Columbia University student and EUROM fellow (2017)

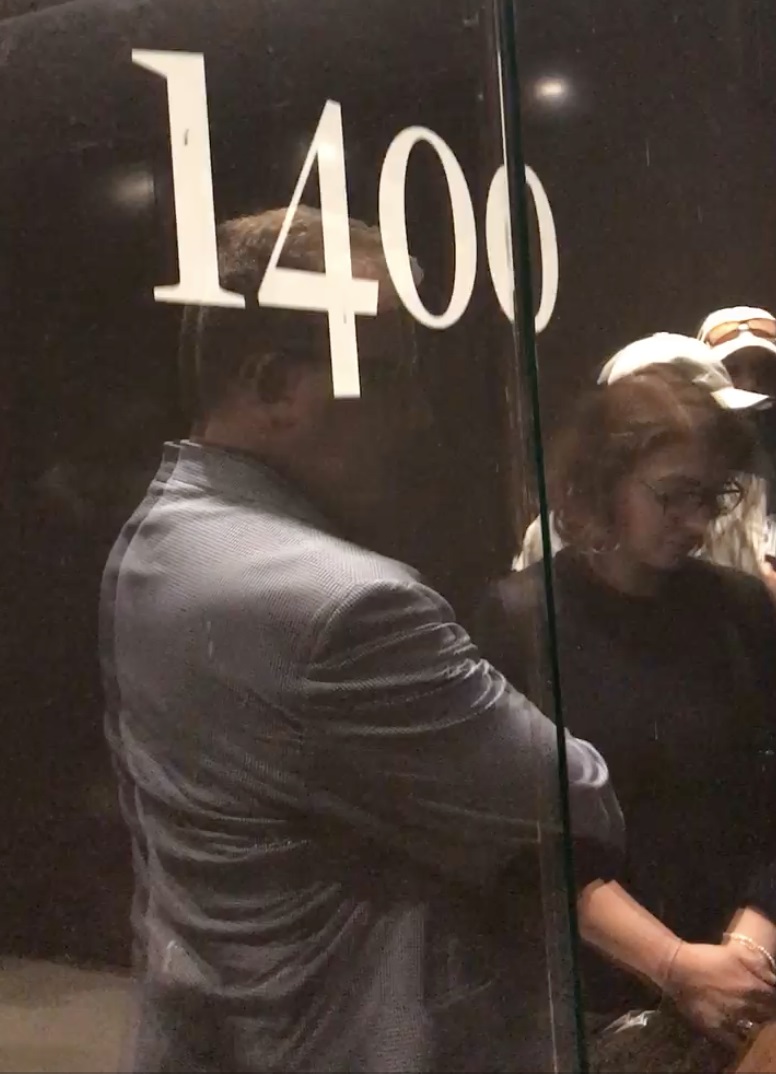

Cover picture: A statue of Thomas Jefferson hovers over the illuminated phrase, while a black figure hovers in the background.

The arduous struggle throughout history between the legal recognition of equal rights for African Americans and the actual implementation of these rights ironically resembles the timeline of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, otherwise known as NMAAH. Since 1915, the United States government has suggested the need for a educational center specifically dedicated to the experience of African Americans. From then on, government advocates have mobilized legislation for the museum but have faced a series of barriers preventing its ultimate commission. In the face of these barriers, black activists have seen the delay of the museum as a delegitimization of black history and culture— an affront to the distinct historical and contemporary realities faced by African Americans, and an aversion towards investing in the memorialization of an undivulged history.

This drawn out history behind the making of the museum highlights the monumentality of its successful commissioning in 2001 and opening in September of 2016, and explains why visitors are invited into the museum’s own history before they are instructed to enter an elevator in order to drop down about 600 years in African-American history to the 15th century. In this vein, the visitors gradually make their way from the basement that begins the story with the Atlantic Slave Trade to the highest levels that celebrate black culture.

Herein lies a key design component of the museum— verticality— that informs the content as well as the visitor experience. Though verticality dictates the chronological display of African-American history by instructing visitors to walk forward through history, the museum insists that “progress” cannot be understood through the same vertical means. Progress is rather a churning of cycles; for every two steps forward there will always be at least one step back.

This complication of progress can be understood when contextualizing African-American history within the inception of a constitutional America. After the visitors pass through the claustrophobic and low-ceilinged exhibition area of pre-constitutional America, which displays the history of the Atlantic Slave Trade– from the capture of African peoples illustrated through the display of small shackles used on children, to the commercialization as well as the racialization of slavery illustrated through legal documents– they then walk into a drastically different space. The ceilings are suddenly raised at least five stories higher and there is more space to walk around.

In my personal experience, I rejoiced at this point of the exhibit. I felt as though a weight had been lifted off my shoulders, one not just informed by the confinement of space but also by the harsh and unforgiving realities of my country’s history, those made especially tangible by the museography resources. But the opening of space does not actually lift the metaphorical weight; immediately visitors are drawn back into the complication of the nation’s founding, one that posits a “paradox of liberty.” This phrase illuminates the grand hall where Thomas Jefferson’s statue is contrasted by a pyramid pile of over one hundred bricks, which each contain the name of a slave that he owned. That the seminal Founding Father of the United States owned people while heralding in the first free nation in modern human existence elucidates the contradiction of the declaration that “all men are created equal.”

Therefore, throughout the rest of the historical section, the museum conveys that the great titans in African-American history were those who navigated ways of broadening the scope of equality, and most importantly, broadening the path for others to follow their lead. In accordance with this concept, the museum design invites visitors to walk around the Jefferson statue in order to achieve a new point of view: one that includes a multitude of other bronze statues memorializing black heroes, like Phillis Wheatley, the first published African-American woman poet, and Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of the Haitian Revolution.

This restructuring of perspective is necessitated throughout the visitors’ elevation into the historical periods of the Reconstruction and civil-rights movement in order to set the stage for the museum’s seminal takeaway, that “African American history is the quintessential American history, [one] of making a way out of no way, of mustering the nimbleness, ingenuity and perseverance to establish a place in this society.” Perseverance, above all, is tested in the average visitor; just as the visitor must physically muster the energy to walk through time, they must also process so much content spreading almost 400,000 square feet that the museum actually advises that the entirety of the complex be explored in multiple visits.

Because beyond the historical section of the museum the visitor is elevated into uplifting exhibit areas that vibrantly celebrate black culture: the byproduct of customs, art, sports, and intellectual achievement developing in conversation with African American history. The museum insists that black culture must be understood as a materialization of black experience, and above all, the essential means of “establishing a place in this society.” Muhammed Ali’s boxing headgear, Louis Armstrong’s trumpet, James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time,” Oprah Winfrey’s audience chairs, and a gown from First Lady Michelle Obama’s fashion repertoire represent just a sample of the museum’s collection that serve as timeless symbols, which help articulate black experience and simultaneously inform a great bulk of American culture.

Perhaps the most humbling point of the visit is the departure from the building. Visitors walk out of the bronze building, a dense hub of information and artifacts, to find themselves at the cross section of two white structures: the Washington Monument and the National Museum of American History. And the reciprocity between all three structures is clear as day; without the slaves, there would be no labor to build memorials like the Monument, and without black soldiers, there would be no Republic to celebrate. So though American citizens inherit a troubled history, the NMAAHC testifies that we must constantly revisit histories, to shift perspectives and modes of thinking, and above all, uncover truths to help navigate paths towards solidarity. The waiting lines that boast hundreds of visitors since the museum’s opening only show promising signs.