share

Representing our civil and civilly organised society is at the heart of democracy. It is the foundation of all systems of rights and freedoms and guarantees the separation of powers. Citizens have an opportunity to express themselves by taking part in elections in which candidates compete to represent the people, and regular universal suffrage reflects the will of the people. All societies are aware of this, although it can sometimes be overlooked by the powers that be or because of an extreme desire to amass power.

The aim of this publication is to take a look back at how supranational elections have unfolded across Europe, which is an interesting and necessary historical exercise. The book is the result of a new collaboration between the European Observatory on Memories (EUROM), led by the Solidarity Foundation of the University of Barcelona, and the European Parliament’s Jean Monnet House. This new volume is of high academic value and features an informative style and a wide range of different themes, enriched by the experience and expertise of the contributing authors.

As 2024 will be such an important year, with the tenth European elections taking place – a crucial event given the current trends on the European stage – we need to reflect on the history and political evolution of these supranational elections. Because we believe that democracies are a process of popular struggles that have been waged throughout history. Because we believe in the federalist vision of a united Europe that emerged after the horrors of the world wars. Because today’s challenges are testing Europe, while it still remains strong despite the many crises that it faces year after year and which affect everyone in Europe.

Participatory democracy reflects the will of the people and is a fragile system. It must, therefore, be safeguarded and protected today, by learning from the past and addressing the challenges of the future. State arenas and large supranational institutions are still facing multiple crises and conflicts that are reminiscent of the past. In 2024, a new round of European Parliament elections will be held, with projections of low turnout and, once again, a surge in far-right populism. Plurality is undoubtedly one of the foundations of democracy, but we must be wary about crossing red lines between democracy and totalitarian attitudes or even dictatorships. They are not only nostalgic reminders of times past when people lived without freedoms – they also put forward reforms and programmes that pose a threat to the democratic and parliamentary system itself.

When we look back over our more recent past, these representative and participatory agoras promote a political, social and, ultimately, ideological debate that makes us grow as societies with rights. For this reason, these spaces must be protected and defended. The history and – plural – memories of past conflicts often underpin today’s debates and political struggles in a forum where respect, social justice and civic freedom must prevail.

Defending a plurality of realities, identities and democratic memories, which are considered a right, is the responsibility of our state and suprastate institutions. It would be dangerous to move towards non-democratic spaces, given their capacity to persuade people and how this would mark a backwards step for rights and freedoms. The founding fathers and mothers of the concept of a united Europe warned against this, in the wake of the horrors of the Second World War. Today, as we face new challenges as part of more plural and inclusive societies, we must continue to defend justice in diversity.

I would like to thank the readers for their interest in this subject; all the authors for their wonderful contributions; the editorial team for their excellent work; colleagues at the Jean Monnet House for their commitment to the memory of today’s European Union; and the European institutions for their support as we carry out our mission of looking back at the past so that we can examine the present with the perspective of history. I hope you enjoy the book!

JORDI GUIXÉ

Director of the European Observatory on Memories (EUROM),

University of Barcelona’s Solidarity Foundation

share

Celebrating the 10th election of the European Parliament is a political act that tells us much about the essence of the process of European unification: its successes, its still unresolved knots, and, above all, its nature as an experiment in building supranational democracy. There could not be a more opportune historical and political moment to propose this analysis and to reflect on how the European experience can help us on a similar path at a global level, i.e. to create the necessary conditions for the emergence of global democratic institutions, an indispensable step to enable humanity to govern itself in the age of interdependence.

European federalists proudly claim to have been in the vanguard of the battle for a European Parliament that would be directly elected by universal suffrage. Not only had they mobilised politically since the mid-1960s, leading up to the popular initiative law, passed in 1969, establishing that Italy would unilaterally elect its European Parliament representatives by universal suffrage, but they also made a significant contribution in terms of vision and analysis1. The direct election of the European Parliament, from the federalists’ point of view, was the change that would trigger a constituent process, leading Parliament to claim the democratic powers that, in democratic states, are normally attributed to the parliamentary bodies that represent their citizens. This would trigger an institutional evolution, in the supranational and federal senses. It would also force politicians to mobilise at the European level, to fight for and gain power that would increasingly resemble a form of state power. Moreover, in terms of values and ideals, it represented the first example of an exercise in supranational democracy, calling on the citizens of (then) nine integrated but sovereign countries to elect their representatives to a common parliamentary assembly. In the ever-evolving process of European unification, the direct election of Parliament was, therefore, a turning point that forced the European Community to pick up the political threads that had been cast aside after the failure of the European Defence Community and the revival of the European project with the 1957 Treaties of Rome.

The real driving force behind European integration has, in fact, always been political. The revolutionary project from which the European Coal and Steel Community emerged was designed with supranational institutions that anticipated a federal structure and an instrument to create ‘common foundations for economic development as a first step in the federation of Europe’2. Without this project, the conditions for progress towards integration would not have existed, even within the common market. The poor performance of the European Free Trade Association, compared to the European Community, says a lot about the added value of the European project, despite the decision to neglect the goal of political unity and to leave the levers of sovereignty and direct relations with citizens in the hands of the Member States. The political project was therefore the political driving force that also propelled the integration process of the common market. However, at the same time, the ambition intrinsic to the project, combined with the weakness of European states, individually, and the need to find ever closer forms of union, led to the construction of the common market itself clashing with the need to increase EU competences and to find common forms of political management, if not yet governance. In this sense, the decision to call upon European citizens – at the time still simply citizens of their respective countries – to elect their common political representatives permitted the governments to acknowledge the deeper reality of the European project and, at the same time, created the instrument that helped it to evolve in a truly supranational direction.

The history of these 10 elections, explained and analysed in this book, and the history of the 45 years of integration that have elapsed since the first European election in 1979, have confirmed the predictions and theses of the federalists, but have also witnessed very strong resistance on the part of the Member States to sharing certain areas of political sovereignty. This resistance led them to generate a system that strengthened the intergovernmental method – precisely in the face of the need to expand common policies. Decision-making mechanisms thus became exponentially more complicated, and certainly not only, as many believe, because of enlargement, although this also had a strong influence.

First of all, the European Parliament constituted a point of no return with respect to the issue of Europe needing to have a government of a federal nature, and therefore one that is supranational, sovereign in its sphere of action and democratic, in that it is accountable to its citizens and directly legitimised by them. Its very existence and the logic it has triggered make it impossible to remove the issue from the European project, despite resistance and opposition from many national governments and parts of the EU.

The European Parliament has also effectively fought on two occasions to compel, first, the European Community and, later, the European Union to make political and institutional leaps in a federal direction. This happened in the first legislative term, under Spinelli’s leadership, as recounted in one of the essays published in this volume, when Parliament was still a consultative institution with the sole power to reject the Community budget proposal. The second occasion was during the parliamentary term ending in June 2024, following the process triggered by the Conference on the Future of Europe. We will reflect briefly on that moment at the end of the preface.

With the transition to the European Union and the considerable development of the Community system linked to the single market, alongside the requirements arising from the new international framework, Parliament has also acquired some political competences, on matters related to the single market and competition, and some, albeit very partial, supervisory power over the European Commission. However, it does not yet have the powers that are due to an assembly elected by the citizens, precisely because the European Union is not a federal Union. Therefore, despite transnational lists, it is not elected on the basis of a uniform electoral law throughout the Union, a factor that weakens the Europeanisation of the electoral debate. In addition, it has no powers of legislative initiative, taxation and budget, and it does not yet have oversight over the European Commission.

This is why every European election should be, firstly, a test of the political direction that voters want the European Union to take on matters of its competence, whether towards the right or the left. Secondly, given that these matters of EU competence do not concern fundamental issues affecting political sovereignty – from foreign policy and defence to economic policy and the budget – the elections should also be a test of the will to complete the process of building political unity and to give Parliament the powers that would allow it to effectively represent citizens and their political will, as laid down in the Treaties.

In this regard, as already mentioned, during the legislative term ending in June 2024, Parliament took up the baton of Altiero Spinelli when it drew up proposals and provided tools to reform the Treaties and to make concrete progress on the road to political union. The decision to convene a Convention for the revision of the Treaties is now in the hands of the governments. They are trying to put the brakes on it, in an information vacuum and in an absence of public political debate, both of which are detrimental to the value of the parliamentary institution and undermine the importance of Parliament’s request to trigger the Treaty reform on which the future of our continent literally depends.

That is why we would like to conclude this preface to the Ten Elections volume with the wish that the 10th European elections may become a moment of European debate on the future of the European Union and on the achievements of the outgoing Parliament in this regard, so that we can embark on a new period of European unification that will provide a blueprint for supranational federal democracy throughout the world and constitute a model and a beacon on hope for the future of Europe and the world.

Finally, we would like to thank all the authors and the editor who conceived this book, under the direction of the European Observatory on Memories (EUROM) and the Jean Monnet House, with which the Federalist Movement and the Spinelli Institute will be honoured to continue collaborating on common European projects.

LUISA TRUMELLINI

Secretary General of the Union of European Federalists (UEF) and

Secretary of Movimento Federalista Europeo (MFE)

STEFANO CASTAGNOLI

President of the “Altiero Spinelli” Institute of Federalist Studies and MFE President

Presentation:

The elections to the European Parliament in the broader perspective of the history of democracy

share

We can place our current European supranational polity in a sequence of democratic milestones on our continent. For some, the roots of democracy are very old, going back to Athens in the 5th century BCE. For others, while acknowledging the continued inspiration that classical antiquity provided in the eras to follow, modern democracy is something fundamentally new that sets the enjoyment of individual rights as the core goal of society. Therefore, in its most fulfilled form, it does not condone the existence of disenfranchised people in its midst. In this sense, throughout the 19th century, democratic movements – and gradually, democratic regimes – were unable to establish themselves without espousing successive causes that would guarantee radical equality between individuals. These included the abolition of slavery, the passage from census suffrage to universal (male) suffrage and, in the 20th century, the hard-won right of women to vote. If we think that women did not have the right to vote in Switzerland until about 50 years ago, we realise how difficult it was to achieve equality on the European continent, and how fragile those accomplishments, on the whole, might still be. Similarly, if we think that, when Tocqueville extensively praised the US political system in La démocratie en Amérique, slavery still existed in the country and a civil war was about to be fought on this issue, we realise how flimsy some of our conventional democratic narratives may turn out to be.

Where does supranational democracy stand in all this? The coming of age of many democratic systems in European nation states in the second quarter of the 20th century was also the moment of democracy’s greatest challenge to date: the rise of authoritarianism and totalitarianism, in opposition to pluralism. In 1940, Altiero Spinelli and other prison inmates on the island of Ventotene reached a clear diagnosis when drafting the European Federalist Manifesto. They stated that the Second World War was raging at that very moment because of the inability of European nation states to combat totalitarianism3. At the same time, they saw totalitarianism as an intrinsic endgame to the ceaseless competition between nation states. As such, they predicted that, if victory over totalitarianism was to mean a return to the previous status quo, new competition between nation states would inevitably lead to totalitarianism again in the future. Whether or not one agrees with the Manifesto’s pessimistic vision of the ability of national constituencies to protect their own democratic life, regardless of the way the wind is blowing on the international stage, it is fair today to recognise the appeal of the Manifesto in calling for ideological and material resources to be pooled, to protect democracy through unity. Looking back, the Manifesto’s authors – like many other early proponents of a European democracy – reconnected with at least one of the main tenets of the first philosophical conceptualisations of modern democracy of the 17th and 18th centuries: the idea of a brotherhood of individuals across nations. From that point of view, the first concrete steps towards European integration in the mid-20th century can be understood as a fulfilment of early democratic ideas.

Some might question this last assertion on the grounds that the Schuman Declaration – the text Jean Monnet wrote and Robert Schuman endorsed, laying out those very first concrete steps – opened the door to technocracy, to solutions from above, or even, as Alan Milward argues, first and foremost to a rescuing of the nation state4. Underlying this idea is a myth that it is important to dispel. On the one hand, the beginnings of European integration drew on a staunch humanist tradition, espoused by, for example, Pierre Uri, one of Monnet’s closest collaborators, and Alexandre Marc, theorist of European federalism. On the other hand, since early on, Monnet had insisted on the need for a direct democratic vote to elect the European legislature. This view was shared by close allies, including a few other founding fathers: Paul-Henri Spaak and Alcide De Gasperi, who became Presidents of the Common Assembly, and Robert Schuman, first President of the European Parliamentary Assembly, later renamed the European Parliament. Even after Monnet relinquished the lead executive powers of the very first European community (the European Coal and Steel Community) when he stepped down as president of its High Authority in 1955, he continued to push for a directly elected European Parliament. This can be observed in the proceedings of many of the meetings of the Action Committee for the United States of Europe, the initiative to further European unity that Monnet was to steer for the next 20 years. Monnet concluded the work of the Action Committee in 1975, after the European Heads of State or Government at the Paris summit on 9 and 10 December 1974 declared that a direct election to the European Parliament ‘should be achieved as soon as possible’, and that they expected a direct election to ‘take place at any time in or after 1978’5. Nearing his nineties, Monnet was convinced that the announcement heralding a new generation of elected European representatives was the perfect time to retreat permanently to his home in Houjarray, France. He died just a few months before the 1979 election, and before two European founding mothers, Louise Weiss and Simone Veil, inaugurated the first ever directly elected European Parliament.

The publication you have in your hands reviews the nine elections that have taken place since 1979, as we look towards the 10th in 2024. This seems a fitting juncture for the historical and sometimes personal appraisals set out by the authors in the following pages. Together, they tell a story of excitement and shared ambition. That story also serves as a wake-up call for us not to take for granted the fruits of our common European democracy, and to stay committed to our European ideals through participation.

MARTÍ GRAU SEGÚ

Head of Service and Curator of the

Jean Monnet House of the European Parliament

Forewords

The Roots of European Elections

From the periphery to the centre of EU power:

the step-by-step rise of the European Parliament

share

by Richard Corbett6

Unlike most national parliaments, the European Parliament has never regarded itself as part of a settled constitutional system, but rather as part of one that was evolving and that required change. Hence, it sought not only to influence day-to-day policies, but also to change the basic framework of the Union. It repeatedly pressed the Member States to revise the treaties, which constitute the basic rulebook or de facto constitution of the Union. It also sought to interpret the treaties, stretching them like a piece of elastic, and to supplement them with interinstitutional agreements or by unilaterally introducing new practices.

When the European Community (now the European Union) was created, it was given powers to adopt binding legislation in a limited number of fields. But the power to adopt such legislation was given to the Council, composed of ministers representing national governments, acting on a proposal of the Commission, a collegial European executive appointed by national governments. The Council could approve Commission proposals in most matters through qualified majority voting (QMV), but unanimity was required to modify them. On some issues, unanimity was required to adopt a proposal. The European Parliament was merely asked for an opinion on some items of legislation, and it had no say at all on the appointment of the Commission.

So, when, in 1979, voters first elected the European Parliament, they were effectively asked to choose members of a debating forum, with no substantive powers on legislation. Parliament did have the right to dismiss the Commission in a vote of censure by a two-thirds majority, and to reject the budget – important but unwieldly powers that could scarcely be used on a day-to-day basis.

Many felt that such a system, whereby ministers alone could adopt legislation without requiring the approval of any parliament, suffered from a democratic deficit, a criticism not surprisingly shared by most of those elected to serve in the European Parliament. They became the vanguard for change.

Electing Parliament transformed it from the previous, somewhat sleepy assembly composed of members of national parliaments, who were able to devote only a small part of their time to it, into a livelier and more active Parliament. It effectively created a new corps of elected representatives, coming from every main political party in Europe and engaged full-time on European issues. They were not just active in Brussels and Strasbourg: they also brought a more informed debate on Europe into their respective national parties, influencing the debate back home, at least in political circles, and sometimes beyond. This helped shape the attitudes and positions of national parties and governments, not just on some specific issues, but also, to a degree, on the fundamentals of European integration. Over time, that helped encourage governments, including some previously reluctant ones, to be more amenable to a stronger European Parliament.

But Parliament’s route to power was nonetheless a hard-fought one. MEPs had to embark on a lengthy struggle, using a variety of tactics, from gentle persuasion to political conflict. They sought to interpret the treaties in creative ways, to supplement them with interinstitutional agreements, and to leverage the powers that they had to secure incremental concessions. They also proposed treaty changes.

Remarkably, over a period of four decades, Parliament became a genuine co-legislator in a European Union that had itself evolved considerably beyond the original European Communities, both in scope and in powers. Parliament and the Council now form a bicameral EU legislature. Parliament’s approval is required for:

-

- the adoption of almost all EU legislation,

- the approval of international agreements entered into by the EU,

- the adoption of the medium-term budget and the annual budget,

- the election of the President of the Commission,

- the appointment of the Commission as a whole,

- the conferral of delegated legislative powers on the Commission.

It also has a number of other powers, such as vetoing certain kinds of Commission decisions, electing an Ombudsman, and involvement in various other appointments (to the boards of agencies and to the European Central Bank).

There are still some gaps in what one might expect of a fully fledged parliament. There is still a category of special legislative procedures where the Council alone can adopt legislation. The dismissal by Parliament of the Commission in a vote of no confidence requires a two-thirds majority. Like the Council, Parliament can request the Commission to draft a proposal, but it itself has only a limited right to initiate legislative proposals. However, this is a traditional parliamentary power that most national parliaments rarely use, as legislative proposals in the modern era almost invariably come from the executive. Let us now look at how these changes came about.

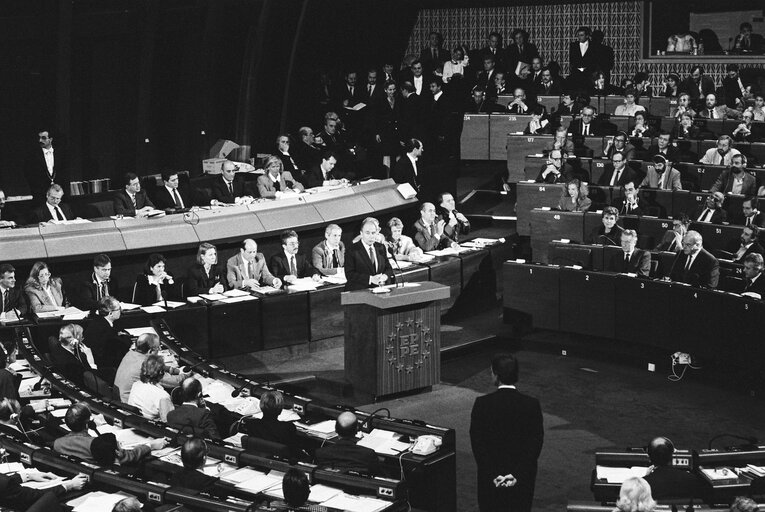

Enlarged Bureau meeting in Luxembourg, press conference – December 1985. From left to right, recognisable in the photo: Simone Veil, Nicolas Estgen, Giovanni Cervetti, Mario Didò, Pieter Dankert, Pierre Pflimlin, Maria Luisa Cassamagnago Cerretti, Giovanni Giavazzi, Hans Nord, Altiero Spinelli. | © Communautés Européennes – Source : PE

Treaty changes

The first elected European Parliament launched an ambitious initiative by putting forward a proposal to replace the European Community treaties with a new treaty on European union. Parliament took its lead from Altiero Spinelli, one of the founders of the federalist movement at the end of the Second World War, a former resistance leader and former member of the Commission who was elected to Parliament as an independent from a list put forward by the reformed Italian Communist Party. Spinelli hoped that a proposal agreed by a large majority of Europe’s political parties, as represented in Parliament, would carry weight and have momentum.

That strategy worked, to a degree. It did not result in Parliament’s draft treaty being ratified as such, nor even for negotiations to be based upon it (despite several national parliaments and governments calling for that), but it did lead to the convening of an intergovernmental conference (IGC), the procedure for revising the existing treaties. The European Council, meeting in June 1985 in Milan, decided by an unprecedented majority vote to convene an IGC, with the UK (Margaret Thatcher), Denmark and Greece voting against. The three recalcitrant Member States were eventually willing to negotiate compromises rather than be isolated.

The result fell well short of what Parliament had proposed in its draft treaty. But it did increase the areas of European responsibility, extend QMV and give Parliament some, albeit limited, legislative power for the first time, by creating two new procedures: the cooperation procedure and the consent procedure. The cooperation procedure made provision for a second reading in which Parliament could approve, amend or reject the Council’s position. A parliamentary rejection, or amendments that were also backed by the Commission, could only be overruled by the Council if unanimous, but that only applied to 10 articles of the treaty. The consent procedure (then called assent) meant that Parliament’s approval in a single yes/no vote was required for the accession of new Member States and for association agreements with non-EU countries.

This set of amendments and additions to the existing treaties was called the Single European Act (SEA). It introduced a deadline (end of 1992) for completing the single market, which gave a new sense of purpose to the EU and, in turn, generated new pressures for reform and further integration measures (such as a single currency for the single market). It was the first general revision of the treaties since 1957, breaking what had become a taboo and thereby paving the way for more revisions later.

Indeed, this pattern was to be repeated four more times: Parliament pushing for treaty reform, putting precise proposals on the table and helping secure an IGC, resulting in a partial but insufficient reform. This resulted in:

-

- the 1992 Treaty of Maastricht,

- the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam,

- the 2001 Treaty of Nice,

- the 2007 Treaty of Lisbon.

For each of these negotiations, Parliament was brought further into the treaty reform process. For the IGC that led to the SEA, Parliament’s President and Spinelli were politely heard at one of the meetings. For the Maastricht negotiations, an interinstitutional conference met in parallel to the IGC. For Amsterdam, Parliament had two representatives in the preparatory Reflection Group and participated in some of the IGC meetings, including the final European Council meeting. For Nice, the two Parliament representatives participated fully in all IGC meetings. For Lisbon, a preparatory convention (suggested by Parliament) composed of members of the European Parliament, national parliaments and national governments, prepared the reforms. These were codified in a new constitution which would have replaced the existing treaties, but which fell when France and the Netherlands rejected it. That led to a decision to keep the existing treaties but amend them through what became the Lisbon Treaty, which took up the bulk of the proposed reforms. The convention method is now laid down in the Lisbon Treaty for future revisions, except where Parliament agrees that it is not necessary.

Each one of these treaties extended the EU’s areas of competence, enlarged the area in which the Council can act by QMV, and extended the powers of Parliament. Each one was only a partial reform. But cumulatively, they transformed the European Community as it was before 1987 into the Union that we know today.

Parliament’s legislative powers were increased step by step. The SEA tentatively brought in the cooperation procedure. This was supplemented with the codecision procedure in the Maastricht Treaty, before being replaced by the codecision procedure in the Amsterdam Treaty. Codecision was itself revised in Parliament’s favour by the Amsterdam Treaty and extended in scope in the Amsterdam, Nice and Lisbon Treaties, until it became the ordinary legislative procedure, applicable to the bulk of EU legislation, and requiring the agreement of both Parliament and the Council for legislation to be adopted, with up to three readings in each institution. The consent procedure, initially envisaged only for the occasional cases of accession of new Member States and association agreements, was gradually extended to cover all significant international agreements and some specific types of legislation. Since Lisbon, any delegation of powers to the Commission to adopt delegated acts must be approved by Parliament and can be repealed by it, and Parliament also has the right to block individual delegated acts adopted by the Commission.

Similarly, Parliament’s relationship with the Commission was modified step by step. The Treaty of Maastricht changed the Commission’s term of office to five years to coincide with that of Parliament. A new Commission would be appointed straight after each parliamentary election, with Parliament consulted on the choice of President and holding a binding vote to approve or reject the Commission as a whole. Amsterdam changed the consultative vote on the President into a binding one and gave the President a right to choose other Commissioners jointly with national governments. Nice gave the President the power to appoint Vice-Presidents, and to dismiss individual Commissioners (for instance, if Parliament called for that). It also introduced QMV for the European Council’s decision on who to propose for President, eliminating national vetoes. Lisbon required the European Council to take into account the European election results when deciding who to propose to Parliament as President of the Commission. It described Parliament’s vote on the nominee as an election; it was not merely a seal of approval on a decision taken elsewhere, but the key point of the process.

These changes strengthened perceptions of the Commission as a political executive needing the support of a parliamentary majority. It might be a relatively weak executive, since it is faced with a bicameral legislature that it does not control through compliant majorities, has limited areas of responsibility, and inevitably is a coalition in party-political terms. However, it is undoubtedly an executive; it is charged with carrying out agreed policies, endowed with the right of legislative initiative, responsible for executing the budget, and it employs the bulk of EU civil servants. The fact that, from that point onwards, neither its President, nor the Commission as a whole, could take office without the approval of Parliament was seen as the democratic counterpart to this. And, since the choice of a new President would be one of the first things a newly elected Parliament would vote on, it became inevitable that the choice of President would feature among the issues of the European election campaign. This has resulted in European political parties nominating their preferred candidate ahead of the elections, much as national parties do for the position of Prime Minister in most European countries, ahead of national parliamentary elections. These party candidates are often referred to as their ‘lead candidate’ (Spitzenkandidat) as they also lead their party’s election campaign, not least in televised election debates.

First meeting of the Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community on 10 September 1952, chaired by Paul-Henri Spaak.

But not just treaty changes

These changes to the EU’s de facto constitution (the treaties) were not the only way in which Parliament enhanced its role. Indeed, sometimes treaty changes codified practices developed previously by other means.

On the legislative side, immediately after the first elections, Parliament was presented with an opportunity to strengthen its position within the treaties as they then stood. The 1980 isoglucose judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Communities (Cases 138 and 139/79) struck down legislation because the Council had adopted it before Parliament had given its opinion. This ruling confirmed that Parliament’s mastery of its own timetable (something that many national parliaments do not have) means that it has a de facto delaying power. It therefore changed its internal rules of procedure, so that it could prepare amendments to legislative proposals but delay the formal adoption of its opinion as a whole until it received assurances about whether its amendments would be approved. Clearly, Parliament’s bargaining position was stronger when there was pressure for a rapid decision than when there wasn’t, but it was a start. It helped to get the Council used to the need to negotiate with Parliament.

On the appointment of the Commission, Parliament unilaterally started holding debates and taking a vote on an incoming Commission, starting with the Thorn Commission in 1981. The Member States recognised and accepted this practice in their Solemn Declaration on European Union (at the European Council in Stuttgart in 1983), in which they also agreed to consult Parliament’s Bureau on the choice of Commission President. In 1985, the incoming Delors Commission waited for Parliament’s vote of confidence before taking the oath of office, an important symbolic gesture recognising the significance of Parliament’s vote on the Commission, and implying that, had the vote gone against it, it would not have proceeded. These practices paved the way for subsequent treaty changes.

Some innovations have not been codified in the treaties but have become accepted practice, even when initially resisted by other institutions. The most visible example of this is the public hearings of candidate Commissioners that Parliament organises ahead of its vote of confidence on an incoming Commission. Each candidate Commissioner is cross-examined by the parliamentary committee corresponding to their prospective portfolio. Parliament unilaterally made provision for this in its Rules of Procedure, invoked for the first time in 1994. Despite some initial reluctance, the proposed Commissioners agreed to participate in the exercise, not least because Parliament would otherwise have simply postponed its vote of confidence until they did. Although Parliament cannot vote on individual Commissioners, only on the Commission as a whole (the doctrine of collective confidence applies, as in most countries between a parliament and the executive), the hearings are not just a formality. Candidate Commissioners can fall by the wayside if they perform badly, or if the hearings draw attention to other problems, or if (following more recent changes) Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs finds a conflict of interest. This is especially the case if opposition to the candidate might endanger the vote on the Commission as a whole, as was dramatically illustrated in 2004. Then, criticism focused notably, but not exclusively, on Rocco Buttiglione, whose comments on the role of women and gay people caused many MEPs to question his ability to serve as Commissioner for Justice and Home Affairs, which included responsibility for non-discrimination. Initially, Commission President-designate Barroso appeared to want to brazen it out and count on a narrow victory in the vote of confidence, but when it became clear that he could lose, he instead announced in Parliament, just ahead of the vote, that he was withdrawing his team and would come back with a new proposal. He did so the following month with a new Italian nominee (Foreign Minister Franco Frattini), a new Latvian nominee, and a reshuffling of the Hungarian nominee to a new portfolio, thereby meeting Parliament’s main concerns. Strikingly, every prospective Commission since then (in 2009, 2014 and 2019) has seen at least one candidate Commissioner fall in this way

Parliament did not just act unilaterally. It negotiated interinstitutional agreements (IIAs) bilaterally with the Commission (the most important of which is the Framework Agreement) and trilaterally with the Council and the Commission (the most important of which is the IIA on Better Law-Making). These IIAs specify a number of obligations, for reporting to Parliament and giving it access to documents (including confidential ones). They also require legislative programming to be negotiated and agreed by the three institutions, and set out requirements for responding within a deadline to Parliament’s legislative initiatives, and for the President-designate of the Commission to present political guidelines for their term of office before they are elected by Parliament.

The elected parliament also made use of its (few) old powers that the previous unelected parliament had never used. It has rejected the annual budget outright on four occasions, temporarily freezing EU spending and putting extra pressure on the Council in a second budget procedure. It has deployed the power to dismiss the Commission. Parliament had enjoyed this power from the beginning but it seemed rather theoretical until early 1999 when it was spectacularly illustrated with the resignation of the Santer Commission, after it became clear that there was the necessary majority in Parliament for a vote of no confidence.

Conclusions

The successive treaty revisions since the European Parliament began to be directly elected were all strongly influenced by Parliament. They illustrate that, while Parliament, like other institutions, is not able to secure all its wishes, it can nonetheless have a major influence and is a catalyst for change. The changes made transformed the European system as a whole and especially Parliament’s place within it.

When Parliament proposed its draft treaty in 1984, the Community was in crisis, and confidence in its future was at an all-time low. Summits had broken down over the issue of the budgetary contributions of Member States, the European economy was in a period of Eurosclerosis and few thought that there was any realistic chance of amending the treaties. Yet, in thrashing out an agreement among the political forces represented in Parliament and pressing it on governments, through national parliaments and via national political parties, Parliament was able to create sufficient political momentum for at least some national governments to press its case, and for a majority of them to accept that there was a case to look at. Of course, the bottom line of unanimity among the Member States meant that there were limits as to what could be achieved, but the momentum was sufficient to enable a compromise package to get through.

This process was repeated several times. Certainly, the general political situation often improved the prospects for change. The SEA was also responding to economic stagnation and the persisting fragmentation of the European market. Maastricht became about more than the single currency, in part because of the dramatic changes in eastern Europe. Amsterdam and Nice were driven, in part, by the prospect of 10 new countries joining. But there is no doubt that the extension of Parliament’s powers would not have found its way into these processes, had it not been for Parliament’s constant pressure (and the same applies to new EU competences on citizenship, consumer protection, education and culture).

Taking these episodes together, their cumulative results are striking. In what is historically a short period of time, the European Parliament has come a long way. It sought and eventually obtained a power of codecision with the Council on legislation, so that the EU now has a bicameral legislature. It has acquired a central role in the appointment of the Commission and its President, to complement the right of censure that it had from the beginning. Its approval is needed for international agreements to be ratified by the Union. It now has an effective right of scrutiny and recall over delegated legislation. In short, the rise of Parliament is one of the most significant features of the five successive treaty revisions that took place between 1987 and 2009, and of the smaller adjustments and practices that developed during and since that time.

Having an active and assertive elected parliament with significant powers makes the EU radically different from a traditional intergovernmental organisation. To appreciate this, we need only imagine what the EU would be like without Parliament; it would be a system dominated by bureaucrats and diplomats, loosely supervised by ministers flying periodically into Brussels. Instead, the EU system is made more open, transparent and democratic than it would otherwise be, through the existence of a body of full-time representatives at the heart of EU decision-making, asking questions, knocking on doors, shining a spotlight into dark corners, in dialogue with voters back home, and whose approval is necessary for key decisions. MEPs are drawn from governing parties and opposition parties and represent not just capital cities but the regions in their full diversity. In short, Parliament brings pluralism into play and brings far more scrutiny to EU legislation.

It also takes the edge off national conflict. All too often, the Council can give the appearance of decision-making by gladiatorial combat between those representing ‘national interests’. Reality is more complex, and the fact that Parliament organises itself, not in national delegations but in political groups, shows that the dividing line on most concrete subjects is not so much between nations but between different political viewpoints or between various sectoral interests.

Simone Veil and the first European universal suffrage

share

by Nadine Vasseur 7

The European Parliament’s first elections by universal suffrage in 1979 marked the beginning of a new chapter in Europe’s history. The election of Simone Veil as the first European Parliament President on 17 July 1979 was one of the most powerfully symbolic moments of this new period.

French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing grasped the significance of her election from very early on. As Simone Veil put it, ‘Giscard has always loved symbols that capture people’s imagination. For a former deportee to become the first President of the new European Parliament seemed to him to augur well for the future’8.

Simone Veil was a Jewish woman who survived Auschwitz. Most of her family was exterminated by the Nazis. Following her entry into the government in 1974, she became the most popular political figure in France and was also admired beyond the country’s borders. Veil was both the embodiment of the worst suffering that Europe’s 20th century wars could have inflicted and the personification of resilience. It is impossible to imagine a more powerful symbol of Franco-German reconciliation than her election as President of the European Parliament.

In September 1978, Giscard asked Veil, who was still his Minister of Health, to head the list of the party in government (the Union for French Democracy) for the European elections.

When Veil was put forward as a candidate, she had never been registered with a political party, had never been elected into office and had never taken part in an election campaign. She hated the heated atmosphere of the meetings, was uncomfortable with the political clichés and was certainly not the greatest speaker there. None of this kept her from defending herself brilliantly when she felt attacked. All French people who were alive at the time remember the images from the meeting she attended on 7 June 1979, violently interrupted by far-right National Front militants, and Veil’s cutting retort which would go down in history: ‘You don’t scare me at all! I’ve survived worse than you. You’re just the SS in miniature.’

In addition to her immense popularity as the Minister of Health and as a media personality, her unrehearsed style on the campaign trail was her real strength. Simone Veil spoke like everyone else, avoiding political jargon. She was outspoken and thought freely, which allowed her to reach even those who were not of her political persuasion.

Her list, which gained 27.5 % of the vote, won by a large margin, coming ten points ahead of the Gaullist list headed by Jacques Chirac. ‘Indeed’, Simone Veil noted, with her characteristic astuteness, ‘standing for a parliament whose very existence they contested looked like a paradox, as the public was not slow to observe’9.

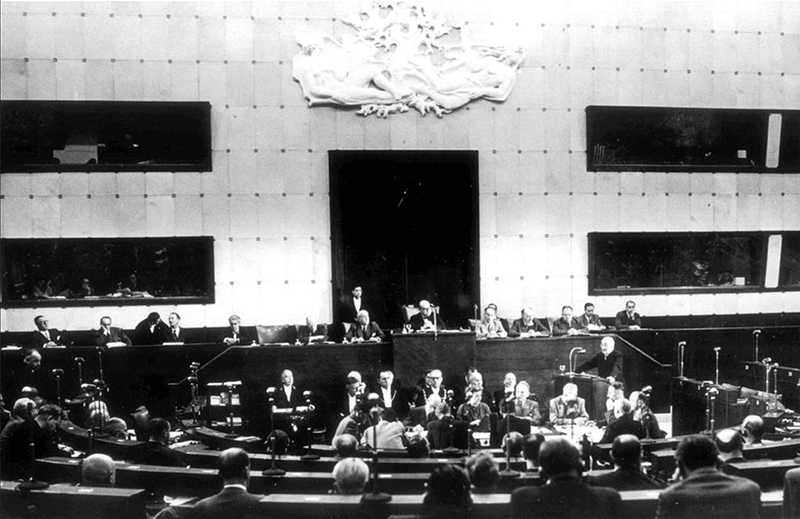

Simone Veil, newly elected President of the European Parliament, during the first session of the first directly-elected European Parliament Event date: 17 July, 1979 | © Communautés européennes 1979

Unlike President Giscard d’Estaing, who had always been committed to holding European Parliament elections by universal suffrage, the Gaullists were actually strongly opposed to the elections. Following in the footsteps of General de Gaulle and President Georges Pompidou, they saw it as a first step on the road to abandoning national sovereignty. This lack of agreement on Europe was one of the issues that would always distance Simone Veil from de Gaulle and Gaullism, despite her lifelong friendship with Jacques Chirac.

Following the Union for French Democracy’s victory, Giscard worked tirelessly to promote Simone Veil’s election as European Parliament President, with the discreet support of Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. She secured a majority in the third round of voting.

For Simone Veil, being elected President of the European Parliament was the culmination of a lifelong struggle.

The day after Veil’s death, Sylvie Kaufmann wrote that she was part of ‘this impressive Franco-German generation who dared to build the Europe of hope on the still smoking ruins of the Second World War’10, at the same time recalling the life’s journey of Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who had passed away several days earlier, and who had also been a great architect of Europe.

As Simone Veil pointed out during the 1979 European election campaign, ‘of the peoples of Europe, the most European are those who have endured the greatest suffering’11. She was certainly thinking of the Jews who survived the Holocaust but also undoubtedly of the German members of her audience who, early in their lives, had experienced the loss of close relatives at the same time as that of their country’s honour.

In her inaugural speech on 17 July 1979, she did not forget the Spanish, the Portuguese or the Greeks, recently liberated from dictatorships, stating that ‘the Community will be happy to receive them’. A fervent advocate of European enlargement, she would not fail to think later, after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, of the peoples of eastern Europe. She felt that those living in western Europe, who had been ‘lucky … to live in a free system … when the Iron Curtain closed off the other half of Europe’ had taken on a kind of debt towards those in the East. ‘When history gave us the opportunity, it would have been unthinkable for the EU not to open its doors to these countries … even at the expense of our immediate economic interests.’12

European election in France – June 1984 | © European Union 1984 – EP

This ‘European adventure was and remains the great challenge faced by my generation,’ she would say in her twilight years, during her 2010 acceptance speech to the Académie française.

While Simone Veil’s journey is similar to that of many of the great pro-European figures of the post-war era, it is nevertheless distinguished by one unique trait: its European fibre is part of a story which goes back to well before the post-war period. In her memoir, one is struck by the precision with which she recalled conversations she had heard between her mother and father, when she was just a child and the dangers Europe and her loved ones were facing were coming into focus.

On the one hand, there was her father, who had been taken prisoner by the Germans during the First World War, and whose hatred for the people he only ever referred to as the ‘Boches’ never diminished. On the other hand, there was her mother, who, faced with the burgeoning Nazi threat, bitterly regretted that the Franco-German rapprochement advocated by Aristide Briand and Gustav Stresemann had never materialised. It could have prevented Hitler’s rise to power.

Simone Veil never forgot her mother’s words. Even after being deported, she remembers that she did not stop thinking about the lessons of the past: ‘I didn’t understand how we hadn’t learned from the horrors of 1914 to 1918’13. ‘At the camp, when I imagined returning home – which was not something I did often – I wondered how we would manage with the Germans … I thought that if we couldn’t find a way to reconcile, our children would also become caught up in this hatred.’14

Later, when her husband Antoine Veil was appointed to a post in Germany in the early 1950s, she did not hesitate to follow him, to the utter amazement of many of her relatives. Simone Veil often expressed her lack of a desire for revenge. She never let emotions cloud her view that the reconciliation between France and Germany was crucial. It was based on a rational vision: to preserve peace in Europe for future generations.

The Europe she was promoting was above all geopolitical and cultural in nature. It was the Europe of peace after centuries of fratricidal conflicts, of democratic freedoms in the face of totalitarianism. It was also the Europe of solidarity.

For Simone Veil, justice was important. She had a social conscience, which sometimes made it difficult to position her on the political spectrum, and which often aroused the sympathy of voters and figures with socialist tendencies. This can be seen, for example, in the warm tribute paid to her following her death by former President of the European Commission and left-wing French political figure Jacques Delors, who also passed away recently. ‘Simone Veil and I were elected together in 1979. We were not elected on the same lists, but we shared a lot of beliefs about Europe. In her inaugural speech, she also talked about a Europe of solidarity, a Europe of independence and a Europe of cooperation.’15

European election of June 1984 in France | © European Union 1984 – EP

At the beginning of her term of office, back when the European Parliament’s powers were still limited to approving the Community budget, Simone Veil went against her own government’s position and managed to secure financial aid to combat hunger in Africa. Issues of human rights and women’s rights would be at the heart of many of her journeys around the world.

It was not only Veil’s renown but also her aura that enabled her to make the European Parliament shine at a time when it still seemed lacklustre and niche. She played a major role in giving the European Parliament its fully international dimension. Simone Veil proudly upheld the values of a democratic Europe wherever she went. First as European Parliament President, then for over ten years as an MEP, she met most of the great heads of state, including Anwar Sadat, Nelson Mandela, Margaret Thatcher, Bill and Hillary Clinton and Václav Havel.

In a 2010 interview, Jacques Delors praised another ‘rare quality’ Simone Veil demonstrated during her time as European Parliament President: ‘discernment’16.

It is impossible to read Simone Veil’s biography without being struck by her clear-sightedness. She did not delude herself and was not afraid to look danger in the eye. As a child during the war, despite being the youngest member of her family, she was already the most realistic about the grim fate that awaited them all.

Her unwavering commitment to Europe never blinded her to the threats that could jeopardise its future: in particular, the threat that national interests could prevail over those of the Community. This risk became all the more serious as Europe expanded, making it increasingly difficult to achieve unanimity, or even a majority, in matters of governance. Long before being elected to the European Parliament, Simone Veil had, like others, imagined a federal Europe; an outlook which, as far back as 1979, was no longer shared by the younger generations, who had a greater desire to ‘go back to the roots’17. An aspiration which would, in her view, grow ever stronger: ‘I can’t help but notice the citizens’ growing attachment to their national frameworks and to the historical factors that have shaped unique identities’18, she remarked, not entirely unconcerned, after the 2005 vote to ratify the draft Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe, which resulted in a ‘No’ vote in the referendums held in France and the Netherlands.

Simone Veil’s time as an MEP ended in 1993. In 1998, the French Government appointed her to the Constitutional Council, where she served until 2005. That year, she went against her duty to remain politically neutral and strongly committed herself to the ‘Yes’ side in the referendum, because ‘a Europe built patiently for decades can crumble tomorrow. What some have tirelessly built, others can destroy.’

The 2005 referendum would be her last public political commitment.

Simone Veil said on numerous occasions that, ‘The fact that we have built Europe has reconciled me with the 20th century.’

At the dawn of the 21st century, she was determined to warn people about the fragility of this common good. She believed that it was essential to remind younger generations, who had not experienced war, that this ‘miracle of peace’, which seemed natural to them, was the fruit of the relentless determination of men and women who had wished to leave them a Europe which was no longer a place of destruction. She asked them to take good care of it.

Louise Weiss, a campaigner for Europe

share

by Christine Manigand 19

On 17 July 1979, Louise Weiss, as the oldest Member, stood at the rostrum of the European Parliament in Strasbourg to address her fellow Members after they had been elected by direct universal suffrage for the first time. She spoke of the pride and joy that she felt, at the age of 86, on taking her seat in the chamber and presiding over Parliament’s inaugural session. The ‘President for a Day’, as she called herself in a memorable speech20 entitled ‘A fight for Europe’, expressed to her colleagues ‘the greatest joy a human being can experience in their autumn years, the joy of a youthful vocation miraculously achieved’. The following day, in the same debating chamber, she handed over to Simone Veil, who had been elected President of the European Parliament.

During her speech, Louise Weiss described herself as ‘someone in love with Europe’, and it is the journey of this committed woman, a campaigner for Europe, which we would like to retrace, from the battles she fought as a young woman in the interwar years to the final speeches she made to the European Parliament elected in 1979. Louise Weiss left us a series of six books recounting her life entitled Mémoirs d’une Européenne (Memoirs of a European). The title shows that Europe dominated her life, which spanned almost a century, from 1893 to 1983.

An emblematic European figure

In many respects, her childhood was European21, and she was raised between the Protestant and Jewish minorities, which strongly supported the republican model. Louise Weiss was born in Arras in 1893, into a Dreyfusard, upper-bourgeois family, and her Alsatian and Protestant roots came from her father, Paul Weiss. He was a graduate of the École Polytechnique and the École des Mines, Paris, and he left his position in the Ministry of Public Works for the private sector, where he felt more useful. Louise Weiss’ mother Jeanne Javal was from a wealthy Jewish bourgeois family with relatives in Alsace, Germany and Austria. At a very young age, when her father took her on visits, or almost pilgrimages, to Alsace, she came to understand the resentment that existed between France and Germany.

At the age of 21, and without daring to tell her father, she passed the agrégation teacher training examination in arts subjects, an extremely rare accomplishment for a woman at that time.

During World War I, she served as a nurse in a military hospital in western France and saw her brothers and her parents painfully separated on either side of the River Rhine. It was also during the First World War conflict that she wrote her first articles under a pseudonym and, at a salon in Paris, met Milan Štefánik, a Slovak astronomer serving in the French army as a pilot. This first ill-fated love story had a major impact on her campaigning, prompting her to espouse the cause of Milan Štefánik and Edvard Beneš, the leader of Czech emigrants in Paris: she instantly embraced their aspirations for a future independent Czechoslovakia that would be free from the yoke of the Austro-Hungarian empire. For a time, her imagination was captured by the ‘beacon in the East’, which was developing in Russia and which she explored in her first pieces for a leading daily newspaper of the period, Le Petit Parisien. Weiss’ 1921 report, ‘Cinq semaines à Moscou’ (Five weeks in Moscow), earned her the beginnings of international renown.

She continued her journalism work in an international news weekly, L’Europe Nouvelle22, of which she was not the founder but became the director in 1923, after the editor-in-chief died. The date is symbolic because, at that time, Europe was contending with the issue of reparations and the Ruhr crisis.

One of Louise Weiss’ strengths was her ability to build around herself a network of permanent and temporary contributors, unofficial journalists and occasional columnists, as well as prominent statesmen and diplomats from all over Europe. Her close circle consisted of distinguished academics such as Louis Joxe, a young history professor; René Massigli, a young diplomat; Georges Bonnet, who would later become France’s Minister for Foreign Affairs; Wladimir d’Ormesson; and a multitude of French and European politicians, including Aristide Briand, to whom Louise Weiss was very close, Edouard Herriot, Léon Blum, Paul Valéry, Drieu La Rochelle and Jacques Benoist-Méchin. The foreign names were equally illustrious and revealed a whole network of European elites who embraced the ideals of pacifism based on the new concepts of collective security.

Louise Weiss gave her journal a distinctive style based on the seriousness and quality of her sources; the aim was to make it an instrument of well-reasoned information on international affairs serving the cause of a true science of peace. Significant column space was dedicated to the economic, financial and trade issues of the time. The weekly publication very quickly became the almost Official Journal of the League of Nations, as it published documents produced by the Geneva-based organisation in full. Apart from the arts and literary section, most of the articles focused on international affairs, the work of the League of Nations23, and the economic and political situation in various European countries, because, as the editor-in-chief wrote, ‘it is through in-depth knowledge of the elements that make up Europe that the workers of the European Federation will be able to work effectively’24. The aim of L’Europe Nouvelle was to explain the increasing complexity of international politics, and also to encourage the formation of new competent elites, with expertise in tackling international issues.

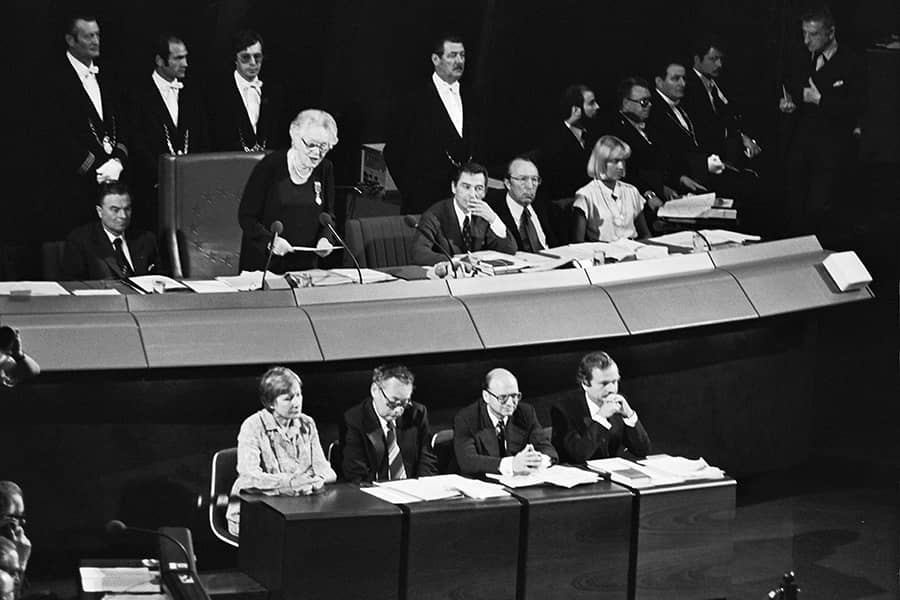

Louise Weiss chairs the Plenary as the most senior Member during the election of Simone Veil, 17 july 1979 | © European Parliament

Louise Weiss was committed to the reconstruction of Europe, the League of Nations and projects to build European unity as part of a multi-scale approach that combined universalist and regional views and, very often, coincided with the stances taken by Aristide Briand, the ‘eternal’ Minister, who served as the French Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1925 to 1932.

It was really from 1924 onwards that Weiss, in her role as editor-in-chief of L’Europe Nouvelle, became a champion of the League of Nations and involved in the mystique of the Geneva organisation; when she arrived in Geneva in September 1924 she was captivated by the atmosphere that pervaded the banks of Lake Geneva. From that moment on, the magazine began to dedicate substantial space to the debates taking place in Geneva and to the prominent figures that took part in them, and provided its readers with first-hand sources and documents in full. In the wake of the failure of the 1924 Geneva Protocol, which was based on the three pillars of ‘arbitration, security and disarmament’ and had been rejected by Great Britain, Louise Weiss placed her hope in Aristide Briand and his policy of détente; whether she influenced him or the magazine was a sounding box for Briand’s ideas, there was, in any case, a complete affinity between the two figures25.

Starting with the Locarno Conference in 1925, Louise Weiss decided to take part in all major international conferences and welcomed Germany’s entry into the League of Nations in 1926. In 1928, the agreement to renounce war, known as the Kellogg-Briand Pact, cemented her disappointment and made it clear that it would be impossible to bring the United States back into an important role in European affairs.

She therefore supported Aristide Briand’s proposal to establish a European federation in his speech before the League of Nations26 in September 1929. L’Europe Nouvelle served as a testing ground for this revolutionary proposal and, as early as July 1929, it published an article entitled ‘Towards a European Federation’ and, after September 1929, it became the most effective sounding board for Briand’s plan. There was a clear link between the topics that were being supported in the political and economic fields and their purpose: ‘The clear-sighted and profound mind of Aristide Briand does not make him a visionary spirit; he is a realistic spirit … he does not know, and nor do any of us know, what form an organised Europe will take and what destiny will await it. He only knows that Europe must be collective, that it is necessary, that it is called for and that it is immediately reflected in the unanimous support of the other countries of Europe … what must be understood is that it is a matter of European peace, much more so than of the United States of Europe’27. While the expectations of both were quickly dispelled, support for the League of Nations continued, but it too began to give way to disillusionment. Her final editorial (3 February 1934), when her struggle was inextricably linked to the aims of her journal, revealed an insightful European who perceived the dangers of the Nazis’ exploitation of pacifist topics from 1934 onwards. In 1936, for the same reasons, she suspended the activities of the Nouvelle École de la Paix (New Peace School, NEP), which she had established in 1931 to disseminate her ideals. Throughout the years, she had been driven by an unwavering commitment with three dimensions: the goal of bringing international cooperation into the mainstream and organising peace, a dedication to actively promoting Geneva’s ideals and a pro-European commitment.

While she bid farewell to L’Europe Nouvelle in February 1934, she became involved in a related endeavour. As a committed feminist, she founded the magazine La Femme nouvelle and organised suffragette demonstrations to call for women’s right to vote and equal civil and political rights. She symbolically ran in a number of elections, even though women did not have the right to vote. Once again, her commitment to peace, through women, was one of her key purposes.

During the war, given her Jewish origins on her mother’s side, she was obliged to be cautious and did not take part in the clandestine activities of the Resistance, instead limiting herself to resistance through the written word. It was perhaps for this reason that, after the Second World War, neither General de Gaulle, who gave women the right to vote, nor Jean Monnet offered her a fitting political role; she then decided to travel the world and directed ethnographic films and documentaries while establishing herself as a renowned speaker and writer.

Louise Weiss greeting Simone Veil upon her election as President of the European Parliament, July 1979 | © European Parliament

Return to Europe

In the 1970s, Louise Weiss returned to the European stage, firstly with her book Mémoires d’une Européenne, made up of six volumes, which were published in the 1960s by Payot and then completed by Albin Michel in the 1970s. In a very real sense, Europe dominated her life for almost an entire century.

In 1978, she was awarded the Robert Schuman Prize. Then, in 1979, after a lengthy process, the first elections of the European Parliament by universal suffrage were held. Louise Weiss took part in the French election campaign.

She was the fifth candidate on the Defence of France’s interests in Europe (DIFE) list, which was led by Jacques Chirac, and during the campaign she refused to challenge Simone Veil, who headed the competing list of President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s UDF party.

However, the competitive tension between the names on both lists was evident. After Jacques Chirac made his ‘appeal to the French people’ at Cochin Hospital on 6 December 1978, the position of the Rally for the Republic (RPR) party became increasingly anti-Europe, and ‘the list essentially brought together Gaullists known for their anti-European views – with the notable exception of Louise Weiss – and most of whom were national and local elected representatives’28. That list contained fewer women than the other four major lists (12 women out of 81 candidates). Is it therefore possible to speak of a ‘Louise Weiss smokescreen’29? Jacques Chirac had, indeed, promised her, that she would ‘be our First Lady’! The complexity of this situation was reflected in the few statements that Louise Weiss made during the election campaign.

One year later, these first elections would be considered second-order elections,30 that is, unusual elections with minor effects, no real issues at stake and a strong national focus, as well as very high abstention rates and a general lack of a European dimension. Nevertheless, the debate was at its fiercest and most intense in France. There were clear lines of opposition between the many political lists, which either took a pro- or anti-Europe stance. In a statement to Le Monde, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing explained that those elections were to be an opportunity to decide how France would be represented externally and not how it would be divided internally31. The European dimension of the elections was less diluted in 1979 than in later years because of the views of two parties, the RPR and the French Communist Party (PCF), who challenged the very legitimacy of the vote. Europe was evidently not a central concern for French people, since ‘only 25 % of respondents declared that they had voted according to the decisions taken by the parties on the construction of Europe, while 59 % stated that they had voted according to the challenges that France faced in economic and social policy matters’32.

Louise Weiss at the headquarters of “L’Europe nouvelle” | Source: Fondation Jean Monnet pour l’Europe

Indeed, while an overwhelming majority of French people approved of European integration, it actually seemed more like formal support than unreserved commitment, since only 35 % said that they would be willing to make personal sacrifices in order to achieve this European goal, compared to 60 % who would refuse to make such sacrifices33. A slight decline in the percentage of French people who were in favour of European unification was also recorded: it decreased from 61 % in autumn 1973 to 59 % in autumn 1978, and dropped further to 56 % in spring 197934.

The election of France’s 81 representatives to the European Parliament on 10 June 1979 did not spark much discussion despite the elections being widely acknowledged as important. Although they showed little interest in the European elections, French people did consider them to be important, but more because of the impact they would have on French politics than because of their importance for Europe as a whole. Throughout the campaign, national political issues therefore dominated and a major source of disappointment was the low turnout. In France, voter abstention reached an almost record high (38.8 %), with particularly high levels among young people (36 % of 28 to 34 year olds said that they had abstained) and manual workers (30 % intentionally abstained from voting)35.

The list led by Jacques Chirac received only 16.09 % of the votes cast, while the list headed by Simone Veil won 27.39 % of votes36. She led the list of France’s then-governing party, which fared better than the RPR, whose results made it one of Gaullism’s poorest performances. However, in France, as was the case in the United Kingdom and Denmark, there was no shortage of debate due to the strong opposition (of the Communist Party and the RPR) to direct elections and the construction of a political Europe.

Louise Weiss then took her seat in Strasbourg in the group of European Progressive Democrats (DEP) and on 17 July 1979, the date of Parliament’s opening sitting, she was one of 67 women Members elected, some of whom had already been Members of the European Parliamentary Assembly. Following the first direct elections, 16.3 % of the European Parliament’s Members were women, nine of whom were already sitting Members and were given a direct mandate from voters37. Louise Weiss, as has been described, was President of the European Parliament for one day, 17 July 1979, during which she handed over the Presidency to Simone Veil, who served as President until 18 January 1982.

During her term as a Member of the European Parliament, her main addresses focused on the Soviet Union’s intervention in Afghanistan, world hunger, human rights violations and Strasbourg’s European vocation.

She was a member of the Committee on Youth, Culture, Education, the Media and Sport. Its main aim was to give the European Community a museum of the history of European unification. To that end, she authored a report on ‘on the contribution of the Community to the development of Europe prior to establishing a museum of the history of European unification’. Louise Weiss was unable to finish her term, as she passed away in 1983.

In 1996, a museum was dedicated to her at Rohan Castle, in Saverne, France. Then, in 1999, the main building that houses the European Parliament’s debating chamber in Strasbourg was named the Louise Weiss building.

Louise Weiss, who Helmut Schmidt called ‘the grandmother of Europe’ in 1983, was one of those (rare) women who is always mentioned, but is not widely known as having been a campaigner for Europe. Although she may not have been included in the pantheon of the architects of Europe in the post-1945 period, the role she played went far beyond that of a pioneer of Europe. In the interwar years, she used her networks to promote the issues of Franco-German reconciliation, peace, international arbitration and the need for European unification. All the debates and challenges arising from the European project were considered, addressed and discussed after the Second World War. The influence she had, therefore, came from herself, from her philosophy of being committed to a cause with a determination that never wavered throughout the campaigns she fought as a European feminist in the 20th Century, and from a certain coherence between her ideas and actions.

The Roots of European

Elections

The 9+1 EP Elections

The besieged citadel of European democracy.

From the first European elections in 1979 to the 1984 Spinelli project

share

by Pier Virgilio Dastoli 38

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) distinguished itself from other international organisations with a regional dimension (including the Consultative Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) in many ways. Firstly, the ECSC’s sectoral competences had a supranational dimension; secondly, it gave a pre-eminent role to what was called the High Authority; and, thirdly, it created a parliamentary institution, namely the Assembly. The Assembly consisted of ‘delegates whom the Parliaments are called upon to appoint from among themselves once a year or elected by universal and direct suffrage in accordance with the procedure laid down by each High Contracting Party’ (Article 21, Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community).

Three characteristics of this Assembly defined its supranational dimension:

-

- its name (Europäisches Parlament in German, Europees Parlement in Dutch) evoked a relationship with the democratic legitimacy of national parliamentary assemblies;

- its composition, made up of European political families (Christian Democrat, liberal and socialist) and not of national delegations, thus evoking the transnational foundation of 19th-century political cultures, conceived from Christian universalism, liberal cosmopolitanism and socialist internationalism;

- the mandate given to it by the foreign ministers of the six founding members to draw up the statute, i.e. the constitution, of the European Political Community, as the political and democratic framework necessary for the birth of the European Defence Community.

After the birth of the European Communities through the 1957 Treaties of Rome, the assemblies of the ECSC, the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) were merged. This enlarged Assembly met for the first time in Strasbourg on 19 March 1958 and decided, on 30 March 1962, to take on the name of European Parliament – as Fernand Dehousse put it, ‘destined to one day become a real Parliament’.

The Treaties stipulated that ‘the Assembly shall draw up drafts for the purpose of permitting election by universal and direct suffrage in accordance with a uniform procedure in all member states’ (Article 2 of the Convention on certain institutions common to the European Communities and Article 138 of the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community). Relying on the power conferred on it by the Treaties, the European Parliament fulfilled its mission as early as 17 May 1960 and after two years of preparatory work, by approving a draft convention for the direct election of its members.

The Council did not implement the convention or the other proposals that the Assembly subsequently voted on because, for a long time, the governments and the prevailing doctrine supported the grotesque idea that a parliament without powers could not be elected by universal suffrage. At the same time, they supported the idea that no powers could be given to a parliament that was not representative of the vote of the citizens.

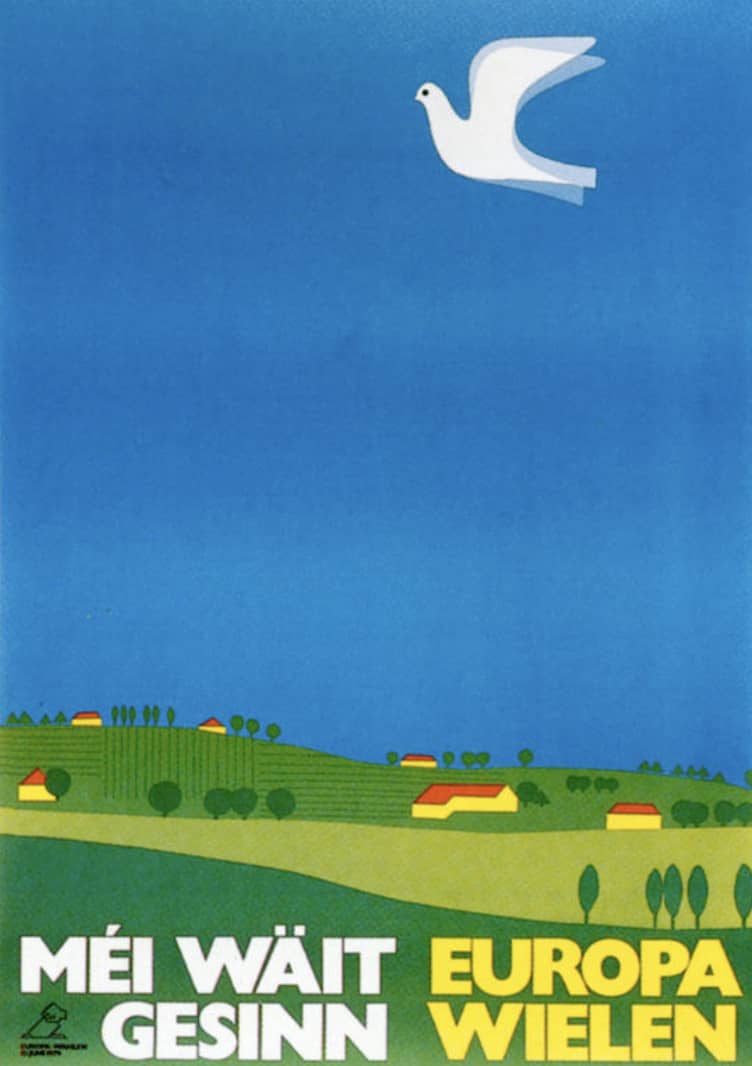

Luxembourg campaign poster for the first elections to the European Parliamentby direct universal suffrage, held on 10 June 1979. | © Europa Grafica – Commission européenne Répresentation au Luxembourg

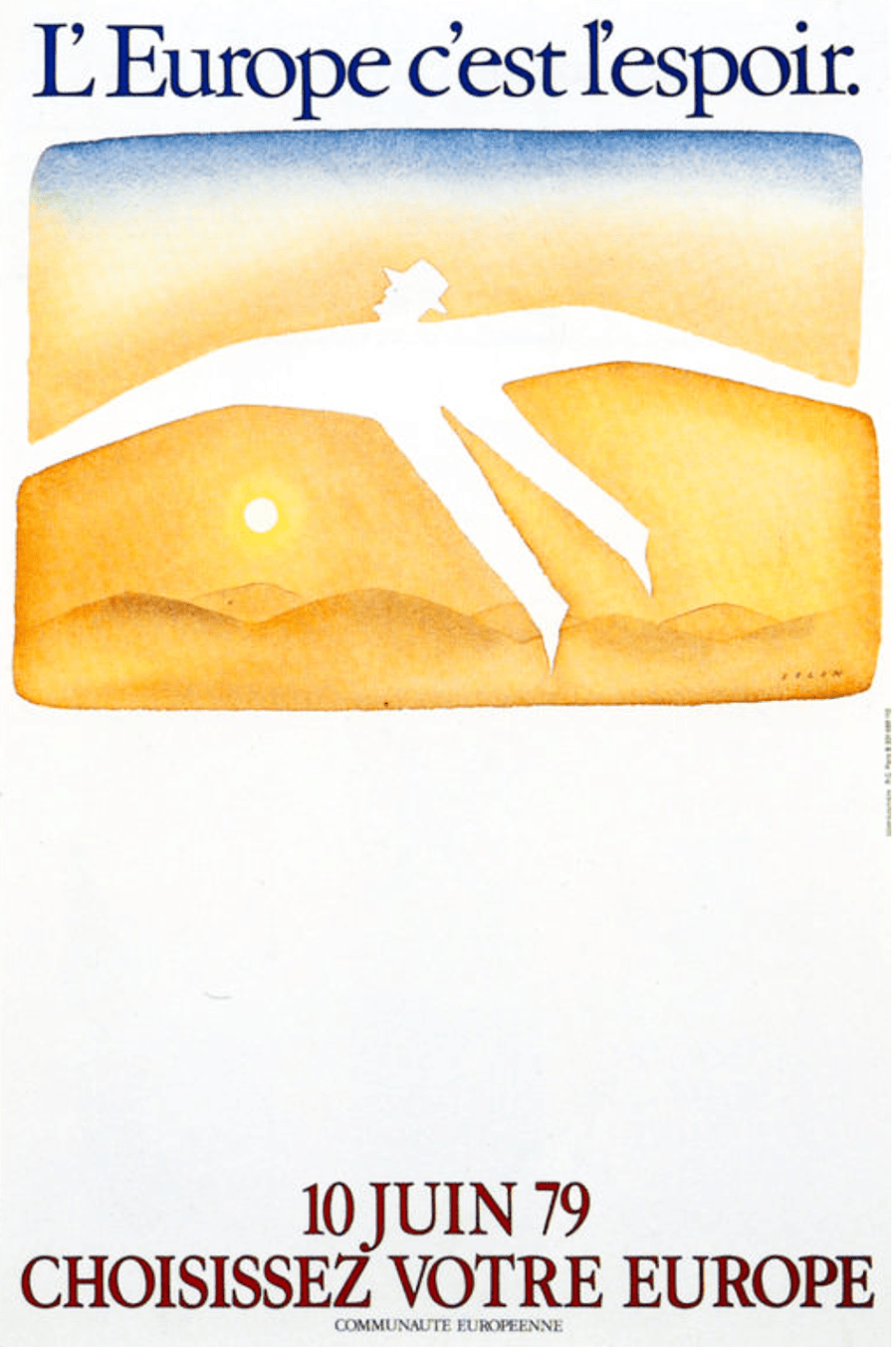

French poster designed by Belgian artist Jean-Michel Folon for the campaign preceding the first elections to the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage | © Communauté européenne

Despite the fact that it was not elected by universal and direct suffrage, and despite the letter of the Treaties, the European Parliament gradually gained some supranational powers in budgetary matters. In 1970, it was given the power to reject the draft budget prepared by the governments based on the proposal from the Commission. In 1975, it exercised this power again, following the Council’s recommendation to use a value added tax to finance the European budget. Parliament also gained the power to table amendments on so-called non-compulsory expenditure (i.e. all except agricultural expenditure), based on the principle of ‘no taxation without representation’.

As a logical accompaniment to the new budgetary powers, a conciliation procedure was introduced, i.e. an embryonic codecision procedure or legislative dialogue concerning ‘acts of general scope with important financial implications’, that later formed the basis of the trilogue process between the Commission, the Council and Parliament.

These steps forward had two effects, offering institutional potentials that were realised in the first legislative term of the Parliament elected in June 1979.

The first potential concerns regional policy, which, since the 1970s, had progressively become an essential part of the European budget, and , within the framework of economic, social and territorial cohesion, now exceeded expenditure on the agricultural price support policy.