“A refugee is any person who believes themselves to be persecuted in their country of origin for political, racial or religious reasons”.

Robert Schuman, French Secretary of State for Refugees: Quotation adopted by the Office Française de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (Papiers Cabinet Schuman 1946-1953, AMAE Paris)

I noted down this quotation some years ago, when I was consulting documents in the Cabinet Robert Schuman at the French foreign ministry at the Quai d’Orsay where Schuman was an outstanding diplomat and minister. Defining and commemorating Robert Schuman’s legacy is a complex but necessary task. At the European Observatory of Memories, we are celebrating it as a way of defending the idea of Europe: a Europe full of challenges and crises, but also of hope and opportunities, which should never forget the collective or individual processes that have shaped our free societies, our memory, and the democratic values of peace and social justice.

Solidarity, human rights and fraternal federalism between the peoples of post-world war Europe: these ideas, among many others, were given voice by Robert Schuman, French foreign minister and one of the fathers of today’s European Union. His efforts were not always appreciated, nor were they without their contradictions (for instance, Schuman negotiated the reopening of the French border with the repressive dictatorship of General Franco with “discretion and neutrality”).

The project of the unprecedented “union” required the de facto creation or reconstruction of democracies, but for Schuman, above all, it meant the acceptance and recognition of West Germany inside a new Europe, based on the granting of sovereignty in favour of an idea of a federation of peoples and societies and, initially, economies on a multinational scale. But Schuman was determined to create a strong united group of European countries to reinforce these values of solidarity, in combination with an economy of reconstruction brought into being by the Marshall Plan, and in opposition to the Soviet bloc that emerged in the early days of the Cold War. Europe was gradually rebuilding; France had drawn closer to Germany, which was no longer an enemy but an ally in a group of emerging partners led by France and Britain. It was a western Europe full of refugees that had to be united to face the uncertainties of the new Cold War and ideological confrontation.

Robert Schuman made the project his own. The diversity of its peoples, migrants and societies was the guarantor of European wealth, and it was vital that it should remain so. The instigators of the new Europe took the economy as its starting-point; but thanks to the single-mindedness of Schuman and his many allies among politicians and diplomats the current European Union was created. Many of the political, cultural, and social challenges noted by Schuman persist in our Europe, stronger and broader now than ever before, but put to the test every day. Schuman knew that this would be so. His efforts and lessons should be remembered and taken into consideration for the sake of our present, our memory of solidarity, our future, and our most precious assets: peace, social progress, and democratic justice.

JORDI GUIXÉ

Director of the EUROM

The Schuman Plan:

some reflections, 70 years on

share

Sylvain Schirmann

Lecturer in contemporary history

The Jean Monnet Chair

Political Sciences, Strasbourg

The Schuman Declaration was not the first governmental project designed with the aim of building a united Europe. When the French Foreign Minister presented the core of the plan that bears his name on 9 May, 1950, it had a number of precedents (one of them the Briand Plan of 1929), and in fact the construction of Europe and cooperation between European states was already underway. As early as 1948, with the creation of the Western Union and the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC), the states of Western Europe had frequently discussed their economic reconstruction and had coordinated their policies in this area within the framework of the Marshall Plan. A more restricted circle comprising the Benelux countries, the United Kingdom and France also organized strategic discussions and sought new forms of political cooperation. The Congress of the Hague, held in the same year of 1948, cherished the hope of establishing a political Europe through institutions that would reunite the European family. The opposition between the supporters of an intergovernmental Europe and those of a more federal model put a brake on this ambitious European project; however, the Congress of the Hague created the impetus necessary for the signing of the Treaty of London which, on 5 May 1949, brought into being the Council of Europe, to be based in Strasbourg. This was the final step in the creation of an intergovernmental Europe, reduced in essence to the western countries, and articulated around France and Britain. Inside this structure, economic co-operation would take place within the framework of the OEEC and political cooperation in the Council of Europe based on shared values and human rights, and security would be provided by NATO. Why, then, was there a need for Schuman Declaration a year after the creation of the Council of Europe? And, in the end, was it a success?

Winston Churchill and Robert Schuman visiting Metz on July 14, 1946.

Photographer: |

Aircraft used by the Allies to transport coal to Berlin during the Soviet blockade from 24 June 1948 to 12 May 1949

Photographer: unknown |

The Schuman Plan was, first and foremost, a response to a particular context. From the creation of the Council of Europe to the declaration of 9 May, the Cold War had indeed gained considerably in intensity. The proclamation of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949, the independence movements on the Asian continent and the situation in Korea all bore witness to the spread of communism on a planetary scale. The Cold War had now spread to Germany, as the two German states competed with each to be the embodiment of the nation: the Federal Republic was established on 8 May, 1949, and the Democratic Republic on 7 October of the same year, and the democratic, liberal Germany of the West now faced the Soviet Germany of the East. For the United States, integrating this West Germany into the structures of the free world, and thus turning the old enemy into a partner, was an absolute priority; facing the bloc dominated by Stalin, unity among the democratic nations was of paramount importance. This meant that there was a need to change the traditional policy towards Germany – above all, the policy of the French towards its old foe. However, the first declarations of the Adenauer government, questioning the status of the Saar and the International Authority of the Ruhr, did little to calm the Federal Republic’s neighbours. Paris, like its allies, had made the containment of Germany the cornerstone of its foreign policy. How could these conflicting national interests, which so risked weakening the West, be reconciled? The West (with the exception of the United States) also faced the task of its material reconstruction. This reconstruction had to be successful if the liberal European states were to avoid social unrest and disenchantment that would play into the hands of the communist movements and the USSR. Bottlenecks were emerging: a lack of iron for the young West Germany, a shortage of coal and coke for France. The same problems were noted in the Benelux states, Italy, and the UK. The competition for energy and useful raw materials might easily rekindle the national demands that had caused such damage in previous decades. So the international situation, the need to rebuild Europe inside a Western framework in a way that also satisfied national interests required an innovative, original response capable of overcoming these challenges. This response was the Schuman Plan.

By proposing to Germany – and to those who were keen to join this first Franco-German accord – that coal and steel should be placed under a common authority, Robert Schuman applied a long-term vision to an ongoing emergency. His proposals provided immediate solutions to the problems of the moment: the pooling of resources necessary for the economic reconstruction of Western Europe; the integration of federal Germany into the European model, thus consolidating the bloc of free nations facing the USSR; and the immediate satisfaction of national interests, allowing the recognition of Germany and the security of France. But at the same time it opened up new perspectives for the future: it traced the outlines and constituted the first steps of a supranational Europe, including this Europe in a process of pacification (indeed, the word “peace” appears on many occasions in the declaration). The project was an open one – a project for hope. Finally, Schuman did not forget the wider world: he was particularly concerned with Africa, towards which, in his view, Europe held a special responsibility.

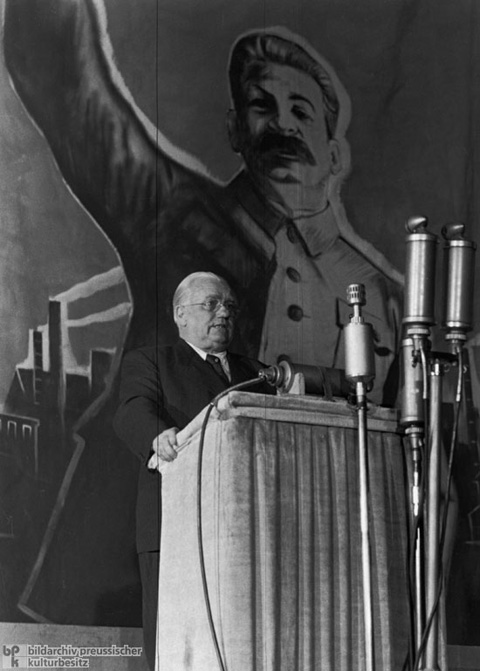

Konrad Adenauer after receiving the occupation statute on September 21, 1949.

Photographer: unknown | © Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Source: Fondation Jean Monnet pour l’Europe et Centre de recherches européennes, Lausanne | CVCE.eu

By renouncing their sovereignty over coal and steel, the states accepted the principle of a higher interest than their own national interests and allowed a supranational decision-making framework to replace their domestic systems. The six participants in the Schuman plan were thus able to strengthen the economic links they maintained through the OEEC by creating an outline of a more integrated set of economies with a common framework for energy and heavy industry, which would also have an impact on their processing industries. However, the Schuman project went far beyond economic matters. In the aftermath of a deadly war, the French Foreign Minister had placed reconciliation (primarily, Franco-German reconciliation) at the very heart of his plan. This spirit of reconciliation was intended to encourage other countries to join France and Germany inside this virtuous spiral, which would allow the FRG to come closer to its neighbours and would also bring Italy, tainted as well by its recent Fascist past, back to the European table. At the same time, this reconciliation guaranteed security for the old states who had suffered the aggressions of the former Axis powers, and thus reinforced the bloc’s solidity. The process was open to all countries keen to share its perspective. To those in the west first: Germany, which immediately responded favourably, was followed by the Benelux countries and then Italy. There were hopes that the UK would join, but London did not want a supranational union. Nevertheless, the door remained open and the negotiations for the Treaty of Rome in its initial phase, the Spaak Committee, showed that the Six were ready to find room for the British should they change their minds. The Schuman Plan was also a symbol for the states of central and eastern Europe which were undergoing forced integration in the Soviet bloc in a process far removed from this model of voluntary and free association. Finally, this first community felt a particular responsibility towards Africa and undertook to aid its development at a time when the decolonization process had taken off in Asia and when Africans were beginning to stake their claim to the management of their destiny.

Photographer: |

The Schuman Plan outlined the prospect of a supranational, reconciled Europe, an agent for economic development and peace. But it did not just draw the first sketches of the project; it set out a method of construction. The Schuman Declaration advocated the functionalism dear to Jean Monnet, who had inspired the project of the High Authority for Coal and Steel. It was through economic integration, and through small steps, that this political and federal Europe would be achieved. The economy made it possible to create the spill-over effect that Schuman regarded as essential to the progress of the community. The pooling of coal and steel ushered in the institutions that shaped the community brand: a two-headed executive with a supranational structure on the one side and on the other a council representing the states, a parliamentary assembly, a court of justice and a body representing social partners (the Advisory Committee, later the Economic and Social Council). This method, in which progressive and prudent construction never lost sight of its final objective of a political and federal Europe, put its faith in the convergence of national interests over time through the application of common policies. Coal and steel policy was the first; this “revolutionary” project, to quote the French daily Le Monde after the declaration of 9 May, 1950, was the cornerstone of the project that would lead to the construction of the European Union.

For all the obstacles it has had to face, the construction of the European Community owes a great deal to Schuman’s initiative. Once the vision and the method of the declaration were in place, the process could begin. The Treaties of Rome also pushed forward this plan, which saw the economy as the basis of a political perspective and a project for a supranational Europe. The progress of the Community was also based on a Franco-German agreement sealed at the time of the Spaak committee and in the context of the Trente Glorieuses, the 30 years of expansion in post-war France, and the economic miracles in other western countries. Closer to our times, the Single European Act, “Jacques Delors’ favourite treaty”, followed the same path: a long-term vision of further European integration served by functionalism and based on the economy, via the creation of the single market. But the Single Act was also a response to a particular context, that of emerging globalization; the creation of the single market provided Europe with an instrument to take on the challenges posed by the new global situation. This project strengthened the power of the Community and enabled it to play its part in the evolution of East-West relations, and in particular to reach out to an Eastern Europe ready for change.

Arguably, the Monnet-Schuman method reached its apogee in the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. The course was clearly marked out: the European Union, created for this end, is federal in nature with powers embodied in its three pillars and with a principle of subsidiarity which leaves the other fields of politics to the member states. Once again, Maastricht was a response to a context: the geopolitical context, insofar as the Union was created as a political power at a time of uncertainty after the end of the Cold War and at a time of reflection on a new international order, and also the economic context, insofar as the European Monetary Union allowed the EU to compete with the great economic powers already established such as the US and Japan, and those emerging at the time such as China.

European Defence Community Treaty Signed in Paris on May 27, 1952

Photographer: |

But history also highlights the difficulties of moving forward when the elements laid out in the Schuman Plan are absent. The European Defence Community (EDC) is an illustration of this. Created by a 1952 treaty, the EDC was immediately rendered obsolete by the end of the Korean War and the death of Stalin. The result of the Geneva Conference, which seemed to settle the problems of European involvement in Asia, suggested that this defence force was no longer required and could be simply subsumed within the framework of NATO. France rejected the EDC project because it clashed with French interests, and other stand-offs led to similar conclusions. The empty chair crisis in 1965/1966 taught a dual lesson: the Community cannot build something against the wishes of a member state; but at the same time a members state cannot impose its own project on the Community (see the failure of the Fouchet plans). The text of the Luxembourg compromise, which freed the Community from deadlock, reflects this situation. The European crisis of the early 1980s highlighted this lesson once again.

Today, we may wonder about the relationship between the Schuman Declaration and the last two or three decades of the construction of Europe. From Maastricht via Amsterdam to Lisbon, the Union has widened to such an extent that it now covers almost the whole of Europe. But the atmosphere of restiveness among some member states is palpable; and at the same time other states are dragging their feet. Between the laborious ratification of the Maastricht Treaty and the failed project of the European constitution, the citizens of four states have expressed their doubts about the European project on three occasions: the Danes in 1992, the Irish in 2001 and the French and Dutch in 2005. Finally, in 2016, a majority of British citizens voted to leave the EU.

“If the European project

is to succeed, it must now

convince Europeans

of its value.“

If the European project is to succeed, it must now convince Europeans of its value. The debt crisis, the refugee crisis and the current health crisis show that there is still a long way to go. Did Schuman have public opinion behind him when he launched his CECA project? It is hard to say. Certainly there was opposition to the project, from the communists and Gaullists in France, from the SPD of Kurt Schumacher in Germany, and from the communists in Italy. Other currents supported him: the Christian Democrats, some socialists, and reformist trade unions in particular. Overall, large majorities in each of the states contributed to this “permissive consensus” in favour of the construction of Europe – a consensus so characteristic of the Cold War years. However, even during that period there were certain dissenting voices: voters in Norway rejected their country’s proposed entry into the EEC in 1972; and when the French were consulted in the spring of 1972 regarding the first enlargement, 40 % of the electorate abstained. Since the very first elections to the European Parliament in 1979, abstention rates have always been higher than in national elections. What is more, the end of the bipolar world order put an end to this permissive consensus. Recovering people’s faith in the European project has been the great challenge facing the Union since the end of the last century. For Europe to succeed, it must meet people’s expectations in the areas of economics, politics, and health. Be that as it may, in the post-war years these expectations were met by NATO, by the strong growth of the Trente Glorieuses in France, and the solidarity necessary during the Cold War, and it was the Schuman Declaration that set them in motion.

“Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity.”

Key quote of the Schuman Declaration. The full text is available here.

A brief history of the

Schuman-Monnet tandem

Philippe Le Guen,

Outreach coordinator of the

Maison Jean Monnet for the European Parliament

At their meeting in the quiet garden of Monnet’s cottage outside Paris in spring 1950, Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman decided to draft what would later become the founding text of the first European Community. Before this, the two men, who were quite different in terms of personality and background, had not been friends and had the opportunity to work together.

“There will be no peace in Europe, if the states are reconstituted on the basis of national sovereignty… The countries of Europe are too small to guarantee their peoples the necessary prosperity and social development. The European states must constitute themselves into a federation…”

Bernard Clappier, Robert Schuman and Jean Monnet (Houjarray, 1950)

Photographer: |

Jean Monnet, born in 1888 to a family of brandy-merchants, was above all a talented salesman. By one of the fortunes of history, in his twenties he had left the family business and from then on devoted his entire life to public affairs. He played many important roles throughout the course of the twentieth century, notably improving the economic cooperation to provide war resources between the Allies in the first world war, becoming one of the masterminds of the freshly created League of Nations in the interwar years, and playing a key part in coordinating Allied war resources during the second war. He was also central to the creation of the US Victory Program.

Robert Schuman, two years younger than Monnet, was a Luxembourg-born statesman who spent his childhood in Alsace-Lorraine, which had been annexed by Germany in 1871 and only returned to France after the Great War. In 1919 Schuman, who had graduated as a lawyer in the then German University of Strasbourg, became active in French politics and was very soon elected as a member of parliament in Paris. A strong supporter of Catholic movements, he rapidly gained influence in the French political scene and in 1940 was appointed a minister of France’s wartime government. Later arrested and imprisoned by the Nazis, he managed to escape and became a fugitive sheltering in monasteries until the country’s liberation. After the war, Schuman came to prominence under the patronage of General de Gaulle, serving as prime minister from 1947 until 1948 and proposing the creation of a first European Assembly, known as the Council of Europe. For the first time in history, its founding states agreed to define the frontiers of a Europe based on the principles of human rights and fundamental freedoms that Schuman had laid down.

In 1950, Schuman became French foreign minister and dedicated himself to strengthening European reconciliation under the auspices of the Council of Europe, which had recently adopted the European Convention for Human Rights. However, Schuman wanted to go further, seeking a way to foster the common interests between European countries which would gradually lead to a greater political integration. Then came his decisive encounter with Jean Monnet, who at the time was leading the national planning commission for the modernization of France and who, as early as 1943, had declared: “There will be no peace in Europe, if the states are reconstituted on the basis of national sovereignty… The countries of Europe are too small to guarantee their peoples the necessary prosperity and social development. The European states must constitute themselves into a federation…” These revolutionary ideas coincided with Schuman’s own vision for the future of the European bloc.

The daring plan that Monnet proposed to Schuman while savouring the famous family cognac on comfortable lounge chairs in his cottage garden was a welcome surprise for the foreign minister. In Monnet’s radical thinking, Schuman immediately saw the way to avoid the mistakes of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. The cornerstone of the plan was the achievement of reconciliation and peace between the “hereditary enemies” in Western Europe, while creating an economic union between the members of the new “European community of coal and steel”, which also had a long-term political purpose in anticipation of a possible European federation. Schuman was immediately enthusiastic, though somewhat taken aback by the boldness of this project. Notwithstanding, Monnet had long prepared his answers to all possible objections: he already had put the details of his extremely audacious scheme in place, and was just awaiting the arrival of a politician brave enough to endorse the venture.

Photographer: unknown |

Centre européen Robert-Schuman

Both these visionary men agreed that the project should be publicly announced without delay and that it would be Schuman’s duty, as one of the most respected politicians in France and in Europe, to make the official declaration as representative of the French government. Monnet and his team would be in charge of drafting the statement. This task began in Monnet’s house in the village of Houjarray during the last days of April and in early May 1950. It took nine days, nine draft versions, and countless hours of work before the small group of experts under Monnet were able to agree on the precise wording of the text. On the morning of Saturday 6 May, Monnet wrote in blue ink on the front page of the ninth version: “final, to be sent to Schuman”. A courier was immediately dispatched to Schuman’s home in Scy-Chazelles near Metz where the foreign minister was spending the weekend and was eagerly awaiting the result of Monnet’s work. The text did not disappoint and he telephoned Monnet the next morning to say that he would read it aloud at the press conference scheduled at the Quai d’Orsay Salon de l’Horloge on Tuesday 9 May. The die had been cast.

How the story continued is well known. The Declaration that was proclaimed in soft tones by the minister on that day, with Jean Monnet sitting impassively beside him, took the audience of journalists completely by surprise: the newspaper headlines on the next day spoke of the “Schuman Bomb” and “A giant leap in the unknown”. The first European Community was born. Schuman and Monnet continued to work together until Schuman’s death in September 1963; his grave is in a chapel standing outside his house in Scy-Chazelles, which today is a museum managed by the regional council.

In 1975, at the age of 87, Monnet decided to quit all his public activities and to retire to his country house to write his memoirs. In 1976 he was awarded the title of the first “Honorary Citizen of Europe” by all the European heads of state and governments. He died in March 1979 and now rests in the Panthéon in Paris. Jean Monnet’s house was purchased by the European Parliament in 1982, and is now a museum and education centre.

May 9 has become the Day of Europe.

Life Chronology

Direction

Jordi Guixé

Concept

Fernanda Zanuzzi

Ricard Conesa

Translation

Linguistic Services of the University of Barcelona

Coordination

Oriol López

Visual research

Fernanda Zanuzzi

Web design

Carles Mestre

Images & Archives

Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris

British Movietone – AP Archives

British Pathé

Bundesarchiv

CVCE.eu

Council of Europe Historical Archives

Europeana Collection

German History in Documents and Images (GHDI)

Historical Archives of the European Union

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Multimedia Centre of the European Parliament

Nationaal Archief

NATO

US National Archives

Aknowledgments

Jean Monnet House | European Parliament

Office of the European Parliament in Barcelona

Multimedia Centre of the European Parliament