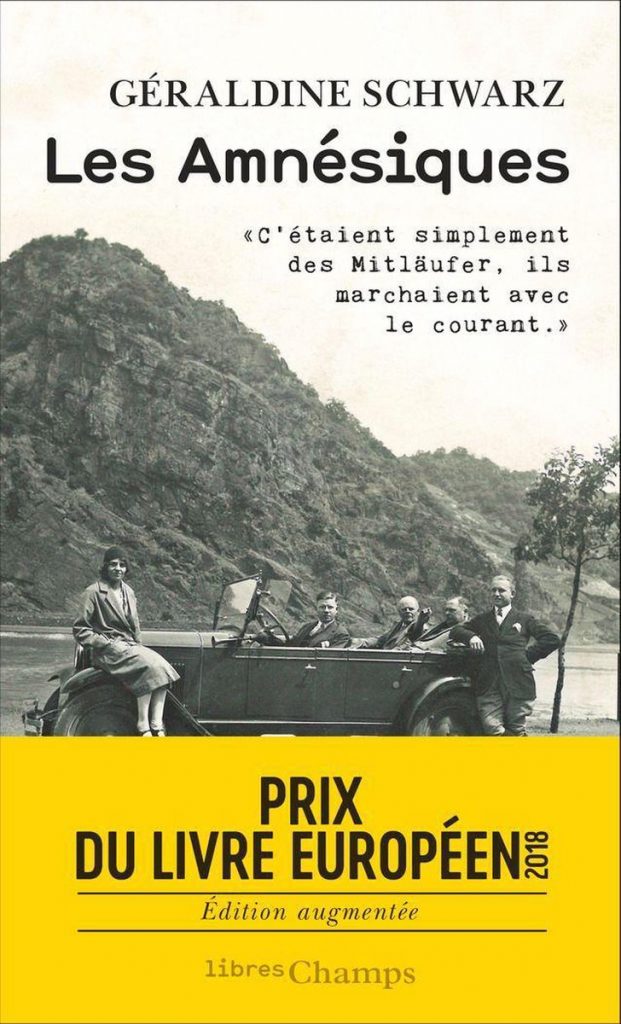

Géraldine Schwarz

French-German writer, journalist and filmmaker, author of the bestseller “Those Who Forget: My Family’s Story in Nazi Europe – A Memoir, a History, a Warning“

Up until World War II, remembering history served only to glorify the nation, stir up revanchism, or sanctify heroes. After 1945, the trauma of war, totalitarianism, and the Shoah gave birth to a new ambition in Europe: that of learning from history. Did it succeed?

The 75th anniversary of the end of the war coincides with an international health catastrophe that is putting us all to the test. Our reactions show that we have at least learned a fundamental lesson from the twentieth century: when we cease to be human, we destroy ourselves.

At a time when the technological and economic vision reduces man to algorithms, consumers, users, identical and substitutable models, the majority of Europeans have reaffirmed that each of us is unique and non-replaceable and has a fundamental right to life and physical integrity. Faced with utilitarian doctrines that accept the sacrifice of a minority in the name of the so-called general well-being, most of us have agreed that no one should be entitled to decide on the right to live or die, or to compare the value of one life with another – old or young, sick or in good health, French or German.

The solidarity shown by the younger generations with the older ones, the healthy with the sick, and (even though slightly late) of European countries with each other, have shown that in a situation of crisis we are able to let humanism guide our actions. The pandemic has reminded us that our ability to be human not only gives meaning to our lives but is the condition for all of us to survive.

But this teaching of the past remains fragile. Will it be able to resist the autocratic temptation that hangs over our societies, and the growing scourge of conspiracy theories? Will it be able to resist the amnesia that is eating away at us, the demagogues who are rewriting history, and the artificial intelligence that is replacing our memory?

Today, humanity is again threatened by worldviews that make humans a means and not an end – which reduce them to simple pawns at in the service of an ideology, a capitalist logic, or technological experiments. In societies which have never known freedom and which authoritarian rulers refuse to enlighten, many people consent, or resign themselves, to being mere instruments, provided they enjoy a minimum of material well-being and entertainment.

But even in Europe we are not spared the risk to lose sight of the fact that politics, economics and technology must always be at the service of man and not the other way around. Some admire the economic success of China or the world power of Vladimir Putin. Others dream of Franco or Mussolini. Crimes and oppression disappear behind the fascination with conquest, the law of the fittest, the virile orchestration of power.

Are we becoming amnesic? Have we forgotten the untold suffering? The fratricidal wars and the bombings? The tyrants who destroy the identity of humans, terrorize them, torture and manipulate them into disposable clones in the service of crime? Have we forgotten the promise of Europe: “never again”?

No, we haven’ forgotten “what happened”.

But we forget “how it was possible”.

If the Third Reich, Vichy-France, Mussolini, Franco and many others could commit crimes to such extend, it was/is? because the attitude of the majority of the society allowed them to. Their attitude was an accumulation of cowardice, opportunism, conformism, blindness and indifference, which, when combined, created the conditions necessary for the rise and consolidation of criminal regimes. In German, there is a word to design them: Mitläufer, those who follow the current.

We have not lost the memory of the crimes but the memory of our own moral fallibility. But precisely, we can not learn from the past if we don’t ask ourselves: how can ordinary citizens, or a society as a whole, become complicit in a criminal regime?

This reflection is essential because it sends each of us back to our present-day responsibilities – to our contradictions and the consequences of our actions and behaviour. It helps us realize that one doesn’t have to serve an unfair system directly to be complicit with it. Following the crowd through indifference, opportunism or conformism is also a form of complicity.

History may not repeat itself, but these sociopsychological and collective mechanisms that influence the behaviour of an individual and a society remain the same today as they were a hundred years ago. Populists, demagogues and autocrats have understood this well. No need for them to resort to oppression or force, which are prohibited in a democracy; the good old methods of manipulation are enough: spreading fear, designating scapegoats, causing division, sowing hatred and chaos. In this climate, all they have to do is take on the role of the saviour who has heard the needs of the people but has been ostracized by the corrupt establishment for having the courage to speak forbidden truths.

Although in the minority in most European countries, populists claim to be the sole representatives of the people – as if the people were a homogeneous bloc incapable of nuances and differences. They promise to return to the people control over their destiny, in what would be “real” democracy. In fact their paternalism infantilizes the population and paves the way for dangerous antidemocratic abuses. Politicians who declare “I am the people” are claiming to be the direct emanation of the popular will; History has shown where this can lead: to consider that there is no need any more to consult the people.

The myth of the providential martyr still exerts an important power of attraction today as it did in the past. Isn’t it tempting to take refuge in the role of the victim and entrust our salvation to a saviour rather than assume our responsibilities as citizens in a democracy?

Another psychological weapon of the Third Reich that populists and autocrats use today is distorting the meaning of words. Tricking us into lowering our guard, they pretend to stand for values that most of us hold dear. Some even go so far as to include the terms of freedom or democracy in their names… the Freedom Party of Austria, the Dutch Forum for Democracy, the Czech Freedom and Direct Democracy.

We have to look behind the slogans to understand. The freedom becomes that of comparing strangers to parasites; democracy becomes the dictatorship of one opinion, that of the “true patriots”; defending Europe amounts to “re-establishing old paternalistic values” from a time when people “didn’t venerate human rights”.

Hatred is disguised as “freedom of speech”, anti-Semitism as “freedom of opinion”, authoritarianism as “illiberal democracy”. The unacceptable is masked to become acceptable. How many see in populist rhetoric the chance to pass off their frustrations as courage, their resentment as resistance against “political correctness”? How many adopt the same provocative and simplistic discourse to hide their ignorance in the face of the complexity of the world?

It is so reassuring to be part of a self-proclaimed chosen people, a white, Christian and heterosexual club with strict rights of admission – so tempting to wield control without possessing any other merit than that of one’s origins or skin colour. The Third Reich was a master in this: it flattered the narcissism of non-Jewish Germans by calling them the master race and at the same time worked to undermine their moral values. Evil became good and good became evil. “Empathy is a weakness” was a motto of the SS.

This reversal of the moral compass is all the easier when minds are confused, as at present. We are going through a period of multiple crises – pandemic, climatic, political, technological, economic – where it is difficult not to lose our perspective. Demagogues of all stripes are exploiting this fertile terrain to spread false information, to discredit the facts, to denigrate scientific reasoning and argumentation, to impose the irrational and the emotional, and to disseminate aberrant conspiracy theories. The purpose is to undermine our values and our knowledge. The lie was already at the heart of the totalitarian system. The aim of that strategy, wrote political scientist Hannah Arendt, is not for a society to believe these lies but to lose the ability to distinguish right from wrong and to judge or act. And a society which doesn’t share anymore truths and values disintegrates and can be easily manipulated.

The German philosopher Theodor W. Adorno analysed how the confusion between belief and knowledge can lead to a delusional representation of the world and translate into acts of madness. In Dialektik der Aufklärung (1944) he describes the various stages. We begin by refusing to confront our opinion – by definition subjective, and so with limited validity – with others, to verify their origin and justification. Opinion then becomes conviction, that is/means, a simple explanation of the world that requires no reflection. We then take refuge in the stubborn rejection of any argument, any reality, any evidence that might contradict this conviction, which is often nothing more than a mixture of rumours, conspiracy theories, emotions, and amalgamations. Then, Adorno goes on, from conviction one passes into paranoia: our opinion becomes an integral part of our personality, and any contradiction is felt as a personal attack. One ends up projecting one’s inner feelings onto the outside world and taking one’s opinion as truth. Paranoia can lead to acts of madness, as delusional anti-Semitism led to the Holocaust.

Adorno’s analysis is very topical at a time when beliefs and conspiracy theories threaten to replace the words of experts. How did we come to this? Triumphant individualism has exacerbated the idea that everyone is entitled to defend, without limits, their particular rights, desires, opinions, beliefs. If at first sight this may seem to serve democracy, in reality it threatens it because no collective project can emerge from the juxtaposition of a multitude of diverse demands, often divergent, even antagonistic, alongside the rejection of the principle of representation. This danger is amplified by social networks, which, far from encouraging Internet users to exchange their ideas and points of view and to build nuanced theories, actually radicalizes them and locks them in their own certainties, due to the logic of personalization algorithms. Little by little, users can end up regarding their opinions as universal truths.

However, there is no inevitability about this. The demagogues use the means of today, but the methods of yesterday, and so we can identify them. The socio-psychological mechanisms that make us so vulnerable have not changed since the French sociologist Gustave le Bon published “The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind” in 1895, a reference work for Benito Mussolini and Hitler’s Propaganda minister Josef Goebbels. Therefore memory can be a powerful weapon against manipulators and can help us to know ourselves better and sharpen our awareness of our malleability.

But to reach that, countries must have the courage to face the shadows of the past and transmit the memory of their own fallibility to their citizens. Unfortunately, few in Europe have had this courage. Germany has been a pioneer in placing the role of Mitläufer at the heart of its task of coming to terms with the past. After twenty years of amnesia, in the 1960s a younger generation forced society to face its responsibilities for the crimes of the Third Reich. This reflection made it possible to transform collective guilt into democratic responsibility. It allowed something positive to grow from a negative legacy: the building of one of the world’s soundest democracies.

This model could inspire certain societies which persevere in denying their past responsibilities as Mitläufer in criminal systems – Fascism, Stalinism, or colonialism –They have trouble understanding that to transform the weight of the past into wealth, one must not ignore its shadows but rather confront them. A repressed history always returns at a gallop, in the form of community and international tensions, racism, and populism.

Facing up to the shadows of history shouldn’t be done in a culture of guilt. Nor should it be instrumentalised to stir up hatred or sectarianism. It is not a moral accessory to look good. Keeping memory alive can do much more than this if we learn to approach it intelligently. It can guide us to understand the world instead of suffering it, to avoid mistakes, to identify dangers – those that come from others but above all those that come from ourselves. The message is empowering: humans are not as helpless as they may think, and they often have the choice to use their power.

Memory can serve not only democracy but Europe as well. With a transnational approach, we can learn to change perspective, placing ourselves in the shoes of yesterday’s enemy, accepting the view of another country or community on our own history, posing questions and engaging in dialogue. Bringing together European histories at local, national and also family levels can help us to shape a European memory that can guide us in these times of disorientation and give us the perspective and the experience necessary to face the challenges that await us.