Ventotene 80

80th anniversary of the Draft Manifesto for a Free and United Europe 1941-2021

* View of the Santo Stefano island seen from Ventotene (1941) |

The construction of democracy in countries and societies has gone hand in hand with the fight against civil wars and humanitarian or political crises of all kinds. The construction of Europe also stems from post-conflict eras and the atrocities endured in the wake of the Second World War. Europe seems to be constantly tackling various crises that make it stronger but put it to the test time and time again. We are often oblivious to the price paid to achieve certain peace and stability after so much conflict, violence and disaster. From the perspective, once again, of a global pandemic crisis, I believe I can assure that European democracies will come out stronger, without forgetting the new challenges and tangential weaknesses they are up against.

In an endeavour to restore the values of European construction based on history and memory, we have worked alongside various institutions and professionals to produce this volume. A volume that, similar to our previous work on the figure of Robert Schumann, seeks to give us a deeper insight into the democratic and foundational values of the European Union, into that new post-war Europe and its main players. The European Observatory on Memories, which enjoys the support of the European Commission’s former Europe for Citizens programme, together with the European Parliament’s Jean Monnet House and the Istituto Altiero Spinelli, wish to recover the figure of Altiero Spinelli as one of the founding fathers of the current Union. They have joined forces to develop a compendium of historical biographies, political processes and the history and memorialisation of public and symbolic places as important as the Santo Stefano prison in Ventotene. We hope this approach heeds cross-cutting perspectives, related to gender and memory. Examples include the text on Ursula Hirschmann, who at times played a more discreet role in the process of reflection, debate and authorship of what became an intellectual and political movement of a new and strong democracy in a new and reconstructed federal Europe. As you know, all this is underpinned by the so-called Ventotene Manifesto.

We, the authors, specialists and experts, who engaged in the debates held in previous seminars in May 2021, have created synergies that extend beyond this joint volume. The aim of our European Observatory on Memories has always been to go one step further and to consolidate the international relations that we establish on the basis of critical reflection and the creation of stable and permanent frameworks. Commemorating Europe and its processes and founders is more necessary than ever. That said, I wish to be optimistic when I assert that it coincides with the establishment of new European programmes that also advocate and foster the past’s values in the present, the values of memory and democracy in the rights and freedoms of today’s Europe. For example, the European Commission’s new Citizenship, Equality, Rights and Values programme. It marks an achievement and a bold resolution that encourages us to place our trust in today’s Europe. And to deposit greater trust in its political and democratic origins, where culture, education, citizenship and public policies must take their rightful place.

Our thanks once again for the collaboration of the Jean Monnet House, the Istituto Altiero Spinelli and the colleagues who have contributed to this must-read book.

JORDI GUIXÉ

Director of the European Observatory on Memories (EUROM)

Group of politicians confined to the island of Ventotene. 1930-1940 | Wikimedia Commons

When it comes to European unity, 2021 is a year of double celebration. Seventy years ago, the signing of the Treaty of Paris paved the way for the first European Community, devoted to the sharing of Coal and Steel Production. It was the very first practical step towards the integration of our continent. Eighty years ago, on the tiny Italian of Ventotene, in the heat of WWII, a group of prison inmates wrote a compelling blueprint for a future without war, with the title For a Free and United Europe. A Draft Manifesto.

At the Jean Monnet House in Houjarray (France), we have had the opportunity to commemorate the Treaty of Paris, and we are now happy to join forces with the European Observatory on Memories and the Istituto di Studi Federalisti Altiero Spinelli to mark the 80th anniversary of the Manifesto of Ventotene.

In our age of uncertainty, does such remembrance matter? The two events were very different in nature. The former signalled an unprecedented institutional move on the international arena: for the first time in history, governments were relinquishing part of their sovereignty to merge some of their key policy areas, in hopes of preserving peace. The latter was an act of thinking among comrades—all of them in principle with their ability to act curtailed—pointing at a federal Europe as the only way for a better world, a world in peace. Yet both events have something important in common: they both stemmed from the strength of individual will against all odds. The Treaty of Paris was a multilateral answer to an acute deterioration of security, true; but it was Jean Monnet’s own restlessness at the prospect of a new war which prompted many successive days of drafting, without exactly knowing how and by whom it would be received, what would be known as the Schuman declaration, prefiguring the Treaty. The Manifesto of Ventotene was the work of Altiero Spinelli, Ernesto Rossi, and other farsighted individuals: they were persuaded that if nation-states were to be reconstituted after the war according to pre-war premises, with national sovereignty intact, it would inevitably lead to war again. If it is fair to acknowledge the men of the practical steps towards European unity in the fifties—Spaak, Adenauer, de Gasperi, Schuman, all of the often-touted “founding fathers”—it is equally fair to acknowledge the individuals who, out of nothing, when everything seemed lost to war, laid out a clear vision and fought for it. Today it is worth recalling that, in the face of adversity, their answer was the opposite of despair.

Beyond its powerful political message, the story of the Ventotene Manifesto strikes us for its epic overtones, and it is one that defies certain received ideas about the origins of European unity.

First, the theatre of the saga of European unity is not solely confined to Western Europe. The group of Ventotene included some Albanians, in the same way that, before the Cold War’s Iron Curtain fell, pro-European activists were to be found in all four corners of our continent.

Second, those determined activists included both men AND women: some of those women deserve to be called founding mothers. Ursula Hirschman transported the text written on cigarette paper to the mainland, investing herself to the fullest in the dissemination of the Manifesto and the advancement of Federalist ideas. In the same lineage of founding mothers, we find Louise Weiss (also active in the interwar period) and Simone Veil, the first president of the directly elected EP, among many others, alas not always acknowledged.

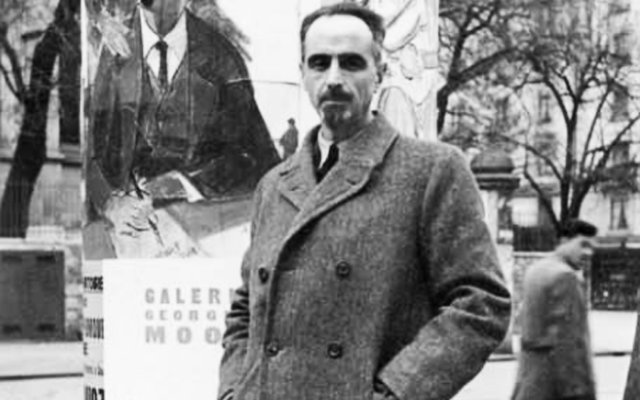

Third, the frontrunners of European unity came from all ideological strands. Spinelli was a young journalist arrested for his Communist ideas, imprisoned for long years, then kept in confinement. He was expelled from the Italian Communist party for his rejection of Stalin’s policies, and he maintained his convictions in other organisations.

The men and women who authored and rapidly disseminated the Ventotene manifesto might not have suspected it, but they were marking the beginning of an astonishing decade for European unity. The war ended in 1945, and the next year Winston Churchill advocated for the creation of a United States of Europe, while pro-European activism grew amid post-war reconstruction. In 1948, more than 700 individuals from across the continent—Spinelli with a prominent role among them—gathered in The Hague in the Congress of Europe to realize ideals with action. One of the results was the creation of the Council of Europe in 1949, but it was clear that its cooperative rationale was a world apart from a federal Europe. Conversely, both the Schuman Declaration and the international treaty it informed, the Treaty of Paris, laid down concrete foundations for what was seen as a first step to a European federation. To be sure, Spinelli judged some of those petits pas, and the petits pas method itself, insufficient. But that did not prevent him from being involved in key actions to move forward from stalemates. Thus, the decade’s story is the transit from idealism to pragmatism. Spinelli, an idealist, did not abjure pragmatic moves, as Monnet, a pragmatist, did not despise but worked to streamline idealism. Jean Monnet wrote: « Rien n’est possible sans les hommes, rien n’est durable sans les institutions »: such seems to be the meeting point between the two men’s otherwise very different methods.

The Manifesto started its dissemination in federalist circles even before its authors and contributors left the island. One of them, Eugenio Colorni, was unfortunately killed shortly before the end of the war. Ursula Hirschman, Eugenio’s widow, married Altiero, and the couple renewed and intensified their activism. Spinelli devoted himself to the propulsion of the federalist movement, and joined the Action Party, named after Mazzini’s party. Mazzinian thought, for Spinelli, is not just a distant echo, but something deeply linked through a chain of influences stretching to the 19th century (Ernesto Rossi, Eugenio Colorni, Gaetano Salvemini, Carlo Roselli). Even if modern lingo opposes nations/nationalism to internationalism, self-rule and international brotherhood are notions perfectly reconciled in Mazzini’s texts.

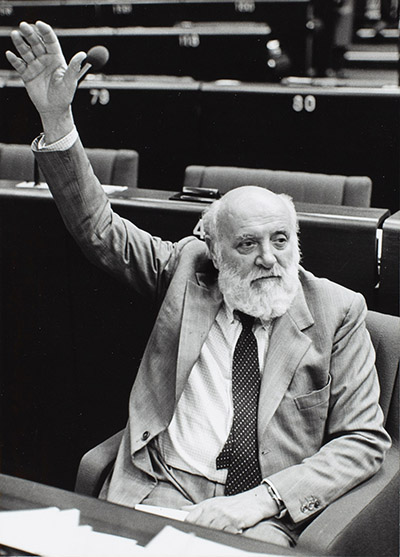

In the next decades, Spinelli was sometimes disappointed with the sluggishness of the unfolding of European unity, but his advice was essential even when a “moderate” approach prevailed. Ultimately, he entered the fray of institutional politics. In 1970, he became European Commissioner. In 1976, member of the Italian Camera dei Deputati. In 1979, Member of the European Parliament. At the European Parliament, he led an institutional revolution, at the helm of the Crocodile Club, for the creation of a European federation. In this context, a new committee for institutional reform chaired by Spinelli produced a “Draft Treaty establishing a European Union”. Although the member states did not approve the text, it paved the way for the European Single Act and the Maastricht Treaty, which effectively established a European Union, albeit not a federal one.

Spinelli died in 1986, but his federalist ideals live on. For many, Europe’s ever-growing unity is the best answer to the challenges of our time.

Martí Grau i Segú

Head of service and curator, Jean Monnet House, European Parliament

‘A Draft Manifesto’. Ventotene and the Struggle for European Unification

share

by Giorgio Anselmi 1, Michele Fiorillo 2 and Mario Leone 3

“The island is less than two kilometres long, between two and eight hundred metres wide, only slightly undulating, so that the winds sweep it freely, and is almost devoid of trees. Normally one could see nothing but sea and sky all around, (…) some of the windows of Gaeta’s houses sparkled, reflecting the setting sun’s rays back at us, as if to remind us that the continent on which, from Gaeta to Canton, a terrible game was deciding the fate of mankind, was not so far away after all”.

A. Spinelli, How I Tried to Become Wise (1984)

Ventotene, 1940. The pavilions of the former penitentiary

Source: Altiero Spinelli Institute for Federalist Studies

Altiero Spinelli and the Confinement of Ventotene

Ventotene. A political confinement under the Fascist regime since 1930, after the institution of police confinement through the law on public security and the law on measures for the defence of the State, the island was only connected to the mainland by a post office. The internees were subjected to a thorough check-up and were given the “Carta di permanenza”, the red booklet with the instructions they had to follow – including finding a job, since the money they were given was not very substantial. There was a limited walking space, an impenetrable confinement limit (with signs and barbed wire), control by public security agents who also carried out surveillance operations on the most ‘irreducible’. Appeals had to be answered in the main square, now Piazza Castello, with compulsory times for leaving and returning to the ‘cameroni’ (specially built, given the increase in the number of guests – up to 800 in the most crowded periods), a ban on talking about politics, and the possibility of writing (subject to authorisation from the management) one letter (or postcard) a week. The organisation of the canteens was left up to the internees, according to the political movement they belonged to: among these were seven communist canteens, two of the anarchists, two of the ‘Manchurians’ (i.e. those internees who were isolated from the others because they were considered informers), one of the ‘giellisti’ (i.e. “Giustizia e Libertà” militants), one of the Socialists (Sandro Pertini was the head of the canteen) and the ‘A’ canteen for the sick, particularly tuberculosis patients. Later on, Altiero Spinelli would set up a new canteen, the ‘E’ canteen of the group of European federalists, of which he became the animator and ‘pater familias‘.

Il Vassoio di Ventotene (The Ventotene Tray) is a work of art created by Ernesto Rossi in 1940 during his confinement on the island of Ventotene. Housed in the Historical Institute of the Resistance in Tuscany in Florence, it represents one of the most vivid iconographic testimonies of the world of those imprisoned during the Second World War | © No known copyright restrictions

“Those years on that island – he wrote in his autobiography How I Tried to Become Wise,- are still present in me today with the fullness that only the moments and places in which that mysterious thing that Christians call election takes place have. The disiecta limbs of feelings, thoughts, hopes and despair were then recomposed in a new design, surprising for myself; my weakness became strength; I felt that a new extraordinary consonance was being formed between what was happening in the world and what was happening in me; I understood that until that moment I had been similar to a fetus in formation, waiting to be born, that in those years in that place I was born a second time”.

Spinelli was sent into exile, first to Ponza in 1937 after serving 10 years in prison, and finally to Ventotene in 1939 where he met Ernesto Rossi and Eugenio Colorni, who were his main interlocutors in the fertile debate that resulted in the Manifesto, with the participation of Ursula Hirschmann, the ‘giellisti’ Dino Roberto and Enrico Giussani, the Republicans and veterans of the war in Spain Giorgio Braccialarghe and Arturo Buleghin, and the young Slovenian from Ljubljana Milos Lokar.

On this island, a training ground for life, segregation and ‘redemption’, it was this group of ‘visionaries’ who ended up drafting and putting together a text that identified the historical need to unite and liberate Europe from dictatorships by means of reason and collective action, in a supranational framework capable of overcoming nationalist aporias towards perpetual peace: the project of a manifesto that was to mobilise the struggle for the freeing and unification of Europe.

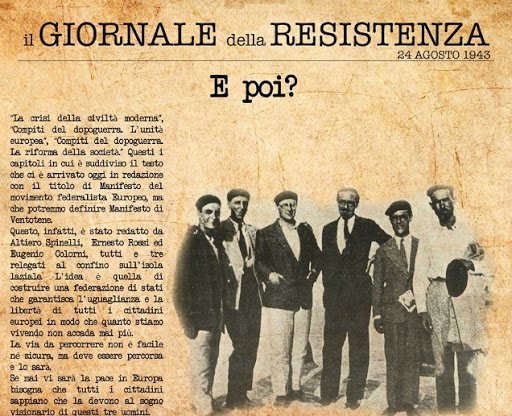

The resistance diary, 1943 | © European Federalist Movement 2021

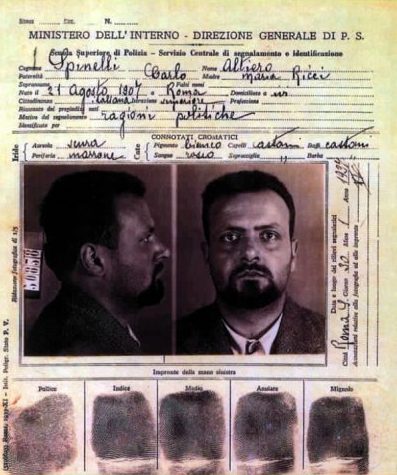

Information sheet on Altiero Spinelli (1937) | © European Federalist Movement 2021

The Crisis of Civilisation and the Manifesto Project

Whoever reads the Ventotene Manifesto today – whose precise title is Per un’Europa libera e unita. Progetto d’un manifesto [“For a Free and United Europe. A Draft Manifesto”] – is struck first and foremost by its style, especially if not guided by political convictions. It is hard not to think of the most famous of political manifestos, that of Marx and Engels published in 1848. In the text, written for the most part by Spinelli, who came from the communist tradition, from which he had become autonomous, we find the same assertiveness, sculpted in dry sentences, peremptory statements, and cutting judgements.

There is also, especially in the first part (The Crisis of Civilisation), the skilful use of dialectical antithesis, which refers back to Marx’s judgement on the bourgeoisie unable to dominate the forces it has aroused and which will eventually sink it, similar to “the sorcerer who can no longer dominate the subterranean powers he evokes”. Here it is the national state that “from being a powerful leaven of progress” has turned into a “divine entity”, a totalitarian machine, a “master who has relegated all his subjects into servitude”. The liberal system itself, which became fully democratic with universal suffrage, has been emptied from within by the privileged classes to run the state machine to their own, exclusive advantage, under the guise of pursuing higher national interests”. Finally, even the sciences and the critical approach, “to which the greatest achievements of our society are due”, have been enslaved by the new totalitarian demons: physiology to prove the existence of a chosen race, economics to justify autarchy, history falsified “in the interests of the ruling class”.

In a new dialectical reversal, however, the totalitarian monster is described as destined for certain defeat: “Vast numbers of men and immense wealth are already lined up against the totalitarian powers whose strength has reached its apex and can now only gradually wane. The opposing forces, on the other hand, have already overcome the hardest challenges and they are growing in strength.” Not without noting that in the summer of 1941 – while the authors were giving final shape to the Manifesto and Hitler was still victorious on the continent – either exceptional clairvoyance or extraordinary faith was needed to take this outcome for granted, it is the palingenetic character attributed to the war in progress that brings out the political proposal of the second part: European unity as a post-war task.

It is precisely in this part that the epochal and historical value of the Ventotene Manifesto is revealed, as Norberto Bobbio has acutely noted: “Federalism must henceforth be thought and action. The detachment from previous attempts is very clear. (…) After all, everything that has been written before in very different historical conditions belongs not to history, but to prehistory: it is an antecedent that can easily be taken for granted.”

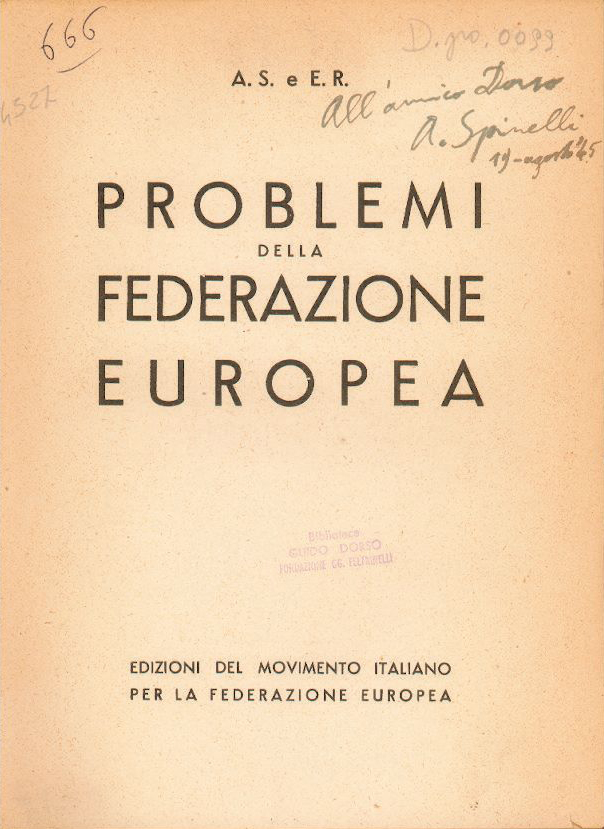

Cover of the book Problemi della federazione europea (Problems of the European Federation), published in Rome in January 1944. The edition includes a new version of the Manifesto, a preface by Eugenio Colorni, and two new essays by Spinelli, “Gli Stati Uniti d’Europa e le varie tendenze politiche” (The United States of Europe and Various Political Trends) and “Politica marxista e politica federalista” (Marxist Politics and Federalist Politics). It features the initials of the two authors of the Manifesto | Source: Altiero Spinelli Institute for Federalist Studies

Federalism, Reform of Society and the Movement for a Free and United Europe

The federalist theory was discovered by Spinelli in his discussions with Rossi about the crisis of the League of Nations, the weakness of which had already been criticised in a series of articles published in 1919 in the Corriere della Sera signed by a mysterious Junius – the pseudonym of the economist and future President of the Italian Republic Luigi Einaudi – then collected in a volume published by Laterza which attracted the attention of the two internees. Prompted by Rossi as a fellow economics professor, Einaudi sent them some books on English federalist theory from the 1930s. Among these books, Spinelli mentions in his autobiography The Economic Causes of War by Lionel Charles Robbins (1939): in it we find a chapter entitled The United States of Europe, dedicated to the prospect of peace to be achieved by overcoming the conflict between the different European states through the example of the American Federation.

First issue of L’Unità Europea (European Unity, 1943)

| © European Federalist Movement 2021

The Manifesto declares the necessary “definitive abolition of the division of Europe into national, sovereign states”, to be achieved through a federal reorganisation of the continent, since a balance of independent European states was no longer conceivable after the failure of the League of Nations which “claimed to guarantee international law without the need of a military force to impose its decisions”.

If therefore the prospect of a European federation was not original in itself, revolutionary is the theoretical-practical caesura that indicates an unprecedented political watershed: the new “dividing line between progressive and reactionary parties” will be that which separates on the one hand those who “conceive as the essential aim of the struggle the old one, that is the conquest of national political power – and who will, albeit involuntarily, play into the hands of the reactionary forces by letting the incandescent lava of popular passions solidify in the old mould, and resurrect the old absurdities”, on the other hand those who “will see as a central task the creation of a solid international state, will direct the popular forces towards this end and, even having conquered national power, will use it in the first line as an instrument for achieving international unity.”

No longer a distant horizon, therefore, but an urgent call to take sides politically and a concrete project to build the future here and now, as Eugenio Colorni reiterated in his Preface to the Manifesto in January 1944: “The ideal of a European federation, prelude to a world federation, while it might have seemed a distant utopia even a few years ago, presents itself today, at the end of this war, as an achievable goal and almost within reach”.

In fact, a revolutionary crisis is here imagined to be imminent, and therefore a “European revolution” as possible, which “must be socialist”, according to a line of general reform of society described in some detail in the third and last part of the Manifesto (written mainly by Rossi, except for the concluding pages where Spinelli’s pen returns): private property abolished, limited or extended on a case-by-case basis within the framework of the formation of a European economic life; private monopolies combated also through large-scale nationalisations in strategic sectors of collective interest; land reform to make farmers widely owners; industrial reform to extend worker ownership through cooperative management or worker ownership; provisions for young people to “minimise the distances between the starting positions in the struggle for life”; roughly equal average wages for all occupational groups; and even the prefiguration of a kind of universal basic income: “a series of provisions which unconditionally guarantee to all, whether they can work or not, a decent standard of living, without reducing the incentive to work and save” so that “no one will be forced by misery to accept jugular work contracts any longer”.

However, the European revolution was not going to fall from the sky: it was necessary from the outset to “lay the foundations of a movement capable of mobilising all the forces to give birth to the new body that will be the most grandiose and most innovative creation to have arisen in Europe for centuries, to constitute a solid federal state”: the Movement for a Free and United Europe, to be built “by propaganda and by action” and by establishing “agreements and links between the individual movements that are certainly being formed in the various countries” – and the Manifesto would in fact be taken to the continent, in particular thanks to Ursula Hirschmann and Ada Rossi, and circulated by means of cyclostyled or typewritten versions among clandestine anti-fascist groups, even outside Italy, particularly in Switzerland among exiles from all over Europe, coming to inspire the Declaration of the European Resistance movements of July 1944.

In the conclusion of the Manifesto this organisational vision is specified in a call to build a revolutionary party that would not follow the fickle movements of the masses, but would guide – even through a dictatorship – the construction of the new state, “and around it the new true democracy”. Here is a remnant of Spinelli’s Leninist training, which he himself will indicate in his memoirs as one of the errors of the Manifesto, as well as the optimism that made him imagine European unity as something that would be imminently realised, having failed to foresee that the continent’s destiny would instead be determined largely by the external pressures of the United States and the Soviet Union.

Formed as the Movimento Federalista Europeo [European Federalist Movement] in Milan in 1943 on Spinelli’s initiative, the European federalists would continue to speak of revolution even after Spinelli, even though the ‘revolutionary situation’ predicted by the Manifesto did not come about and European unification has so far been achieved through a gradualist process that has not yet been concluded – largely inspired by Jean Monnet’s ‘functionalist’ approach, which has, however, suffered serious setbacks on several occasions, particularly in recent decades.

On the other hand, the Draft Manifesto of 1941 will somehow find its evolution and deepening in the more mature Manifesto of the European Federalists written entirely by Altiero Spinelli and published in 1957. After the failure of the European Community of Defence in 1954 – a project that had seen a phase of collaboration of the federalists with some governments and in particular of Spinelli with De Gasperi and Monnet – here the democratic method of the Constituent Assembly is formalised, a prospect that still seems to be of urgent relevance in the political struggle for the birth of a European Republic:

“The European Constituent Assembly, rising from a massive popular vote, and therefore feeling itself to be the legitimate representative of the European people and its aspirations, will have a strong and proud awareness of its mission, will not be willing to give in to national flattery and pressure, and, whatever its composition, will be able to find the necessary agreements and compromises to achieve the approval of the federal Constitution.”

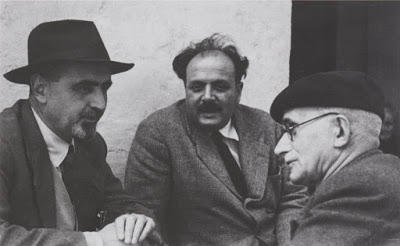

The Italian delegation to the first UEF (Union of European Federalists) Congress, including Gustavo Malan, Guglielmo Usellini, Ernesto Rossi, Altiero Spinelli and Alberto Cabella. Montreux, Switzerland, 1947 | © Union of European Federalists

First federalist event, Rome (1947) / European Federalist Movement. “Agostino Trabalza” Session in Rome (1947) | © European University Institute. Reference Code: ER.A-3

80 years on, for another Europe.

The Ventotene Manifesto

share

by Pier Virgilio Dastoli 4

When I refer to the Ventotene Manifesto in university and school meetings, I am struck by the fact that many young people believe that Altiero Spinelli and Ernesto Rossi’s ideas are as topical as ever; in particular the idea that the proposal to create a European democratic power, as a way to find a permanent solution to common problems of Europeans at the end of the war, is even more valid today as a way of addressing other new problems we have in common.

Far more than among the political leaders who, in the face of the serious crisis that has struck the European Union, are helplessly floundering from summit to summit, looking for a way out, without a vision of the whole, or rather without any vision at all, I have discovered in many young people an idea that can be expressed in the same terms in which it was put by Spinelli in 1957:

The project for a European federation was not a fine ideal to pay tribute to and then move on to something else; it was an objective for which we had to act immediately, people of our generation. This was not an invitation to dream, but an invitation to work.

I also discovered that they share another of Spinelli’s essential ideas on the nature of «his» Federation:

It is not presented as an ideology, it does not aim to depict an existing power in one way or another […] it is a sober proposal to create a democratic European power, at the heart of which ideologies may well develop, if people find them to be necessary, but it is very different from them […] the recognition of diversity and of the brotherhood of the national experiences of European peoples, in the midst of whose languages, writers and thinkers we have been living for years without ever feeling closer to them if they are Italians, or more distant if they are foreigners.

The Manifesto was the meeting point between Spinelli and Rossi’s complementary ideas. Spinelli expressed his interest in the freedom of the individual and of society but he also implied that this struggle could not stop at the borders where socialism was being built. Rossi criticized capitalism, trade unionism, communism and its project of «eradicating poverty» by grafting a piece of communist economic constitution into a market economy. The conversion to democracy had led Spinelli to realize that political action should aim at using power in the service of freedom, whereas the nation state was the enemy of freedom.

The fight for the freedom of the individual and of society had led Spinelli to break up with the Italian Communist Party as early as 1935 in Civitavecchia, after the start of the season of Stalinist terror. This breakup was formalized in 1937 in Ponza when he was expelled from the party for «ideological deviation and petit-bourgeois presumption». As for Rossi, his criticism of capitalism and communism – together with a brief reading of texts on English federalism – had persuaded him that only a European federation would ensure greater resources for development, subtracting them from the preparation of wars decided on by the growing power of the military elite and from administrative centralization.

In the Ventotene discussions that preceded the drafting of the Manifesto, the belief emerged that a European federation would be the only reasonable solution to the problem which had plagued Europe since 1870, i.e. the peaceful coexistence of Germany with the other peoples of the old continent.

A federation would be, above all, a way for democracies to control «those crazy Leviathans» (in Spinelli’s words), namely the nation states of Europe, since a federal state would prevent them from becoming a means of oppression and they would prevent the federal state from becoming one itself.

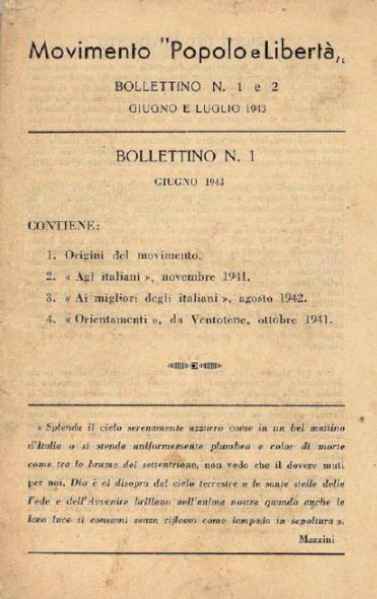

First and oldest cover version of the text published in the Manifesto in the Bulletin of the “Popolo e Libertà” (People and Liberty) Movement (no. 1, June 1943, pp. 8-26, entitled Guidelines and featuring the caption at the bottom “From Ventotene, October 1941”) with no division into chapters, just into paragraphs (from 1 to 20) | Source: Altiero Spinelli Institute for Federalist Studies

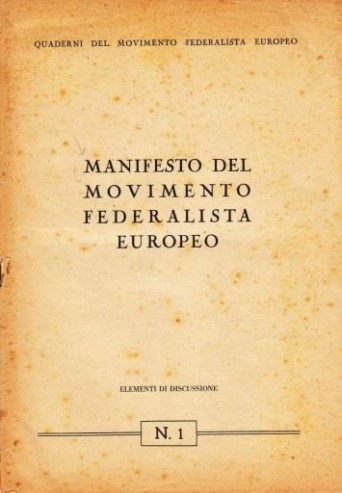

Cover of the second printed edition of the Ventotene Manifesto contained in No. 1 of the “Quaderni del Movimento Federalista Europeo” (Notebooks of the European Federalist Movement), entitled “Manifesto del Movimento Federalista Europeo” (Manifesto of the European Federalist Movement), with an introduction dated 29 August 1943. It is here that the text acquires its first subdivision into four chapters (which later became three in the last version of the Manifesto): I) The Crisis of Modern Civilisation; II) Post-War Duties – European Unity; III) Post-War Duties – The Reform of Society; IV) The Revolutionary Situation: Old and New Trends

| Source: Altiero Spinelli Institute for Federalist Studies

Unlike a part of the federalist theory which considered the nation as evil in itself, the authors of the Manifesto believed that the ideology of national independence was «a powerful leverage for progress» but that it brought with it «the germs of capitalist imperialism».

Spinelli was fully aware of the fact that the federalist culture was alien to the political cultures existing in the countries of Europe, which, he believed, would emerge from the war to try and restore national democracies, despite the universalist origin of Catholic movements, the internationalist origin of socialist and communist parties and the cosmopolitan origin of forces of liberal inspiration. He knew that these parties were now accustomed to addressing every problem on the tacit assumption that the national state did exist. They considered international problems as foreign policy issues which could only be resolved through diplomatic actions and agreements between the various governments.

Yet he was convinced that the ideal of a European federation –«a prelude to a world federation» – would emerge at the end of the war as an attainable goal, «almost at hand», and that «forces from all social classes» would express their interest in it. Spinelli was opposed to using diplomatic channels, preferring what is called in the Manifesto the revolutionary ‘people’s movement’: once certain events have occurred, it would be virtually impossible to go back to the previous situation.

Although they were confined on the island of Ventotene, Spinelli, Rossi and Colorni succeeded in analyzing with the utmost clarity the state of the war in 1941. They predicted the defeat of German imperialism and totalitarian powers; on the other hand, they did not predict that Europeans would not remain their own masters in the search for their future. But Europe had ceased to be at the center of the world, and they would be heavily conditioned by powers outside Europe: Soviet imperialism in the East and the hegemony of the USA in the West.

Thus the road taken by the new democracies born after the war was not aimed at the elimination of national sovereignty but at reinstating the national States, albeit within the limits and framework of the process of community integration, which began with the “small Europe” of Six countries, following the functionalist model conceived by Jean Monnet in which the objective of creating a federal State was replaced with a new goal of supranationality.

Spinelli’s criticism of the functionalist model – radically expressed at the time of the birth of the European Communities with the Treaties of Rome (‘the mockery of the Common Market’, wrote Spinelli in 1957) – never came to an end, not even when he acknowledged the federalist opportunities offered by the community construction.

The functionalist approach –which Jacques Delors, president of the European Commission from 1985 to 1995, subsequently defined as ‘the step-by-step method’ –was continually challenged by Spinelli. He did not accept the idea that a lasting and effective union could be created gradually while keeping the various sectors of the life of the state’s separate from each other, leaving until the end the creation of a democratic and federal power.

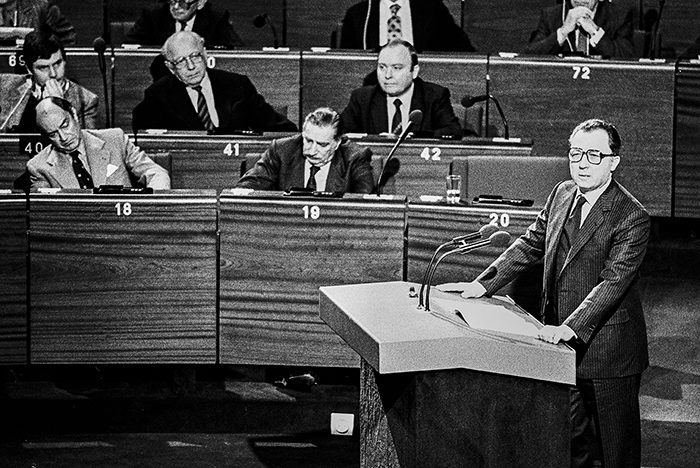

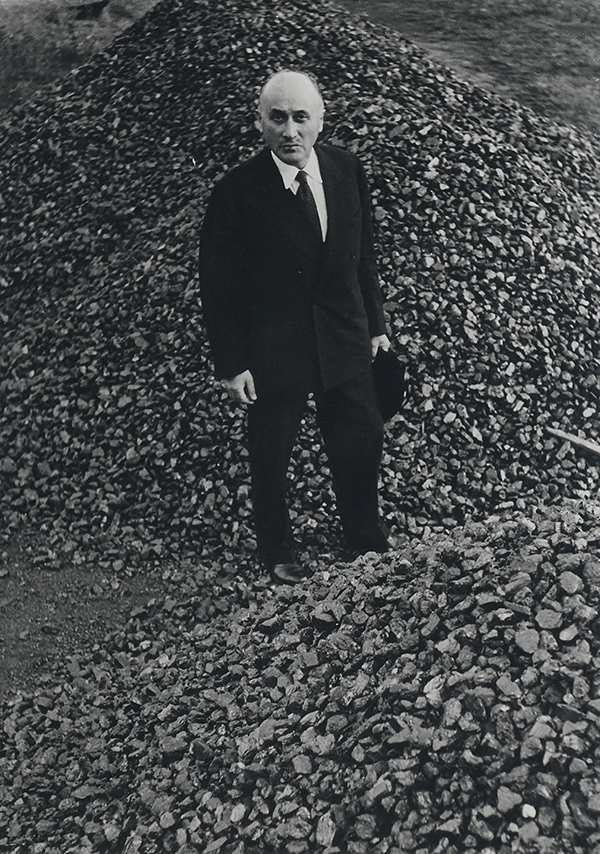

Altiero Spinelli, plenary session in Strasbourg, March 1984 | Photo Service of the European Parliament | © European Union – EP

Jacques Delors delivering a speech about his appointment as European Commission President at the European Parliament of Strasbourg in January 1985 | Photo Service of the European Parliament | © European Union – EP

To this approach –after taking stock of the failure of the revolutionary project advocated by the Manifesto – Spinelli preferred a constitutional method: he claimed the need for a European constitution based on a federal model, with a parliamentary assembly as the political space to discuss it, as has happened in all our countries, where the democratic constitutions were written either by a constituent assembly or by a parliament elected by the citizens for such purpose.

The constitutional position of Spinelli has appeared to be very relevant in the last thirty years of European history, and even before that, when he was a Commissioner and tried to persuade the Commission to follow a federal path for the construction of the European Union.

Video: The European Parliament drafts Treaty on the European Union: Spinelli – 14 February 1984 | © EP Multimedia Centre

Picture: Spinelli in the European Parliament, shortly after it adopted his plan for a federal Europe in 1984 | © EP Multimedia Centre

In line with this approach, the project of the European Parliament – approved on 14 February 1984– put the realization of the political unity of Europe before economic and monetary unification, while the Maastricht Treaty – far from constituting the embryo of a European federal power – put the achievement of monetary union before the completion of the economic union, leaving the creation of a political union behind on an undefined agenda with no content or timing.

According to the same perverse logic, governments imagined that the response to the financial crisis of 2007-2008 could come from a process that started with an incomplete banking union, to then move to budgetary union and finally to economic union, leaving democratic legitimacy once again only vaguely characterized in terms of methods and timing.

Finally, there is a statement by Spinelli on the three reasons for the relevance of the Manifesto to our times – after the turmoil caused in the second decade of the 21st century by the financial crisis, by international terrorism which arose and was active in Europe, by the desperate search for a better future for millions of asylum seekers and finally by the pandemic:

- the idea of the foundation of a European federation belongs to the current generation and not to an indeterminate generation far away in time,

- the action to carry it out requires a vast mobilization of public opinion but above all a movement organized according to revolutionary logic,

- and the line between political cultures no longer divides right and left, conservation and progress, but those who defend apparent national sovereignties and those who are ready to fight for a higher European sovereignty, that is, between the immobile and the innovators.

On the agenda for the future of Europe it will be worth going back to these analyses and recommendations, placing them in the context of a new form of international cooperation where the federal unification of Europe is a model of regional integration, through which it is possible to build a new relationship between our continent and the others, within the framework of a project for a new world.

Women for Europe.

A memoir of times and places of tenacious commitment

share

By Luciana Rochi 5

The distant memory of the Manifesto of Ventotene has gone through oblivion, occasions of awakening of interest and critical analysis – especially when the reasons for the realpolitik or instances of irrelevance of the role of the European Union have appeared so strong as to make us rethink the value of utopia. One of the “characteristic features of modernity”, wrote the philosopher Remo Bodei in the 1990s, would be “the narrowing of the space of experience and the lowering of the horizon of expectations”, in harder words “the bankruptcy of utopias and hopes”

(Bodei, 1995).

Federalist meeting in Monte Oriolo, August 1943. In the foreground, from the right: Elide Verardi, Ernesto Rossi, Enrico Giussani, Carlo Pucci, Guglielmo Ferrero, Clara Pucci, Bruno Pucci, Mario Alberto Rollier, Ada Rossi, Eugenio Colorni, Lorenzo Ferrero and Aida Ferrero | Photographer: unknown. © European University Institute 2021

Today, in looking at what happened in Ventotene in 1941 there is the “hard core” of the facts: at the peak of total war, a small group of confined anti-fascists had the intellectual and moral strength to design a future opposite to what was in progress – the Nazi-Fascist project of new European order. But despite this, today there is a renewed need for utopia: the desire to complete, beyond its current form, the project of a united Europe.

This is demanded by the return of nationalism and the impossibility for a divided Europe to move in the global world, in the presence of challenges of unprecedented proportions. For this reason, the return to Ventotene today must be an opportunity to focus on unspoken or not sufficiently remembered aspects or unpublished questions.

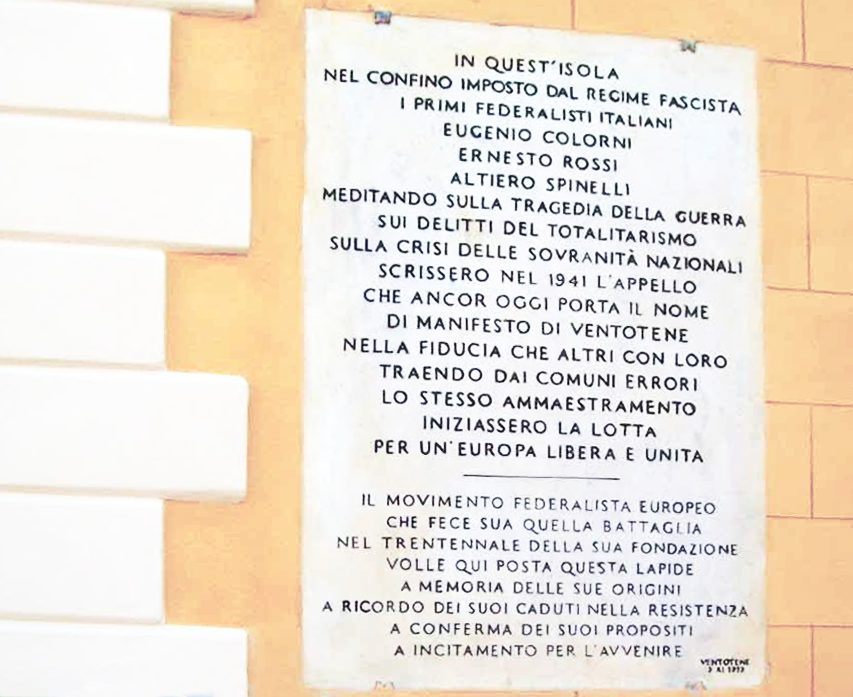

The plaque discovered on the island on November 3, 1973 celebrates Eugenio Colorni, Ernesto Rossi, Altiero Spinelli and the birth of the European Federalist Movement. The roots of the ideas developed in Ventotene go back over the years and cross Europe. Those names have so far occupied the entire space of public memory; as part of that European youth, who emancipated themselves between the Spanish war and the Resistance, as well as two women, Ursula Hirschmann and Ada Rossi, whose contribution was recognized was later recognized, and is still less visible in the collective memory. The enormous delay in recognising their role remains to be addressed, as with all women of the European Resistances.

Recent biographies speak of different subjectivity and experiences in the years of formation, of roads that are in fact distant, but with the original character of an extraordinary tenacity, up to the meeting in Ventotene. The irremovable existential and political-cultural refusal of Nazism and Fascism is deep routed; they arrive to action, as often in the Resistance, aligned to a man, since he has obscured the reasons for the commitment of many other women, relegating him to the confines of the space of “care”. In their case, they were significant male figures. It is difficult to escape the fascination of Spinelli’s creativity of thought and writing, of the wealth of philosophical contributions by Eugenio Colorni, of Rossi’s endless bibliography. In reality, the heroic death of Colorni and the importance of the political role of Rossi and Spinelli remain as symbols.

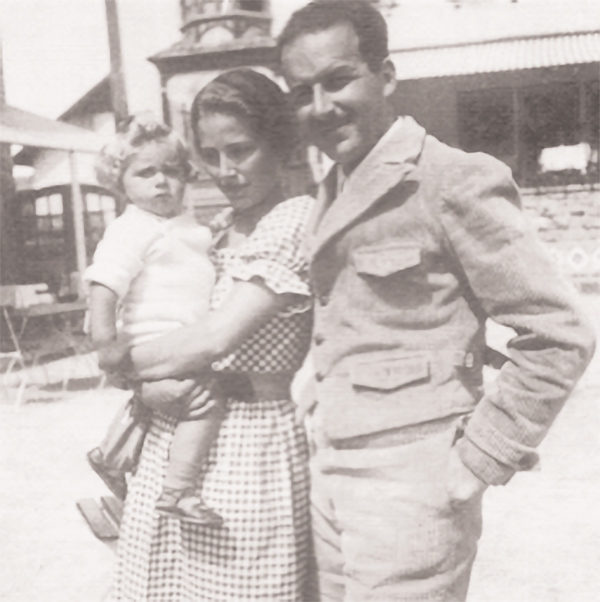

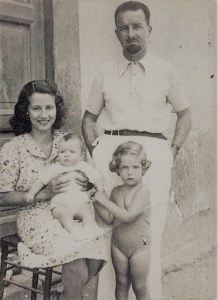

Eugenio Colorni and Ursula Hirschmann with their first daughter Silvia in Ventotene. Colorni was murdered by fascists in Rome in 1944. Hirschmann married Altiero Spinelli the following year. | © 2021· Fondazione Rossi-Salvemini

Ursula is a German jewess who rejected Nazism early and joined together with her brother Otto Albert in left-wing groups, learning about political conspiracy. She chooses exile from Hitler’s Germany at a very young age, the beginning of a pilgrimage in Europe – she will define herself as “senzapatria” -, a prelude to the cosmopolitan vocation, the essence of her Europeanism. Ursula’s figure is political, but has deep cultural roots, “very intelligent and very refined… the agreement with her could only be created on intellectual affinity”, recalled her daughter Renata Colorni in 2019. So it was for the short years of love between her and Eugenio Colorni, so for the long and intense relationship with Altiero Spinelli; alongside them an ideal and political maturation took place which distanced her from the initial Marxism. She had a generosity of feelings that made her want and raise six daughters. One of Ursula’s singularities is the inseparable relationship between the vocation for the “feminine” – love and motherhood, a spontaneously “different life” – and the struggle for universal values, which is solidified in the commitment to the Federalist Movement, to assume in maturity a new character: the choice of a common front of women. Among her papers remains the testimony of the versatility of a complex personality, on both intellectual and action levels (Boccanfuso, 2017).

Ada goes beyond the female stereotype of the time in choosing her studies: she graduates in mathematics and adds to her passion for science the anti-fascist choice, all-encompassing from the meeting with Ernesto Rossi, whom she married in 1931. In the substantial nucleus of letters from Rossi’s prison, there are a thousand traces of the intense dialogue between them throughout the Thirties, testimony of the process of elaboration of ideas and political planning. The network of clandestine relations that Ada manages, an invaluable link between prison and free anti-fascists, is astonishing. Ernesto entrusted messages to her, Ada sent transcripts of passages on economics and mathematics lessons to him, which were also used by fellow prisoners (in the absence of paper and pen, they wrote exercises on the glass with their finger). Ada supported him, she was attentive to the international situation, towards the end of the Thirties – the Spanish War, the explosion of nationalism up to the war…

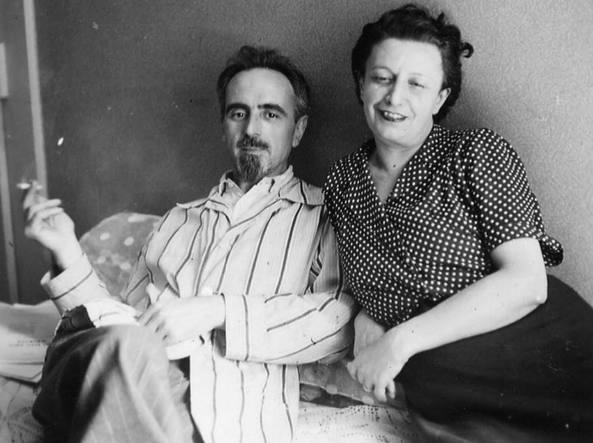

Ernesto and Ada Rossi in Geneva with two young friends: Guido Majno and Carlo Donati (“Donatino”). Photographer: unknown. Copyright © 2021 · Fondazione Rossi-Salvemini

Vittorio Foa, one of Ernesto’s companions, remembers: “When she came to see Ernesto, it was for all of us like entering into communication with the world”; she transmitted “a vital charge that represented all possibilities” (Braga Vittori, 2017). Their emotional bond was of great intensity; the marriage, celebrated in prison in 1931, will cease to be “putative” only from 1939, according to Ernesto’s playful definition. After the death of her husband, she becomes the custodian of the precious Salvemini-Rossi archival fund, which has gone through political controversies, now safe in Florence.

It took time to break the shell of “wives of”, which has left the protagonism of Ada and Ursula in the shadows in the history of the federalist utopia. Emma Bonino, commemorating her, wanted to ignore the man with whom Ada had shared hopes and struggles; many sources give her the image of her intelligent, protective, tireless relay companion. Even an enlightened mind like Gaetano Salvemini pays her esteem and affection by virtue of the care with which he supports his beloved “puppet” – Ernesto’s affectionate nickname, in “Letters from America” (Salvemini, 1967). And it is she herself who supports the reasons for Salvemini’s praise, in 1945: “I promise that I will always watch over Ernesto and modestly help him in my possibilities”. It would be anachronistic to demand the language of current cultures. Rather, the apparent contradiction is an opportunity to extract new questions from such distant and singular stories. An example: the polysemy of curate, a key concept for a description of the experiences of Ada and Ursula, is today a ground for questioning society as a whole, the feminine and the masculine, about the future.

Signs of their presence and action in Ventotene remain in Spinelli’s writings, in letters, literary works, as well as papers in various archives.

Ventotene, the small island with the “loud voice” – the wind that sweeps its streets and “makes them sound like organ pipes” (Paganelli, 1975) – hosted an enormous number of confined people: eight hundred, with three hundred guards, between 1942 and ’43. Until the 1990s it was almost devoid of physical traces of their passage: the barracks were destroyed, just “a small plaque on a piece of white wall”; an absence that made the “cancellation of the memory of confinement” “disturbing” (Ramondino, 1998). Not even the names of the two women. They met in Ventotene in 1939, when the police of the fascist regime authorized them to join their husbands, Ursula with her first daughter in July, Ada in December, in a climate weighed down by the material difficulties of the life of the confined, struggling with the scarcity of food and conflicts between political groups. Marriage cohabitation begins in Ventotene for Ada and Ernesto. From the diaries of Spinelli and from fleeting references in the diaries of other confined, images of one or the other appear, of Ursula also the beauty – “Really, halos and nimbus around her body” -, which corresponds to the description of Colorni’s sadness on a day when the “blonde wife is about to leave”. (Paganelli, 1975).

It was the time of confrontation and the progressive elaboration of the theses that will lead to Manifesto, in the first draft completed in the summer of 1941. Without a philological analysis of the document, an attribution is impossible. If in not even one line of the texts signed by Spinelli, Rossi and Colorni between 1941 and 1943 there was the hand of the two women, the time of the internal dialectic of the two families, in presence or from afar, is part of the path of thought that converged in the thesis. Although of different origin, it is legitimate to speak of their preexisting pro-European vocation. Throughout the Thirties, Ada’s house in Bergamo had been a school of anti-fascism for a group of young people, who would join the Resistance in 1943, in the formation of Justice and Freedom. In Rossi’s letters to his wife during the period of detention at Regina Coeli, common readings are cited, rich in “teachings […] to better put into concrete our ideas on the perspective of a federalist organization of Europe” (Franzinelli, 2001 ).

Of Ursula, the “enlightenment, violent and definitive” that had made her abandon the Marxism and communism of the years in Berlin and her exile in Paris, between 1933 and 1935, was the result of that impatient “waiting for the anti-Hitler revolution” Berliners had not wanted to try. The philosophical and political dialogue with Ernesto’s secular liberal socialism allowed her to reach a balance, but by her, Ernesto was led to move more quickly towards action; in emphatic language, she wrote to him that it was time to “put life at the service of history”. It is not possible to go beyond a “circumstantial paradigm”, but we seem to understand that her exceptional experience as a Jew and dissident, in the Berlin of the dark moments of the Reichstag fire, and then of deracinée in radically formed the abandonment of the absolute sovereignty of the nation-states for the European federation. Not having a language, having lost heimat, not having really lived even her Jewishness had made it “easier for her to be European”, she writes in her autobiography (Hirschmann, 1993).

Portrait of Ursula Hirschmann (circa 1943-1945) | © European Federalist Movement 2021 / © 2021 mfe.it – Services

Both enter and leave the places of confinement, after Ventotene, in Melfi, Ada in 1942 condemned herself for conspiratorial activity, Ursula to follow her husband, when he was transferred there. They are the ones who weave relationships with the Italian anti-fascist conspiracy, of which they had already experienced in different forms, and circulate the Manifesto in Italy. We do not know with what stratagem Ursula’s husband left the island; the exceptional nature of the company also fueled the invention of imaginative hypotheses. From the biographers of Ada Rossi comes the curious image of her who “sharpened the pencils with which Ernesto copied Manifesto in light paper and with a tiny handwriting”, which does not contradict the intent to document her contribution which is anything but subordinate. As a matter of fact, in Ada’s personality, it is said, the courageous independence of thought and action coexists with the unawareness of her own role: “political animal almost without knowing it”, whose commitment is “natural continuation of care tasks” (Braga, Vittori, 2017).

The outcome: the first diffusion and the beginning of a debate, for the first time in the history of Italy (perhaps of Europe) with the ambition to go beyond the level of ideals. The task of recovering the historical roots and civilization of the European population was measured against the political ties, with the lesson of the harmful consequences of nationalisms. There was – Ursula and Ada had direct experience – the hostility of the communist confined, in the struggle of Europe between the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact and the war. The Communist group itself was torn apart, as the solitary walks of Camilla Ravera and Umberto Terracini, marginalized after the expulsion from the party, recount in the memoirs of an exiled person. From the correspondence between Rossi and Spinelli, “Empirico” and “Pantagruel”, (Graglia, 2012), from the writings of Colorni and from many pages of Spinelli, the loneliness of the Europeanists appears. The network of relations between Ada and Ursula favors socialist and shareholder groups, from which adhesions came, together with painful ruptures of ancient political affinities. Altiero’s sisters Fiorella and Gigliola also took part in the dissemination work, who will join the Partisan Action Groups. They secretly provided the printing of the first Manifesto, then of the modified versions and other texts, in Bergamo, Milan and elsewhere. In the documents produced by Hirschmann in the two-year period 1941-1943, almost all private, one can read clear analysis, which explain the origin of an apparently outdated utopia in 1941, while Nazi-fascism was winning. In reality it would have arisen precisely from the catastrophic course of the war; leaving Europe in the hands of the nation-states meant giving up the future.

When the Fascist regime collapsed in the summer of 1943, but it was still in secrecy, the Federalist Movement was born. The chronicle of the preparation of the founding meeting, on August 27 in Milan, at Alberto Mario Rollier’s home, saw an enormous organizational effort, especially by women. Among the participants were notable names from the different political orientations of Italian anti-fascism; some, such as Colorni and Leone Ginzburg, soon became victims of the Nazi-Fascist repression. The basis of discussion was Spinelli’s Federalist thesis, not the Manifesto. From the north of Italy in 1943, the attention is turned to Europe: Ernesto and Ada Rossi, Ursula, the three daughters (born from the marriage with Eugenio Colorni, long overdue) and Spinelli, move to Switzerland, crossing the border adventurously. Since then and forever, the two will be linked by a great love, set-off in 1944 by marriage, after the assassination of Colorni, in Rome, a few days before the Liberation. From this moment on, a European history of hopes and disappointments begins for the Movement. Norberto Bobbio will write that federalism and the Resistance are welded together through multiple “cultural and political convergences”, so much so that “no one today can make the history of the Resistance without the federalist perspective” (Bobbio, 1991). The Resistance is European. German anti-Nazis, French anti-fascists and other countries are progressively joined by the increasingly large and efficient organization of the Movement, whose fortune has a karstic evolution. The newspaper “L’Unità Europea”, an organ of the Movement, was also born. Spinelli attributes to Ursula the commitment for editing and printing.

The next step was a conference in Geneva, the first experiment of discussion with important European federalists, in May 1944, again thanks to the fundamental commitment of women, Hirschmann the only intermediary with the German component. The outcome was not exciting, but the results obtained in the liberation of France led to a third appointment, in Paris, in March 1945, where a “Comité français pour la fédération européenne” already existed.

Italian delegates were only Altiero Spinelli and Ursula Hirschmann, alongside a bouquet of French intellectuals, including Albert Camus. The enthusiasm for the high level of the debate was short-lived; no turning point, if anything, a setback also in Italy. Scrolling through the editorials of Camus himself in “Combat”, a newspaper born from the Resistance and edited by him, the distance between the interests of the Italian and French federalists is evident, these last concentrated on the fate of France in the post-war, on the reconstruction of bilateral agreements in view of peace treaties, not on the promotion of federalism. Camus realistically foresees the crystallization of the two blocks and the competition between the most powerful winners, the Soviet Union and the United States (here we find an assonance with previous analysis by some Italian pro-Europeans) and, if anything, cultivates in another utopia: a capable universalism to guarantee international democracy (Camus, 2010).

It is worth remembering the meeting, crucial for the actual realization of the conference, between Albert Camus and Ursula, for what it reveals about her. Without having read the books, with these and other expressions he painted the character: “A great player who would play themselves rather than abandon the game” or “A happy Sisyphus, who was able …to transform their duty into passion”. The immediate intellectual and instinctive understanding, which seems to matter more to her than the awareness that Camus would have disappeared from the horizon of the Ventotene project, will be highlighted in her story. In 1947 Camus dreamt of, yes, a Europe “of people, free from the myths of sovereignty”, but after the Paris Convention he had ignored Spinelli’s requests; in the Treaty of Rome of 1957 he saw only “about twenty snares” that “do not make it breathe” (Camus, 2012).

In the tortuous paths of the Federalist Movement, in the Europe of the cold war, there was still the passionate and vigilant presence of these two extraordinary female figures, Hirschmann, despite the six daughters being raised. During the time of the common life of the two couples, the male-female alliance represented an added value, which would be very interesting to deepen.

Something is captured by a glance at the years of full maturity. After the painful separation from the common commitment with Altiero, a member of the European Parliament since 1970, Ursula founded “Femmes pour l’Europe”, stating the feminism of the Seventies in the European dimension. In EFFE magazine she denounced the “bad conscience of the rulers [and the] weariness and dullness of European politics where obviously – as in all politics – women are absent” (Hirschmann, 1975). Political disappointment, along with inner torment, is evident between the lines of autobiography, interrupted when an illness prevented her from speaking and writing, without ever stopping her completely.

After the death of her husband (1967), Ada experienced a new period of political activism in the Radical Party. She was over seventy, Ursula sixty years old and they invented “something entirely new”; as should happen to politics, the philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote in 1967 (Arendt, 1995).

Ursula Hirschmann

share

By Silvana Boccanfuso

Historian, author of

Úrsula Hirschmann, una donna per l’Europa

Born in Berlin on September 2, 1913, the eldest daughter of a wealthy middle-class family6, Ursula Hirschmann, not yet twenty, leaves her city to escape political and racial persecution. She will see Berlin again only in the 1950s; she will never live there ever again. Italy will be her home, Europe her homeland. Refined intellectual and persevering political activist, her history is inextricably linked to that of European federalism since the drafting and dissemination, at the beginning of the 1940s, of the Ventotene Manifesto.

Portrait of Ursula Hirschmann

| © European Union, 1995-2021

For the realization of the European federation Ursula fought all her life, even in those times of crisis, economic or political, in which the idea of a united Europe has not been particularly popular. The commitment is up to the end of her days: when Ursula Hirschmann died at the age of seventy-eight, in 1991, she held the position of president of the Roman section of the European Federalist Movement.

So much conviction in a project can only be explained by starting from the beginnings of Ursula Hirschmann’s political commitment. It is in Berlin in the 1930s, between the Weimar Republic and the rise of National Socialism, that little more than a teenager, Ursula approaches politics by enrolling with her brother Otto Albert at Sozialistische Arbeiter-Jugend, the organization youth of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). The weakening of democracy, the now evident social contrasts, the spread of violence, the obstinate blindness and political inactivity of the liberal bourgeoisie also demand action from the young. Ursula and Otto do not hesitate. The Socialist Youth is, above all, a discussion group but it still gives the young woman the opportunity to witness firsthand the internal political debate of the SPD – and of the left in general – at a time when left-wing parties, displaced by events, are looking for establishing a course of action (which will later be “inaction”) to counter National Socialism. In June 1933, the arrest of a friend and comrade in struggle of the Hirschmann brothers by the Gestapo and the discovery of a notebook with the names of the members of the Social Democratic youth gave Ursula the idea of leaving Germany for a while. Destination Paris. In her escape, which took place in July, Ursula is accompanied by a young Communist friend from university with whom she will share, in love, the first months of her stay in Paris. The young woman lives expatriation with the romantic unconsciousness typical of her young age, perhaps because she is in love, or simply because she is sure of returning to Berlin soon, convinced of what the left party was preaching, “that Hitler would not last long” 7. On the other hand, that step out of Germany will be irreversible. 1933 is the year in which Hitler’s grim racial policy takes shape with the promulgation of the first racial laws and Ursula’s mother, worried, invites her two expatriate children not to return to Germany.

In Paris, Ursula spends time with anti-fascist and anti-Nazi exiles; she turns away disappointed from social democracy; she approaches the Communists, taking distance from them, as well as criticize them. After two years, in search of truth and political clarification, she wrote to a friend from the time spent in Berlin, a young Italian philosopher she met in the winter of 1932 8, Eugenio Colorni.

Eugenio invites the young woman for a short vacation in Trieste, where he lives and works as a philosophy teacher in a teaching institute. The friendship there in Trieste, in that spring of 1935, turns into love and at the end of December of the same year, in Milan, Ursula becomes Mrs. Colorni. Eugenio, militant anti-fascist, director of the Socialist Internal Center, was arrested on September 8, 1938. However, there is no evidence to support the hypothesis of Mrs. Colorni’s actual involvement in her husband’s anti-fascist activities, therefore Ursula is not prosecuted, and when Eugenio, after four months in prison between Varese and Trieste, is sentenced to five years of confinement to be done on the Ventotene island, Ursula was given the permission to follow her husband on the island, since she was as a foreigner with a small child 9 and without any family support.

Colorni and Ursula with their daughters Silvia and Renata. Ventotene,1940 | © Fondazione Rossi-Salvemini.

Ursula settled permanently in Ventotene at the beginning of July 1939, determined to bring the family unit back together. The other two daughters of the couple, Renata and Eva, are conceived in Ventotene. But, above all, in Ventotene, Ursula’s anxiety for political action finds a concrete and definitive form through which to express herself.

In the Pontine islet some intellectuals meeting “recognize each other”, to use the words of one of them, Altiero Spinelli. Ernesto Rossi, Altiero Spinelli, Eugenio Colorni, Ursula Hirschmann, sporadically Ada Rossi (Ernesto’s wife), who lives in Bergamo and arrives on the island only for a visit, and very few other confined compare ideas, experiences, ambitions and their vision of the world. From the encounter, sometimes clash, of this intelligence comes what has gone down in history as the Ventotene Manifesto, the programmatic document of European federalism of Italian origin. A main basic idea: the overcome of national sovereign states and the creation of a European federation as the only possible form of peaceful coexistence in Europe.

For the realization of this ideal, a true European unity, Ursula begins to fight immediately. Benefiting from fewer restrictions on movement, the young woman manages to bring the Manifesto to the continent transcribed on small cigarette papers hidden in the fur pillowcase, and to spread it. Ada Rossi also plays the same role, as well as Altiero’s sisters. In 1941-1942 these women began a work of proselytism – which continued in geometric progression – thanks to which it was possible to organize a meeting of the neo-federalists immediately after the fall of fascism in a few weeks. The meeting was held at the end of August 1943 in Milan, in the home of the Rollier couple. It is the birth of the European Federalist Movement.

The meeting has another value for Ursula. The marriage with Eugenio ended some time ago and in the Rollier home Ursula sees Altiero after two years 10. Since then, they will never break up. They will be companions in life and in struggle; a solid, affectionate, passionate couple, intellectually and politically complicit. Together, they will fight the thousand federalist battles inside and outside the MFE.

So, the key to understanding the solidity of Ursula Hirschmann’s pro-European commitment lies perhaps in that summer day in 1933: in the estrangement from Germany, in not returning there and in the inevitable gradual loss of her own national identity. Here is how Ursula herself talks about it in her autobiography, with the explanatory title Noi senzapatria:

[…] I am not Italian although I have Italian children, I am not German although Germany was once my homeland. And I am not even Jewish, although it is pure chance that I was not arrested and then burned in one of the ovens of some extermination camp […] We déracinés of Europe that we have “changed borders more times than shoes” – as Brecht says, this king of déracinés – we too have nothing to lose but our chains in a united Europe and therefore we are federalists.

The lack of roots, the absence of a homeland, the rejection of any form of nationalism and of any race as a dividing line between men: over the years, the national belonging theme cannot but weave together in Ursula with the most delicate reflection on what it means for her to be Jewish. In an exchange of letters with Natalia Ginzburg 11 in the first half of the 1970s, Ursula Hirschmann tackles the subject with the intellectual honesty and incisiveness that are her own, clarifying that her connection with Judaism is neither of religion nor of race, but it is the feeling of being a “stray”, proud of being one. These are the weeks following the Munich massacre by “Black September” and Ursula, in the fervor of the debate that ensues, does not hesitate to firmly reaffirm her lifelong belief: not to be able to accept any nationalism, not even that as a Jew of Israel, certain that “even in Israel it will bear the poisoned fruits it has given everywhere: conspicuous successes, less conspicuous but deep wounds, a spirit of revenge, revenge and so on until new genocides” 12.

Ursula Hirschmann arrives at her full maturity and she is not afraid to sum up her intellectual reflections, not only political but also personal. Also in Natalia Ginzburg, Ursula confides the conclusions she reaches by critically reconsidering her own life as a woman also in the light of reading feminist texts. It is precisely feminism, to which Hirschmann never completely yields, the source of inspiration for Ursula’s most important pro-European action: the creation, in the mid-1970s, of the initiative group Femmes pour l’Europe.

Created by combining federalism and feminism in an original way, Femmes pour l’Europe was born in response to a period of individual and collective crisis. It is the attempt of a woman engaged in the battle for the United States of Europe since its inception to give new and renewed operational vigor to an idea – that of a united Europe – which not only had lost credibility over time, but which risked collapsing definitively under the weight of the severe economic and financial crisis of those years. The fact that claims linked to gender discrimination are grafted onto this primordial objective is the inevitable consequence of a social commitment to women that the movement cannot fail to assume given the historical period in which it is located, and which allows Ursula’s idea Hirschmann to survive them, albeit in different organizational forms, thanks to the political activism of other women. Fausta Deshormes la Valle and Jacqueline de Groote will be the two main architects of the change in a new form.

Therefore, the most important moment of Ursula’s commitment to European construction – understood as her own and original contribution to the federalist cause – is not to be found in the 40s, the years of Manifesto di Ventotene to be clear, but in the much more recent 70’s.

Femmes pour l’Europe had short life because of the unexpected disease of Ursula 13 occurred only little months after the official constitution of the group, happened to Brussels 14 on April 24, 1975. However, there is a lot to be said about it. And to be clarified. Here, I will limit myself to reiterating two important concepts.

First of all, by interpreting the birth of the initiative group in terms of Ursula Hirschmann’s adhesion to the feminist movement would be a mistake because Femmes pour l’Europe was the result of numerous considerations of a political and personal nature that are more articulated than a simple acceptance of the feminist movement. It is true, in fact, that the intuition that gives rise to the project is the idea of “channeling the feminist dynamism of our times towards the federalist struggle” 15 but it is also true that Ursula, from the very beginning, appeals to all European women regardless of their political beliefs or social commitment.

Secondly, that it was a federalist action, as clearly expressed in the two programmatic documents of the group, Appel aux femmes d’Europe and Lettre d’accompagnement à l’ “Appel aux femmes d’Europe”. The women of Femmes pour l’Europe do not ask Europe but they act in support of Europe! Ursula’s logic is compelling: if Europe collapsed under the ax of the general crisis, a return to national policies would cause an economic, social and cultural regression from which all Europeans would suffer, but first of all women. In fact, being their most recent conquests, they would be the first to be sacrificed. Hence the need for women to take an active part, with a political weight corresponding to their numerical importance, in the battle for real European unification. And their political weight is decisive: it is only with the freshness, imagination and courage of new forces that a true, future European democracy will see the light.

And this still holds true today.

Ventotene integrated project for the recovery of the Santo Stefano prison

share

Vision

Ventotene and Santo Stefano, a single city-hall, two islands that shared the fate of imprisonment and confinement also linked to political dissidence, freedom of thought and the construction of democratic and pro-European principles.

Ventotene view from Santo Stefano | Picture: Francesco Collotti

Ventotene, “Cradle of Europe”, where in 1941, from the confinement of the fascist regime, Altiero Spinelli, Ernesto Rossi and Eugenio Colorni founded the Manifesto “For a free and united Europe”, those United States of Europe which are an increasingly topical target.

Santo Stefano, where for two hundred years since 1795, the Bourbon prison recluses first, alongside the common inmates, patriots, jacobins, Risorgimento fathers, and then, during the unitary Italy and the twenty years Fascist, dissidents and fathers of the Italian Constitution who were guide, since the Fifties, for the enlightened director Eugenio Perucatti.

In both these Italian islands, located in front of the Tyrrhenian coast and on the border between the regions of Lazio and Campania, we can recognize an explicit, clairvoyant and shared critique of the totalitarian experience that marks out the continental twentieth century after the First World War, thus as a weaving of humanistic principles and institutional political visions that show, after eighty years, their relevance and their modernity.

Preserving and passing on to future generations the memory of these places, which also due to territorial marginality have incurred phenomena of abandonment and oblivion, is an essential process and a constant commitment.

In the program for the recovery of the recent historical memory of these places, three main principles are identified that can inspire the project for an integrated and possible vision of Europe.

Human rights – Freedom of action and critical thinking, human dignity, the rule of law, solidarity,

justice, international cooperation. As well as the shadows and ambiguities that run through the history of the conception of the sentence between reparation and rehabilitation that accompanied the prison’s organization.

The history – «Remembrance», non-rhetorical coexistence of present and memory, testimony that preserves the mystery of human lives and of time and that imbues the ways of conservation, of the redevelopment of the monument that becomes a stratified document over time.

The mediterranean – Complex ecosystem, historical presence, set of millenarian places and civilizations that have been stratified in them, custody of a tangible and intangible heritage and an inevitable challenge for a sustainable future. A reading inspired by Fernand Braudel’s long-term vision and by contemporary social, demographic and naturalistic challenges.

Concept

Today, the arrival in Santo Stefano is both suggestive and challenging. It is a long route that stretches from Rome towards Formia, then by sea towards Ventotene and then from Ventotene with small boats towards the prison island. From Naples, it entails the passage from the Phlegraean Fields and then a path from Procida and Ischia to Ventotene.

The arrival on the island is – for a visitor of average athleticism – quite complex, a quay made up of modeled rocks, beaten by the undertow, a climb on hand-chiseled, disconnected and steep steps between basalts dug out or overlooked by caves and ravines. Remains of corroded artifacts and technologies, writings and graffiti of prison guests, and then the ascent under an often beating sun, among scents and glimpses of the landscape that stretch over the sea and Ventotene. The arrival at the prison with its abandoned and dilapidated buildings leaves an impression of “mort – subìte”, of hasty and definitive abandonment as from a place that has exhausted, due to an excess of ferocity, its meaning and purpose.

The imposing and eloquent panoptic (a model structure conceived by the architect Francesco Carpi, only a few years after Jeremy Bentham’s ideal prison) reaffirms, at the same time, the strength of the original project and its inability to hold on to the present. It re-launches an imprint of horror and power. The path on the road that runs through part of the perimeter of the island up, up to the cemetery, opens up to a dimension of meditation, of relationship with the power of nature, of the rocks, of the sea, of the sky, which is found in the abandoned cemetery, with its worn crosses lying on the ground, as a point of further concentration and thought.

The recognition of the character of this place and its history was the starting point of the project, which has been set, since the beginning, the goal of a “remembrance” capable, however, of representing an opportunity to “presence” and therefore to relaunch towards the future. A goal that deserves, in its intonation, a brief clarification.

The “remembrance” does not coincide with the erudition, it is not resolved by an antiquarian dimension, nor with the abstract consideration of “intrinsic”, nostalgic or worse historicism values, of memories. Remembrance, as Walter Benjamin suggests, is not articulated on a linear and empty time, but a time in which memory and present intersect. “The time that fortune-tellers questioned, to steal from them what was hidden in her womb, was certainly not experienced by them either as homogeneous or as void. Those who keep this in mind perhaps come to get an idea of how past time was experienced in remembrance…. In it, every second was the small door through which the messiah could enter” (Thesis XVII B).

In this perspective, remembrance is the path that leads to the qualification of “presence”.

The place that this project is called to constitute must not be a memorial for its own sake, but the living opportunity for a conscious experience of the presence. What does it mean to really be “present”? It is the result of an alchemy that allows you to undertake a non-rhetorical coexistence of present and memory, to be held in measure, as a fundamental act of culture. The Latin prae-sum indicates, in the first place, the ability and the act of to stand in the presence of. Being in front of something, or someone, literally implies a stance: standing in front of, implies a relationship of reciprocity. What lies before us, literally, concerns us – and therefore inevitably transforms us.

Giving life to a place of presence is equivalent to defining a non-random choice: a space of awareness, and of radical questioning about what really concerns us, as men and women and as a community. In this sense, inevitably, and in the highest sense, a fact and a political act.

In this case, due to the strong and immanent presence of a memory of confinement and pain, remembrance also implied a confrontation with a possible solution to the heaviness of this memory. Not so much in the sense of its “redemption”, but rather of its solution: the possibility of dissolving the horror that led to the abandonment of this place, making it somehow compatible with the present and with the future.

This principle has therefore determined some fundamental choices: the overall experience that is intended to favor with the visit, the quality and limit of the renovation and refurbishment interventions, the nature of the museum and service structures, the usability of the panoptic and the possibility of inserting in it the work of one or more great contemporary artists, the re-connection of the cultural capital represented by the panoptic and its history with the natural capital of the island.

The project – as regards the island of Santo Stefano – was therefore articulated around some fundamental issues: